There was likely dancing in the streets of Polson on a Monday night in May 1930.

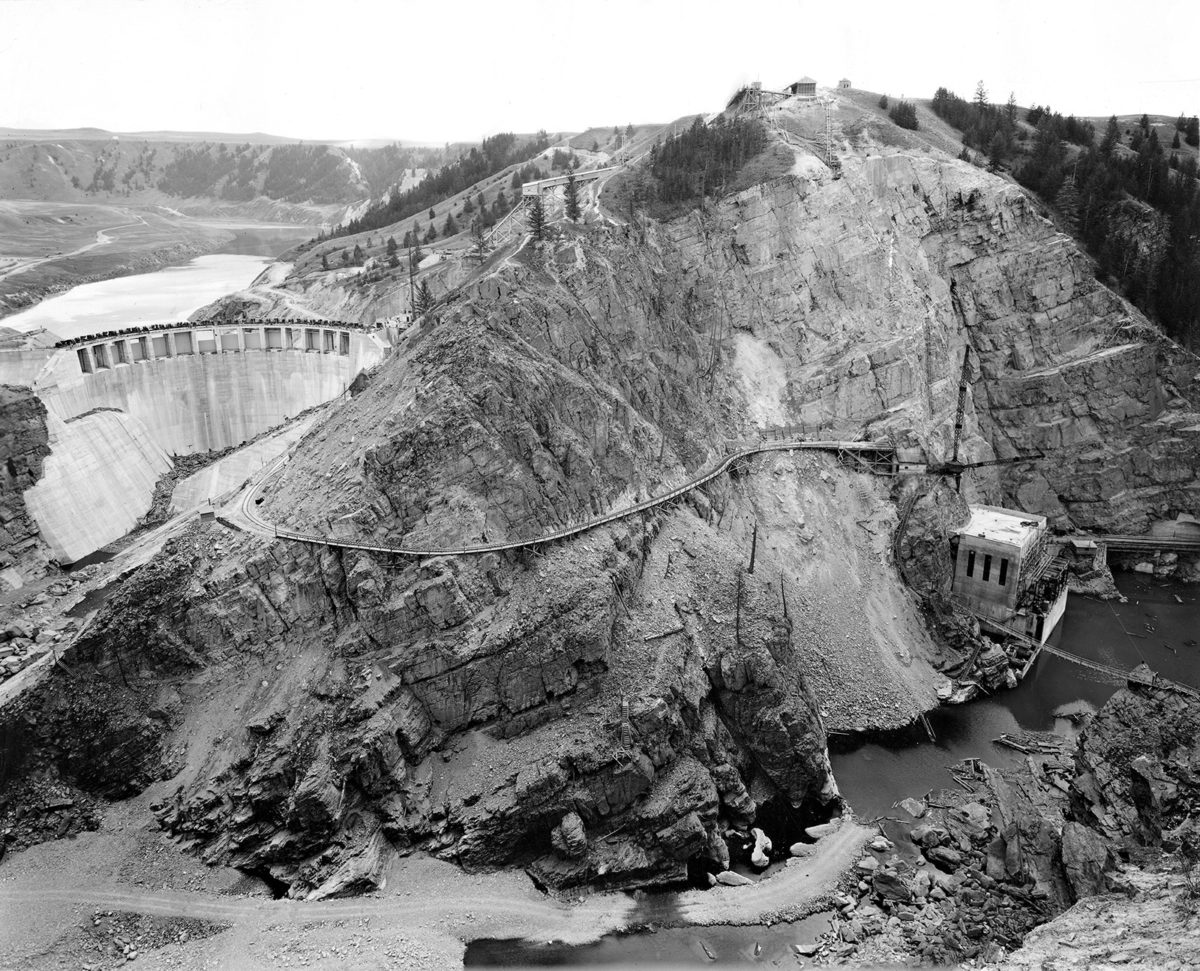

The cause of the frivolity in the little town at the south end of Flathead Lake? A long-awaited, highly contentious decision from a federal agency to grant a 50-year lease to a subsidiary of the Montana Power Company that would allow the construction of a big dam on the Flathead River about six miles southwest of town.

