Montana Caving Expert Awarded for Decades of Service

Glacier National Park officials recognized Hans Bodenhamer, aka “Mr. B,” for more than two decades of cave exploration and conservation

By Micah Drew

When Hans Bodenhamer first began exploring caves in America’s national parks 40 years ago, he did so in the dead of night, far from the prying eyes of National Park Service rangers.

It was the 1980s and Bodenhamer, in his early 20s, didn’t have a lot of faith in how the Park Service was managing their subterranean assets. He figured he might as well try to learn as much as possible to protect the underground resources, with or without the government’s blessing.

“I ended up just sneaking around in the Grand Canyon going to all of these caves illegally,” Bodenhamer said. “Caves are all pretty remote; all the rangers did was patrol the rims and popular trails.”

At one point, Bodenhamer believes he’d accessed more caves in the Grand Canyon than anyone else, and in a tight-knit community like the caving world, it didn’t take long before officials figured that out.

Eventually, Bodenhamer was caught and arrested, not for illegal caving, but for an illicit rafting trip down the Colorado River without a permit. The arresting ranger was Butch Farabee, a prominent National Park Service ranger known for his alpine rescue work in Yosemite National Park during the 1970s “Stonemaster” era of rock climbing.

“We were flown out by helicopter, and I was talking to the ranger, pointing out every cave we passed by on the flight out,” Bodenhamer recalls. Farabee was fascinated by Bodenhamer’s encyclopedic knowledge and thought he could be useful to the agency.

“I was arrested, flown out and then they set up a grant for me and I ended up doing cave management work,” Bodenhamer said.

Nearly four decades after his arrest, Glacier National Park administrators have recognized Bodenhamer for more than two decades of service exploring, mapping and conserving caves in Glacier and other remote areas of the West, as well as for passing along his passion for conserving caves to a new generation of enthusiasts.

“He’s truly been invaluable to the park. He’s a guy with a lot of experience as a cave specialist; he’s been out there, he’s not just an academic thinking about caves,” said Richard Menicke, Glacier’s geographer and GIS manager, who presented Bodenhamer with the award in late November. “When you take that, and couple it with someone who’s changing lives, how could you not want to shout that out?”

Caves are akin to the moon, Bodenhamer explained. The infamous inaugural footprint of Neil Armstrong, for example, is still emblazoned on the lunar surface. With no wind or rain, it’ll stay there as it was for thousands of years, like a fossil preserved in amber.

“Caves are like that. For the most part, there’s not much going on through these caves in terms of rain or wind or disturbances,” Bodenhamer said. “The floors are incredibly fragile, mineral features hanging from the ceiling or rising from the ground grow at incredibly slow rates, over millions of years.”

The fragility of these sites prompts a duty to conserve them in pristine conditions, one that Bodenhamer has curated over decades spent underground.

Bodenhamer can’t recall exactly when he developed his passion for caving, but he can remember crawling around Devil’s Den, a boulder-strewn hillside near the Gettysburg Battlefield in Pennsylvania, in grade school. In his teens, he started exploring local caves with his father, his first caving buddy who “wasn’t too into it.”

“It was an interesting evolution from there. In the early years I was into the gymnastics of moving through the caves. You’d crawl and climb and do some rope work,” Bodenhamer said. “Then I wanted to go to as many as I could, then I got into going to caves no one had been to before and I wanted to be the first. Then I got into mapping and most recently it’s been the conservation side of things and getting my students involved.”

By the time Bodenhamer and his family moved to Montana in 2004 he’d already fallen in love with the local caving scene from several visits to the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area, where he’d discovered caves even more wild and remote than those in the Southwest.

On one of the first days of his teaching career at Browning High School, Bodenhamer attended a ceremony honoring the change of a derogatory peak name in nearby Glacier National Park. One of the park officials at the ceremony was none other than Farabee, the ranger who had arrested Bodenhamer during his illicit Grand Canyon trip and was serving as the assistant superintendent at Glacier. Farabee knew there were caves in the park that needed to be surveyed, and he enlisted Bodenhamer, by then a well-known cave cartographer, to explore and inventory Glacier’s stock of subterranean caverns.

