The ‘Poster Child’ for Development Approval

Kalispell city planners have been mapping out the municipality’s growth for years, setting the council up to approve 5,000 units since 2018 - despite opposition - as the state tries to address the housing shortage

By Maggie Dresser

In August of 2021, the Kalispell City Council approved 400 units of housing near the Foys Lake interchange on a failed development property. In March of 2022, the council approved 600 housing units in between Two Mile Drive and Three Mile Drive. Two years earlier, it greenlit 144 apartment units on Meridian Court, which were recently constructed on the city’s west side.

Since 2018, Kalispell officials have approved about 5,000 housing units. Of those thousands of units, 905 are detached single-family homes, 678 are townhomes, 3,159 are multifamily units and one project encompasses 84 acres that will be used for mixed-use developments.

In the 24 years that Senior Planner PJ Sorensen has worked for the City of Kalispell, he says very few developments have been rejected, despite opposition from the public.

As the council continues to approve a variety of projects, members of the public have also continued to pack council chambers on Monday nights. While some development proposals are met with no opposition, other projects receive intense backlash from neighbors.

In early October, for example, Flathead residents ranging from business owners to nonprofit leaders to retirees filled the chambers to oppose an eight-story parking garage that will include 78 multifamily units. Those who spoke during public comment were primarily concerned about congestion and a departure from Kalispell’s “historic character.”

The city council approved the project in an 8-1 vote.