“Polson had its biggest night in history tonight,” began a Missoulian newspaper account, where the lease decision was front-page, banner-headline news. “Every man, woman and child in town joined in the merry making. Bonfires glowed into the night and every kind of noise-making instrument that was available was brought into use…”

The dam project, discussed and debated for more than a decade, was also big news across western Montana, and especially in Butte, the home of Montana Power and its largest customer, the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. The first power line from the dam would run south to Anaconda and Butte to fuel the copper company’s mining and smelting operations.

The lease announcement came about six months after the October 1929 stock-market crash. The clouds of looming depression hung over much of the nation, including Polson and the surrounding Flathead Indian Reservation.

The “Polson dam,” as it was called in the construction days, would bring jobs to many, including CSKT tribal members, and after initial opposition from the power company, annual rental payments to the tribes for use of the site. The rental agreement provided $2.84 million to the tribe over a 20-year period.

But to some native residents, the changes to traditional reservation life and the prospect of a big concrete dam in a narrow canyon where water tumbled fiercely — a place considered sacred by tribal members — was a heavy cost.

The dam project was the latest event in a period of intense change on the reservation that started with the allotment of parcels of tribal land to individual members, the later allowance of ownership of reservation land to non-tribal members, and the development of a large irrigation project intended to promote farming. The overall goal, at least in the eyes of some, was to push native residents into the white world of farming, like it or not.

The big dam project “was part of that assimilation era,” says Brian Lipscomb, the CEO of Energy Keepers Inc., the tribal corporation that now operates the dam, named Selis Ksanka Qlispe (SKQ), for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. “The way of life for tribal people was severely impacted, negatively.”

While there were deep concerns about the project, the tribes at the time lacked the political and economic clout to say no, Lipscomb says.

While the CSKT won the right to buy the dam in 1985 during a federal relicensing process, ownership didn’t come for another 30 years, until 2015. The bitterness over the dam’s development lingered for more than eight decades but the hard feelings were fortified early by a series of tragic events.

Work on the dam began quickly after the lease was signed in 1930. But in the spring of 1931, as the Great Depression deepened, Montana Power pulled the plug on the Polson project. Anaconda operations were suspended, due to falling demand for copper, and without its biggest customer, Montana Power had little incentive to boost its electricity production. But five years later, the company restarted the dam project, bolstered by $5 million from the New Deal’s Public Works Administration. Construction projects — bridges, roads, public buildings and hydroelectric dams — provided jobs and hope.

