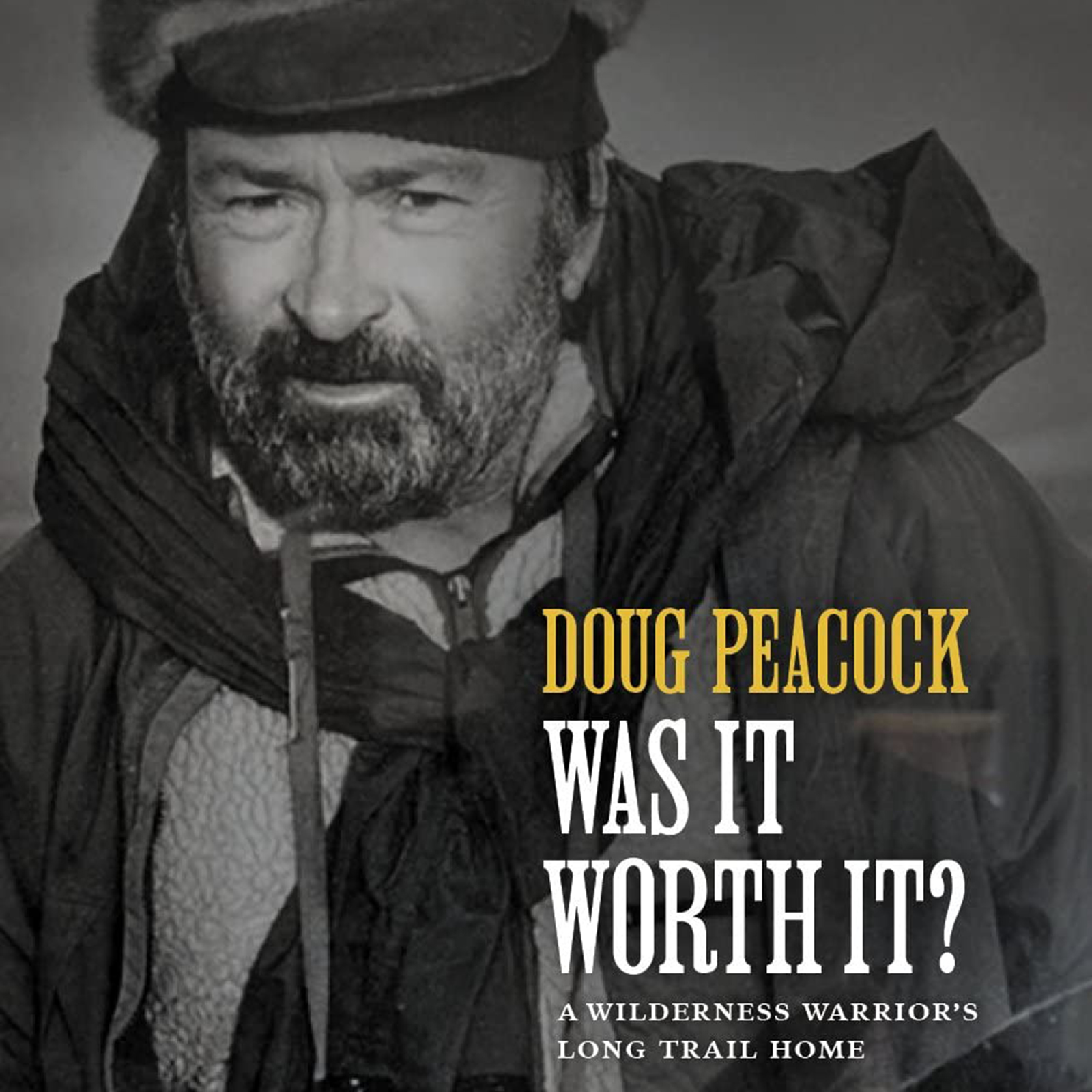

There is likely only one person who could elude the FBI in 1989 by slipping into a plywood McKenzie-style drift boat near Divide, Montana, and floating for weeks without detection until reaching the headwaters of the Missouri River at Three Forks. That person is Doug Peacock, writer, naturalist, filmmaker, conservation advocate, decorated Vietnam veteran, and the model for Edward Abbey’s iconic and eccentric wilderness warrior from the Monkey Wrench Gang, George Washington Hayduke. Peacock’s chronicle of his solo river journey on the Big Hole and Jefferson Rivers is one of many recollections shaping his latest book, Was It Worth It? A Wilderness Warrior’s Long Trail Home.