“When I first encountered Hans to my best recollection, we knew we had three caves in the park, and we knew they were sensitive,” Menicke said. “But that was about it. Hans discovered and mapped at least a dozen more that we had no clue existed when he started out.”

With the backing of Menicke and wildlife biologist Lisa Bate, Bodenhamer surveyed the park’s existing caves, which included mapping them, inventorying geologic formations and traces of animals, and establishing protocols to monitor the resources.

By utilizing GIS concepts and mapping tools, Bodenhamer was able to extrapolate what bands of rock the known caves were in and modeled a park-wide geologic map to begin searching for new ones, often “by dragging his students out there,” Menicke said.

Initially, he enlisted students from the Browning High School Outdoor Leadership and Exploration Club, but later formed the Bigfork High School Cave Club; combined, Bodenhamer estimates he’s taken around 400 students into the depths of the earth. They’ve learned to create maps, distinguish between bat guano and wood rat droppings and collect data for research projects in units throughout the National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service.

“They get really jazzed out in the field,” Bodenhamer said, adding that he sees students undergo the same evolution of enthusiasm for caves in four years that took him 40. “They can’t get these experiences out of a textbook. You don’t see this motivation and enthusiasm out of anything else.”

“I have a plethora of facts about caves, and those facts do nothing for me in my current work as a wildland firefighter, but it still gives me a lot of passion,” said Colten Wroble, a 2022 graduate from Bigfork High School and a member of the Bigfork Cave Club. “Cave Club gave me something to be excited about. I’m 100% convinced that I wouldn’t have graduated high school if it weren’t for my Cave Club trips with Mr. B.”

The Bigfork Cave Club offers students the rare opportunity to venture deep into the wilderness, explore barely visited rifts in the ground, and collect data that contributes to meaningful scientific research. The trips often include facing extreme environmental and natural adversities — army crawls through narrow muddy passageways are standard fare, for example, as are frigid underwater creek crossings, 6-foot-long clusters of spiders, and even bear encounters — but students emerge having cultivated unique memories, a deep-seated love of nature and a desire to contribute to the conservation story of a place.

“Sometimes caving really sucks. Like it really sucks,” Wroble said, recalling one of his first trips that involved having to change into rappelling gear in the middle of a snowstorm. “Sometimes you’re sitting at the bottom of a dark pit waiting for people to climb up a rope, which isn’t super fun, but Mr. B. has a really good way of keeping things lighthearted, cracking jokes, and offering chocolate. Every trip is a great memory.”

Wroble, along with fellow Cave Club member Ryan Cantrell, was recognized in 2020 by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) with the President’s Environmental Youth Award (PEYA) for their work developing a web-based system using citizen science to collect information on bat populations in Montana caves, a project that helped land managers better understand future impacts of White-Nose Syndrome, a deadly fungal disease found in North American bats.

That award was just one of numerous accolades bestowed upon student members of the Bigfork Cave Club under Bodenhamer’s tutelage. The club and two individual members previously won the PEYA in 2009 as well as the 2019 Wildlife Conservation Award from the Montana Wildlife Society. Club members have also been selected as speakers at international GIS conferences, keynoted conventions of the National Speleological Society, and met U.S. presidents.

Time and time again, “Mr. B” turns students into speleological experts and lifelong stewards of these undergroundresources.

“He’s such a unique individual. The amount of energy he puts into Cave Club and his students isn’t passion, it’s obsession,” Wroble said. “He’s obsessed with caving and instills that into every single kid who goes through his club.”

Wroble, who currently lives in Flagstaff, Ariz., still goes caving on most weekends along with another former Cave Club alum, Tabitha Raymond, as well as other cavers Mr. B introduced them to while in high school.