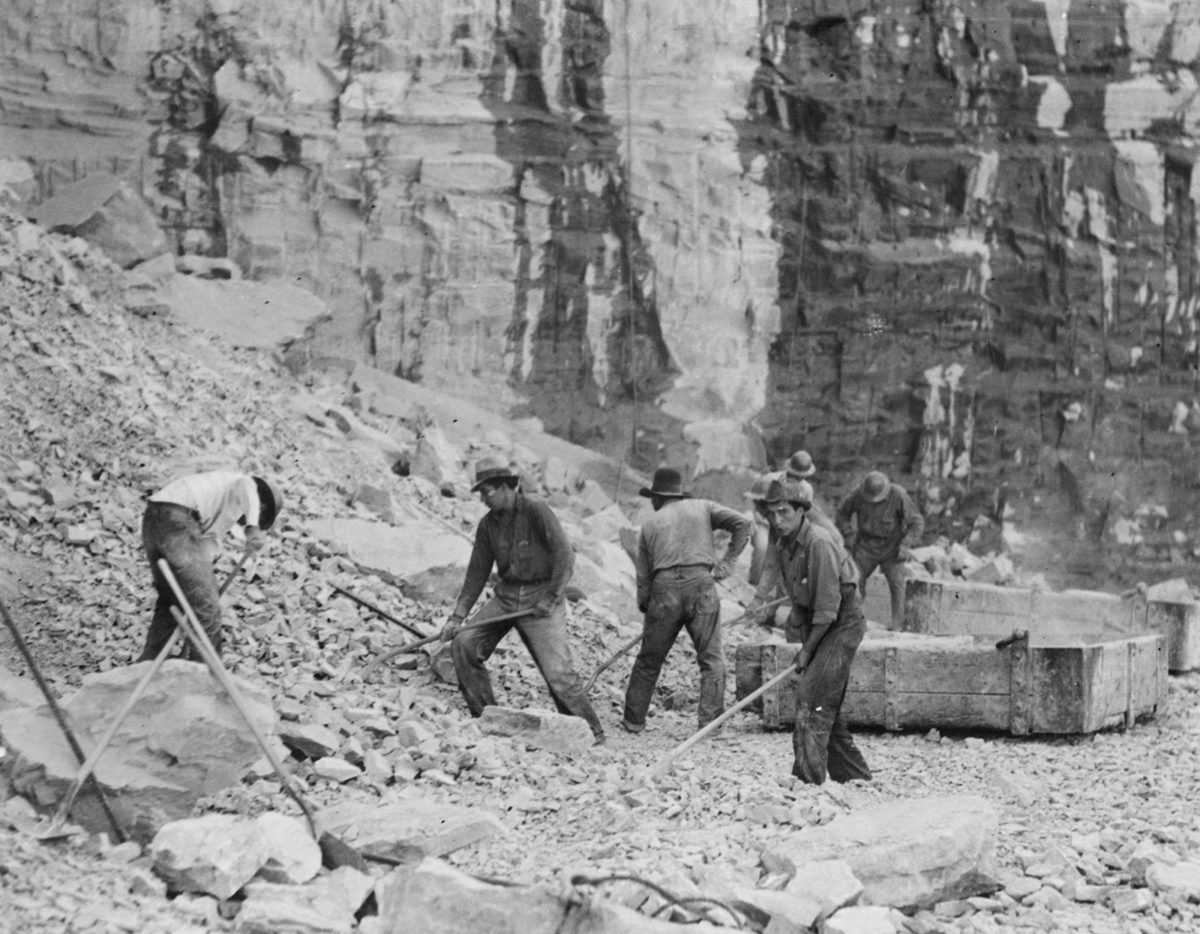

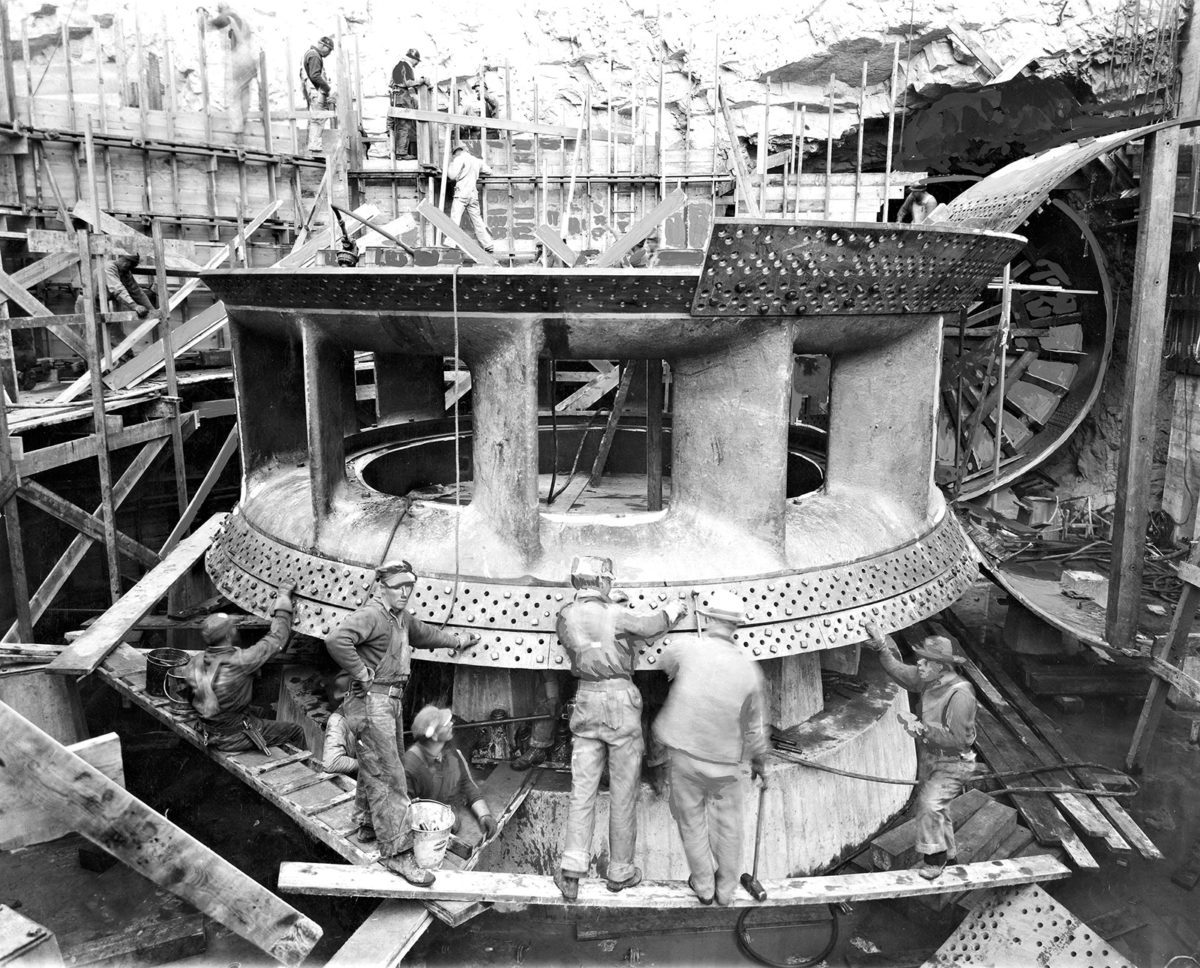

The jobs at the Polson dam project paid between 40 cents and $2 per hour. There were plenty of takers. At its peak, the dam project on the Flathead River employed about 1,200 workers.

As was the case with other big Depression-era dam projects, the jobs came at a deadly price. At the Fort Peck Dam project in northeast Montana, 59 workers died in construction accidents, while many others suffered, and eventually, died from dust-related disease resulting from the construction of tunnels through the big earth-fill dam. To the west in Washington state, work accidents at the Grand Coulee project on the Columbia River claimed 78 lives. The death toll at the much smaller Polson dam project reached 15. The majority of those killed were tribal members.

The first death on the project came on Feb. 2, 1931, just a few months before work was initially stopped. Albert Gerry was working on a tunnel that would divert the river around the dam site when witnesses said he lost his balance and fell into the river. Despite the use of dynamite to try to dislodge rocks that might have trapped Gerry, his body was never found.

When work resumed a half-decade later, the pressure to complete the project quickly was intense. By early 1937, work was taking place in three shifts, 24 hours per day. Two days into February, a work train hauling coal and a work crew to a construction camp near the dam site derailed as it descended a hill. More than 20 workers on the train were able to jump into snow banks along the tracks and escape serious injury.

Conrad Davis, 47, and Jessie Rojas, 39, apparently unable to jump, were killed, crushed beneath tons of coal that spilled from the train. A locomotive engineer told investigators he tested the train’s brakes at the top of the hill, but as the train descended, ice on the rails left the brakes unable to slow the train, causing it to leave the tracks. A coroner’s inquest concluded the accident and deaths were unavoidable.

