The Wandering Wolf

Two decades ago, a research wolf from Banff, Alberta traveled 300 miles down the spine of the Rockies into Northwest Montana, where its tracking collar was recently recovered, shedding light on the natural dispersals of wolves as they move between places of protection and peril

By Tristan Scott

The story of how a tattered leather research collar from Banff National Park turned up in a snow-choked drainage west of Kalispell begins more than two decades ago, in the autumn of 2001, when a juvenile female gray wolf began transmitting valuable tracking data to biologists with Parks Canada.

The researchers were studying wolf dispersal and how the cross-country treks of lone wolves can improve genetic diversity among a keystone species in recovery. Their research methods occasionally involved tracking the large carnivores on epic transboundary journeys, which criss-crossed a patchwork of management regimes and jurisdictions as individual wolves moved between places of protection and peril. The researchers wanted to learn the stories of what happened on those journeys. Sometimes, they learned that the wolves wandered off to distant territories to see about joining another pack, within which their chances of succession to the ranks of a breeding alpha pair could improve; other times, the wolves took their long walks as exploratory forays before returning to intern with their source family, back where their stories started.

The story of the battered old tracking collar inscribed with a Parks Canada insignia and the moniker “Wolf No. 57” might have ended less than two years after it began, on July 11, 2003, when its VHF transmitter chirped out a final dispatch to a researcher’s radio receiver, registering the wolf’s last-known location at Two Jack Lake near the Bow River Valley of Banff, Alberta, a federally protected region that gray wolves began recolonizing in the 1970s and ‘80s. Since then, wolves have recovered as a species largely through their natural dispersal methods, traveling vast distances to find new mates and territories, which helps promote stronger lines of breeding — what scientists call genetic diversity. Following extirpation of the species from its historic natural habitat range, including across Canada and the U.S., the recovery of gray wolves stands out as the greatest success story of an endangered species because of their ability to disperse.

The story of Wolf No. 57’s dispersal might have ended there, but it didn’t.

Instead, in December 2021, a shed-hunter’s virtuous instincts compelled him to excavate the beat-up old collar from its frozen, earth-caked cavity and deliver it to the Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) headquarters in Kalispell, 300 miles from where it started, in a region where researchers also happen to be studying the stories of wolves, with greater interest than ever. Because of that random node of connection, the story’s trajectory is complete, even if much of the narrative has been filled in with blank spaces and bread crumbs, and even if its conclusion remains maddeningly unsatisfying due to the inability of anyone to answer the most basic question: What happened to Research Wolf No. 57?

“The story is a little bit of … it just closes the circle,” said Dan Rafla, a human-wildlife coexistence specialist for Parks Canada, upon learning of the research collar’s recovery. “This wolf, she has been long forgotten, as have lots of other wolves who were collared during that time period. At the time, research students were performing telemetry work to pinpoint where exactly those wolves went. But in the case of Wolf 57, we don’t know the precise path she took or how she died or what kind of life she led, which some people might not find very satisfying. But the heart of the story is that, 20 years ago, she made it from Banff to Montana, and because we have continued to monitor the movements of wolves, we know that, 20 years later, there is still the possibility for wolves and large carnivores to make these long-range journeys across connected wildlife habitat corridors. And that is quite remarkable.”

Wolf/Carnivore Specialist Wendy Cole for Region 1 of Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks holds a tracking collar from a wolf that migrated from Banff National Park to Little Bitterroot Lake in Marion at FWP Region 1 Headquarters in Kalispell on Feb. 23, 2022. Hunter D’Antuono | Flathead Beacon

Cradling the old collar in her mittened hands outside the FWP office in Kalispell, marveling at its origin story and somewhat incredulous that it ended up here, Wendy Cole agrees.

As the wolf and carnivore specialist for the state agency’s expansive, carnivore-rich Region 1 territory in northwest Montana, Cole pays close attention to the transboundary dispersals among the “metapopulations” of local wolves, whose residents don’t always stay local for long. Indeed, the ability and proclivity of wolves to disperse is what makes the species so resilient, and its recovery in Montana — where an estimated 1,177 wolves now roam after having been hunted to the brink of extinction during the last century — wouldn’t have been possible without individuals like Wolf No. 57, a lone wolf who struck out on her own in search of a new beginning.