That specific trip was instigated by the death of his longtime friend, Abbey, and the Earth First! bust. While those circumstances would have been reason enough to hit the water, another aspect spurring the downstream dodge was the quest for “total anonymity for a few weeks. This had less to do with being on the lam from the FBI—who I doubted would try very hard to look for me, as I wasn’t that important—than it did with wanting a leisurely break from my own life for a bit.”

As the author of five previous books, including Grizzly Year: In Search of American Wilderness considered a classic of outdoor literature, Was It Worth It? is a collection of selected stories by Peacock to “fill the spaces between the infrequent books I’ve written.” These stories serve as Peacock’s own “winter count,” inspired by Plains tribes who marked important occurrences, such as a battle or extreme snowfall on the inner sides of a bison hide. Abbey’s death on March 14, 1989, whom Peacock describes as a “desert anarchist and writer,” was among the most significant.

Part recollection and part lament, Peacock plots thirteen continent-spanning adventure tales as a narrative version of painting bison hides. Richly detailed, Peacock writes about the origin of Hayduke, a character that shared his past as a war veteran and lover of the desert and its wildness. Included in this testament is his time in Yellowstone National Park following his two Vietnam tours as a Green Beret medic as well as a far-flung expedition to southeast Russia in 1992 with the “Do Boys.” Comprised of accomplished and notable figures, the Do Boys included Yvon Chouinard, Rick Ridgeway, Doug Tompkins, Jib Ellison, and Tom Brokaw. The chapter “Tiger Tales” recounts their trip in search of Siberian tigers and kayaking the Bikin River, a sport that Peacock admits he’s not especially adept at. Of his longtime friends Peacock writes, “What is perhaps most inviting about traveling with the Do Boys is less that they travel to exotic places for dangerous adventure than that they have genuine curiosity about the wide world, and all try, in their own remarkable ways, to beneficially affect its future.”

At the heart of this collection, even if it is steeped in past adventures from observing grizzlies in the Northern Rockies to roaming the desert Southwest, is the commitment to acting in ways that are beneficial to the environment and all its inhabitants. As he opines, “This was not the same as seeing the wilderness as a giant supermarket. For me, proper use of the wild implied that the wilderness—or the land, of even the planet, should get something back from our human use, a beneficial symbiosis.”

The theme of reciprocity in its various manifestations continues in “Reburying the Arrowheads.” Peacock travels to his native Michigan to return his boyhood collection of arrowheads, prehistoric tools, and knives, all relics he discovered near the Shiawassee River. The repatriation of Indigenous artifacts is also the story of how his boyhood explorations shaped him into the person he is today. “Gradually, this boyhood vision of adventure edged into the larger world,” he writes, “and I craved wildness beyond the woodlots and fallow fields; it launched a lifetime aimed at boundless horizons and decades spent chasing grizzlies, tigers, jaguars, and polar bears all over the Northern Hemisphere.” Returning the items to where he found them 50 years earlier was more important than donating them to a museum. Leary of “conventional archaeology,” Peacock wanted the arrowheads returned to the earth and “not in the musty drawers of some museum.”

It’s that solitude and wildness-induced possibilities that continue to inspire him, even though the threat of climate change looms large. As he implores in the book’s postscript, written during the COVID-19 global pandemic, “There is so much beauty in the world all we have to do is stick around to see it.” As an advocate for grizzly bears and wild landscapes for 50 years, Peacock’s expression of grief supplies direction. A man of action, he appeals to a species on the brink: “There’s plenty of work to do; do your job with decency and an open heart. Love your brothers and sisters in all actions, in all relationships. Speak the truth. Extend your innate empathy to distant tribes and strange animals. Arm yourself with friendship and love the Earth.”

The book’s narrative can be challenging, with its various jumps through time, but overall it is beautifully composed. In the end, Peacock reassures us that all his time venturing in far-flung places in the company and unwavering defense of bears or tigers or polar bears was more than worth it.