“Caving is just such a unique thing you get to do,” Raymond said. “For me, cave club was my way to decompress from life stress. Mr. B was such a fun person to be around and has so much passion for what he’s doing that he tries to pass along.”

Raymond said her experiences with Mr. B made her “super into rocks” and led her to declare a geology major at Northern Arizona University, with plans to work in cave conservation.

“There’s such a unique and precious ecosystem that only occurs in caves, and it’s a necessary thing to study and preserve them,” she said. “It’s not something many people think about in their day-to-day lives, but I already had an affinity for it.”

Gabriella Eaton, a 2017 graduate from Bigfork, is another Cave Club alum working in an adjacent field. Eaton is doing graduate work at Glacier Park involving White-Nose Syndrome in bats, working for a boss she first met on a Cave Club trip, and was elated when she heard Bodenhamer was going to be recognized.

“Mr. B changed my life big time. I don’t think I’d be doing what I’m doing gnow if it weren’t for him,” Eaton said. “He just deserves a lot of credit.”

Her own memories from caving trips remain stamped in her memory – scrubbing graffiti from cavern walls, snowshoeing for miles to survey caves in winter, learning to glissade down a snow field on the way back, wading through more than 1,000 feet of chest-high, near-freezing water to access a new section of cave that needed to be mapped, and more.

“Looking back, a lot of those experiences were so comical. Those adventures just set the tone for the rest of my life to this point,” she said. “It’s cool to go places and be able to say, ‘oh, I’m one of the only people who’s been here before. There aren’t many places on Earth anymore that you can say that about. It’s unique and special, especially for teenagers.”

Cavers confront a lot of the classic phobias — spiders, darkness, heights, water, cold — but Bodenhamer fosters an environment to help them overcome those fears, or at least understand them better, Eaton said.

“He could always push students to get outside their comfort zones, but never pushed anyone too far,” she said. “He just always knew how to talk people through what they were dealing with, whether it was rappelling through a dark cliff, or being tired and cold on a hike out from a trip. He’s still a huge mentor, and the coolest person I know.”

Bodenhamer has discovered, surveyed, and mapped more than 100 caves across Montana, including some of the most remarkable subterranean features on the continent.

In 2005, Bodenhamer was a member of a caving party that discovered Virgil the Turtle’s Great House Cave, beneath Turtlehead Mountain in the Bob Marshall Wilderness. The cave was mapped to a depth of more than 1,500 feet, the second-deepest limestone cave in the United States at the time.

Subsequent expeditions in the area with various caving partners have led to the discovery of additional caverns and crevices in the area, including Tears of the Turtle, which requires more than 44 rope drops to reach the bottom and, at 2,052 feet deep, is currently the deepest limestone cave in the country.

“Scientifically speaking, it’s unknowable how much he’s contributed to the state’s knowledge,” Dan Seifert, a former National Forest Service geologist and Cave and Karst Program lead who has worked with Bodenhamer and the Bigfork Cave Club to share resources and cave knowledge in Montana.

Seifert said that one of the biggest contributions Bodenhamer has made to the state’s karst knowledge has come through digitizing cave survey maps, allowing land management agencies to better monitor the resources.

