Underwater World

Diver and videographer Kyren Zimmerman is working with the Bigfork Art and Cultural Center to discover and document the history that lies underneath the surface of Flathead’s waterways

By Micah Drew

On May 9, 1937, one of the most luxurious ships on Flathead Lake caught fire and slipped beneath the surface just beyond Somers Bay.

Launched a decade earlier, the Kee-O-Mee was one of the finest boats on the Flathead, featuring four staterooms, a kitchen and a bathroom with a porcelain sink and tub. It even had hot and cold running water, a luxury in those days. The boat cost $12,000 to build (or about $164,000 in today’s dollars) and was named for the Blackfeet word for “far away.”

In the spring of 1937, owners John Sherman and Bert Saling upgraded the boat by adding a more powerful diesel engine. On one of the first voyages with the upgraded ship, the engine room caught fire. Sherman and Saling jumped in a lifeboat and rowed away as the Kee-O-Mee, engulfed in flames, burned down to the waterline before being lost to the waves.

Fast forward 80 years, when Kyren Zimmerman, a graduate of Flathead High School, and a group of local divers were recruited to search for the wreck of the fabled boat. Following several attempts to locate the wreck, including consulting historical sources on where it went down and conducting sonar scans of the possible areas, the team found the ship 64 feet under water, just past Somers Bay.

“The Kee-O-Mee was one of the first wreck sites that I dove on, and it was a completely unknown site until we found it,” Zimmerman said. “I was one of the first people to see that ship in over 100 years and the photographs are amazing.”

Zimmerman calls the Kee-O-Mee one of the “more charismatic wrecks” he’s dived on, due to its direct connection to the Flathead’s history. Sherman’s daughter, Dorothy, who passed away in 2019, was able to identify objects brought up from the wreck and share her memories of the day the boat sank with the dive team.

“Piecing history together like that is just amazing,” Zimmerman said. “People usually think of shipwrecks when they think of underwater archeology, but there’s a lot of really cool structures and materials left behind underwater. I mean, there’s kind of treasure everywhere if you know where to go.”

Zimmerman is currently teaming up with the Bigfork Art and Cultural Center (BACC) and the Bigfork History Project to complete an introductory archeological survey of the waterways in the Flathead and find some of those historical treasures. The goal is for Zimmerman and local historians to survey submerged sites around Flathead Lake, Flathead River, Swan Lake and Swan River.

“It helps us get a bigger picture of the things that are out there,” said Kyle Stetler, a board member with BACC and volunteer with the Bigfork History Project. “The things he’s finding under water aren’t the standard stuff you’d think about — boats and shipwrecks — but other facets of industry and the industrialization of the Flathead.”

Previously, Zimmerman worked with the Bigfork History Project, a brainchild of Ed Gillenwater and Danny Kellogg, on a documentary made back in 2016 and 2017. His skills as an underwater videographer were tapped to film a Northwest Dive and Recovery team salvaging logs from the Swan River that were left over from a 1914 Swan Lake timber sale.

Logs from the sale were floated down the Swan River and across the north end of Flathead Lake to the Somers mill, but it’s estimated that up to a quarter of the logs sank en route.

Zimmerman and other divers located many of the logs, some stacked 15-feet thick in deep holes in the Swan River, that were well preserved due to the low oxygen environment. The original brands of the logging companies can still be seen, and many logs are good enough quality to still be processed as lumber after divers raised them up to the surface.

“These might just be logs, but we at the Bigfork History Project recognize they’re part of the formative years of the Flathead,” Stetler said. “It’s part of the strong connection between the two sides of the lake, and it’s fun to see the history up close.”

Between diving for old logs, discovering the Kee-O-Mee and learning more about old wrecks, landing sites and other undiscovered stories from the Flathead, Zimmerman has literally dove headfirst into his work.

“I’m passionate about Bigfork history having grown up in the Valley, and I wanted to bring up new history with newer scientific collection techniques,” Zimmerman said. “I’m really trying to get us more connected, the public more connected, with our history on and under Flathead Lake.”

