The surprise isn’t that Adam Bork was voted into the Grizzly Sports Hall of Fame and will be formally inducted into that elite club later this month.

After all, the guy placed 10th in the decathlon as a junior at the 2001 NCAA Track and Field Championships in Eugene, Ore., then bettered that with a sixth-place showing in Baton Rouge, La., a year later.

He was a two-time all-American in the two-day, 10-event suffer-fest that gives the Olympic champion the title World’s Greatest Athlete. And there aren’t many epitaphs much cooler than that.

A two-time all-American in something that requires speed, hops, endurance and strength, plus enough courage to attack the pole vault eight events in and the fortitude to face the 1,500 meters in the final event, when all you want to be is done and sitting in the shade somewhere with a cool drink in your hand, the pressure finally released.

It takes a hardiness of spirit to compete in the decathlon, to compete for hours on end for two consecutive days, to bring it in the moments that require you to be at your very best. Bork had it, deep reserves of it.

No, what’s surprising is how he got there.

Consider: as a junior at Bigfork High, he went 13 feet, six inches in his specialty, the pole vault. “I remember thinking at the time, man, I’m getting pretty good,” he says. He tried some other events, but “I wasn’t good enough to be competitive in those.”

Years later, when he would become a coach of all-Americans himself at Montana, he says he wouldn’t have even given a 13-6 pole vaulter in his junior year a second look. “That’s not very good.”

But he stuck with it and improved to 15-1 as a senior, which earned him an on-campus visit at Montana, but only after his mom had contacted then coach Tom Raunig and convinced him to at least talk to her son.

After all, he had been the 1997 Class A pole vault champion for the state of Montana!

Are there other Grizzly Sports Hall of Famers who ended their senior years not knowing if they would be competing in their sport at the collegiate level? That had to initiate the recruiting process? There is now.

He traveled to Missoula for a one-day official visit that summer and was hosted by Troy McDonough, and could there have been anything more overwhelming for a kid from Bigfork?

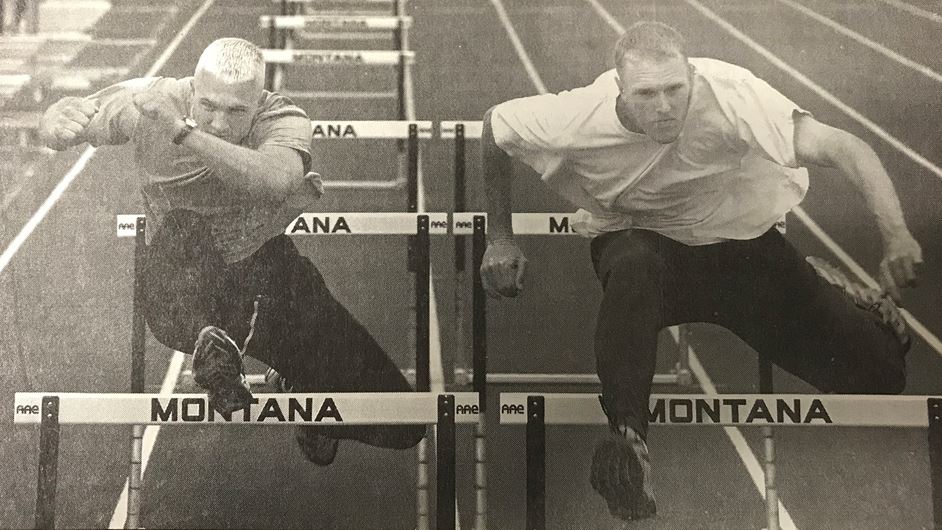

McDonough was a beast of a man — part Adonis, part Hercules — who would go on to place fourth in the decathlon at the 1999 NCAA Championships and had on his arm that day the beautiful Andrea Grove, his future wife. Bork was a pole vaulter, one who was undersized for his class.

“It was definitely a shock coming from a small town. Troy was a lot bigger athlete than I was used to seeing. I was out of my comfort zone for sure. I was shy and quiet. It was intimidating,” Bork says.

Five years later, on May 29, 2002, Bork would be in Baton Rouge, getting into the blocks for the first of the decathlon’s 10 events at the NCAA Championships.

As he got onto his hands and knees, he did so fearing no other man on the track that day, no matter their build, no matter the name of the school on their uniform.