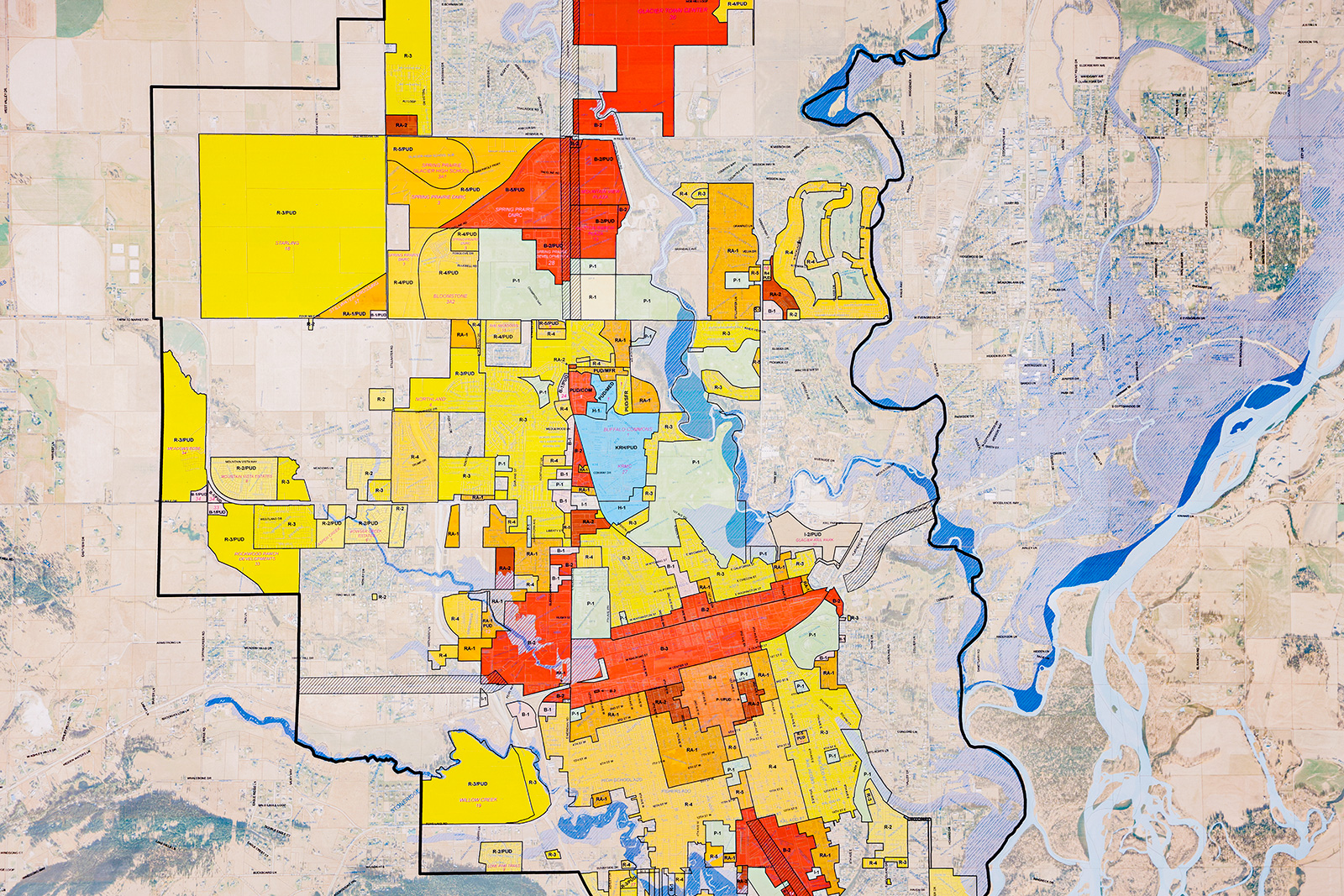

Planning Services Director Jarod Nygren and Sorensen say that although the projects may appear drastic and sudden to members of the general public, city officials have been laying plans to accommodate a high volume of development through implementation of its Growth Policy, which was updated in 2017. Surrounding the city’s downtown area, the policy establishes an annexation boundary and staff have been hard at work installing infrastructure like sewer, water and transportation updates for years to prepare for growth.

“I think it’s important that everywhere that the council approved a development, we knew a development was going to happen,” Nygren said. “We plan for it – so even if it’s a field, we plan for it to be residential … it’s not an afterthought, which makes it a little easier for council to make that decision because it’s in our urban growth boundary.”

Kalispell Mayor Mark Johnson, whose first term began in 2014, calls the Growth Policy the city’s “key guiding document;” if developers follow the criteria laid out in the policy, he says, the council will likely approve their proposal.

“I don’t know if other municipalities have as robust of a planning process – but we just take the approach of ‘here are the rules of the game,’” Johnson said.

Between 2020 and 2021, Flathead County grew by 3,700 residents, according to recent Montana Department of Labor and Industry data, and home prices increased 90% from August 2020 to August 2022. Officials say the rental vacancy rate hovers around 1%.

While other municipalities in the Flathead are also in desperate need of housing, cities like Whitefish and Columbia Falls do not have the same track record as Kalispell when it comes to adding to the housing supply.

In July, a developer pulled an application for a proposal that would have brought 455 units of housing to Columbia Falls after hundreds of residents showed up to a planning board meeting in opposition.

Earlier this year, the Whitefish City Council rejected the proposed 318-unit Arim Mountain Gateway Development that would have brought 270 rental apartments, 36 townhomes and 12 condos, some of which would have been deed-restricted. Traffic, emergency access and a change in community character were the main concerns of citizens who spoke during public comment.

But one of the loudest voices during the process came from local billionaire Mark Jones, who threatened to withhold future financial support for affordable housing if the development went through.

“People had different opinions about that project,” Whitefish Planning and Building Director David Taylor said. “We had a Wisconsin Avenue plan that called for workforce housing. People were concerned about traffic issues during ski season and that it was out of character, but it has been zoned for high density since the 80s.”

Taylor says he’s frustrated that large housing developments are often rejected, and he says he sees the same people attending city council meetings to oppose projects.

“We’ve had councilors call people out during meetings – it’s not unique to Whitefish, it’s everywhere,” Taylor said. “I think it’s a challenge – how do we educate people about the reason we need housing? It’s not just new people coming here, it’s people being displaced.”

Developers have also become frustrated as opponents rip apart their projects. In 2020, the city council rejected an affordable housing proposal that would have built 36 units near Muldown Elementary School through the Whitefish Housing Authority. After the proposal failed, a developer built high-end condos in its place, which Taylor says brings in the same amount of traffic that the failed project would have.

“That’s just an example of ‘be careful what you wish for,’” Taylor said.

Local developers like Mick Ruis and Bill Goldberg, who have historically built in Whitefish, have shifted their focus to Kalispell in recent years. Goldberg purchased the historic KM Building in Kalispell where his company, Compass Construction, is now headquartered.

Goldberg is also a partner in Montana Hotel Developers LLC and the developer behind the Charles Hotel, as well as an eight-story parking garage project. As such, he applauded Kalispell’s efforts at an October council meeting right before his project was approved.

“I want to thank you guys,” Goldberg said at the meeting. “Planning, city staff, council – thank you for the platform and the structure and the opportunity to have discussions so we can get to the table with projects like the Charles, like the parking garage and our multifamily (housing). I can assure you, it won’t be the last from our group.”

Kalispell city staff have been working to attract developers for years to bring more housing to the county seat while adding downtown vibrancy.

In 2020, the city council voted to lower impact fees for developers, which in turn raised water and sewer fees for property owners. The resolution was met with controversy as it went through council, but it still passed in a 6-3 vote.

Water impact fees, or one-time rates on new developments, dropped 50% and the city saw a record high number in building permits the following year. In 2021, 878 building permits were issued compared to 460 in 2020.