Zimmerman began diving in his early 20s and quickly found ways to combine his passion for underwater exploration with scientific research and education. He spent two years in New Zealand working with a fisheries crew to document changing river systems using time-lapse photography in the riverbeds.

“That really sparked my underwater filming career,” he said. “That was one of my highlight career projects, because we

actually got streamflow standards established on that river because of work we did scuba diving and taking photos.”

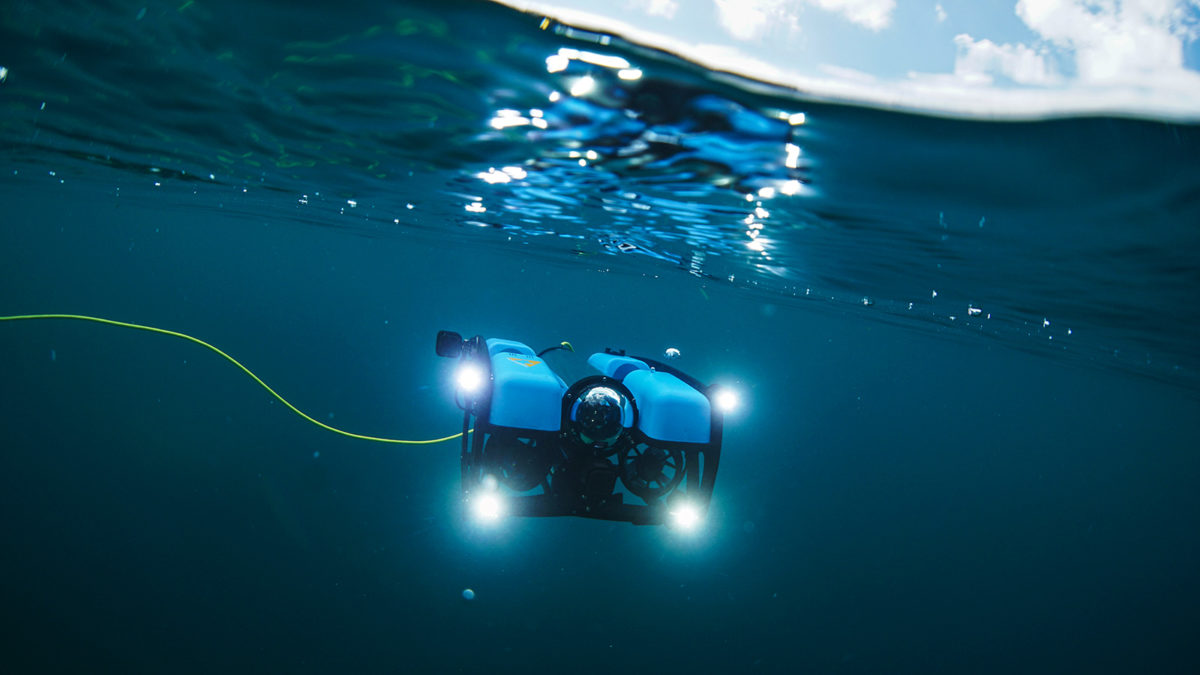

When he returned to Montana, Zimmerman worked on the logging documentary with the Bigfork History Project, helped Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks conduct fish surveys and expanded his underwater capabilities with a remotely operated vehicle, or ROV.

The blue ROV is roughly the size of a microwave and is maneuvered about using an Xbox controller. It can dive down to 300 feet and has four hours of operating time — far superior to a recreational human diver. Zimmerman has modified the ROV adding GPS systems to precisely track it while surveying sites and mounting additional cameras that allow him to capture comprehensive scans.

Zimmerman can take hundreds or thousands of photos of a site from all angles and run them through photogrammetry modeling software to generate a three-dimensional digital model.

“This opens up potential for survey sites like shipwrecks or Indigenous sites without disturbing the sites,” Zimmerman said. “If you’re diving on a site you can kick up sediment and disturb it even if you never touch anything.”

Zimmerman is taking the photo scanning technology to another level by 3D printing some of the renderings into intricately detailed physical models, allowing them to be displayed in exhibits and studied in detail above the surface.

