Art, History, and the Atomic Bomb

Author, illustrator and Flathead resident Jonathan Fetter-Vorm reflects on the 10-year anniversary of his debut book, a graphic history of the first atomic bomb

By Mike Kordenbrock

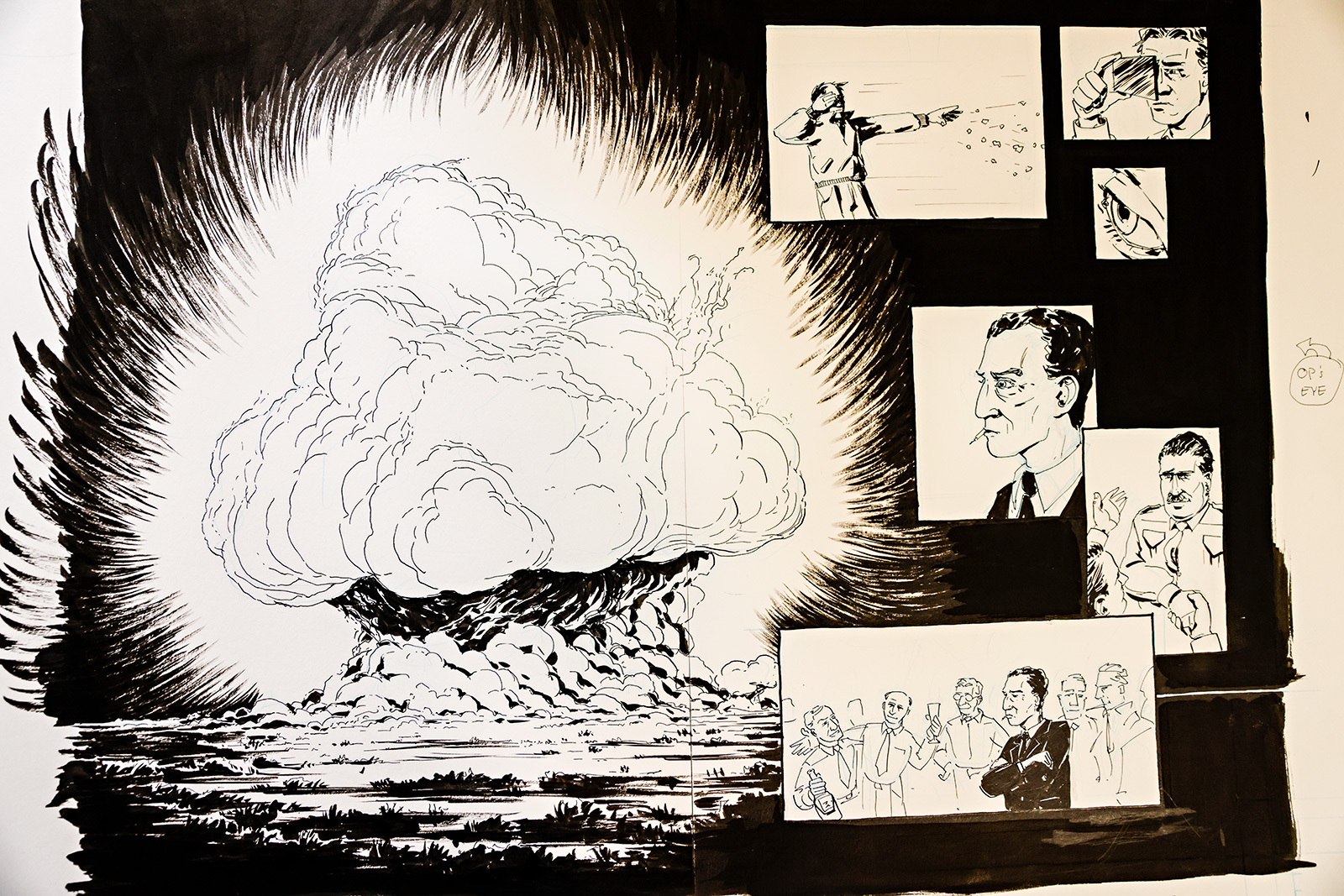

When Jonathan Fetter-Vorm turned in the first draft of his debut graphic history “Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb,” his editor reviewed the copy and delivered the unfortunate news: he didn’t really have an ending.