While the early deaths were dutifully reported in the Flathead Courier newspaper in Polson, a deadly incident on March 3, 1937 made news across the state. “Seven Bodies Under Big Earth Slide in Canyon” read the Missoulian’s front-page headline. To the east in Great Falls, home to four dams and the center of Montana Power’s electric generation operations, the event described as a “rock avalanche” was of high interest.

With water diverted through a large tunnel, work was under way in the river bed, where concrete would form the base of the dam. There were about 60 men in the area on the graveyard shift when “without warning and with startling suddenness,” according to the Courier, a portion of a tall cliff on the river’s north bank broke loose “crushing to death instantly seven men who were at work in that particular place.” Three other men who were working nearby rushed to the scene and were injured by subsequent rock falls from the cliff.

Investigators estimated the slide buried the men under at least 1,000 tons of rock. Rescue and recovery work was delayed until officials were convinced the rock falls had ended. Removing the bodies took several days, with some of the boulders so large that they couldn’t be moved with a bulldozer. Small charges of blasting powder were used to break up the rock and allow it to be moved by a steam shovel.

Killed in the initial rock fall were Dave Sanchez, Clifford Gendron and Jack Anderson of St. Ignatius; Tony Adams of Evaro, Henry Couture and Joe St. Germaine of Arlee; and Allen Ross of Polson. One of the injured rescuers, Harold McNeeley, died a few days later. Most were married and had children. All but one of the dead were tribal members, the Missoulian reported.

Investigators noted that “scaling work” intended to remove possible hazards on the cliff, which was about 170 feet high, had been completed before the accident. C.H. Tornquist, a superintendent for the construction company, concluded the slide was likely caused by rocks loosened when the winter’s frost went out.

Slightly more than a week later, another worker, James “Blackie Emerson, 34, was killed and two co-workers injured when a seven-ton steel beam collapsed in a tunnel leading to the dam’s power house.

About six months after that deadly March, three more men were killed on Sept. 3, 1937, while digging a trench. An embankment above the trench collapsed and trapped the workers under dirt and rock. A fourth man was partially buried but rescued. The lost lives of Paul Innes, 35, of Ronan, Baptiste Pierre, 41, of Arlee and John Mathias, 28, of Elmo, pushed the dam’s construction death toll to 15.

Despite death and injury, work on the dam never abated. Less than a year after the last deaths, the dam was complete and the Polson area again celebrated what was viewed as one of western Montana’s largest industrial developments. The dam was “a boon to both the redman and whiteman of Montana,” according to one news account.

