On a soggy September day, Steven Gnam and Mike Foote stood on the edge of a clearing, halfway up the trail to Granite Park Chalet in Glacier National Park.

They were staring at a dark shape protruding from the middle of a huckleberry patch.

“I’m thinking 75%, not a bear,” Gnam said. “But 25%, it’s a big thick guy just gorging itself.”

Moments earlier, hiking swiftly upward through a light layer of mist, Gnam had been reciting the difficulties of photographing glaciers during stormy weather when he spotted the dark form out of the corner of his eye and stopped mid-monologue. Peak huckleberry season in the alpine is ripe for grizzly encounters — the duo had already come across several in the last week, one which led to a dropped can of bear spray that burst, coating their gear — as well as a third companion, Jenn Lichter — in a patina of pepper.

During this day’s outing, Lichter was taking a brief respite from the group’s 12-day trek across the park to visit a physical therapist in Whitefish to assess an achy knee. The three ultra-runners — North Face-sponsored trail runners Foote and Lichter and adventure photographer Gnam — comprised an expedition attempting to reach all remaining named glaciers in the eponymous national park on foot.

While down an expedition member, Foote and Gnam had a schedule to keep, which today involved trekking from The Loop along Going-to the-Sun Road, past Granite Park to the Grinnell Overlook on the Continental Divide, descending the eastern slope of the ridge to visit Salamander and Grinnell glaciers, climbing back up and over Grinnell Point to the Swiftcurrent Glacier and returning to rendezvous with Lichter at Granite Park in time to put in a few trail miles to reach their intended camp.

But first, Gnam and Foote had to determine whether to prepare for another grizzly encounter. Several loud shouts and cautious steps circumventing the clearing indicated they’d paused over a bear-like boulder. With that resolved, the two resumed their swift ascent up the trail.

While Gnam didn’t capture this private moment on camera, much of the group’s travel, including other ursine encounters, was thoroughly documented and can be seen in the film “Shining Mountains,” which was released on May 19.

The 17-minute film, produced by The North Face in partnership with Protect Our Winters, follows Foote, Gnam and Lichter on a visual and emotional journey as they traverse Glacier National Park to reach its remaining named glaciers on foot. The adventure was part personal journey, part scientific endeavor and part awareness campaign.

All three expedition members have extensive histories with Glacier and its namesake ice masses. Gnam grew up in Whitefish and built a career photographing Glacier’s alpine flora and fauna. Foote has lived in western Montana for decades, previously worked as a guide in the park and has crossed vast swaths of it on foot. Lichter moved to Whitefish in 2019 and worked as a hiking guide in Glacier for several summers, telling visitors the story of how the ice carved the jagged mountains and valleys.

“As someone who’s been to Glacier many times, to see it in its raw form like this was powerful,” Lichter said. “It if weren’t for the glaciers, we wouldn’t have the park how it is today. Without the glaciers, there’d be no history.”

The 12-day expedition was Lichter’s first major backcountry trip, and one that humbled the two-time member of the U.S. National Mountain Running Team. “It wasn’t a polished experience for me. I gave it everything I had to be able to experience it that way,” she said. “I gained a whole new appreciation for what this land is. It just strips you down to pure emotion and true self … it made me better able to tell the story of Glacier.”

Lichter figures into the film as a lighthearted presence, offering off-the-cuff exclamations at the landscape and causing regular bouts of laughter among her companions, which gives levity to an otherwise heavy subject matter.

Stories about climate change and melting glaciers are often “doom-and-gloom clickbait,” Gnam said on the ascent up to Grinnell Overlook. “Because of Glacier’s name, people have this assumption about what’s in the park, maybe just a little out of sight. But there isn’t really any great media about it that shows the impact and presents it in a consumable, artistic way.”