“Even people who don’t really like wolves for a variety of reasons will admit that their doggedness and resilience is impressive,” Cole said. “They live by their feet and they cover a lot of ground. Their territories are enormous and their dispersals outside of those territories, either as exploratory forays or as a means for submissive non-alpha wolves to find an opportunity to breed within new packs, is what has enabled their biological recovery. It’s fascinating.”

According to information cobbled together by Cole and Parks Canada wildlife ecologists, Wolf No. 57 was born into the Fairholme pack in Banff in 2001 when, as a young of the year, she was fitted with a radio-tracking collar. In March of 2003, researchers initially lost her signal before picking it up again some 30 miles away, in Kananaskis Country, where the wolf apparently made an exploratory foray before returning to her pack in Banff. She stayed with the pack until that July, when the collar transmitted a last-known location from near Two Jack Lake before falling silent.

What happened after that is based on supposition and the collar’s final resting place near Little Bitterroot Lake in Marion, which likely marked the final resting place of Wolf No. 57, although the shed-hunter who discovered the collar said there was no evidence of skeletal remains in the area, and Cole says the collar had no smell, although any trace of decomposition would have been expunged by time.

“Even though we don’t know exactly what happened to Wolf 57, we at least know her final destination,” Cole said. “If a collared wolf disperses and it’s not wearing a GPS tracker, which was the case here, we lose the signal. A lot of the time we’ll hit the trail or fly around trying to find it again. But if the wolf has traveled 300 miles we probably aren’t going to find it again. So we often don’t find out the ultimate destiny of that wolf. But if someone brings in a collar, even it’s no longer functioning, that’s valuable information. Sometimes you put a collar on a wolf and it’s harvested by a hunter a few months later. That’s disappointing from a research perspective, but it’s still helpful information to have.”

Indeed, in the nearly 20 years that have passed since the last-known whereabouts Wolf No. 57, technology has evolved and the body of research into wolf dispersal has advanced. Today, researchers use GPS trackers to monitor an animal’s movements, allowing them to download precise locations after the unit is recovered, either due to the animal’s demise or because the collar self-releases.