And that’s what is surprising. Not that Bork is soon to be inducted into the Grizzly Sports Hall of Fame, but the transformation he went through, of the one-event kid from Bigfork becoming the multi-event athlete at Montana who could go to nationals and feel not just that he belonged but that he could win the whole thing.

“He never said it, but he wanted to be really, really good,” said his coach, Brian Schweyen. “He envisioned himself being as good as anybody, even the best, so he had that mental edge that is kind of the separator.

“He was never overwhelmed, never afraid of the competition. He just had a great head on his shoulders and knew what he wanted to achieve.”

He was born in Minnesota, into an extended family of wrestlers, and moved to Montana when he was four.

He didn’t follow his heart into wrestling and the pole vault as much as he followed in the footsteps of his older brother, Aaron.

“I tried to do the sports he was interested in, as younger brothers tend to do,” Bork says. “I just tried to follow him, compete with him and try to outdo him. I just kind of followed his lead on most of the sports.”

He would finish fourth at the Class B-C state wrestling tournament as a freshman in 1994 in the … wait for it … 98-pound weight division. As a senior in 1997, he was sixth at 160 pounds.

But that was ground-based stuff. It wasn’t until he tried the pole vault in his first year on the Bigfork track and field team that he learned he could fly.

He liked the challenge of trying to master a fiberglass pole, of trusting technique and coaching when physics would have told him he was crazy.

Even more he couldn’t get enough of the thrill, of cheating gravity. “I still remember the initial feeling of right when I learned how to bend a pole for the first time. It’s a pretty cool feeling to be in the air and feel that bend release and throw you upward,” he says.

“I really enjoyed that from the beginning. Then the better you get, the more of that feeling you get. It was an adrenaline rush.”

His was a small world, with Bigfork and family — mom, dad, four kids, two boys, two girls — at the center, and bus trips to other nearby towns for sporting events about all he needed to be living his best life.

“I was pretty clueless in high school. Even going into my senior year, I didn’t know the difference between Montana and Montana State. I didn’t know which one was in which city. I didn’t follow college sports at all,” he says.

“I didn’t think I would be good enough to compete at the college level, so it wasn’t a dream I had. Some people say they wanted to be a Griz since they were little. That wasn’t me.”

He arrived in Missoula in the fall of 1997, as did another kid from northwest Montana, Bryan Anderson, out of Whitefish. And after splitting a coaching position prior to that, Schweyen that fall became a full-time assistant under Raunig.

It was the perfect storm, a convergence of energy, talent and potential, with McDonough leading the way, Schweyen coaching and Bork and Anderson getting caught up in it all.

They would start a multi-events dynasty at Montana, with McDonough placing fourth at nationals in 1999 with 7,454 points and Bork posting back-to-back all-America finishes, with 7,299 points in 2001 and a then school-record 7,699 in 2002.

Andrew Levin would follow, maybe the best of them all. He won the 2005 Big Sky decathlon title with a meet- and school-record 7,801 points, which gave him a nearly 1,000-point buffer between him and second place. A decathlon domination.

He would go on to nationals in Sacramento and lead the decathlon after Day 1 before ultimately placing sixth, giving Montana four all-America finishes in seven years.

And that does not include Anderson, who placed 10th in 2002 to Bork’s sixth and would go on to compete in the U.S. Olympic Trials two years later.

“There was a ton of pride in what we were able to accomplish. We took pride in coming from a small school and competing with everybody nationally,” says Anderson, now a financial advisor in the Flathead.

“We felt like we were setting up a legacy, and in a lot of ways we did. Troy was the beginning of it, Adam and I came after that and there has been a long string of pretty successful decathletes at the University of Montana.”

With Schweyen still doing the coaching, Austin Emry became a two-time, second-team all-American in the heptathlon at NCAA indoor championship meets in 2013 and ’14. Lindsey Hall would finish seventh in the heptathlon at the 2014 NCAA outdoor championships to add to Montana’s all-America legacy.

“Troy really did start it off. Probably the only reason I ever did decathlon was because Troy convinced me to do it,” says Anderson, who began training for the multi-events as a freshman.

“Troy is the guy who made us believe it was possible. He really pulled us along at the beginning. We were lucky to have that.”

Bork stuck with the pole vault through his first year, then tugged on Schweyen’s sleeve one day and said he, too, wanted to join the group.

“I felt like I was a good enough athlete and I was continuing to grow. I was young for my class, so I continued to put on another 20 pounds and mature even more my freshman year,” says Bork.

He didn’t necessarily have the decathlon in mind, but he was ready to break out of the pole vault-only box he was in.