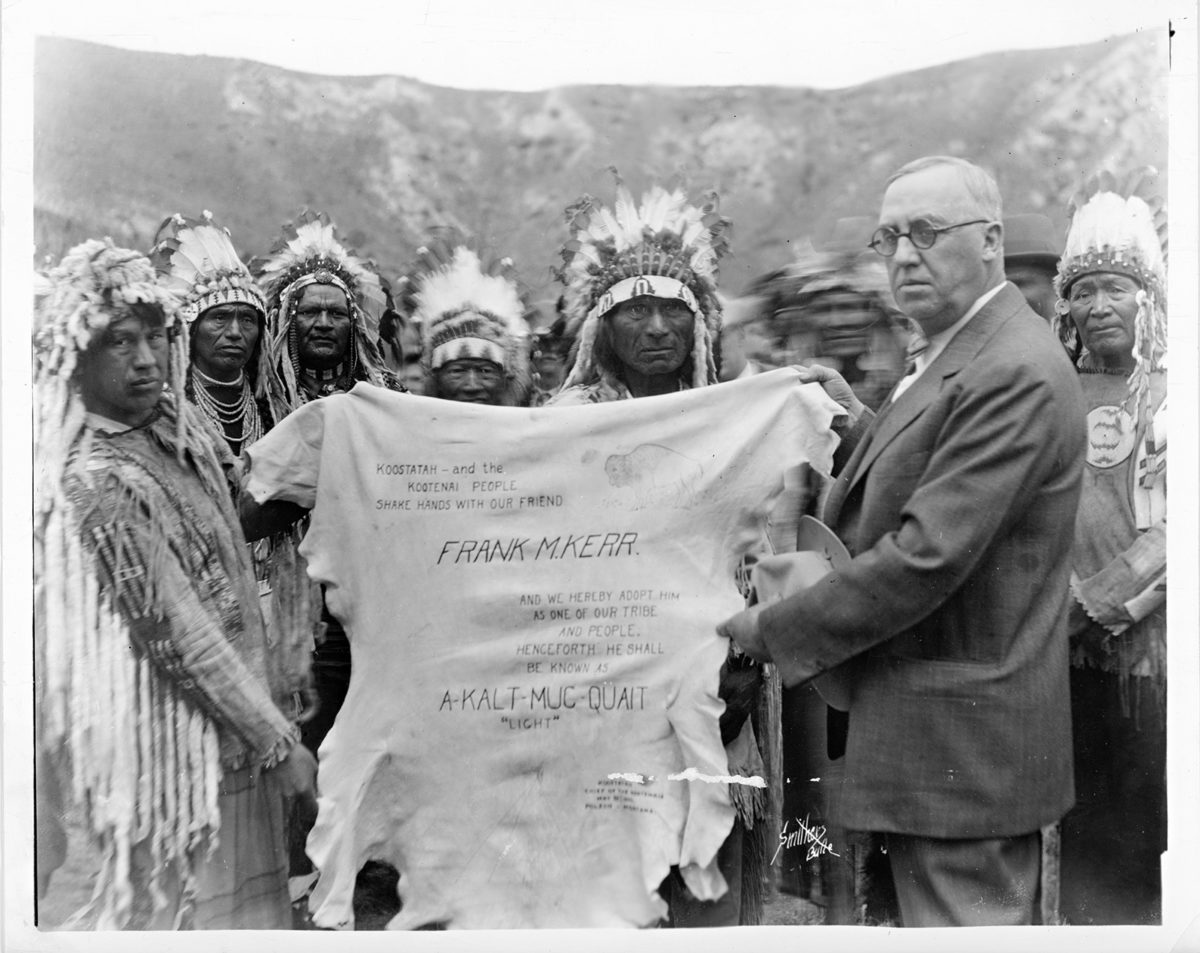

Thousands of residents and tribal members were joined by Montana Gov. Roy Ayers, U.S. Sen. Burton K. Wheeler, Salish Chief Martin Charlo and Kootenai Chief Koostatah Big Knife at the dam site on Aug. 6, 1938, to dedicate the dam and formally name it after Frank Kerr, the president of Montana Power. There was a band concert, native singing and dancing, tours, a barbecue of five young bison, photographs and speeches.

Cornelius “Con” Kelley, the president of Anaconda Copper, hailed the hard work and vision of Kerr and said the tall concrete dam allowed the use of energy “wasted” in the cascades and falls of the river to be used for “industrial purpose and social service.”

Chief Koostatah, the last of the hereditary Kootenai chiefs speaking through an interpreter, noted that the day “marks the time when great motors start to make the juice to make the white people happy and bring the money from the white people to our people.”

In 2015, the CSKT, which had begun saving money three decades earlier — as much as $500,000 per year — to buy the dam, paid NorthWestern Energy $18.3 million and took full ownership. Shortly thereafter, the tribes won federal permission to change the dam’s name from Kerr to Selis’ Ksanka Qlispe, an act that Lipscomb described at the time as “an honor to our people, who sacrificed so dearly in both the construction and acquisition of this facility.”

Butch Larcombe worked for three decades as a newspaper editor and reporter, as well as editor of Montana Magazine. He lives near Woods Bay.