In the Flathead Valley, the Homeless Crisis is at a Crossroads

The violent death of 60-year-old Scott Bryan forced a reckoning in the northwest Montana community, where the loss of critical mental health resources has intensified the plight of unsheltered individuals

By Maggie Dresser

When Kalispell Police Department (KPD) officers found Scott Bryan in the parking lot of a Conoco gas station in the middle of the night on June 25, he was lying face down, he was covered in blood and his nasal cavity was crushed. The frail, 60-year-old homeless man who was battling cancer and a variety of other health conditions had, allegedly, just been beaten into unconsciousness by a Kalispell teenager. He was pronounced dead at the hospital less than an hour later.

A witness at the scene of the Appleway Conoco gas station on Meridian Road showed officers an 8-second video that had already circulated on social media. In it, 19-year-old Kaleb Fleck and 18-year-old Wiley Meeker, appear at the scene of the assault that had just happened, with Bryan’s motionless body lying in the background.

Fleck and Meeker were arrested that night on deliberate homicide charges. Meeker was released from the Flathead County Detention Center two days later and would not see charges filed against him. Fleck was charged with a felony count of deliberate homicide. He was in jail for 10 days before he posted a $500,000 bond and was released.

A vigil was held shortly after Bryan’s death followed by a July 10 memorial service at the Flathead Warming Center that was attended by nonprofit leaders, neighbors and members of the homeless community. Attendees shared memories of Bryan but also called for support and an end to violence.

“He was our neighbor,” Sean Patrick O’Neill of Community Action Partnership of Northwest Montana (CAPNM), a social services resource in Kalispell, told a small crowd at Bryan’s memorial. “He touched a lot of people’s hearts whether they wanted to give their ear to him or not and he made a lot of friends along the way. But he was a frail man these last few months and years. He was not deserving of whatever happened to him on his last day.”

Social workers, law enforcement officers and community members have confirmed that the unprompted aggression against Bryan before he died mirrors a trend in Kalispell that has escalated in recent months. Stories of motorists running down pedestrians in parking lots, of lit firecrackers tossed into cars occupied by sleeping people and of teenagers harassing homeless tent encampments in the middle of the night have become increasingly common.

