50 Years of Girls Basketball

From concrete floors to a 3,000-point scorer, girls hoops have come a long way in Montana in 50 years

By Jeff Welsch; 406mtsports.com

BOZEMAN – Deb Prevost remembers hearing the rumblings about an important high school basketball game involving girls, played 125 miles down the road from her Sidney home in Miles City, and took special note of what they were calling the Glendive team.

State champions.

It was Jan. 20, 1973, and until then Prevost’s exposure to basketball was limited to the after-school Girls Athletic Association program at Sidney and pick-up games with her brother Greg and his buddies on the hoop in the family’s driveway, a decided upgrade from the wire coat hanger they’d bent into a circle and hung on a closet door when first learning the game.

Little did she consider that Glendive’s 43-39 victory over Deer Lodge that day was the historic culmination of a long road toward sanctioning high school girls basketball in Montana after a 64-year hiatus – a milestone marking its 50th anniversary this winter.

“I don’t think I knew any of it was happening until they won,” Prevost recalls of a season that began in October 1972. “And I thought, ‘Wow, how were they able to play?’ I didn’t think much more about it.”

A year later, Prevost’s finale at Sidney, she knew. After a first season in which some 50 teams small and large participated under the Montana High School Association banner, Sidney and another 70 or so schools added girls teams, often under heavy pressure from gender-equity advocates.

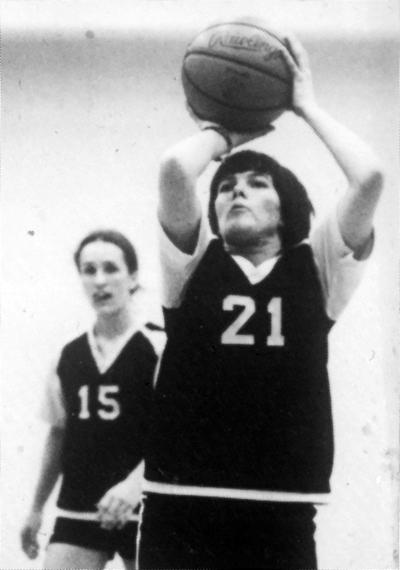

Prevost would become the first in a long line of female Montanans to excel collegiately, as an All-American at Eastern Montana College (now MSU Billings), and then play for money, with the pioneering Women’s Professional Basketball League.

Since those first clumsy games in 1972, when many of the players had little or no experience with basics such as shooting and dribbling — and when facilities and funding and uniforms and coaching knowledge and game scheduling and even the seasons were decidedly unequal — the girls game has evolved to near equality, much of it forced thanks to federal Title IX legislation but most of it earned on the courts.

“I feel like it is (equal),” said Karen Deden, a former Missoula Sentinel standout and longtime Spartans coach who had a Hall of Fame career at the University of Washington before playing professionally. “There’s a lot of things in place in Montana that make it like that. If there isn’t something equitable, we have ways to address it.”

In the 50 years since that first season, Montanans have distinguished themselves.

No fewer than 17 have played professionally. Montanans are in Halls of Fame at Washington, Northwestern, Idaho State, Montana, Montana State and MSU Billings, with Gonzaga surely soon to come.

There’s more: one of the greatest players ever nationally, Denise Curry, a former UCLA All-American and a member of the inaugural Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame class in 1999, learned the game growing up in Fort Benton before her family moved to Davis, California, for high school.

Consider Robin Selvig’s Montana Lady Griz juggernaut, which Sports Illustrated hailed as one of the top 10 all-time for its three decades of dominance beginning in 1980.

Selvig built his teams on the backs of Montana stars over 38 years, many from small towns such as Malta, Fairview, Ovando, Philipsburg, East Glacier, Big Sandy, Box Elder, Polson, Troy and Whitehall. The 1993-94 “Made In Montana” Lady Griz squad that captured the Big Sky Conference regular-season and tournament titles, defeated UNLV in the NCAA Tournament, and put a second-half scare into No. 1 Tennessee, featured 16 players – all Montanans.

“The state of Montana has a lot of really good girls basketball players,” said Deden, whose oldest sister, Linda, played for Sentinel in its inaugural season before another sister, Doris, carried on the tradition. “I think a lot of it is based on work ethic. One of the things I find interesting about Montana players, and what I liked about them, was fundamentals. Obviously there are kids from Montana who are gifted, but they are fundamentally strong all the way around.

“I actually think a lot of people who go to girls basketball games, this is their mindset: They play basketball the way basketball was originally meant to be played.”

Small wonder. When Dr. James Naismith invented the sport in Massachusetts in 1891, girls from coast to coast were the first to queue up.

In Montana, the first organized team comprised largely of high schoolers was a girls squad at Fort Shaw Indian School, in 1897. Seven years later the barnstorming team captured a nation’s fancy, culminating in an unofficial world championship at the St. Louis World’s Fair.

Montana even crowned state champions for a short time until 1908, when after Gallatin County High School took the title girls basketball was no longer supported. Teams continued to play in the shadows statewide for six decades, but the idea was frowned upon as “unladylike” and harmful by the 1950s and ‘60s, and interest sputtered.