“I thought it would be fun to try some other events. I picked up a couple of them well enough for Brian to see it would be worth putting a little bit more time into me,” Bork says.

If McDonough at the time was The Man, Anderson, who got a one-year head start on Bork in training for the multi-events, was The Second Coming. Bork, when he was a sophomore, just tried not to fall behind.

“I was just trying to keep up with Brian and Troy. They were some incredible training partners. I had to play catch-up in learning most of the events, then I tried to be as competitive as them and compete against them as teammates. That’s what you do to make each other better,” says Bork.

It was a modest start for Bork, whose very first decathlon, at the 1999 Big Sky outdoor championships as a sophomore, resulted in a score of 6,754 and a fourth-place finish.

He came in more than 200 points behind Anderson, more than 700 points behind the winner, Montana State’s Steve Keller, whose two-day total of 7,477 must have looked like Everest to Bork. How could a guy ever reach those heights?

All it would take was time, talent and a willingness put in the effort to, if not master 10 events, then at least become as good as possible at them.

Bork’s secret weapon: the pole vault, which is a weak link for most decathletes.

“He had that one big thing. He was a really good pole vaulter,” says Anderson, who came to Montana as a hurdler and jumper before expanding his repertoire.

“He kind of hit the ground running with that. And he had the speed and all the tools he needed. He started (competing in the decathlon) a year after I did, but he had everything he needed to do it.”

Bork redshirted the 2000 indoor season, then was forced to sit out outdoors as well with an injury.

This is a good spot for an aside, to describe an analogy that Schweyen, who stepped down from coaching in August 2020, came up with in his years and years in the sport.

He says it like this: that an athlete has to pick out the kind of house they want. Some want the big house on the hill. Some are fine with the smaller house down in the valley.

What they do in their career, the work they put in, the visualization, the attention to diet, rest and recovery, is what goes toward making that home a reality.

Somebody might say they want the big house on the hill but are unwilling to make the sacrifices needed to be great. The interior of the house is a mess because it hasn’t been tended to. The kitchen, the highlight of so many homes, gets built with inferior materials, bottoming out the value.

You get the point. The house is there and might look nice from a distance, but there is nothing to it when you get up close and see the inside. What they said they wanted and what they ultimately got were not even close, talk outdoing the walk.

Then there are those who are fine with the smaller home down the hill, and they go about their career making it immaculate. The woodworking, the countertops, the bathrooms, everywhere you turn it’s a model home. It maxes out everything it ever could be and ever wanted to be. And they’re content.

Bork was one of the rare ones. “He wanted the big one and was willing to put in the time to make it great,” says Schweyen. That year he sat out from competition, 2000, was the year he got to work on the house. Every day was about improving, making things better, nothing else, and the results showed.

His second career decathlon? It came in April 2001 in Pocatello, Idaho. Bork totaled 7,470 points, an unheard-of jump from his debut two years earlier. He was going to nationals in Eugene.

“He was always kind of a quiet, shy guy, but he’s got the inner confidence and belief in himself in everything he did,” says Anderson.

With Bork sitting out the decathlon at the 2001 Big Sky outdoor championships, Anderson won by nearly 300 points. Knee surgery kept Anderson from making a legitimate shot at nationals and joining Bork.

With both coming back as fifth-year seniors in 2002 and with Schweyen at the helm, it was as good as it gets.

“From a competitive standpoint, Brian, Adam and I would play games and compete constantly in everything we did,” says Anderson. “That was a constant theme, and it helped both of us.

“It’s something a lot of programs didn’t have, outside of a couple big schools in the SEC. Nobody else had a world-class training partner. And for it to be two guys from northwest Montana? You just don’t see that very often.”

They got a glimpse of how good they had it on a winter trip to Florida for some warm-weather training before the indoor season began in earnest.

Staying with Anderson’s aunt and uncle in Gainesville, Bork and Anderson made the University of Florida’s track and field complex their home. At the track most days was a solitary figure, a guy training for the same events the Montana decathletes were.

“He was out there by himself. No coach, no training partner, nothing. He said there wasn’t really a coach (for the decathlon). Who do you train with? By myself. I just kind of do everything on my own,” recalls Anderson.

“Adam and Bryan pushed each other and were incredible training partners. I don’t think either one of them could have gotten to where they were without each other,” says Schweyen.

The 2002 NCAA championships would be held at LSU, in the heart of SEC country. The top athletes in the country were there, strutting their best stuff. Most were legit, but not all.

