When Ted Kaczynski, a domestic terrorist known as “The Unabomber,” was arrested in 1996 at his cabin in Lincoln, Jamie Gehring had just turned 16 and was staying with her mother in Atascadero, California.

She and her high school boyfriend were driving in his sports car when the sound of Alanis Morissette’s song “Ironic” was interrupted by a breaking news broadcast announcing that “The Unabomber” had been apprehended outside his cabin in Lincoln.

“My heart sank and the breath left my body,” Gehring wrote of that day. “My boyfriend and I looked at each other in disbelief.”

Gehring’s shock was driven by the fact that she knew Ted Kaczynski, known sometimes in her family as Teddy, or “the hermit.” Kaczynski was her neighbor back in Lincoln, Montana, where she grew up, and spent most of her summers after her parents split up. By the time he was arrested, Kaczynski had killed three people and injured 23 others.

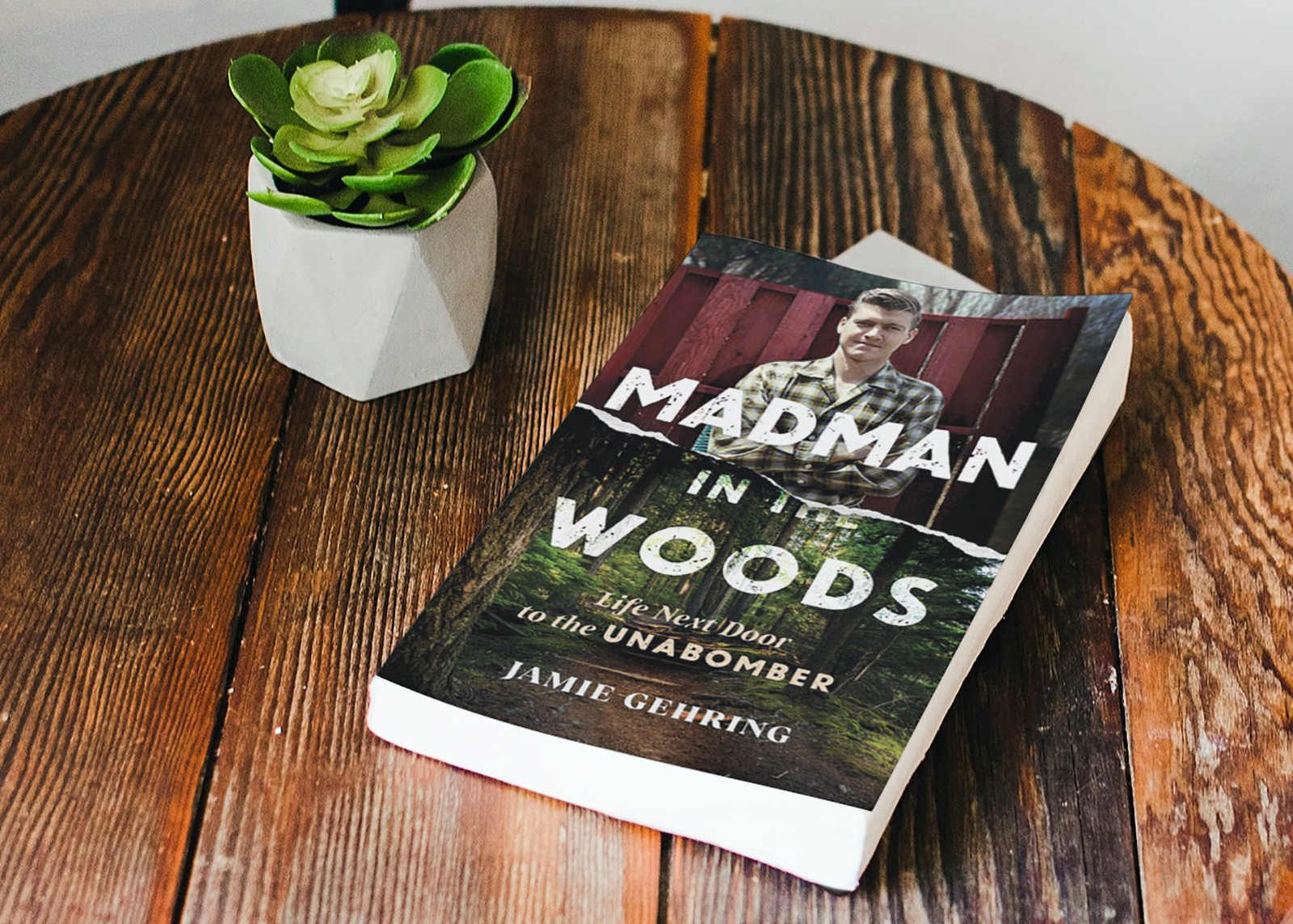

In her new book “Madman In The Woods: Life Next Door to the Unabomber,” Gehring chronicles her efforts to grapple with Kaczynski’s horrific crimes, and the way in which her own family’s story is intertwined, including ways in which her father, the local sawmill owner and former Green Beret Butch Gehring helped the FBI capture Kaczynski.