The Flathead County author, illustrator and artist who grew up in Bigfork had set out to document, in graphic novel form, the American-led development of the atomic bomb during World War II and the consequences of its creation, including the killing of hundreds of thousands of people between the bombings of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Fetter-Vorm relied on a three-part thematic structure organized around the three distinct nuclear bomb detonations he sought to depict—the Trinity test 200 miles south of the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, the bombing of Hiroshima, and the bombing of Nagasaki.

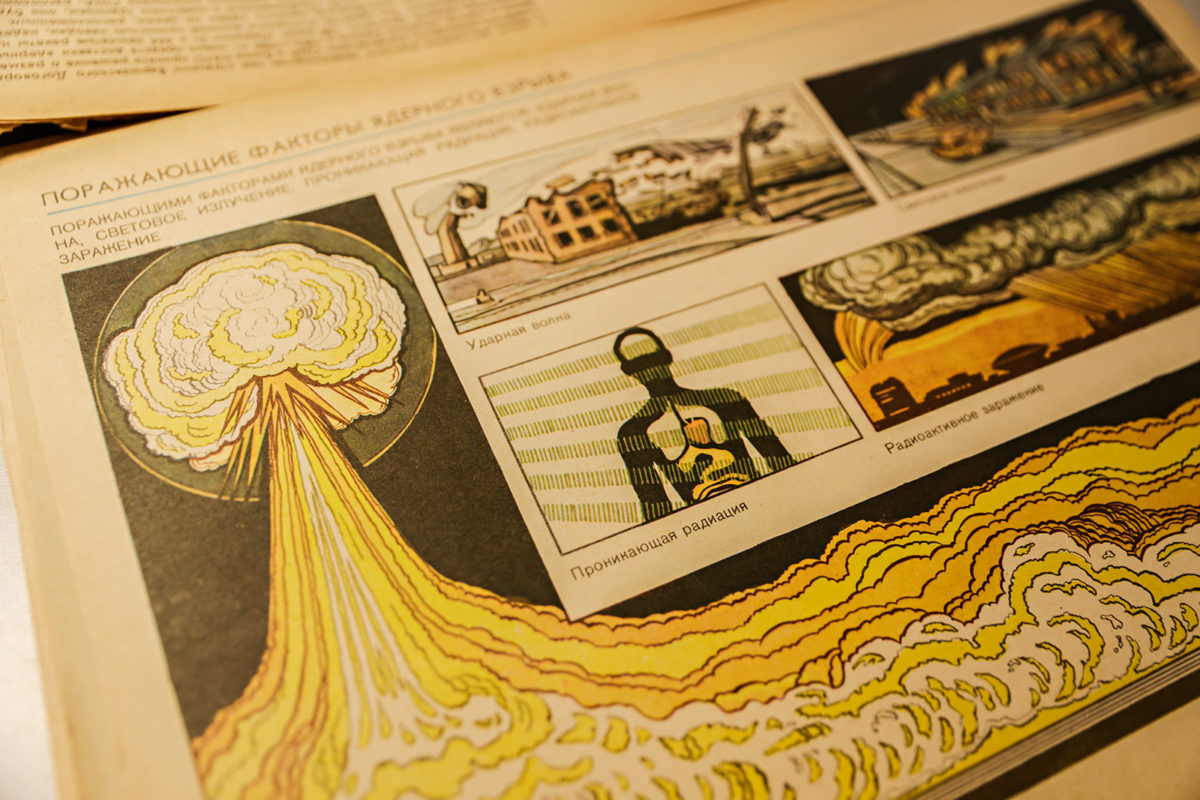

The first section would depict the scientific questions that needed to be answered in order to create the bomb. Next, Fetter-Vorm wanted to describe in technical detail what happens physically when a nuclear bomb is detonated. Lastly, he wanted to evoke the moral questions that arise after seeing what happens to the human beings exposed to nuclear weapons.

In the book’s original ending, Fetter-Vorm introduced the concept of mutually assured destruction, or the idea that an exchange of nuclear weapons between two nations would obliterate both. In one of the final pages, a panel shows a button in a glass case. The text alongside it states that “The world we inherited from the Manhattan Project contains risks that were never present before 1945. It is a world in which science gives us the power to annihilate ourselves.” The book concluded in an American classroom as students watch a video about what to do in the event of a nuclear attack.