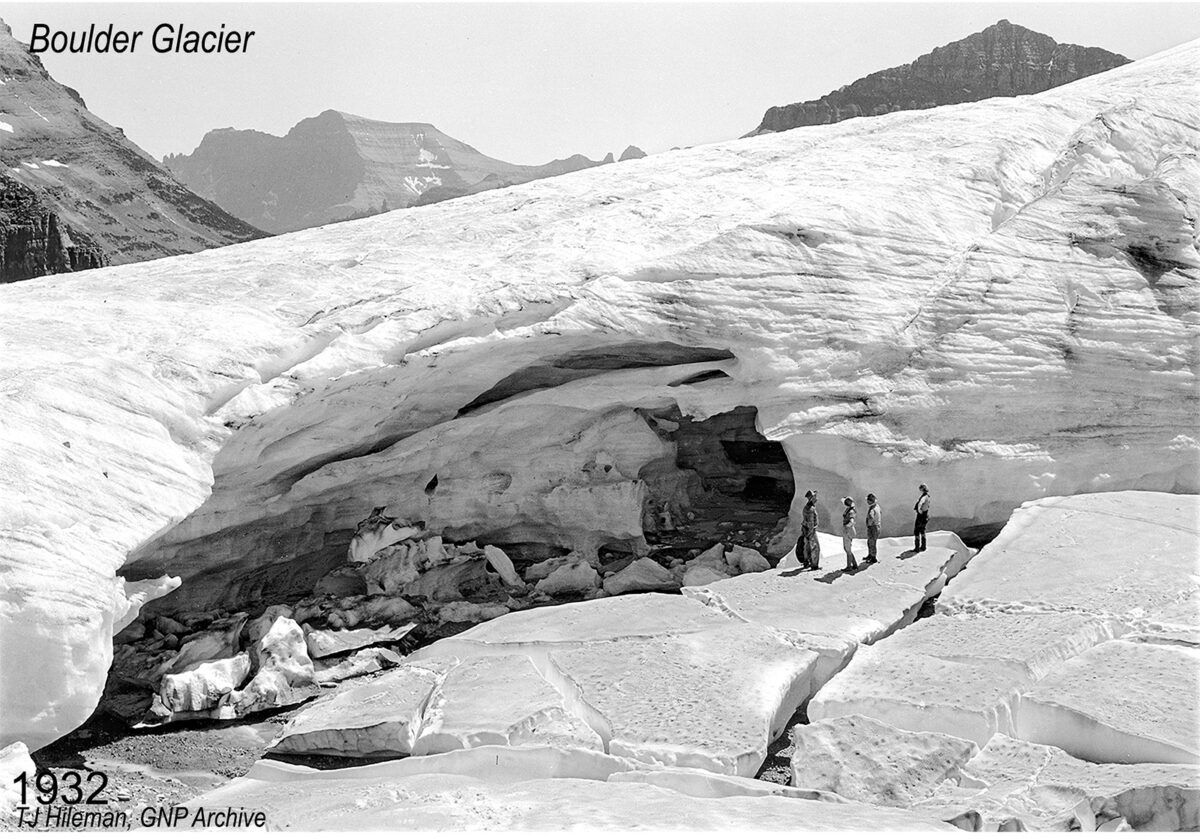

The best way to track the recession of the park’s glaciers is by looking at the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Repeat Photography Project, in which researchers have documented the icy landscape for more than 130 years. The extensive valley glaciers that carved the park’s majestic peaks reached maximum size around 1850, when there were more than 150 glaciers. Since then, the number of glaciers in the park has significantly decreased, with only 26 named ice fields remaining, all greatly diminished.

The Repeat Photography Project juxtaposes a sequence of historic photos taken between the late 1800s and early 1900s with more recent images captured by researchers who began visiting the same vantage points beginning in 1997. While some of the park’s glaciers, such as Grinnell, are easily accessed by trails, many require multi-day backcountry travel — not every scientist’s forte.

That kind of job calls for three of the region’s top mountain athletes.

“I know the park pretty well but trying to figure out how to access these places was still daunting,” said Foote, for whom the concept of such a mission-driven expedition had been percolating in his mind for years. “Some of these glaciers have receded so far back into the wild recesses of the park, it’s unlikely they’d been visited in decades.”

The route to the glaciers covered nearly 150 miles, much of it off-trail, and included roughly 50,000 vertical feet of climbing — a task conceivable only to experienced mountain runners.

“Having a certain skillset and being familiar with that kind of adversity in the backcountry, but also how to manage the challenges that arise and know when to adjust plans was a big asset,” Foote said. “Being an ultrarunner lends itself to long days of slow travel through complex terrain, and the ability to get up and do it again and again and again, which was the heart of this trip. We all have a certain comfort to that kind of adversity. “

At each of the glaciers the team reached, Gnam pulled out an old black-and-white USGS photo and held it up against the landscape, directing Lichter or Foote to move a few steps back and forth until the view in his camera frame matched the print. In some instances, acres of rocky terrain once covered by yards of impenetrable ice were stripped bare.

The glaciers are a “physical manifestation of the climate lying on the landscape,” said Dan Fagre, the former climate change research coordinator for the USGS Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center in Glacier.

If Glacier’s signature masses of snow are, as Fagre puts it, “a checking account for the climate,” then he’s the leading economist. As one of the foremost climate change scientists in the U.S., Fagre led the repeat-photo project for more than 25 years before retiring. Appearing throughout the film, Fagre said the key element linking his project to the North Face expedition is that “seeing is believing.”

“This is why we’re raising awareness,” Lichter says in a voiceover of a shot of the now-vanished Boulder Glacier. “So that hopefully not all of these will end up like [Boulder]. It was just sad. It was nothing man, nothing.”

To complement the photography project and the film, the expedition also envisions creating a multimedia exhibit to tell a more comprehensive story of the changing landscape. At each glacier, the mountain runners collected meltwater samples, filmed conversations inside of ice caves (“I felt like I was being hugged by the glacier,” Lichter quips) and painted the landscapes they traversed.

“One of our goals is to build an intimate, immersive, sensory experience so that the non-mountain traveler can better understand what exactly the glaciers are like,” Gnam said. “Because of Glacier’s name, people have this assumption about what’s there; we want them to understand that might not be the case much longer.”

“Shining Mountains” also brings in the voice of Tyrel Fenner, a hydrologist with the Blackfeet Nation, who talks about how Glacier National Park figures into the tribe’s creation story. Knitting together a range of voices from tribal stewards and scientific researchers was a key element of the project for the three runners, who didn’t want the film to dwell on the physical feat.

“It was always about the landscape and telling the stories around it,” Foote said. “We set out to be really intentional with this trip. This is not breaking news, that glaciers are melting. And I think despair can lead to apathy, whereas joy, engagement and connecting with places leads to caring about them and taking action.”

“Shining Mountains” doesn’t gloss over the messy parts of a mountainous expedition — Lichter’s injury forced her to skip the daytrip to Grinnell and the group tangled with multiple re-routes due to challenging terrain, bad weather and unplanned cameos by local grizzly bears — but those setbacks helped texturize a tale about melting ice into a nuanced homage to the Crown of the Continent.

At one point in the film, Foote jokes that the team wasn’t sure if their trip was a eulogy or a love letter.

“It’s important to share a story that’s all of the above — silliness, joy, what it means to love a place while also acknowledging there’s change,” he said. “I hope that this film helps people think about the places they think they belong and what they can do to care for them.”