“It’s the closest thing to a mirrored replica we can have without removing a piece,” he said.

One site Zimmerman has been searching for over the past months is tied to the same early logging operations on Swan Lake. Sometime in that period, some train cars supposedly overturned into the lake, but no one is sure where.

“Because they were so expensive, folks were pretty good about recovering rail cars, but we believe there’s still a car and some materials associated with it down there,” Zimmerman said.

Despite several interesting leads, Zimmerman’s dives have so far been fruitless, but each new version of a story he hears brings new possible locations to explore.

Minimal record keeping from decades and centuries past is one reason many underwater sites are difficult to find— a 1969 map that shows shipwrecks on Flathead Lake had the Kee-O-Mee marked “far from where we found it.”

Another is the fact that unlike terrestrial locations, underwater sites are often a jurisdictional gray area. Various local, state and federal agencies may have claims over waterways, but tend to be focused on the surface.

Ryan Powell, an archeologist with the Flathead National Forest, said that much of the work he does is driven by U.S. Forest Service actions on land.

“When there’s road building, trail building, things like that, we get called in to survey areas and make sure there’s nothing of cultural or historical significance in the way of a project,” Powell said. “Even though we know there’s probably lots of resources under the surfaces, there just aren’t many times I’ve thought, ‘I need to get under the water and look for something.’”

Jessica Bush, the state archeologist with the Montana Historical Society (MHS), the agency in charge of historical and cultural sites, says that waterways in Montana are a virtually untapped realm for archeology in the state.

“This kind of work is important because we know waterways are important to humans and to human history,” Bush said. “When we talk about waterways, that’s where you’re going to get history from the beginning of human habitation of Montana

all the way to about 70 years ago.”

“If you were a grad student looking for a research project, there’s so much that could be done here,” she added. “If you look at any of the reservoirs, which covered what used to be terrestrial sites, you could find everything from pre-contact all the way up to towns that were abandoned — railways, roads, you name it.”

The MHS maintains a database of all known historical and cultural sites in the state, adding to it anytime someone contacts them with a potential lead. When sites of historical significance, or suspected significance, are reported to the state, they are assigned a Smithsonian number, and if possible are surveyed by GIS specialists. The MHS database helps ensure that any future development doesn’t damage an area of significance.

The database is not searchable by the public, except for researchers and historians to keep an extra layer of protection over them, but Bush said that also adds to a misconception that the state controls these areas.

“I’m purely here for informational purposes and to help out,” Bush said. “From our point of view, we get into this job because we’re passionate about it, love it and want to protect this stuff for the future. We can’t protect sites if we don’t know about them.”

Bush says that, compared to states that are known for their maritime treasures, such as Florida or Minnesota, Montana has relatively vague laws surrounding underwater archeology and few people understand how much there is to be learned from such sites.

“To me, archeology is really exciting because it’s a check and balance to the historical documents,” she said. “You can read books and research history and find primary sources, but sometimes the archeology contradicts what’s been written down.”

To tie that into the Flathead, Bush said that records of men working in logging camps come mostly in the form of company documentation, which could prove biased and provide little insight on daily routines.

“If something as simple as a tobacco can was found at an old mill site underwater, that’s a huge insight into those lives,” she said. “It’s one of those things where knowledge is key.”

