Ruis to Purchase CFAC Property for Residential, Commercial Development

Terms of the 2,400-acre land sale require EPA to finalize remediation plan for the shuttered aluminum plant’s contaminated property that follows waste-in-place recommendation

By Tristan Scott

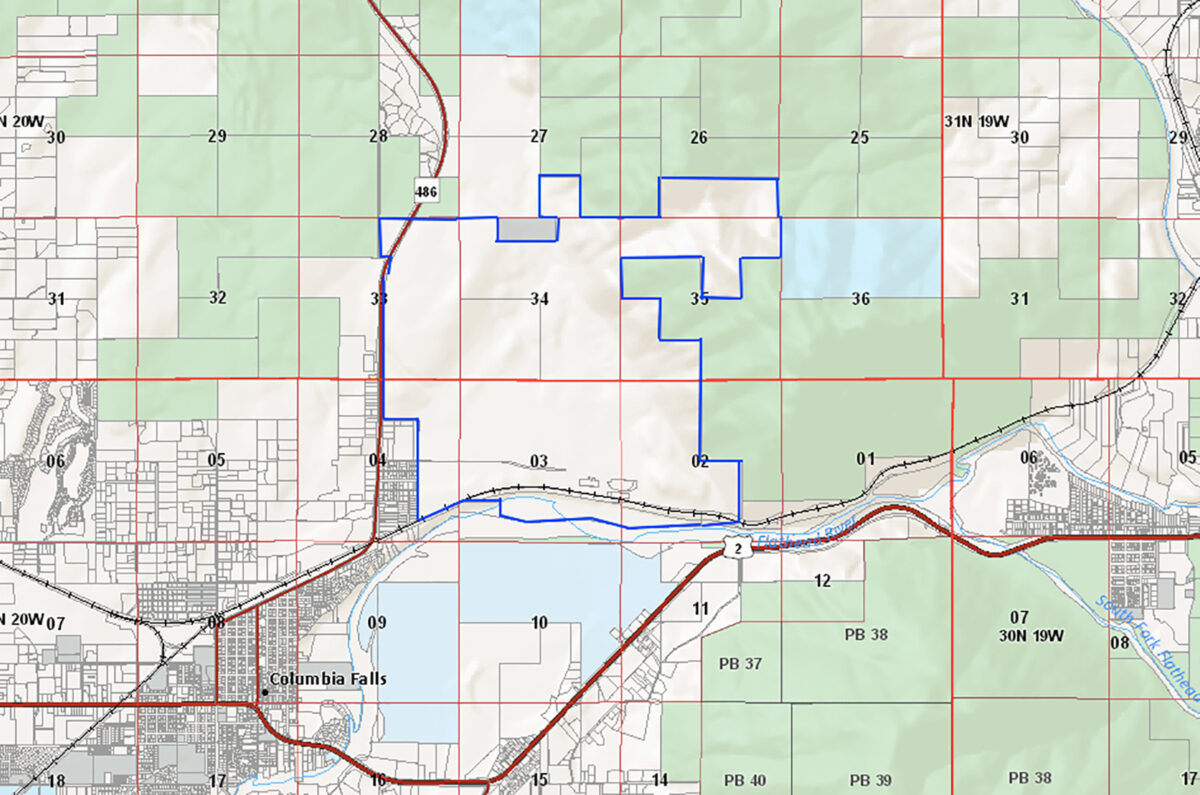

A high-profile developer with a track record of revitalizing overlooked corners of the Flathead Valley is slated to purchase 2,400 acres of land from Columbia Falls Aluminum Company (CFAC), whose shuttered aluminum plant property along the Flathead River is undergoing the final phase of environmental assessment under the federal Superfund program.

While the terms of the sale are contingent on state and federal regulators finalizing the details of a $57.5 million proposed cleanup plan that would contain rather than remove the contaminated waste, the prospective buyer, Ruis Construction owner Mick Ruis, a prominent developer in Columbia Falls, indicated in a prepared statement Wednesday that he would use the property to build affordable housing, as well as open the area to commercial and industrial growth.

“This area has the potential the city needs for affordable housing and growth,” Ruis stated in a press release distributed by CFAC, which is owned by the Swiss commodities firm Glencore, Ltd. “Real estate prices in the Flathead Valley have skyrocketed in the past few years, putting the American dream of home ownership out of reach for many Montanans. We want to build houses at a better rate so more people can afford to live here.”

The transaction is expected to close once the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) releases its formal Record of Decision, according to the press release, with the remediation plan “as currently recommended” by the EPA and the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

Ruis was not immediately available for an interview on Wednesday.

Located northeast of Columbia Falls on the Flathead River, the CFAC site was once home to an aluminum reduction facility. Approximately 40 chemicals have been identified as contaminants of potential concern at the site, including cyanide, fluoride, arsenic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

From its famous opening in 1955 through the boom years of the 1960s and ’70s, the facility fueled this rural corner of Montana with over 1,500 jobs — almost half the population of Columbia Falls in those days — and millions of dollars in new economic investment. The plant closed in 2009, putting hundreds of employees out of work. The EPA declared it a Superfund site in 2016, ensuring that the property’s owner, Glencore, as well as former owner the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) are held financially accountable for cleaning up any hazardous materials and addressing other environmental impacts. At the conclusion of a trial in 2021, a federal judge in Missoula apportioned liability between Glencore and ARCO, determining that ARCO is responsible for 35% of past and future cleanup costs with the remaining 65% is allocated to Glencore.

