New Meteorological Station Delivers Real-time Climate Data to CSKT Bison Range

The first-of-its-kind Mesonet tower west of Montana’s Continental Divide gathers weather, soil-moisture and snowpack data to inform Tribes’ rangeland management and climate plans

By Tristan Scott

It’s been exactly one year since the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) reclaimed management control over a bison range that’s as much an icon of cultural resilience as it is an ecological treasure — a 19,000-acre swath of Flathead Indian Reservation land where blue camas and bitterroot intermingle with native bird species, elk, grizzly bears, bull trout, and, of course, its namesake herd of shaggy buffalo.

As tribal land and wildlife managers lay long-term plans to conserve the bison range for future generations, however, gaps in monitoring data and outdated instrumentation have limited their understanding of the effects of climate change on the region, as well as how to plan for and mitigate those consequences, which include drought and the spread of invasive weeds. So, when an opportunity arose to partner with the Montana Climate Office on a grant proposal to install a first-of-its-kind, research-grade meteorological station on the bison range, CSKT biologists jumped at the chance.

“We do have some weather stations on the bison range, but they’re old and out of date. They’re only compatible with one laptop and accessing the data was cumbersome, so this is an area where we’ve had very little monitoring capacity,” said Shannon Clairmont, CSKT’s lead range biologist.