“By then I’d competed against a lot of people from big-name schools. You’d see their athletes and think, wow, that person is going to be amazing, and then they weren’t,” says Bork, who would go on to defeat the top decathlete from Oregon, Kansas State, Missouri, Wisconsin and Texas A&M.

“I had a pretty good level of confidence by then. I believed that I was as good as those other athletes. For me, as meets got bigger, I got better. I’d learned by then to trust in my own abilities rather than be intimidated by people based on who they’re competing for or what they look like.”

He opened the decathlon running a 10.99 in the 100 meters, even after his block slipped, which should have resulted in a restart.

He went 22-10 in the long jump, 41-6 in the shot, 6-3.25 in the high jump and 49.29 in the 400 meters to finish Day 1 in ninth place.

On Day 2, he made up massive ground in the seventh and eighth events. He had the best discus throw of the 15 competitors, at 151-2, then tied for second in the pole vault at 16-6.75.

He closed going 173-9 in the javelin and running a 4:44.94 for the 1,500 meters. He finished in sixth place behind athletes from LSU, Michigan State, Georgia, Tennessee and Rice.

After disappointing marks in the discus and javelin, Anderson, who was in third overall after Day 1, ran a 4:26.98 in the 1,500 meters, a time bettered by only two others. That allowed him to fight his way back up to 10th in the final standings.

Two schools had two decathletes in the top 10: Tennessee and Montana. “We had a run there when we were one of the top two or three schools in the nation as far as decathletes,” says Schweyen.

Anderson believes it was the weather that got to him, which is not unusual for Montana-based athletes heading to the Deep South in late spring. There is just no way to prepare for the heat and humidity.

He just wishes it could have been the opposite, even once, for all the other athletes to have to travel from the Deep South into the Deep Freeze.

“We would have had the upper hand if they’d come to Montana and done a decathlon in January,” Anderson says. “We used to say all the time we were the Rocky’s of the decathlon, training out in the middle of nowhere,” an easy visual for anyone who has watched the fourth installment of the movies.

“We would shovel the track just to do the running we needed to do. It was pretty crazy what we went through.”

Bork and Anderson continued to train together after their collegiate eligibility was up, with an eye on the 2004 Olympic Trials.

They both competed in the heptathlon at the 2004 USA Indoor Track and Field Championships in Boston at the end of February, but an injury that spring to his hamstring, Bork’s Achilles heel, ended his dream.

Anderson would later score 7,769 points at a Trials qualifier in Chula Vista, giving him lifetime bragging rights over Bork’s 7,699, and he would go on to compete in the Trials in Sacramento.

“That was the end of my training and competing,” said Bork of his hamstring injury. “I was still plenty young, but I was broke. I couldn’t afford to train. I needed to start looking for work.”

He had been doing some volunteer coaching at Montana while still training. After his injury, he was brought on in a part-time capacity for two years before becoming a full-time coach in August 2007.

He had the gift that the best coaches possess: the ability to reach individuals, to get them to be at their best, to believe in themselves even when they might not believe in themselves.

In lockstep with Schweyen, they produced one of the Big Sky Conference’s top track and field programs.

“Track and field had been my whole life. I wanted to see how good I could become and how far I could go. That’s why I chose exercise science (as a major), to learn as much as I could about the human body and how to train it,” he says.

“To be able to move into coaching was definitely a dream at that time for me. It’s an enormous challenge because every athlete is wired differently. It takes time to learn the person and how to relate to them and get them to believe in themselves so they can compete when it matters.”

Bork stepped down from his coaching job over the summer, ready to go all in on his other loves: his family and his woodworking. His gain is the sport’s and the school’s loss.

“Adam was not only a great athlete but a great representative of the athletic department and the University of Montana for so long,” said Schweyen. “He gave that program everything he had for a lot of years.”

It’s not lost on Schweyen, Anderson or Bork that a track and field athlete is going into the Grizzly Sports Hall of Fame at the same time as athletes from Montana’s Big Three of football and men’s and women’s basketball.

It gives the induction an extra dash of meaning, of equal standing.

“It means a lot to me to be in that elite group. I’m definitely very honored. I know they don’t put a lot of people (into the Hall of Fame every year), so I was a little shocked, a little surprised, especially as a track and field athlete,” says Bork.

“For them to acknowledge my achievements feels really good. I’m really thankful that they see me at that level. To be in the Hall of Fame is forever. And for that I’m grateful.”