The Spaces Between

With modest beginnings as a surf-bum turned dolphin trainer, Jim Williams forged a distinct path to become chief of the state’s regional Fish, Wildlife and Parks office in Northwest Montana, where he leaves behind a lasting legacy of conservation and wildlife management

By Tristan Scott

Twenty-five years ago, as a young wildlife biologist ascending the management ranks at Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Jim Williams came to a realization that he was spending more time drinking cowboy coffee with exasperated landowners on the Rocky Mountain Front than he was tracking large carnivores across tracts of wild habitat.

With an early background as a marine mammal trainer at Sea World in San Diego, California, and later as an alligator wrestler and shark tamer at Ocean World in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Williams settled on his career path as a biologist — however unconventionally — guided by a deep and committed love for the natural world and a childlike wonder at its infinite potential for discovery.

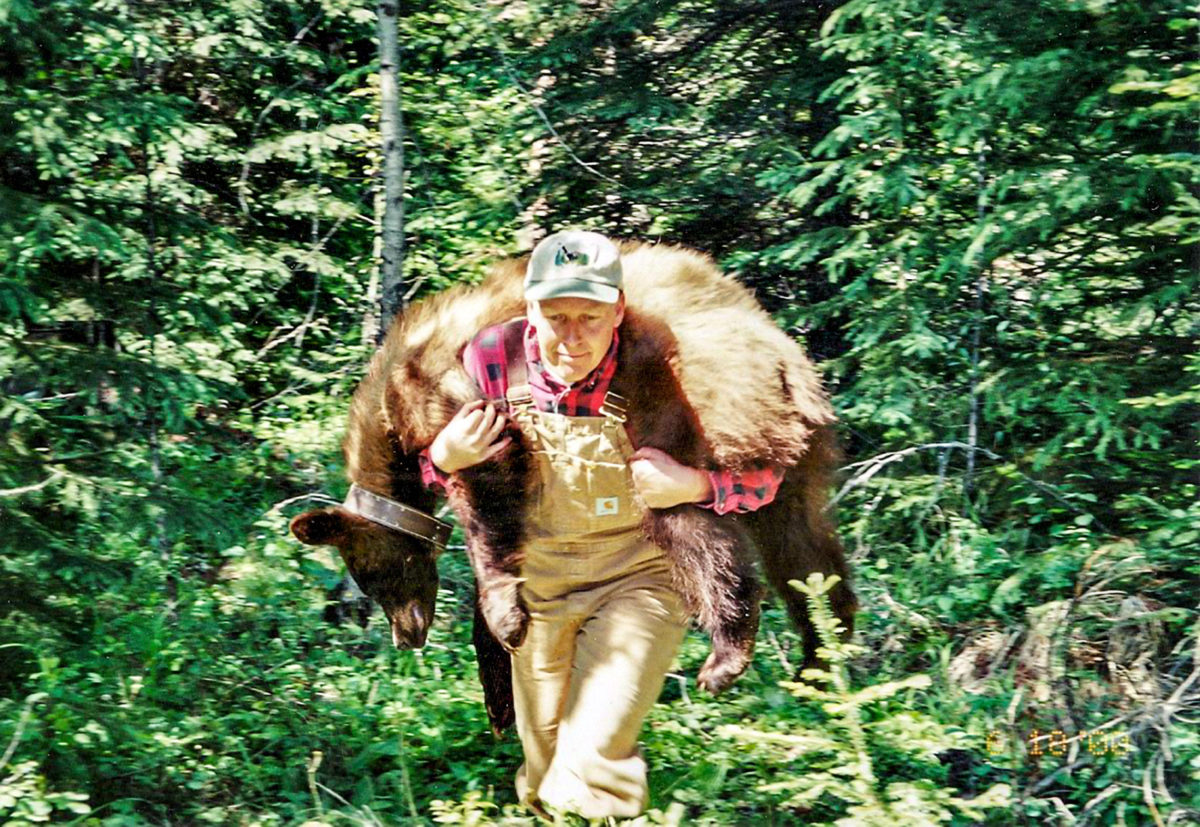

He’d spent three years performing fieldwork on mountain lions in the rugged Bob Marshall Wilderness, earning his masters thesis at Montana State University by studying the health and habits of big cats in big country. Possessing the curiosity and enthusiasm of a 10-year-old boy, Williams saw the wilderness as his laboratory; he was meant to study wild things in wild places, not serve as a mediator to a bunch of pissed off sheep ranchers.

Unless, he thought, both could be true.

After all, he’d gained plenty of administrative experience training dolphins and wrestling gators, and his wildlife management decisions in Montana had been smoothest and most effective whenever he had the buy-in of the public — the ranchers and landowners and hunters and fishers who occupy what Williams calls “the spaces between,” those nodes of connection bridging islands of protected habitat with a human-occupied landscape brimming with wildlife.