And in 1925, Cardwell High claimed an unofficial stte championships after finishing 11-0 and defeating Virginia City twice, Pony twice, Whitehall twice, Boulder twice and Three Forks, Ennis and Logan, which was the closest gamer at 17-14.

“I had an aunt in Minnesota who played,” Prevost recalled, “and her story is that the men decided it was too hard physically on the women, and that’s when the game changed. The men’s game evolved to be bigger, faster, stronger, and the women kind of put an end to it for a while.”

The pendulum began swinging back after the turbulent late 1960s, when the MHSA established girls programs in tennis and golf, then swimming and gymnastics, and later cross country and track.

“There is now a big push of girls’ activities,” MHSA assistant director Les Irish said in 1972 when discussions centered on basketball. “It’s evident in gymnastics and track since 50-60 schools have a program, and they would like to have some control.”

On Jan. 31, 1972, the same year Title IX legislation guaranteed equal opportunity and treatment, the MHSA approved girls basketball by an 85-54 vote. A motion to start with a six-player format – a la Iowa, with four stationary players on each side of mid-court and two “rovers” allowed to go full court – was rejected.

“Girls run the 440 and 880 in track and I don’t see any reason why they can’t run up and down a basketball court,” Ronan’s Joe McDonald argued.

In April, the state was divided into four districts, each to send two teams to the three-day state tournament in Miles City in mid-January. Schools ranging in size from Augusta and Harrison to Great Falls and Kalispell would begin practice in September and play 16 regular-season games in a fall season starting in October.

There would be one class, Irish said, “until the idea of femininity on the basketball court becomes more widespread.”

Opponents raised concerns about funding for coaches, uniforms, travel and tournaments. Others fretted about a caliber of play they expected to be grim, at least initially.

Kalispell Braves coach Joe McKay, who’d guided the boys program before shifting to the girls, noted “I much prefer coaching the girls – they seem to appreciate the help more than the boys.” But he also advised coaches, administrators and spectators to temper expectations, though with a hopeful conclusion.

“Girls have no understanding of basketball terminology,” McKay explained. “So when you talk about a post man or a wing offense you have to explain it 25 different ways so they will understand. Girls have had no exposure to such terms and have had very little practice at handling a basketball. They throw it away a lot. I expect 20-25 turnovers each game, something that would make a boys’ coach tear his hair out.”

“Give the girls four or five years after they have been around the sport and notice the difference. Right now, the girls teams are probably comparable to those of seventh- and eighth-grade boys. But they catch on fast.”

Prevost chuckles at the memory of the sloppiness. Referees repeatedly overlooked violations lest the ball never cross mid-court.

“It was really hard to work on the fundamentals, because they had never done it,” Prevost recalled. “People didn’t have the skills. Girls on our team had never played, except for in the GAA or in P.E.”

Coaches were equally challenged, though many were gratified by the support of male counterparts. At Seeley-Swan, Carolyn Jette had only played basketball in a class at the University of Montana, but legendary boys coach Kim L. Haines, an early proponent of equal opportunity, helped her with defense and offense.

Enthusiasm was high. Of the 60 girls at Seeley-Swan, 30 came out for basketball.

And as McKay prophesized, they learned fast.

“People go to a girls game expecting a real comedy act, and when they get there they are amazed,” Jette said later in the season. “They get very involved. They bring their relatives and neighbors and the crowds grow.

“Women’s sports have always been regarded as inferior, but that is changing.”

Learning the game wasn’t the only hurdle.

The Deer Lodge team, for example, was given $250 for the year and wasn’t allowed to practice in the gym, instead using a large room with a concrete floor. At other schools, girls who could use gyms were scheduled at off times, typically before school or at night.

Many girls teams had to provide their own uniforms. Unlike the boys, whose uniforms were sent to laundry services, the girls had to wash their own.

Prevost remembers being told her team would have to wear their track uniforms. When the MHSA said no to the tops, the school bought jerseys but the team still donned track shorts.

“We had no uniforms, no anything except we did have a school bus,” recalls Diana Pollari, coach of that first Glendive title team. “I can’t even remember how we fed the kids. I remember the day that Bud from Universal Athletics brought his stuff for the uniforms.

“Boy, that was a good day.”

Title IX ushered in change, but in Montana – like the rest of the country — equality came slowly.

In 1982, 10 years after the girls debuted, an 18-year-old all-state player from Missoula Hellgate named Karyn Ridgeway stood up at a public meeting when a moderator asked for volunteers for a lawsuit. Every school in Montana was violating Title IX, her eventual suit alleged, noting that 88% had sports for all seasons for boys to 16% for girls. Ridgeway was joined by athletes at Whitehall and Columbia Falls.

It was one of the country’s first Title IX cases.

“I defined myself in basketball terms and my self-worth depended on it,” Ridgeway, who would later play for the Lady Griz, told UM’s sports information department in 2020. “I loved the pressure. But it was hard not to notice that the boys’ teams were frequently given the better equipment, facilities and schedules.”