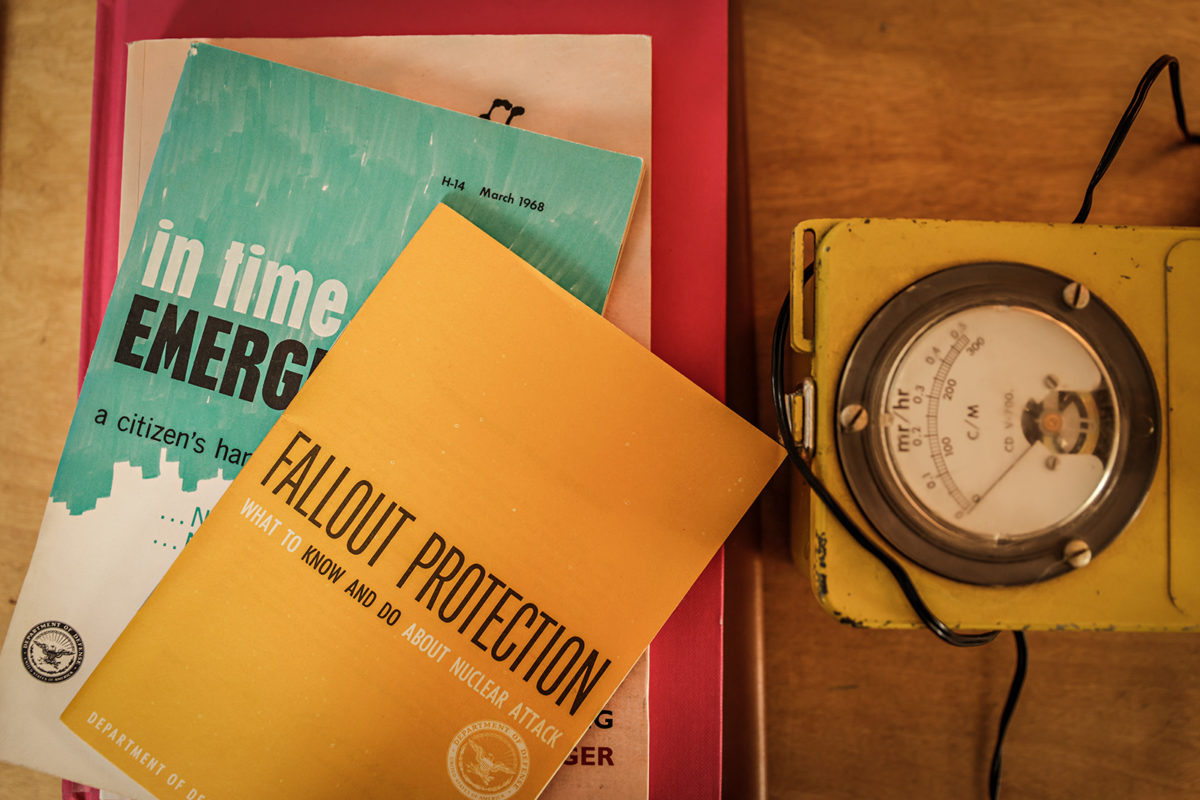

But Fetter-Vorm’s editor felt like there needed to be something more. Sitting around thinking about how to end the book, Fetter-Vorm remembered a road trip he took through the southwestern United States to observe nuclear test sites, including the Trinity site, for reference in illustrating the book. Joining him on the road trip was a 1950s Geiger Counter he bought online from someone in Pennsylvania. The small yellow box is connected by a chord to a metal wand that can be used to detect both the presence and intensity of radiation. The greater the radiation, the faster the Geiger counter emits a clicking noise.

Driving along in Arizona, Fetter-Vorm saw in the distance a pile of geometrically arranged stones protruding from the desert landscape. He pulled over and walked closer, until he could read a stone tablet saying this was once the site of a uranium mine. Nearby he could see wellheads with locked caps jutting from the ground like exposed piping. He brought is Geiger counter to a cap, and it began clicking rapidly. It was more radiation than he should have been exposed to in a year.

Fetter-Vorm’s ending for “Trinity” was there, on what he remembers as a beautiful, pristine day.

“Everything looks fine, everything’s great, but because I have this sensor I can see that there’s this cosmic, destructive force just emanating from the earth itself,” Fetter-Vorm said in a recent interview with the Beacon. Overlaid on the desert scene, the final lines of the book say this: “No smell or sound comes from below. There is nothing to see. But our senses fail us. If radiation were somehow visible…we would see this power everywhere we looked. We would see it in the rocks, in our bones, in the air and the water. We would see that the secret of atomic power was stolen not from the gods, but simply from the earth. And we would remember that this atomic force is a force of nature. As innocent as an earthquake. As oblivious as the sun. It will outlast our dreams.”