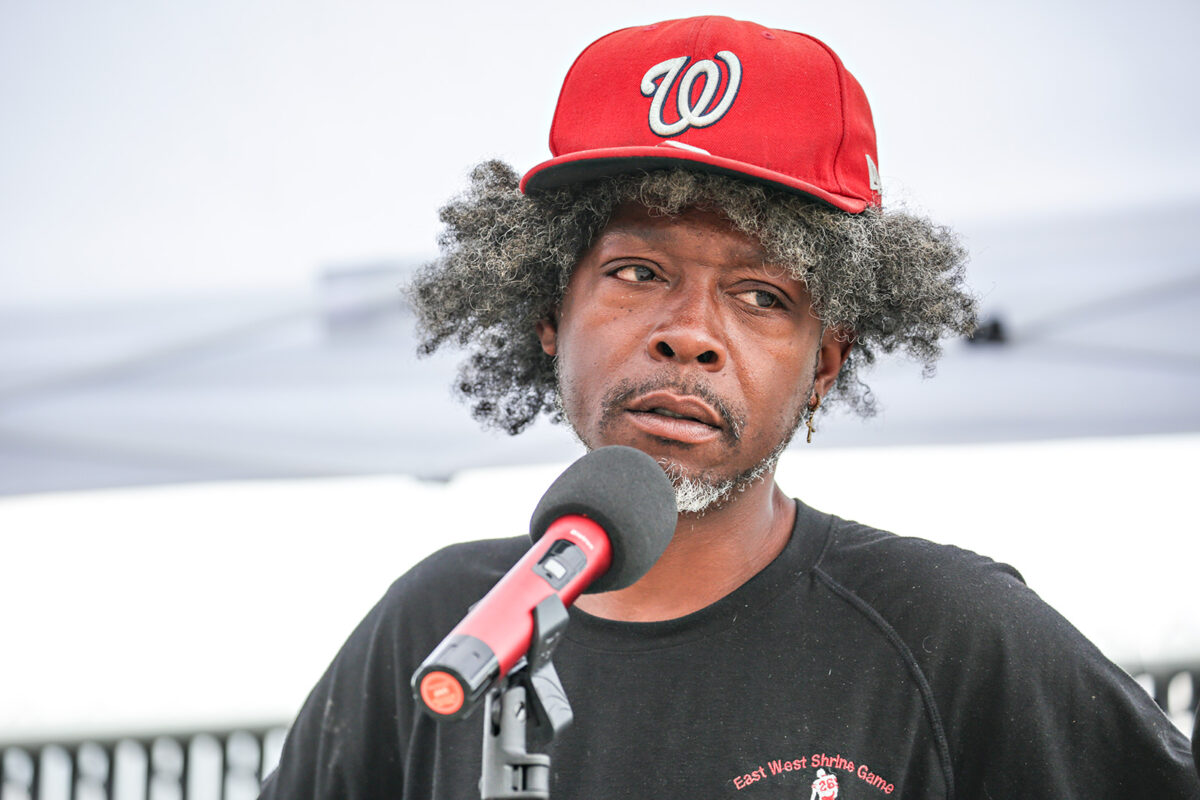

Jesse Green, a homeless man in Kalispell who spoke at Bryan’s service, said people frequently harass him and his unsheltered neighbors.

“They’ll tell us collectively to get the [expletive] out of here, to go back to California,” Green said. “I get really mad at that – I’m from D.C. They say, ‘Go get a job.’ Twice somebody said, ‘Why don’t you just die?’”

Kalispell Police Chief Jordan Venezio said his department frequently receives reports of harassment and assaults targeting the homeless population. While there are some active cases, Venezio said there’s usually not much that can be done to hold people accountable.

“We get a lot of questions regarding our response,” Venezio said. “Anytime we get those complaints, we investigate. If there’s evidence or leads, we do investigate and we have several active cases. But a lot of the reports being made don’t have enough of the facts or evidence available.”

At the Flathead Warming Center, a low-barrier shelter in Kalispell, Executive Director Tonya Horn works with some of the most vulnerable members of the community who suffer from mental illness, cognitive delays and physical disabilities.

Horn encourages her clients to report incidents to the police, but in many cases they are unable to provide identifying information about their assailants, which results in a further lack of accountability.

Horn said she and other nonprofit leaders now tell them to stick together instead of dispersing on their own to stay under the radar – a tactic they once advised.

“We tell them to stay together, but that’s opposite of what the community wants to see,” Horn said. “The community is seeing them together and it’s scary and alarming to them. However, that’s what they need to do for their safety.”

O’Neill has begun instructing his clients to adopt similar safety strategies, and he says many people are anxious about the potential for future assaults.

“They say they’re scared and they’re ready and prepared if they need to defend themselves – which is even scarier,” O’Neill said. “Now, they’re on high alert. They were already in fight-or-flight mode and now their senses are even more heightened to this.”

In recent years, Flathead County’s unhoused population has visibly grown as mental health services shrink, high housing costs have priced renters out of their homes, and long-term stay hotels like the FairBridge Inn and the Blue and White Motel have closed.

According to the MT Continuum of Care Coalition Point-in-Time (PIT) data collected in 2022, an estimated 319 homeless people were living in Kalispell, ranking a close second in the state behind the 325 homeless people reported living in Missoula, which has three times the population of Kalispell. Experts note that, while PIT data offers the most accurate tracking input available, quantifying homeless population figures presents numerous challenges since not every unsheltered person can be located to take the survey.

In the greater Kalispell area, there were 87 chronically homeless people in 2022, which HUD defines as someone who has been homeless for at least 12 months, on at least four separate occasions in a year, or someone who has a disabling condition.

By comparison, there were 22 chronically homeless individuals in the Kalispell area in 2020, according to PIT data.

“Two years ago, I could have told you every unsheltered person on the street,” O’Neill said. “But we’re talking about 100-plus people that are now on the street, according to our Point-in-Time survey.”

While there are a wide range of factors that can force people into homelessness, many social workers point to what they describe as a pivotal moment in Montana’s recent legislative history that caused a surge of people on the streets — the steep funding cuts to mental healthcare enacted during a 2017 special session of the Montana Legislature, when more than $50 million was cut from the Department of Health and Human Services’ (DPHHS) budget.

Specifically, the loss of the Case Management for Adults and Children program was a devastating blow to the most vulnerable populations, experts say, including those who needed individualized assistance with basic necessities like medical care, food and housing. Without one-on-one attention, many high-needs clients fell into crisis.

Almost two years ago, a five-bedroom crisis stabilization facility at the Western Montana Mental Health Center (WMMHC) known as the Glacier House in Kalispell closed due to a staffing shortage; earlier this year, officials announced it would not reopen. In February, Sunburst Mental Health in south Kalispell closed its doors after years of underfunding and allegations of Medicaid fraud.

“There’s nowhere for people to go to stabilize when they hit that mental health crisis,” Horn said.

When people do experience a mental health crisis, they are often sent to the emergency room at Logan Health. But Horn says patients are usually discharged shortly after they are admitted, and they wind up back on the streets.