Under the so-called Ridgeway Settlement three years later, the MHSA agreed to offer equality in every way, with one notable exception: Fall ball would stay. The suit spurred the addition of volleyball (1983-84) in the winter and softball (1985).

Administrators fought for the fall out of concern for pressure on facilities and difficulty in finding qualified coaches, though one study suggested the root of the dissent was “sexually based attitudes of some of the coaches, athletic directors, administrators and others.”

The seasons issue remained a lightning rod.

Montana was one of only four states playing girls basketball in the fall, which was during the traditional dead season for college recruiters. Coaches had 17 fewer days to evaluate girls than boys.

Some observers even suggest the limited outside exposure in part helped Selvig build his powerhouses.

In 1990, the Deden girls’ mother, Nancy, and friend Bev Henry filed a complaint with the Montana Human Rights Commission challenging the fall season.

“The problem is, as you sit there, you wonder how concerned they (MHSA board) are about football and boys’ basketball, and how little thought goes into women’s sports,” Nancy Deden said then. “It’s almost like it’s an attitude. They make funny remarks about equity. The attitude is starting to change in this state, and the seasons is one of those ways. But Montana was so bad, there’s no way it could get worse. There’s still so much improvement that needs to be done.”

Deden and Henry first noticed disparities when they’d attend Linda Deden’s games at UM, before Selvig was coach.

Most noticeable was the lack of a game program, a staple at men’s games. When they queried UM about it, they were told to pursue their own funding; if they got it, the school would distribute programs.

“Within a day she had funding for it,” Karen Deden remembers.

They formed a booster group for women’s sports at UM called the Copper Connection. They supported a successful Thanksgiving tournament, left goodies in hotel rooms for visiting teams, and of course ensured programs were dispersed.

When Linda was at UM, Doris Deden (now Hasquet) was a freshman at Sentinel. Their mother now saw the same issues she’d noticed at UM.

“I grew up understanding there was this difference,” Karen Deden said.

Ten years and tens of thousands of dollars later, in 2000, the Montana Human Rights Bureau ordered the MHSA to swap girls basketball with volleyball. In 2002, the MHSA did just that.

“When the seasons changed and girls were getting scholarships in other sports and going out of state, it was a good feeling for my mom and my family,” Karen Deden said. “Because it wasn’t easy what she did. My dad jokes now that all those lawsuits and everything they put into it … that was our lake house.

“We don’t have a lake house, obviously,” she added with a laugh.

Deden, who stepped down as Sentinel’s coach last year, ending a 49-year run in which a family member was directly connected to the program as a player or coach, remembers the nasty letters her mom and Henry received. She says she still gets glares at the grocery store.

“It was a long fight,” she said.

In the 50 seasons since Great Falls Central and Fort Benton made history on an October night in 1972, the game has evolved enormously.

Quick growth enabled the girls to be split into two classes after two years and into the current four classes in 1977. In some towns, such as Malta, Fairfield and Belt, the girls programs are not only equal, they’re revered.

A whirling dervish from Brockton named Kayla Lambert scored 66 and 65 points in games on the way to a whopping 3,453 for her career, 800-plus more than the runner-up. A future Gonzaga Hall of Famer from Fairfield named Jill Barta went 104-0 for her career and scored 41 points – including her team’s last 21 – to beat Malta, the state’s pre-eminent program with 10 titles, in double overtime in the 2014 Class B championship game, part of a 120-game winning streak.

Prevost, who was honored in 2018 at the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in Knoxville, Tennessee, as a “trailblazer of the game”, says inequalities remain, though most are nuanced. Most glaring: In many small towns, girls still routinely play before the boys instead of alternating prime time slots.

“I can remember distinctly when I was coaching (at Sidney) and Title IX came in to see if we were in compliance and being a little shocked that they even counted the shower heads,” she said.

Neither Prevost nor Pollari recall thinking about the landmark implications of 1972 immediately. That came years later.

“It was a situation of we were there for the fun, the joy of it, the exercise and for the sport,” said Pollari, who went on to a 23-year career as a counselor at Bozeman High School after 18 in Glendive. “It was just fun to be able to do it. The kids back in that time, some of them had never been out of town even. So it was opportunity. It’s something that hadn’t been done in a long time.

“It’s a trailblazer kind of thing.”

Prevost now looks back in reverence at those who fought the battles. That includes her coach at Sidney, Virginia Dschaak, who pushed the school board hard for girls to play in the second year, when the number of teams doubled to about 120.

“When we were at the induction to the Hall of Fame, and all those WBL people were up there, one of the striking things for me was to think of all the people that I will never know that fought for equality throughout the whole United States so all of us could be up there on that stage,” she said. “I wish these kids now … they don’t know the struggle that went on for women and girls to be able to be in this position to play, to be able to do the same thing guys do and have people making sure there is equality.

“I think it’s taken for granted.”

406mtsports.com executive sports editor Jeff Welsch can be reached at [email protected] or 406-670-3849. Follow him on Twitter at @406sportswelsch