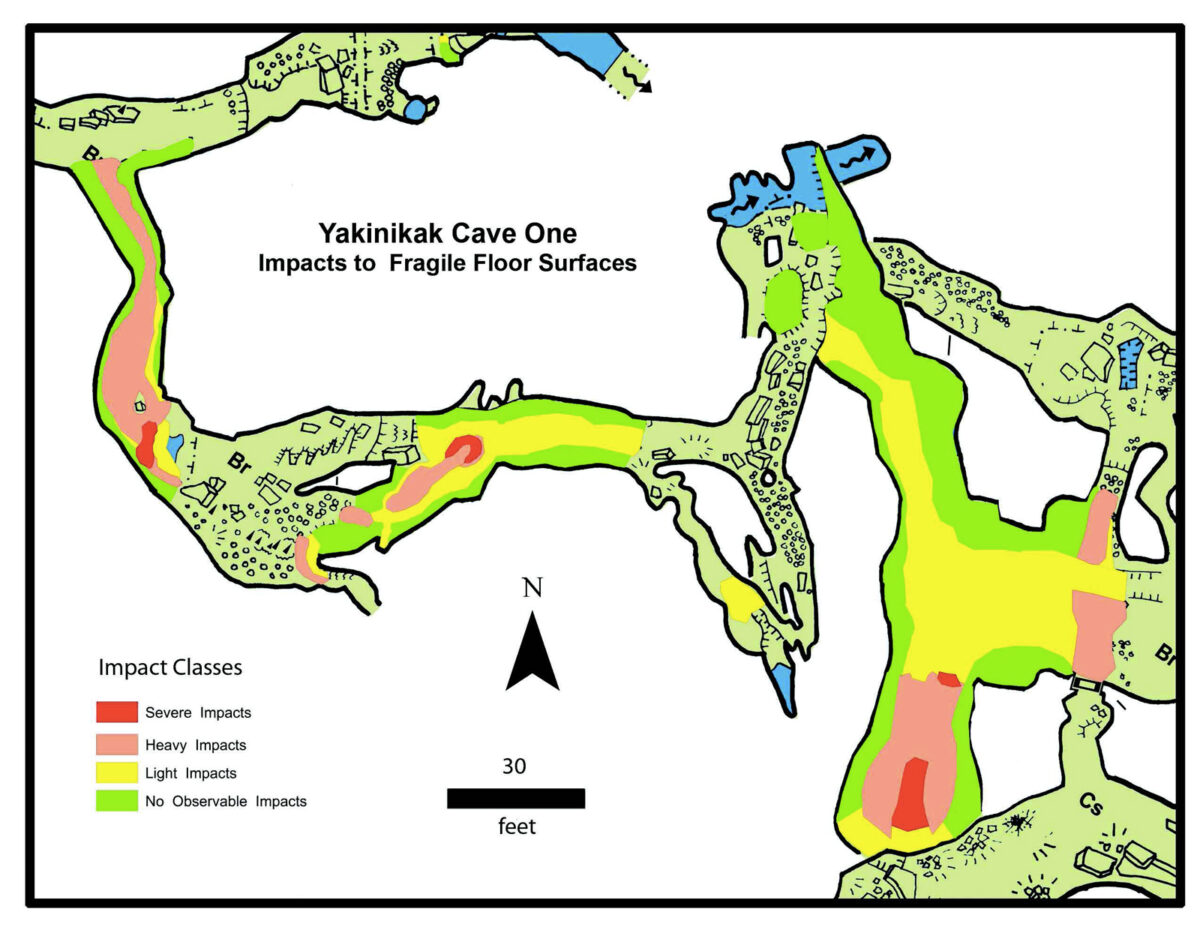

Coining the term “visitor impact mapping,” Bodenhamer developed mapping protocols with his students that involve periodic site visits, repeat photographic monitoring and detailed mapping — sometimes down to individual footprints on the cave floor. Changes in visitor traffic, concentration of bat guano and hydrology can be monitored overtime, and his methods have been adopted by resource managers around the country.

“It’s vital work that wouldn’t get done if it weren’t for Hans and his students,” Seifert said.

In 2018, Bodenhamer and some of his students spoke at a national caving conference in San Diego, Calif.,about how their use of GIS maps and local conservation work has paved the way for conservation projects around the state — even on the surface. In the GIS-specific class Bodenhamer teaches at Bigfork High School, students often work on projects in collaboration with the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service.

Between his teaching career and Cave Club, Bodenhamer has developed an entire philosophy around using experiential learning to inspire the next generation to care about the world at large.

“Caves are symbolic of the way we treat the whole world. We have resources on the surface that maybe heal a little faster, but if we learn to take care of caves, we might find a method for taking care of other parts of nature,” Bodenhamer said. “The kids get this right away, and I think it stays with them.”