“We’ll have someone at the Warming Center who is having a mental health crisis and we can’t help them,” Horn said. “We call the police, the police come but they don’t have the resources either.”

With nowhere to send people who are experiencing a mental health crisis, that crisis has become visible in public places like Depot, Woodland and Lawrence parks in Kalispell, as well as at local businesses, where police officers respond to calls ranging from trespassing to fentanyl overdoses.

Earlier this year, unhoused people drew attention when they began congregating in the gazebo at Depot Park. The structure provided shelter and a place to go for many folks, but after trash and human waste began accumulating at the park, members of the public began complaining to Kalispell city officials.

Reports of nudity, criminal activity, and drug and alcohol use at the park prompted the city to temporarily close the gazebo until the council passed ordinances limiting the use of the structure. The ordinances passed in February prohibit personal items in the gazebo, ban tents from being set up in the parks and establish time limits for occupying covered structures. The city also removed picnic tables from the park, threatened to turn off water spigots and considered installing a bar on park benches to prevent people from sleeping on them.

The activity also caused the Kalispell Chamber of Commerce to relocate its office in June, which bordered Depot Park. President and CEO Lorraine Clarno said that the disturbances prompted her to call the KPD for assistance on a daily basis.

Chief Venezio says the uptick in calls has kept KPD busy. But he also says their responses usually don’t offer any long-term solutions. Most calls involving transients are trespassing- or drug-related complaints, in which case his department is equipped to treat the symptoms but not the root of the problem.

“They just get moved along,” Venezio said.

Venezio said trespassing calls have tripled in recent years and his patrol officers usually respond to calls involving the same individuals – most of whom are suffering from mental illness or drug addiction. His department receives a slew of requests for welfare checks that often involve fentanyl overdoses, which is something he’s seen a spike in. Most members of the homeless population, he said, never come into contact with KPD.

According to KPD data, welfare checks spiked from 815 in 2019 to 1,263 in 2022, while disorderly conduct calls rose from 434 in 2019 to 696 in 2022. Venezio said the year-to-year growth has generally been steady, with the largest jump in 2021.

Additionally, a community crisis co-responder, shared between city and county departments, has also accompanied law enforcement on a steady stream of calls, responding to 21 calls for service in 12 shifts this July alone.

Discussions about the ordinances at city council meetings touched off a heated debate between homeless advocates and community members who were in support of the new rules last winter. But an open letter written by Flathead County Commissioners Pam Holmquist, Randy Brodehl and Brad Abell, entitled “Stop Enabling Homeless Population,” which was published in several local media outlets, ramped up the controversy to another level.

In the letter, the elected officials wrote that service providers were enabling the homeless community and causing a growth in homelessness. They also wrote that unhoused people are part of a “progressive networked community who have made the decision to reject help and live unmoored.”

The letter prompted intense backlash from nonprofit directors, who said it contributed to a negative community-wide rhetoric targeting unhoused people and has invited harassment and violence toward them.

“The county commissioners and that statement has created a platform,” Horn said. “It painted a picture that people are not from here, and we shouldn’t take care of them – it dehumanized them. There’s a lot of judgement happening with that and then people take it too far and we end up with violence and deaths.”

Along similar lines, attorneys for a transient man convicted of fatally shooting an employee at a Kalispell fitness center parking lot in 2021 while wounding another, argued their client couldn’t receive a fair trial in Kalispell. In their motion for a new trial venue, the lawyers referenced the commissioner’s letter and the negative sentiment toward the homeless population.

“It can be assumed the Commission’s collective condemnation can be seen as reflective of a broader community bias against the Defendant and those deemed to be transient,” the motion stated.

District Court Judge Dan Wilson denied the motion shortly before the trial began and a Flathead County jury last month convicted the defendant, Johnathan Shaw, of a felony count of deliberate homicide and attempted deliberate homicide.

Despite the consensus among homeless advocates, social services providers and public defenders that the rhetoric was problematic, county commissioners stood by their statement months later.

Commissioner Brodehl told the Beacon in July that while he acknowledges there are some homeless folks who have not chosen their lifestyle, he is convinced that many of them live unsheltered by choice, and they don’t deserve “handouts.”

“We were targeting the people who are the more transient population – people who are not participating in our community,” Brodehl said. “These are people looking for services but not looking for a way out.”

“I continue to support the letter we sent out in February, and I think it has had a very positive impact on what we have seen in our valley,” Brodehl added.

Commissioner Brad Abell also defended the letter, and said he felt it has been misrepresented.

Abell told the Beacon that he wants to help connect people to job services, but he doesn’t believe it’s the government’s responsibility to secure housing for anyone.

