HELENA – A disruption in the U.S. aluminum supply has put a temporary stop to traditional license plate manufacturing in Montana.

About 750,000 license plates are made each year at the Montana State Prison in the small community of Deer Lodge by inmates working for Montana Correctional Enterprises, a division of the state Department of Corrections. The plate design and numbers are printed on reflective sheets that are applied to pieces of aluminum.

Prison officials notified the Motor Vehicles Division in September that they were running low on aluminum, division administrator Laurie Bakri said Thursday.

Then Montana Correctional Enterprises ran out of aluminum this week, said Carolynn Bright, spokesperson for the Department of Corrections. Another aluminum shipment isn’t expected until early December, officials said.

“We knew this might be a possibility because it’s been an issue at other license plate factories throughout the nation,” MCE Administrator Gayle Butler said in a statement. “To head off the problem, we have been searching for other sources of aluminum non-stop. Unfortunately, everyone is either in the same situation as us, or understandably, they don’t want to find themselves in the same position, so they don’t want to sell their materials.”

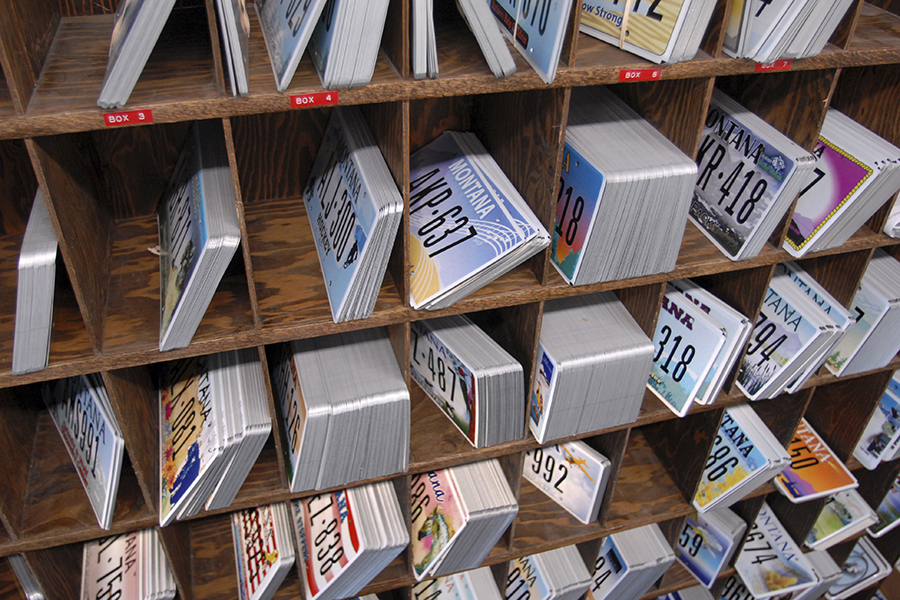

County motor vehicle departments and authorized license plate distribution agents in Missoula and Billings still have some license plates available, Bakri said.

State officials are trying to determine how many aluminum plates are still in stock and whether counties with extra plates can share them with other counties that have dwindling supplies.

“We’re assuming our big counties will run out (of plates) quicker,” Bakri said.

Montana Correctional Enterprises has several plans for temporary plates if counties run out of printed plates, she said.

The division will start by printing plate numbers on the reflective sheets and placing them inside plastic sleeves, similar to the temporary registration license plates that are issued before people get their permanent plates, Bakri said.

“The only difference the consumer will see is the sheeting will not be backed by aluminum,” Butler said. “The bottom line is, MCE will continue to fill orders using this temporary solution until the factory receives the materials necessary to resume normal operations.”

Another option, if the shortage continues, is to apply the reflective sheets onto PVC sheeting to create license plates, Bakri said.

“Hopefully we won’t have to see any of those on cars, but that is our backup plan should aluminum not come in in December,” she said.

People who receive the temporary plates will get permanent plates when regular production resumes, Bakri said.

Other states have had disruptions in printing license plates and some have turned to temporary plates.

In May, North Carolina suspended its program to replace license plates that are more than six years old due to an aluminum shortage.

Arizona had an aluminum supply chain problem that cleared up in June, while Washington state had a license plate shortage in July and August because social distancing requirements for prison workers slowed production, Washington Department of Corrections spokeswoman told The Seattle Times in early August.