As soon as the impact fees were lowered, city staff noticed an increase in multifamily development proposals, likely because the city removed a financial barrier, which costs significantly more on larger developments.

In addition to a higher quantity of proposed units, the city is also seeing a wide range in housing types that are coming to council. While more than half of the units are multifamily, developers are approaching council with housing types that are not traditional to Montana, like rowhouses and cottages.

But as some community members support Kalispell for adding to the inventory, the city is frequently criticized for adding primarily market-rate housing to the supply, which remains out of reach to many prospective homeowners.

Last year, the council approved a 138-unit multifamily development called Junegrass Place on North Meridian Road, which was awarded $4.78 million in housing tax credits through the Montana Board of Housing. But most of the hundreds of building permits that have been issued will be at market rate, prompting nonprofit leaders to call on the city to do more to encourage deed-restricted housing.

Mayre Flowers of Citizens for a Better Flathead spoke in opposition of the parking garage development at multiple city council meetings, saying the city “missed an opportunity” when the project was approved. She would have preferred to see deed-restricted housing instead of an eight-story parking garage.

“I think there’s just no real basis to say that adding housing will address affordability in our state,” Flowers said. “Kalispell is probably the poster child for adding housing. The numbers that they have approved are pretty amazing, but most are not deed restricted and it’s encouraging people to move to the area without having housing for the workforce.”

In addition to affordability, Flowers has concerns that the Flathead will soon be stripped of its small-town character, while the addition of housing on the outskirts of town will erode its prized open space. But, while she’s opposed to urban sprawl, Flowers is also opposed to building vertical.

Ruis’ development at the former CHS grain elevator property on Center Street and Fifth Avenue West where the grain silos sit is already 100 feet tall. Crews are in the process of constructing a restaurant on top of the silos, along with 230 residential units on 5 acres.

“People say, ‘how can you change the character of a small town?’” Nygren said. “We’ve done a lot of planning efforts over the years and support increased height to get increased density. Going up rather than out is an easy way to put it.”

Last month, the Governor’s Housing Task Force submitted its final report to Gov. Greg Gianforte. It’s the product of a group formed in July to craft recommendations to add to the supply of “affordable and attainable workforce housing.”

Comprised of state legislators, economists, nonprofit leaders and local officials, the task force established a report that included solutions like reforming regulations, investing in “government efficiency” and streamlining permitting processes.

Kalispell City Manager Doug Russell said the municipality has already been adhering to many of the recommendations in the report, including approving high-density housing projects, facilitating growth and streamlining planned unit development (PUD) processes.

“We’ve already taken that approach,” Russell said. “We combine processes like annexation and zoning so we can get through the approval in a few months as opposed to a year-plus. We have already streamlined that process to get through that much quicker.”

But Russell is concerned that statewide policies could remove local control from individual municipalities, which all face different challenges and have unique needs.

Republican Sen. Greg Hertz, of Polson, who sat on the task force, said its goal was to open areas up for high-density development. He also hoped to lift restrictions like parking requirements, allow accessory dwelling units in all zones and to offer infrastructure grants to cities to incentivize growth.

Hertz would prefer to see decisions made at the local level, but he argues that officials aren’t doing anything to add to the supply.

“If you don’t actively make changes, the Legislature will come in and mandate,” Hertz said.

Mayor Johnson disagrees with the blanket approach of the housing task force, and he was disappointed nobody from Kalispell was invited to participate. The only Flathead-based members who served on the task force included Glacier Bank Market President Mike Smith and ShelterWF President and CEO Nathan Dugan.

“I looked at the makeup of that group and I was a little surprised,” Johnson said. “Kalispell has added more housing than any city in the state of Montana and we were never invited to the table. What I see happening will remove more of the rights of local government.”

As housing proposals continue to sail through the city council, and as members of the public continue to feel the growing pains, officials say a fear of change is an overarching theme. Common complaints include the transformation of farmlands into developments, eyesores of vertical growth and an increase in traffic and congestion.

“The valley is changing around them, especially for those that have been here a long time,” Nygren said. “It depends on who you are and where you’re coming from. But the reality is, the city’s growing, and it has to grow somewhere. The city accepted that a long time ago. And that’s why we have to plan for it.”

Although the city council is approving thousands of units, city staff say that doesn’t mean they will all get built. High construction costs, a tight labor pool and supply chain disruptions continue to slow down the pace of building, and some projects might not reach completion.

Nygren said 100 units in the city were supposed to come online in December, but the completion date has been delayed until next spring because the developer can’t find electrical panels or transformers.

“We planned for it, they’re approved, but they’re just not being built as fast right now,” Nygren said. “We’re a little opposite of some areas that hadn’t planned for it. They’re behind the eight ball as far as approving units and we’re ahead of it.”