Earl Old Person, the cultural trustee, political leader, natural resource defender, and peacemaker who led the Blackfeet Indian Reservation for more than six decades — longer than any other tribal leader in U.S. history — died Wednesday after an extended battle with cancer. He was 92.

“The Blackfeet People have suffered a huge loss today with the passing of Chief Old Person,” according to a prepared statement from James McNeely, a tribal spokesperson. “A chapter in our history has come to a close. The Blackfeet Tribe offers prayers and support to the family of Earl at this time.”

During the course of his leadership career, Old Person was named president of the National Congress of American Indians, one of the oldest national organizations representing tribal interests, which he led from 1969 to 1971. He earned an honorary doctorate from the University of Montana and, in 1998, was awarded the Jeanette Rankin Civil Liberties Award by the American Civil Liberties Union.

As Blackfeet Chief, Old Person met the British royal family, the Shah of Iran, and every U.S. president from Harry Truman to Barack Obama, with whom he corresponded in an effort to protect the nearby Badger-Two Medicine area in perpetuity, holding energy companies and development pressures at bay while safeguarding a culturally sacred landscape that is home not only to a suite of wildlife species and natural resources, but also to the Blackfeet creation story.

“These ancient lands are among the most revered landscapes in North America and should not be sacrificed, for any price,” Old Person wrote in a 2015 letter to President Obama, urging him to “permanently protect the integrity of our cultural and natural heritage.”

Under his enduring leadership, the Blackfeet constructed a community college, an industrial park, housing developments, tourist facilities, and a community center. Old Person also threw his enthusiastic endorsement behind the Museum of the Plains Indian in Browning and helped build support for the development of a tribal buffalo herd.

Also known by the names “Cold Wind” and “Charging Home,” Old Person was born on April 13, 1929 and grew up near the Starr School, about 10 miles outside of Browning, close to where he lived until his death. Blackfeet became his first language, which he spoke until he entered grade school, at which point he learned English.

In 1936, the Browning High School basketball team won their first trip to the state tournament in Great Falls and Old Person presented Blackfeet songs and dances at half-time.

In 1938, at age 9, he spent six weeks in Cleveland, Ohio and New York City, furnishing Blackfeet song and dance presentations at schools, colleges, and civic organizations. The proceeds were donated to assist in the building of a local church.

In 1947, he was the only Indian Scout selected to attend the 6th World Boy Scout Jamboree held north of Paris, France.

In the late 1940s, he spent summers working on a track gang for the Great Northern Railway so he could afford new clothes for school. In 1952, he was hired at the tribal land department, his first position in what would become an enduring legacy in tribal governance.

It was there he forged relationships with tribal councilors who encouraged him to run for office because of his relationship with elders. In June 1954, voters elected him from a field of 64 candidates. He soon came up through the ranks and became chairman of the nine-person board, a position he held for decades.

In 1957, he attended Eisenhower’s inauguration, and in 1960, he was invited to John F. Kennedy’s inauguration and participated in the parade. In 1959, he worked as an attaché in the state House of Representatives and held the distinction of being the first full-blooded Native American in this capacity.

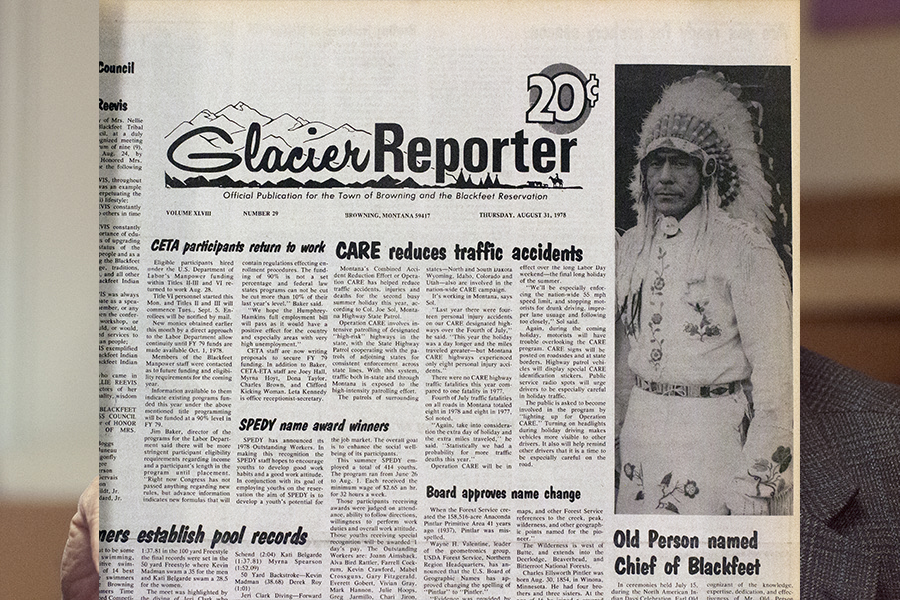

Prior to the 1930s, chiefs traditionally led the Blackfeet Nation. With the death of Chief John Two Guns White Calf in 1934 and the establishment of a council, the position sat vacant for 44 years, until 1978, when Two Guns White Calf’s family bestowed the honorary position upon Old Person.