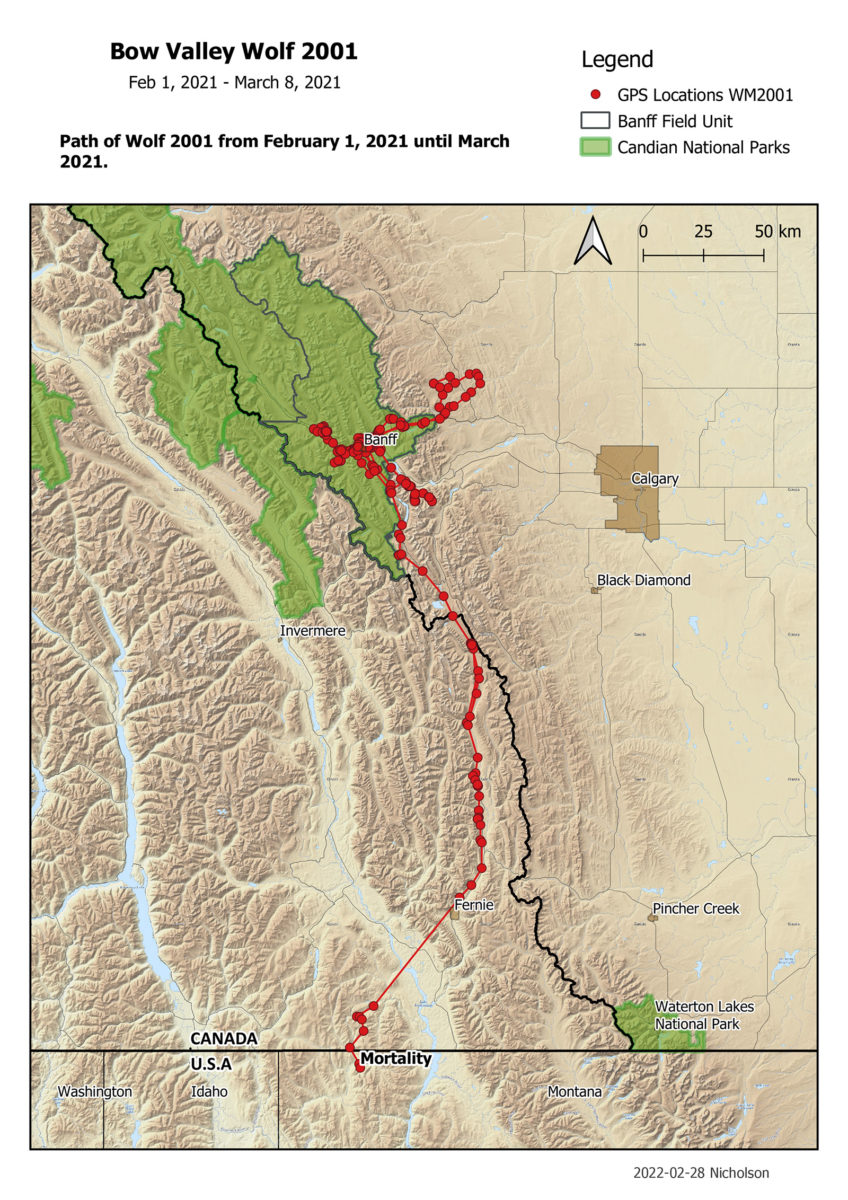

Last March, for example, a 2-year-old male collared wolf (Research Wolf No. 2001) left the Bow Valley and headed south to Montana, but was legally shot and killed a mere four hours after crossing the international border into the Yaak River Valley. Having traveled more than 300 miles in several days, Wolf No. 2001 likely charted a similar course along the same wildlife corridor as the one used by Wolf No. 57. That corridor serves as the northern tier of a conservation region that’s popularly known as the Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y), and the wolf dispersals serve to illustrate the significance of preserving a connected landscape spanning more than 2,100 miles.

According to wildlife experts, large carnivores — and wolves in particular — need large, connected landscapes to thrive, and research wolves like 57 and 2001 provide clear evidence of how wolves use those open spaces.

“This wolf’s movements show that the Yellowstone to Yukon region is still connected. It also points to the major challenge that most park wolves face if they leave parks, which is human-caused deaths,” according to Jodi Hilty, president and chief scientist of the Y2Y Conservation Initiative.

Although the demise of research wolves by human-caused means is testament to the perils animals encounter after leaving protected areas like national parks and wildlife refuges, it also helps shore up evidence of wide-ranging dispersals that have allowed the species to thrive on a landscape fragmented by development.

“It’s believed that for every collared wolf that makes those dispersals there are many, many more uncollared wolves who are doing the same,” Cole said. “The fact that we can capture a small number of these movements with collar data emphasizes that many more are making similar journeys in anonymity, recorded only in the genetics of their new territories that function as arms of the wolf metapopulation across western North America.”

“Given that such a small percentage of our wolves are collared, you can assume that there are uncollared wolves making that journey,” added Rafla, the Parks Canada biologist in Banff. “You can also assume there are uncollared wolves that are not making that journey, because as soon as they leave the protections of the park they encounter the difficulty of coexisting with humans and they are killed. But it still speaks to the importance of large landscape connectivity, which helps accommodate carnivores like wolves as they make large-scale movements.”

The fact that those large-scale movements are often abridged due to conflicts with humans, including legal hunting and trapping — or because of run-ins with landowners that arise as a result of livestock depredation, or because of highway collisions — is what wildlife managers like Cole must consider every day when taking stock of how the natural world behaves in an increasingly unnatural environment, where polarizing political powers have regained their potency in recent years.

Through hunting, poisoning and habitat removal, humans had effectively eliminated wolves from the Mountain West by the 1930s, and while the ensuing decades have come to spell the most successful recovery story of an endangered species in the history of U.S. wildlife management, the wolf is still reviled by many. For example, the most recent state legislative cycle churned out an unprecedented volume of wolf-management measures engineered to expand opportunities for hunters and trappers to harvest wolves, even though harvest rates have remained steady through the years, and current FWP harvest figures reveal a decline in wolves killed by hunting and trapping this year (86 wolves harvested) when compared to the same time last year (120 wolves harvested).