If he could build consensus in those spaces, he reasoned, perhaps both people and wildlife could benefit. Or at least they could learn to coexist.

“People have an emotional connection to fish and wildlife. There’s cultural value in our natural resources and, because everyone has the right to fish and hunt, there’s a Democracy to it,” Williams said. “Jim Posewitz [the conservation legend and a mentor to Williams] called it ‘the Democracy of the Wild.’ I am a firm believer in that. Everyone wants to play in wild places. And if we can ensure access to them, then everyone is going to care about those wild places. If everyone can’t play in them, or if only certain people with certain means can play in them, then not everybody is going to care.”

With that guiding principle in his back pocket, Williams navigated the spaces between by building relationships with the people in them, and by giving them a reason to care.

By mending fences with the ranchers reeling from livestock depredation on the Front, he forged alliances and laid the groundwork for lasting conservation successes. By ensuring neighbors that he’d prioritize their public safety above all else, he earned their trust. And by making the difficult decisions to remove habituated carnivores from urban centers, sometimes by lethal means — a decision that never grew easier for Williams; not when he assumed the position in 1999 as wildlife manager for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks’ (FWP) regional headquarters in Kalispell, and not when he stepped into the role as its chief — he helped others avoid conflict in the first place.

Indeed, Williams has spent much of his 30-year career working with local communities to conserve mountain lions, bears, wolves, large ungulates, and their critical wildlife habitats. As he retires from his post at the helm of FWP’s Region 1 office, those who worked with him say he leaves behind a legacy of resource protection and habitat stewardship that will be felt across northwest Montana for generations to come.

“Jim has this infectious enthusiasm coursing through him. He is guided by the wonders of wildlife and of the natural world. He’s still that kid rolling the rock over to see what’s beneath,” said Michael Jamison, a writer and conservationist whose work for the National Parks Conservation Association often dovetails with state and federal wildlife management agencies. “But even though he comes at his work from the place of a true believer, as someone who believes in habitat and its ecological value, he’s smart enough to understand that nothing is possible without people.”

For Williams, that core belief has endured some spectacular tests of faith, but perhaps never more so than in the winter of 1996, when the world he occupies as a people person and the world he occupies as a puma person collided.

“When it comes to mountain lions, especially, I believe that our energy should be directed toward protecting big and connected habitats, and toward increasing human acceptance and tolerance,” Williams wrote in his 2018 book “Path of the Puma: The Remarkable Resilience of the Mountain Lion,” which was published by Patagonia and draws on decades of research and expertise Williams cultivated in the field. “Which is exactly what I was doing, shotgun at my side, as I pulled into the suburban driveway of the house with the lion under the barbecue deck.”

As the basis for his post-graduate studies, Williams was enthralled by mountain lions, which he considered his favorite among the animal kingdom — and among his least favorite to have to capture and kill.

“Mountain lions are spectacular and beautiful animals … and I had to shoot this one,” Williams wrote. “It was a bad day for us both, and when they pulled me out, lion in hand, it didn’t really matter that I knew I’d done what needed to be done. Knowing that you’re protecting the big wild cats, and protecting people, and protecting wild nature. Knowing that mountain lions should not be allowed to live in suburban neighborhoods. None of that makes it any easier, at least not in the moment.”

Back in the winter of 1996, that moment was especially fraught on the heels of a record winter, with heavy snows cutting the local deer herds in half and leading to a food scarcity for mountain lions, and in turn sending a lot of big cats prowling unusual places in search of a meal. It also sent wildlife managers on a mad dash from crisis to crisis as human-lion conflicts ramped up across the Flathead Valley.

“Lions in basements. Lions crouching under exercise bicycles. Lions in living rooms. Garages. Dog kennels. Downtown alleys. Golf courses. Lions everywhere they might find a meal, and not necessarily a wild meal,” Williams wrote, describing how he and wildlife-conflict biologist Erik Wenum enlisted the help of local houndsmen (mountain lion hunters) to kill a number of habituated cats.

One of the houndsmen was Terry L. Zink, who has more than four decades of experience trailing big cats with the help of his well-trained dogs and has caught more mountain lions than he can remember.

“Jim hated to do it, but he knew that with so many lions coming right down in the valley, it was going to be a big problem if we didn’t get rid of them,” Zink said. “I mean, we had lions casing kids at school bus stops. One lion stuck its head through a dog door. And Jim listened to the public. He listened to the boots on the ground. Everything Jim does is for the good of the resource, and sometimes shaping public perception is what’s best for the resource.”

In this case, Williams maintained the pressure on the suburban cats just long enough for the seasonal aberration to ease up and, after the ecological balanced had been restored, the public perception did indeed shift. Neighbors understood that habituated cats wouldn’t be tolerated in town, which made it easier for them to tolerate them outside of town, believing that wild cats belong in wild places.

