Pioneering Mountaineer Chronicles Tragedy and Triumph in Glacier Park

Upcoming Wilderness Speaker Series features Terry Kennedy, a renowned climber and Columbia Falls native whose mountaineering book centers on the infamous 1969 'Mount Cleveland Five' disaster

By Tristan Scott

In December 1969, a prolific 18-year-old mountaineer from Columbia Falls named Jerry Kanzler set out with four other ambitious locals to scale Mount Cleveland’s unclimbed north face, eager to claim the elusive grail of first ascents remaining in Glacier National Park. Two days after Christmas, the five climbers were swept to their deaths in an avalanche, sending shockwaves across the Flathead Valley as one of the most enigmatic mountaineering accidents in the nation’s history unfolded.

The tragedy and its aftermath would leave an indelible mark on Hal and Jim Kanzler, Jerry’s father and older brother, respectively, both of whom eventually died by suicide. It also signaled a turning point in the life of Terry Kennedy, another young climber who grew up on the doorstep of Glacier Park, and who became fascinated by the Kanzler family and their climbing feats.

“When I look at my heritage and think about how I became a climber, it goes back to the Kanzlers,” Kennedy said. “I mean these guys were really out there. This was back in the days of early space travel and putting a man on the moon, and I held the Kanzlers at the same level as that. We knew that the Kanzlers were mountain climbers. And that was like being an astronaut, as far as we were concerned.”

In Kennedy’s 2017 book, “In Search of the Mount Cleveland Five,” the author captures how the mountaineering accident rocked the region’s nascent climbing community while articulating the grief and ambition that drove a clutch of local climbers to push the sport into a brave new era.

On March 10, Kennedy will discuss his coming-of-age mountaineering book as the featured guest of the Wilderness Speaker Series at Flathead Valley Community College. Hosted by the Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation, the Northwest Montana Lookout Association and the Flathead-Kootenai Chapter of Wild Montana, the Wilderness Speaker Series also receives support from FVCC and its Natural Resources Conservation and Management program.

Looking back on the 1969 tragedy after nearly a half-century, Kennedy frames the book around the climbing partnership he forged with Jim Kanzler, who was six years older than Kennedy and, along with his brother, Jerry, had already developed a reputation as a talented big mountain climber, which swelled to mythic proportions for the younger kids.

“All of our fathers worked at the Columbia Falls Aluminum Company plant, and we’d look up at Teakettle and Columbia mountains and want to climb them. So we did,” Kennedy said. “We would go up there and shine mirrors down to our houses for our moms to see. It was pretty special.”

Growing up on the outskirts of Glacier, the gravity of the Kanzlers’ climbing feats gripped Kennedy in particular.

In 1963, Hal Kanzler led his sons up Mount St. Nicholas, a steep, technical and remote climb that is considered one of the most challenging summits in Glacier. At the time, Jim Kanzler was 15 and Jerry was 12, and rumors of the hideously difficult ascent quickly spread through the community.

“The kids at school were all talking about how the Kanzler boys had climbed some really big, scary mountain in the park,” Kennedy recalled. “We were going, ‘Wow, really? Which one?’ It turned out these kids had climbed St. Nick. That was a profound influence on me.”

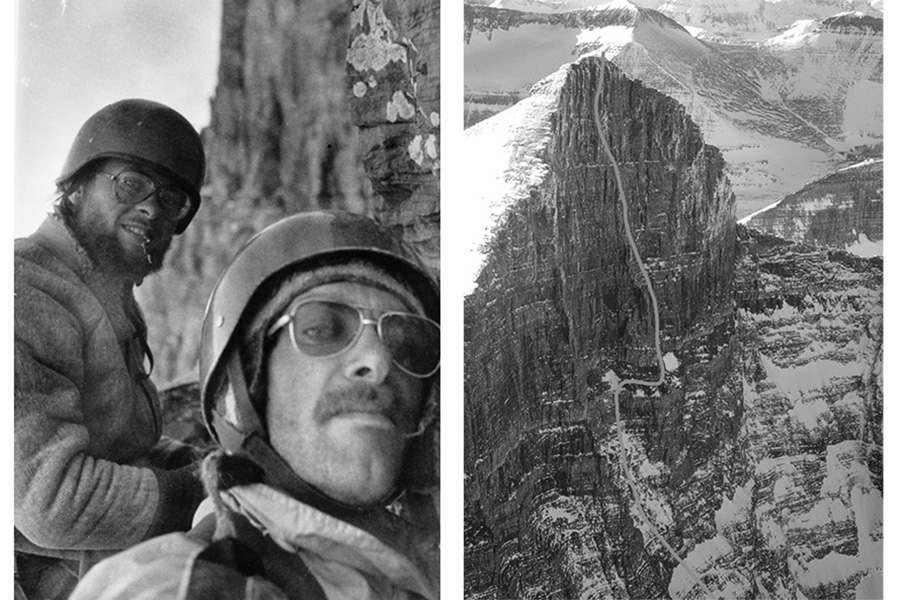

After Jerry’s death, achieving Cleveland’s north face became critically important to Jim Kanzler and Kennedy, and the pair launched an all-out assault on the park’s tallest mountain. A first ascent of Mount Cleveland’s north face was widely regarded as the most difficult technical mountaineering project in Glacier, and it was crucial to both Kanzler and Kennedy that it was set by locals. Indeed, it was J. Gordon Edwards’ ominous description of both the north faces of Cleveland and Siyeh as “unclimbed” and perhaps “unclimbable” that so entranced the Kanzlers and Kennedy. Both peaks loomed at the forefront of their imaginations.

In 1976, after the friends finally succeeded in summiting the north face of Cleveland, they decided to commit all their energy to climbing the park’s other big unclimbed face, the north face of Siyeh — a Blackfeet word meaning “Mad Wolf.” The ascent required 3,500 vertical feet of technical climbing (the Nose of El Capitan, by comparison, is about 2,900 feet high), 22 pitches and two cold nights on the rock face.

Over the course of three days in September 1979, the 25-year-old Kennedy and 31-year-old Kanzler inched their way up the sheer north face of Mount Siyeh. The duo had attempted the route three times prior; they succeeded on their fourth attempt after spending two cold nights suspended from the massive wall.

“Jim and I both referred that period as being the Siyeh years,” Kennedy said. “Everything we climbed, every mile we ran, every pull-up was in preparation for that climb. It was a single-focus vision kind of thing.”

As leading forces of Glacier climbing in the 1970s, Kanzler and Kennedy set a standard that endures today.

“I’ve been wanting to write this book since I was a kid dreaming of climbing mountains,” Kennedy said at the time of. “I realized early on that something special was happening, and the Mount Cleveland tragedy sort of ushered in a new era of climbing in Montana.”

The Wilderness Speaker Series is held in the Large Community Room (#139) at FVCC’s Art and Technology Building from 7-8:15 p.m. There is no charge for the community events and all are welcome to join the discussion. To learn more about the Wilderness Speaker Series, visit bmwf.org/wss