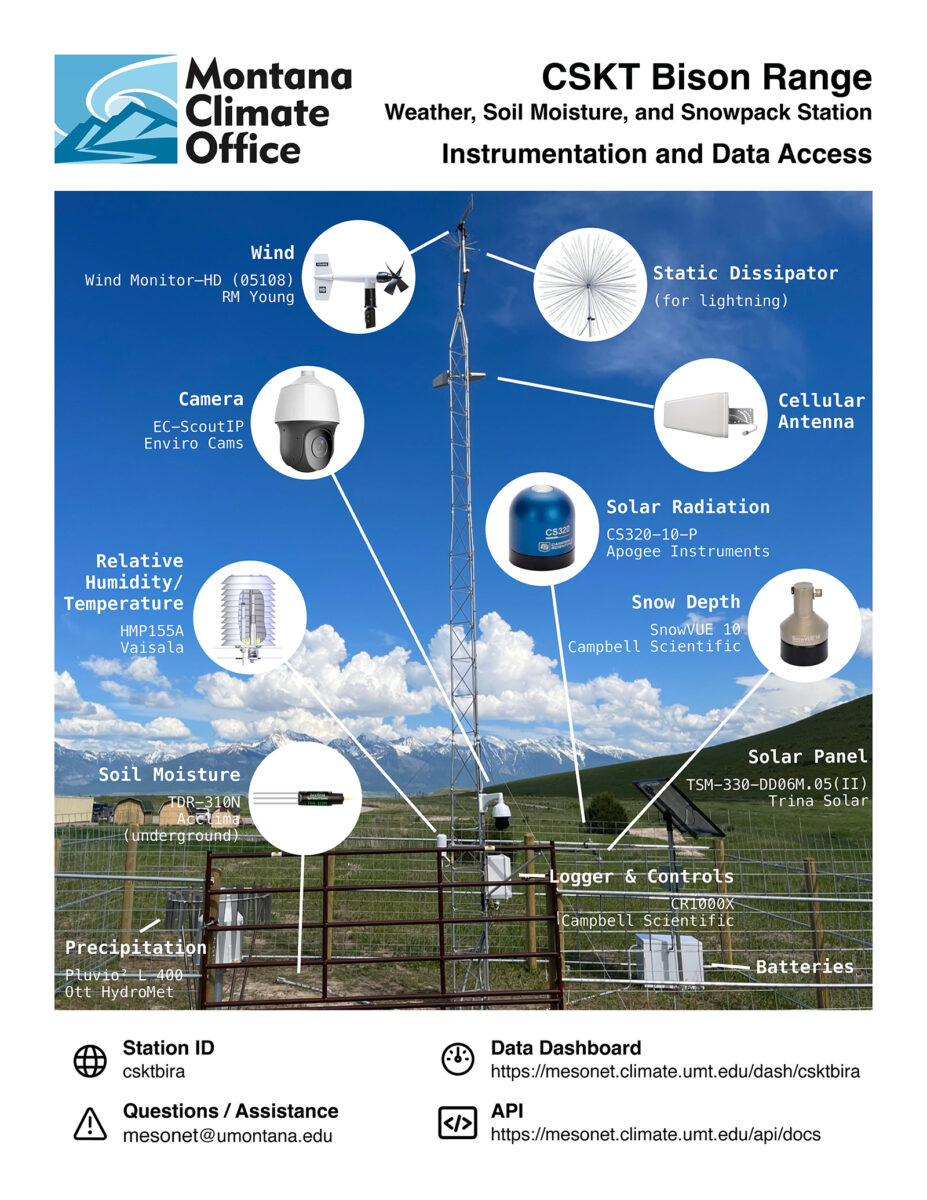

Funded by the Native Drought Resilience project through a grant by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Integrated Drought Information System, the new Mesonet Station records temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, solar radiation, soil moisture at depths down to a meter, and snow depth. Located behind the CSKT Bison Range Visitor Center, the automated environmental information is updated every five minutes and is installed on a 30-foot tower. It’s also self-contained, meaning it is powered through a solar panel and communicates via cellular connection, and the 20-by-30 footprint has no permanent concrete infrastructure, instead anchored by a large ground screw system.

According to Clairmont, the station will not only assist Bison Range managers and help meet CSKT’s climate resilience goals, but it will also help inform the surrounding valley residents with up-to-date information and planning for each year’s agricultural season.

“When the Montana Climate Office brought forward this proposal, it was kind of the perfect collaborative project to serve a lot of different needs in the valley,” Clairmont said. “It wraps together climate awareness and conservation on the bison range with land management and agribusiness needs across the reservation, and it helps us facilitate public education and outreach.”

In meteorology, a “mesonet” is a network of automated weather stations that are installed close enough to one other — and which report data frequently enough — to observe, measure and track. Although the Montana Climate Office has partnered with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to establish stations across eastern Montana and along the Missouri River Basin, this is the first such station west of the Continental Divide in the Columbia River Basin.

The monitoring data is available to both professional resource managers and interested valley producers via an internet portal (https://mesonet.climate.umt.edu/dash/).

Soon to come, educational signage will be placed on the walking path behind the CSKT Bison Range Visitor Center to explain what the station does and its importance for meeting the Tribes’ future planning goals.

Kyle Bocinsky, director of climate extension at the Montana Climate Office, which is an independent state-designated body at the University of Montana, said the need to expand monitoring in the region — and on the CSKT Bison Range in particular — has gained urgency in recent years. For example, as the CSKT revised its rangeland management plan while preparing to resume control over the bison range, which had been under the jurisdiction of the federal U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for more than a century, it was also completing an update to its Climate Change Strategic Plan.

Not only are the two plans closely linked, but the timing, Bocinsky said, couldn’t have been better.

“As the Tribes prepared to transfer ownership of the bison range, there was this growing need to expand localized monitoring capacity on the reservation for weather, soil moisture and snowpack to help assist rangeland managers like Shannon,” Bocinsky said. “When NOAA’s National Integrated Drought Information System put out a call for proposals looking at drought resiliency on tribal land and, specifically, for implementing actions that are specified in drought or climate adaptation plans, it really was a perfect fit.”

“In addition to expanding monitoring across the reservation, this will help build the next generation of climate leaders on the reservation,” he added.

The station will lend an advanced degree of sophistication to CSKT’s revised rangeland management plan by establishing a climatological baseline. It will also help sharpen the Tribes’ strategy for reseeding native grasses and identify environmental impacts related to the spread of invasive weeds.

“We’ve already found differences between existing [Natural Resource Conservation Survey] soil surveys and actual soil moisture availability based on the new monitoring,” Bocinsky said, explaining that the new monitoring equipment identified a layer of clay, or a lens, that was limiting soil-moisture availability to native bunch grasses, whose root systems were struggling to reach the deeper, wetter soil.

“Now we’ve figured out where that clay lens is located, how deep it is, and the range managers can take advantage of that knowledge when they’re reseeding native grasses,” Bocinsky said.

“As we think about the future in terms of climate on the bison range, this will help identify different strategies for improving that rangeland and maintaining it as a cultural asset,” Bocinsky added. “It’s just an honor for our office to be part of this.”