“I’d like to see more people getting instruction on how to rise out of the poverty that drives them into being homeless,” Abell said.

Green, the homeless man who spoke during Bryan’s memorial service, said he remembers when the commissioners’ letter was published last winter, and believes the physical aggression toward members of the homeless population began around that same time.

Originally from Washington, D.C., Green moved to the Flathead in 2012 to be with his foster family following a disabling injury that left him unable to continue working as a truck driver. He has lived on-and-off in the valley ever since, even after his family left the area.

“This was my only family unit – my only family support system,” Green said. “That’s how I ended up here.”

In D.C., Green was abandoned by his biological mother and his father was fatally shot when he was young. He bounced around in group and alternative homes as he grew up, and he was eventually connected with a foster family, with whom he stayed in touch through adulthood.

Years later, Green fathered a child in the Flathead during one of his stints in the region, which he described as the reason he came back even after his foster parents left.

“I’ve had housing here, but it’s gotten to the point where it’s just so expensive even with a job,” Green said. “What can I do? It’s just too expensive here.”

Horn says that a lot of her clients at the Warming Center report having experienced similar trauma in their lives, which has led to mental illness and suffering. Many of her clients are veterans, suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and have lost loved ones, she said.

“If you didn’t experience trauma before, you definitely experience trauma during homelessness,” Flathead Warming Center Operations Manager Audrey Tri said.

A combination of addiction and a spike in rent prices is what lead 31-year-old Jacob Buck into his current state of homelessness. A year-and-a-half ago, when Buck’s landlord kicked him out of his studio apartment so he could turn it into a short-term rental, he moved in with his parents. After his alcoholism became too much for them, they soon kicked him out, too, and Buck found alternative living arrangements with a coworker on temporary basis. But that eventually fell through, too.

With the little money Buck had saved up from his construction job, he blew it all on a hotel room and more booze until he found himself with no money and nowhere to go. While he never resorted to sleeping on the streets, Buck killed time in public spaces like Depot and Lawrence parks, where he was sometimes yelled at by people driving by who accused him of being a crackhead and told him to get a job.

This June, Buck sobered up and sought assistance from social workers at the Samaritan House, Kalispell’s only homeless facility that provides a shelter program, as well as both transitional and permanent housing for clients.

Buck started attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and he got a job at Subway. He’s been connected to services with CAPNMT and he’s working to find permanent housing.

Although Buck has been sheltered while he’s been homeless, he says Bryan’s death has made it hard to trust people.

Samaritan House Executive Director Chris Krager said he now asks his clients if they feel safe when they arrive at the shelter, and he said many of them don’t.

With limited shelter services in the valley, Krager is planning a roughly $15 million expansion at the Samaritan House known as the Building Stability project, which will entail a remodel of the old Army Reserve Armory in Kalispell. With plans to break ground next year, the project will offer 40 pop-up shelter beds and 18 two- and three-bedroom apartments that will qualify for HUD Section 8 housing vouchers. The plan also brings 15 single-occupancy units for homeless veterans – a gap in the Flathead Valley.

“This will solve a lot of the community’s problems,” Krager said.

In addition to the Samaritan House’s expansion, community leaders are working to solve broader issues related to homelessness.

Horn, with the Warming Center, has spearheaded a homeless council that will involve stakeholders ranging from unsheltered people to business owners to elected officials. Her goal is to come up with community solutions and bridge the gap between stakeholders.

“There’s hostility between groups and when we can better understand each other, there’s less hostility,” Horn said.

Kalispell Mayor Mark Johnson said he has met with Horn to begin the selection process and he says while it’s new territory, he’s hoping to open some lines of communication.

“I have a lot of constituents saying we need to do something,” Johnson said. “People ask, ‘Where are they coming from?’ and ‘Why can’t you just load them on a bus and ship them somewhere else?’ There’s a breakdown and disparity between the expectations some of the people have with public behaviors.”

Chief Venezio believes the community is facing a problem that will require a full spectrum of collaborative partners to fix.

“Any conversation we are having regarding this issue needs to include all stakeholders,” he said. “Everybody needs to come together and realize this problem is very large and it takes a lot of different ideas and funding sources from government, nonprofit and private industry.”

At Bryan’s Memorial, Nate Small, who was homeless last winter, said officials need to take accountability for the negative rhetoric that’s been established toward the homeless population.

Reflecting on his homelessness last winter, Small said he met a wide range of individuals he described as having hit rock bottom, but who were willing to fight to get out of poverty. Still, he remembers getting harassed as he struggled to get through each day.

“I was cold and hungry with the world looking down at me,” Small said. “Some people loved me, some people helped me, but most of them hated me.”