“I probably prioritize land conservation above everything else except for human safety,” Williams said, “because when it comes to carnivore conflicts you have to make human safety your number one. People are a really important piece of the ecosystem.”

To that end, Williams’ career has been distinguished through his years of work negotiating habitat conservation deals in the region, where a complementary network of public and private ownership has helped protect critical wildlife habitat connecting Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area to the Cabinet Mountains Wilderness and the Selkirk and Coeur d’Alene mountains. As he departs FWP, the agency is moving forward on deals that will furnish protections on hundreds of thousands of acres of working forestland extending between Kalispell and Libby, and on timberlands across the region, where development pressure has never been higher.

Under Williams’ leadership, projects like the Montana Great Outdoors Conservation Project have been crafted to maintain public access for hunting, fishing, and recreation while bolstering connectivity on some of the richest wildlife habitat in the West. The Montana Great Outdoors Conservation Project area borders Thompson Chain of Lakes State Park, the 142,000-acre Thompson-Fisher Conservation Easement, and the 100,000-acre U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Lost Trail Conservation Area as well as the Kootenai National Forest and Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation lands.

According to those who worked with Williams to facilitate the conservation projects, they have come to fruition at a critical moment for Northwest Montana’s undeveloped timberlands, a large segment of which have exchanged hands in recent years through a rapid succession of land transactions, casting shades of uncertainty across the landscape. Coinciding as they did with a land rush, the transactions might have spelled trouble for the public’s ability to access the acreage.

But Williams and his colleagues at FWP spared no time in approaching the new owners in an effort to negotiate conservation easements, which allow the landowners to retain ownership of the timberlands and conduct sustainable logging operations while precluding development and protecting critical wildlife habitat.

It also secures the public’s ability to access the land in perpetuity, as the property currently provides abundant public hunting and angling opportunities.

“His is one of the most significant private land conservation legacies out there,” said Dick Dolan, the Northern Rockies director for the nonprofit The Trust for Public Land (TPL). “And you add on top that it’s not just the land conservation but the fact that we have conserved public recreational access, I am at a loss for words to describe the significance. It is such a legacy gift to the public, and its true value will be realized over time.”

True to character, Williams gives all the credit to a “dream team” of agency personnel — people like Kris Tempel, Alan Wood and Gael Bissell, who helped orchestrate the complex land deals between the state and private owners, playing the long game to achieve landscape-scale habitat conservation.

“My role was just to support them through the process and have their backs,” Williams said. “I tried to lead from behind until I absolutely had to get out in front.”

Tempel, a former habitat conservation biologist for FWP who now works for the U.S. Forest Service, learned from her peers and predecessors and joined Wood and Bissell to secure federal and state funding for conservation projects that routinely ranked at the top of the heap nationally.

“I was fortunate to join a team doing amazing habitat protection work, and we were all fortunate to have Jim supporting and championing our efforts,” Tempel said. “Even after we demonstrated a track record of success and we were bringing in some pretty significant funding for conservation work, having Jim’s support from the top was invaluable. He was always telling us to go, go, go.”

Another pressing matter for Williams, both as FWP’s regional wildlife manager and as chief, was improving the agency’s working relationship with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT), whose current chairman, Tom McDonald, formerly presided over its Natural Resources Department’s Fish, Wildlife, Recreation and Conservation Division.

“Tom McDonald has been a mentor to me and he has helped build an amazing natural resource program,” Williams said. “It’s bigger and more sophisticated than anything else out there and I don’t think they get the respect they deserve. My crew has learned so much from them and I hope there continues to be an awakening about the First Nations and their role on the landscape, because their presence is everywhere. This is all tribal land.”

Acknowledging that CSKT’s relationship with FWP has at times been strained, particularly when the agencies’ management jurisdictions and objectives overlap, McDonald said Williams has demonstrated the utmost respect to CSKT while crafting solutions that benefit their shared natural resource and the whole spectrum of public stakeholder.

“He gives so much credit to his mentors but he’s a mentor to us,” McDonald said. “He built a strong relationship with us because of his respect for Indigenous people and for our treaties. He set that tone right away and he didn’t do anything without seeking the Tribes’ approval. He has the ability to engage in real dialogue with people so that everyone walks away feeling good.”

As a parting gift, Williams presented McDonald with a print of a grizzly bear in the Bob Marshall Wilderness, and the tribal leader in turn bestowed Williams with a Pendleton blanket.

“That isn’t something we do for just anyone,” McDonald said. “It’s a symbol of our sincere appreciation for Jim and his leadership at FWP. His ability to bring people together for a common purpose is a great trait. He will be missed but not forgotten.”

Although Williams officially retired from FWP on April 8, he and his wife, Melora, will remain in the Flathead Valley, where in his new role with the nonprofit Heart of the Rockies, a partnership of local, regional and national land trusts, he’ll continue to work in conservation.

“I’ll still be working to protect wild things in wild places,” Williams said. “I really believe that’s something we all care about.”