In a high-profile incident last year, Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte trapped and killed a radio-collared wolf near Yellowstone National Park, doing so without taking a requisite trapper education course, which is a violation of state hunting regulations. The wolf Gianforte killed, dubbed Wolf No. 1155 by park researchers, belonged to a Yellowstone pack and had been studied by biologists since 2018. While wolves are protected within park jurisdiction, it was harvested on private property outside the protected boundary. And although Gianforte received a warning, the news touched off a heated debate about the role that hunting and trapping plays in the management of a recovered species that nearly went extinct due to cultural vilification.

Still, even as the politics of large carnivores like wolves remain polarizing, the biology that drives their natural behavior is unifying in its tendency to fascinate all comers, says Cole, who helps teach trapper education courses, which she says provide her an opportunity to interface with a segment of the population that observes wolf behavior through a unique prism.

“I also get a ton of valuable information from talking to hunters and trappers at our harvest inspection stations,” Cole said, adding that she recently joined a trapper in the field to check his lines and exchange information about wolf ecology and the shifting characteristics of the landscape. “They help us with our estimates of pack sizes, they help us learn about how the snowpack is affecting the distributions of animals on the landscape, and they always seem interested to hear about what we’re learning on our end. I think there’s a mutual respect for wolves that’s pretty universal.”

For John and Kate Hanson, whose family has raised cattle for generations on their Marion ranch — situated, as it were, not far from Little Bitterroot Lake and Griffin Creek, where Wolf No. 57’s collar was recovered last December — wolves have been a persistent source of aggravation for decades, jeopardizing their livelihood by killing calves, sometimes before their spindly legs hit the ground each spring.

Until, that is, the Hansons adopted a progressive approach to curbing livestock losses to wolves, a common problem for ranchers, which the family resolved through the use of electric fencing and a centuries-old technique called “fladry,” a deterrent consisting of orange flags affixed to strands of high-tensile electrified cordage, which exploit wolves’ innate fear of unfamiliar objects in their environment.

“We had seven wolves come through last night,” Kate Hanson said last week. “We caught them on the game cameras. They came down and inspected the perimeter, where the fladry is, and then left. Last year we didn’t have any wolves but everyone around us had wolf problems. So they’re obviously still around, but our livestock losses sure have lessened.”

For biologists like Cole and Rafla, their interests in wolves and other large carnivores is rooted in the disproportionately important roles they play in ecosystem function and conservation, including having direct effects on reducing large ungulate populations through predation and indirect effects on lower food web levels through the phenomenon of what biologists call “trophic cascades” — or, the indirect interactions between predators and prey that can control entire ecosystems, and even affect agriculture.

“We’re overrun with cow elk,” Hanson said. “They eat our hay like it’s going out of style and then they take off on opening day of hunting season. Who knows what would happen to the elk population if those wolves weren’t around.”

Whether people love them, hate them, or tolerate them, wolves are an iconic species, the biologists say, and they serve an important ecological role on the landscape.

Meanwhile, anyone wishing they knew what happened to Wolf No. 57 can rest assured they’re not alone, Cole and Rafla said, noting that the curious case of the missing wolf collar has been a source of fascination for researchers at agencies on both sides of the international border. But even if many of the answers about Wolf No. 57’s story remain elusive, the researchers take comfort knowing that her remarkable journey served to further the ongoing recovery, management and understanding of a keystone species on a wild landscape.

“As the world becomes more developed, we should take time to appreciate the fact that we set these pieces of land aside to allow genetic movement, which allows the population to be more resilient. It’s not about the individual wolf. It is really about those large-scale landscape movements, and that is what this demonstrates,” Rafla said.

As for the old leather tracking collar, at the time the Beacon went to print it was en route to Rafla’s office at Banff National Park, back to where it originated more than two decade ago, traveling this time via the U.S. Post Office.

“I was just at the Post Office mailing the collar back to Dan Rafla,” Cole explained last week. “I confused the Post Office employee because under description I wrote, ‘old radio collar from wolf.’ When he asked for clarification, I explained that it had been put on a Banff wolf in 2001 and the wolf dispersed here naturally. He looked thoughtful for a moment and said, ‘Isn’t Banff really far?’”

“I concurred,” Cole said.