The story is told through a mixture of Jamie Gehring’s own memories of Kaczynski, as well as interviews with family members, local residents, archival research, and correspondence with people including FBI investigators, Kaczynski’s brother David, and Ted Kaczynski himself.

Gehring brings readers along and gives them a peek into her research and writing process, noting in the text of some chapters the conversations she had with sources who she allowed to review her writing and the commentary they offered. She also grapples with the horrors of what Kaczynski has done from her own perspective of a mother of three.

“There’s definitely additional content in this book, but I truly think it is a change in perspective that sets it apart,” Gehring said by phone from Denver, where she now lives.

Kaczynski purchased his parcel from Gehring’s family, and Jamie Gehring has early memories of him, including when he gave her a handmade cup as a gift. He also at one point asked to hold her when she was a baby, something that took place during a brief period where Kaczynski was invited to share meals with her family, and even play cards after dinner. Later he would show up and simply ask for the time and day, which began to increasingly unnerve her. In the book Gehring also makes the case for why she believes Kaczynski was likely behind the death of her beloved childhood dog, as well as other local dogs through the use of strychnine poison.

The book makes an effort to understand what could have set Kaczysnki on such a violent path, going so far as to even research a serious illness as an infant that led him to be hospitalized and separated from his family, as well as a controversial study he participated in at Harvard. She writes of his awkwardness around other people, and his unease as a student at Harvard University after he graduated from high school early. The book also delves into his failures with women, and the contradictions between his manifesto in which he railed against technology, his deeds and his journals.

It took about five years for the book to be completed, and Gehring said she had initially conceived of it as a book of short stories. “It just felt like it wasn’t personal enough,” she said. “I really wanted to explore how living next to Ted changed me, and our lives, and how our lives intersecting with his—how that looked and how that developed through the years.”

She continued, saying that writing the book allowed her to write about childhood memories in a way that felt powerful to her and gave her a sense of control over what she had gone through over the decades she’s spent trying to understand Kaczynski and what, if any effect her and her family had on his actions.

“When I was four and he delivered gifts to me, I trusted that he was an odd hermit, yet still a neighbor capable of tenderness. If my soft emotions toward Ted in those early years could be explained by his change in behavior and direction, then could I restore that small piece of my childhood innocence I lost when the truth surfaced about our neighbor?” Gehring writes. “Yes, I wanted a resolution to the mystery of the seemingly quiet time in the life of a murderer, but I also now understood what spurred my personal curiosity. I wanted to reclaim and justify my own blissful early childhood innocence. How innocent were those years?”

In one chapter titled “Couldn’t Be Ted,” Gehring goes from a deep dive into Kaczynski’s psychology, to a powerful recollection of her father Butch dying of cancer. The chapter then shifts into a look at how Kaczynski dealt with the death of his own father, and how Ted’s brother David Kaczynski has dealt with loss.

There’s also a chapter where sympathy for Kaczynski and his ideas falls away amid a parade of victim impact statements Gehring reviewed around Christmas time in 2019, and then excerpted for the book.

One of Kaczynski’s victims was Thomas Mosser, who opened up a bomb package in his home in 1994. He had a wife and four children. In the courtroom during his trial, Mosser’s wife Susan spoke about the pain Kaczynski had brought to her family by killing her husband.

“It was the worst day of my life, but only the beginning of the nightmare that is the Unabomber. My children are bleeding from their souls. Sometimes it is a pinprick. Sometimes it is a hemorrhage. To lose your father this way is unfathomable. And even three and a half years later we are still processing this horror. If it is processed all at once, you’d jump off a bridge. Every holiday has pain, every Father’s Day, every birthday, every graduation, every award. Every everything.”

“The experience shared here by Susan tore at my heart and soul,” Gehring writes. I felt any trace of clemency for my former neighbor fading.”