A champion for civil rights and cultural preservation, he has served as president of the National Congress of American Indians, holds an honorary doctorate from the University of Montana and was awarded the Jeanette Rankin Civil Liberties Award by the American Civil Liberties Union of Montana. In 2007, he was inducted into the Montana Indian Hall of Fame. A dedicated rancher and horseback rider, Old Person was inducted into the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame in 2014.

He was also a proud husband and father, first marrying Virginia Whitegrass, with whom he had one daughter, Earlina, and later marrying Doris Bull Shoe, whose four children from a previous marriage — Alfred, Marty, Glenda, and Rose — joined the family as Old Person’s own. Old Person and Doris, who preceded her husband in death, had one son together, Earl, Jr., and the couple also raised a granddaughter, Twila.

Old Person’s nephew, Terry Tatsey, who is also a former tribal councilman and natural resource studies professor at the Blackfeet Community College in Browning, said Old Person took in so many children through the years, it was often difficult to distinguish his bloodline from his adopted brood.

“In our ways of living, they’re all his children,” Tatsey said, adding that Old Person was such a dedicated tribal steward, performing ceremonies and caring for his people, he often needed help on his ranch. “He was so busy taking care of so many people that my brothers and cousins helped him with his ranching and took care of his race horses. He had to take care of the larger tribal society, so we tried to take care of him.”

Speaking by cell phone, Tatsey and his brother, Keith, were driving to Las Vegas Thursday morning to compete in the Indian National Finals Rodeo, an event that Old Person never missed.

“He attended the first Indian National Finals Rodeo in Salt Lake City in 1976 and never missed it,” Tatsey said. “It’s difficult because we want to be there, but knowing my uncle, he wouldn’t want us to miss this opportunity.”

As a tireless advocate of Blackfeet cultural practices, Old Person impressed the significance of the tribe’s traditions and history on younger generations. He often shared stories of the hardship he endured as a young boy, Tatsey said, including how his own parents woke him each morning with three Blackfeet words that, translated to English, mean: “Good morning! Get up! Try Hard!”

“He grew up just barely surviving, working carnivals and odd jobs to provide extra money for his family, but he always got up and tried hard and that brought him joy,” Tatsey said.

“He’s my uncle and chief and we are very lucky to have him guide us and teach us,” Tatsey said.

As chief and chairman, Old Person regularly traveled to Washington, D.C. to promote the Blackfeet culture, as well as to advocate for retiring oil and gas leases along the Rocky Mountain Front. He met every United States president since Harry Truman and was even invited to Iran in 1971 by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah, to celebrate the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire.

Invited to attend through President Richard Nixon, Old Person described his part in the event to the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center as follows: After arriving in Tehran, he was invited to “high tea” and dressed in his Blackfeet Regalia. Through an interpreter, Old Person was asked to deliver a small talk, inviting the Shah to join him as he stood up. The Shah promptly got to his feet and stood beside Old Person, who noted that nearly the entire audience was smiling, prompting him to consider cutting his speech short. Later, Old Person asked the interpreter if he had said or done something wrong. The interpreter assured him he hadn’t, but crossed a cultural taboo by asking the Shah to rise — as far as the interpreter knew, no one in the previous 2,500 years had asked a Shah to stand.

U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, D-Montana, who worked closely with Old Person and the Blackfeet Nation on multiple fronts, including on efforts to enact legislative measures to furnish permanent protections on the sacred Badger-Two Medicine, expressed his condolences in a prepared statement.

“Chief Old Person was a fierce advocate for the Blackfeet Nation and all of Indian Country for his entire life, and the world is a better place because he was in it,” according to Tester. “He will never be replaced, and we are holding his loved ones and the Blackfeet people in our hearts.”

U.S. Sen. Steve Daines, R-Montana, also issued a statement following news of Old Person’s death.

“I was saddened to hear the news of Chief Earl Old Person passing away. He was a great Montanan and a great American. My prayers are with his family, friends and the entire Blackfeet Nation. It was an honor to know him,” according to the statement.