Throughout the regulatory process, company officials say they’ve fielded scores of inquiries from interested parties looking to redevelop and repurpose the site, but that Ruis’ interest marks the first time a deal has been set to close.

“After an extensive investigation and consultation process spanning almost 10 years, we are excited to see what this area will become and for the Columbia Falls community to live, work and play here,” Glencore’s Cheryl Driscoll said in the prepared statement.

CFAC Project Manager John Stroiazzo said the land sale does not include the roughly 200 acres of property the remedial investigation identified as the source of contamination, including the landfills and a buffer zone.

“We are retaining ownership of that until the remediation work is completed and the EPA has signed off on it,” Stroiazzo said, emphasizing that the company has spent $14 million to date funding the remedial investigation and feasibility study.

“It’s not like we are going to sell and run,” he said in an interview. “We have paid all our bills on time and there has never been a dispute over ownership or cost. We’ve reached a point in the process where we understand the site, and in my view, generally, and I think most folks would agree that this is a good time to take the next step toward getting into remediation and redevelopment.”

Contained within the 2,400-acre property that is part of the sale is a 1,340-acre area the EPA identified as the Superfund study area, as well as about 507 acres on which industrial activities occurred, including the aluminum plant site and warehouses, as well as attendant infrastructure.

“The site is a prime candidate for commercial development,” Stroiazzo said. “There’s the rail line, natural gas line, a nice level plot of land that doesn’t need a lot of preparation, several large buildings that can be repurposed, parking lots, it’s already zoned for commercial and industrial, and it’s neat and out of the way. The infrastructure is there so the next step in development is going to be relatively cheap.”

Still, as news of the potential sale reverberated through the Flathead Valley on Wednesday, not everyone cheered the development as a positive step, particularly in light of recent steps by Montana Justice Department’s Natural Resource Damage Program to assess and recover damages from the corporate entities responsible for the toxic contamination. Under the Superfund laws, a pre-assessment screen is the first step in the process to determine whether the trustees can make a successful claim and should proceed with a natural resource damage assessment (NRDA) for the site.

For Erin Sexton, a research scientist with the Flathead Lake Biological Station who in 2016 served on the CFAC Community Liaison Panel and advocated for a Superfund designation, the pre-assessment screen suggests to her “that those entities don’t think the site is going to be sufficiently cleaned up.”

“That is an important signal that stakeholders are not confident that [Glencore] is going to own the price tag in the event of future damages,” Sexton said. “So who assumes the liability?”

“I would hate to see the promise of redevelopment, of a situation that is very, very good news, somehow negatively affect our assurances that the property is cleaned up to the degree it needs to be,” she added.

Those concerns are underscored by the formation earlier this year of the Coalition for a Clean CFAC, which is urging residents to join a petition requesting the EPA and DEQ “take a timeout to fairly evaluate the cost-benefits of removing (not leaving) the toxic waste at CFAC,” according to the group. Specifically, it asks the regulatory agencies to delay a Record of Decision based on the proposed waste-in-place plan outlined in the 2021 Feasibility Study and the 2023 proposed cleanup plan for the Columbia Falls smelter site, which was developed in cooperation with CFAC.

“The petition calls out that no cost analysis of removing this highly toxic waste was done by CFAC’s consultants when drafting the cleanup plan,” according to an email from the organization. “Rather, it was dismissed as too costly.”

Indeed, the remedial investigation and feasibility study does highlight the logistical difficulties of waste removal, including noting that the nearest hazardous waste disposal facility is 500 miles away, while “off-site disposal would negatively impact neighborhoods and the environment for years while increasing the potential for traffic accidents, injuries and inadvertent contaminant releases during transport.”

The Coalition for a Clean CFAC isn’t alone in urging the EPA to pause its assessment and Record of Decision. Earlier this year, the Flathead County Commission also urged the EPA “to postpone its final determination on the cleanup” of CFAC “until a comprehensive evaluation is conducted,” according to a Feb. 12 letter that all three commissioners signed and sent to EPA.

“This evaluation must thoroughly assess the potential impacts on the pristine waters of the Flathead River, Lakes, and the Columbia River headwaters that could result from the retention of a million cubic yards of hazardous waste on-site,” the commissioners wrote. “Additionally, it should entail a thorough cost analysis comparing the removal of waste versus capping and lining in place, with a focus on the implications for the next century and beyond.”

In Sexton’s experience, “waste-in-place isn’t usually the most protective option over the long-term,” particularly when it involves moving water, as with the Flathead River. And while she understands the frustration of local stakeholders who want to see their community cleaned up and repurposed, she said the Superfund designation furnishes the cleanup project with valuable tools.

While Sexton said her professional involvement in the CFAC saga dovetails with her personal involvement, as she and her family live near Columbia Falls.

“Unfortunately, there isn’t a hurry-up option when it comes to Superfund and it isn’t because the federal government is slow,” Sexton said. “It’s because they are legacy contamination sites. The pollution took a long time and these sites take a long time to clean up and restore.”

Dana Barnicoat, community involvement coordinator with the EPA’s Region 8, wrote in an email that the agency is aware that “the sale of a portion of the property raises questions and concerns among the community about the future of [the CFAC site].” Barnicoat said the sale of the property will not affect the ongoing Superfund process or the review of public comments on the proposed plan for site cleanup “as the agency works toward a final Record of Decision.”

“The EPA wants to reassure the public that we will continue to oversee and enforce cleanup of the site and ensure protectiveness of human health and the environment. If the sale becomes final, the EPA, in collaboration with the Montana Department of Environmental Quality, will work with both CFAC and the new owner to ensure the site meets all legal requirements concerning protectiveness and reuse.”