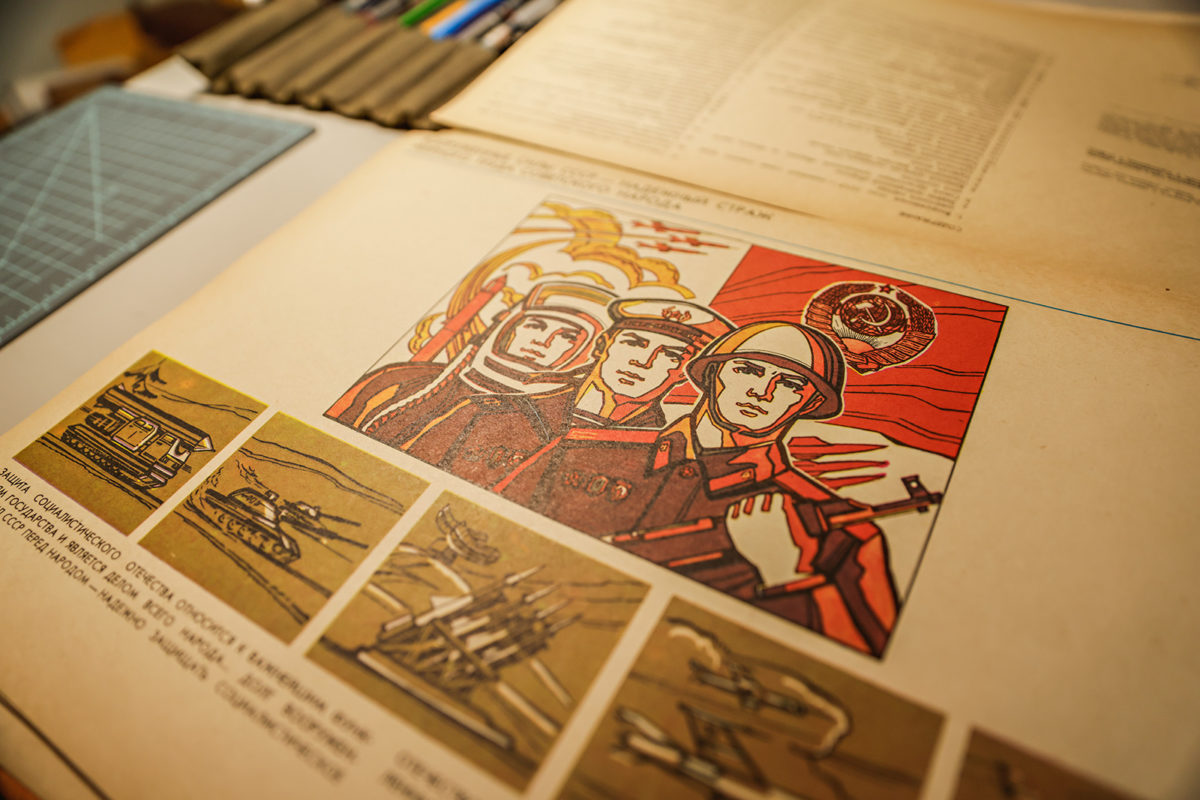

June will mark 10 years since “Trinity” was first published in 2012, and the anniversary comes at a time when the book that launched Fetter-Vorm’s career has taken on a renewed significance amid the threat of nuclear war brought on by Russia’s war against Ukraine and the efforts of the United States and NATO partners to support the Ukrainian military.

In the years since the publication of “Trinity,” Fetter-Vorm, 39, has published two more books, “Battle Lines: A Graphic History of the Civil War” and “Moonbound: Apollo 11 and the Dream of Spaceflight.” He’s also gotten married, become a father, and moved back to Montana from Brooklyn.

Recalling the initial impulse that pushed him toward beginning the book in 2009, Fetter-Vorm said that at the time he was interested in the fact that the story of the atomic bomb felt like distant history, and yet “once they built this bomb, even if we’re not paying attention to it, it’s still there.” He wanted to introduce this piece of history to a generation of people who had very little connection to it.