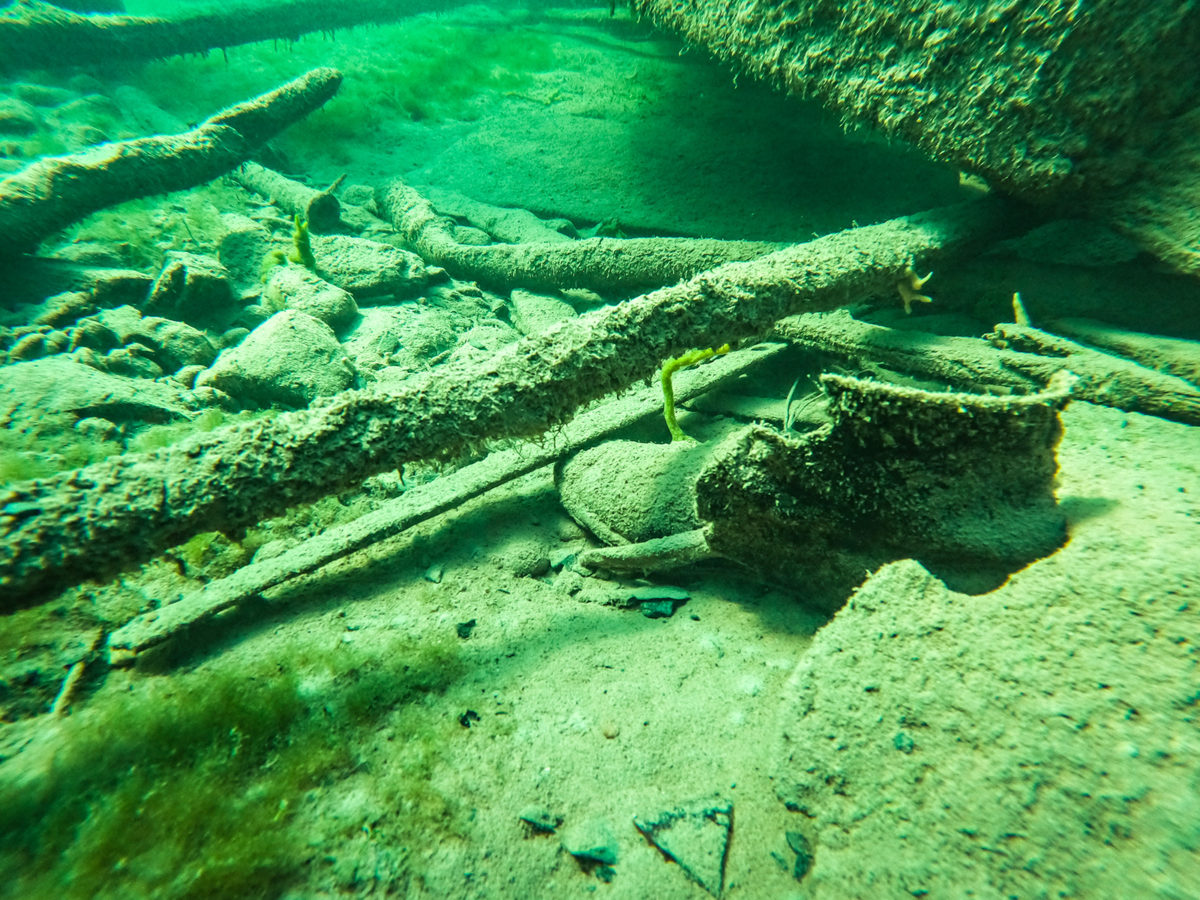

One site Zimmerman surveyed has a twin set of old rail wheels, and among the debris was an old leather boot.

“For me, that was a ‘wow’ moment because it’s the human component in all of this,” Zimmerman said. “What’s the story behind that boot?”

Zimmerman and Stetler said that, as long as funding is available, they want to keep exploring and documenting the underwater history around the Flathead. There are plans to visit the Demersville townsite along the Flathead River, look at old ferry crossings on the Flathead River and other steamboat landings on Flathead Lake. Most recently, Zimmerman surveyed stacks of old cars in the Flathead River that were used either as old forms of erosion control or just a private dumping ground. He also located an old wooden rowboat he estimates is from the early 1900s, and dove on an old, demolished bridge site on the Flathead River.

“I’m not the researcher here, I’m just the guy collecting the photos and documentation,” Zimmerman said. “But we can make it accessible to somebody who might know more — they might know a personal story attached to what we’ve found or have the historical knowledge to put it in perspective and make interpretations.”

The BACC will have an exhibit based on Zimmerman’s work beginning on Nov. 1, featuring photos and 3D models of some of his latest surveys.

“Providing this resource is something that can not only get people excited about revisiting our past with modern technologies but shows what can be achieved with this technology,” Zimmerman said. “I’d love to have these renders and photos available to other local museums in the future. We’re all telling the same story of our local history, and this is just another facet most people don’t get to see.”