“It seems like it’s still relevant,” he said, adding later that “It’s very disturbing to see people talking about it (nuclear weapons), as if it’s like, a strategic thing, or let’s say a tactical thing, just a part of a functioning war.”

While the prospect of nuclear war represents an existential threat to humanity, it also has its own Montana ties. Montana is home to some of the 400 Minuteman III missiles that remain active across Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, Colorado and Nebraska, according to a recent Washington Post story. The story, called “The nuclear silo next door,” explores what it’s like for Fergus County rancher Ed Butcher to live with a launch site on his property. The Minuteman III is a nuclear intercontinental ballistic missile that is 60 feet long, weighs 79,432 pounds, and has an explosive power 20 times greater than the bomb that struck Hiroshima, according to The Post. The same story also notes that the federal government chose central Montana as a nuclear hot spot in the 1950s because of both its nearness to Russia and because the area could function as, according to expert terminology quoted in the story, a “nuclear sacrificial sponge,” in the event of a war.

Fetter-Vorm’s book makes no mention of Montana, but it does spend some time dwelling on the connections between the bomb and the American West, including to some degree how the science itself at times had an improvisatory quality that came “from the hip.” He also writes that the Manhattan Project echoed “an enduring American mythos: that with enough money, hard work, open space, and inventiveness, anything is possible.”

The remote location for bomb testing, like the New Mexican desert, also helped avoid questions, according to Fetter-Vorm.

The book was researched extensively and parts draw on Fetter-Vorm’s own family’s history. The Manhattan Project, which is what the American-led effort to develop the atomic bomb was called, was a massive undertaking involving tens of thousands of people working at different locations across the country. For security purposes many who worked on the project didn’t know what they were doing, including Fetter-Vorm’s grandparents. He said his grandfather was a welder at a project site in Hanford, Washington and only learned what he had helped create after reading in a newspaper about the bomb having been dropped on Hiroshima. His grandparents, who he described as pacificists, were horrified by the revelation.

Then there’s Fetter-Vorm’s mother Mary, who shows up in one of the final pages of the book among the children in a classroom watching videos about taking shelter during a nuclear attack. He said that she grew up in the 1950s near an Air Force base in California, and that she would grow so nervous at the sound of the sirens deployed during duck and cover drills that she would become physically ill. It got to the point where she would get a hall pass beforehand so that she could go to the nurse’s office before the drill started.

In trying to capture the horror of the bombing of Japanese cities, Fetter-Vorm said he wanted to avoid the overwhelming, visceral depictions of burn victims because it makes people want to look away. “I want to work against that impulse to avert our gaze, I want you to be able to stare clear-eyed at the full-effect of this thing,” he said. “What that means is not to show the full damage in its breadth, but to try to find visual metaphors and visual stand-ins.”

That strategy, which he described as a kind of oblique approach, drew from the work of the Japanese photographer Shomei Tomatsu, who documented postwar Japan. In particular, Fetter-Vorm pointed to a photograph of a melted glass wine bottle that looks so blistered and twisted after it was exposed to the nuclear blast in Nagasaki that it looks at first glance like a human body part. In showing the bombing of Nagasaki, Fetter-Vorm focuses at first on two Japanese boys riding their bicycles, talking about super powers and arguing over a girl. After the bomb drops the next page is almost completely white and decluttered. There is no text, just blackened silhouettes on a flattened plane.

In the early portion of “Trinity,” illustrations and detailed, clear descriptions are used to explain concepts like nuclear energy, nuclear fission, and the detonation mechanisms inside the early model nuclear bombs.

“There’s a degree when you’re talking about quantum physics, where it is just beyond our understanding, and certainly beyond my understanding,” Fetter-Vorm said. “I wanted to make it to come far enough that you could get an idea but not so far that it was accurate to cutting edge quantum mechanics, because I have no ability to do that.”

The process for getting there involved reaching out to physicists to see if the explanations were sound enough to not make them cringe when reading it, according to Fetter-Vorm.

“When I was wrestling with that, it sort of clarified for me a theme of the book, which is how to show something that is unseeable. How to look at something, whether it’s an atomic explosion, which you physiologically cannot look at because it would burn your eyes—you’ll go blind—or whether it’s this bizarre buzzing of subatomic particles that we can barely understand and certainly can’t look at,” Fetter-Vorm said. “That’s the problem with radiation, and that’s the problem with that pipe in the desert with the Geiger counter. This huge danger that we live with is something that we cannot see.”