Cold, Dark and Lonesome

In 1960, a Montana-raised airline pilot on reserve duty crashed a Navy fighter jet in the darkest depths of Flathead Lake in a case that remains cloaked in mystery. Investigators initially said the crash was the result of unauthorized pilot error, and while new evidence has restored the Marine’s honor, neither his body nor the plane were ever recovered.

By Butch Larcombe

The Grumman F9F-8 was a fast, highly maneuverable fighter jet used in pilot training and by the Navy’s Blue Angels to entertain thousands in the late 1950s. But how one of the jets, flown by a Montana-raised airline pilot on reserve duty, came to rest in the darkest depths of Flathead Lake in 1960 is an enduring mystery.

John Floyd Eaheart was raised in Missoula, played shortstop as a youth and graduated from Missoula County High School. Attending what was then known as Montana State University (later renamed the University of Montana), he played baseball and basketball and received a degree in physical education. After graduation, he flew combat missions over Korea and remained in the military until 1957. He signed on as a pilot for Western Airlines in 1958 and served in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve. (The Marine Corps is part of the U.S. Navy.)

As part of his reserve duty, Eaheart completed training flights, a number of them with Montana as a destination. On March 21, 1960, he left Los Alamitos Naval Air Station in southern California, refueled the fighter at Hill Air Force Base in Utah and continued north to Malmstrom Air Force Base in Great Falls. After a short stay at Malmstrom, Eaheart filed a plan for a flight of about 1.5 hours and headed west towards Missoula, making at least one pass over the city where his parents and a sister lived, at an altitude of less than 1,000 feet, according to officials.

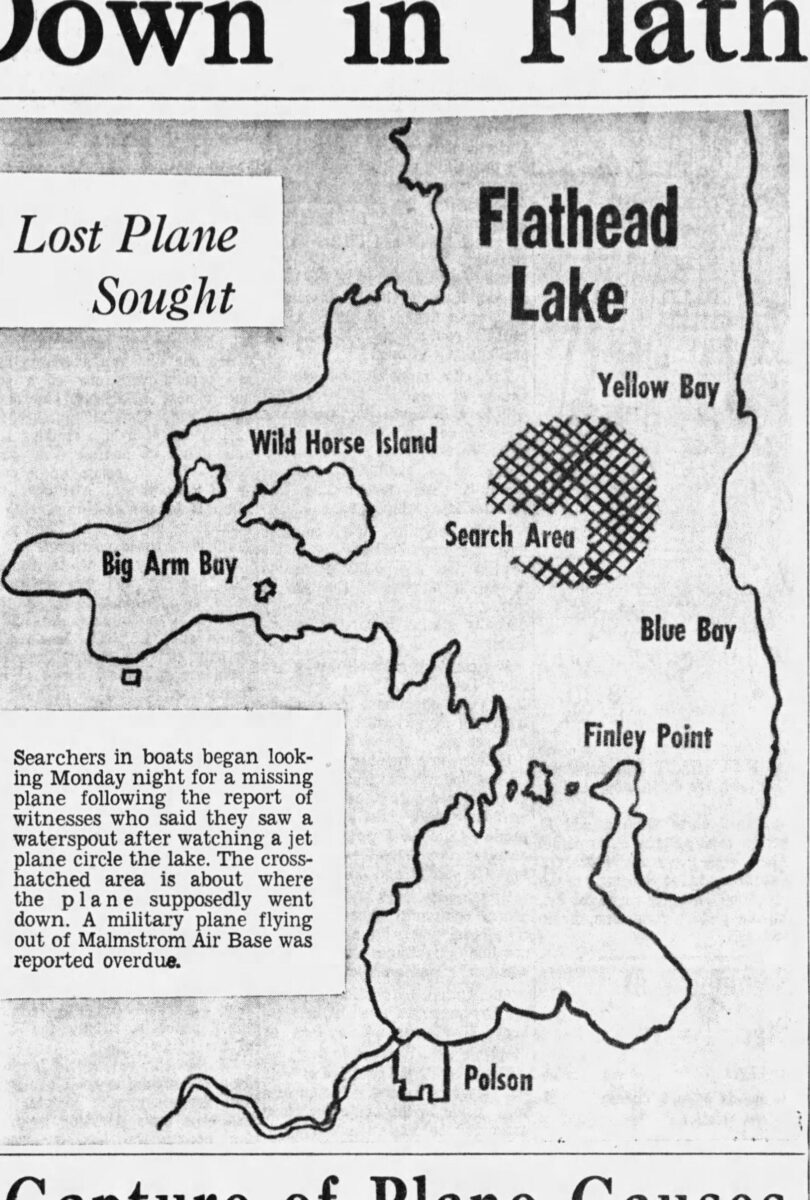

From Missoula, he flew north towards Flathead Lake, headed for the east lakeshore home of the parents of Vi Pinkerman, his girlfriend who, at the time, was in Denver, where she worked as a flight attendant. Eaheart, according to a Navy report, made several passes over the Blue Bay and Yellow Bay area as darkness gathered that evening, the passes witnessed by several people, including K.C. Pinkerman, his girlfriend’s father, who was outside his home. He offered this account of the final pass to the Missoulian newspaper: “The plane came in from the south at an altitude of 600 to 700 feet and circled the Blue Bay and Yellow Bay area and then headed on a northwesterly course. At about 2,000 feet, it went into a left turn and about a 30-degree glide downwards from which it never came out.”

Another witness, Mac Niccum, the owner of the Holiday Resort at Yellow Bay, reported seeing the jet buzzing the lake as he stood on the deck of his home. “It was going down and up and all around,” Niccum told a reporter. “The last time we saw it, it headed off to the west pretty high. The next thing we saw was a water spout about 200 feet high.”

Several witnesses, including Niccum, reported hearing an explosion after spotting the water spout. One witness reported hearing several explosions. Those reports were the source of considerable speculation in the days, months and years following the crash of the Navy jet. It is unclear whether any of the witnesses saw the plane go into the lake.

Officials determined the plane entered the water at about 7:25 p.m., approximately 45 minutes after sunset, at a spot roughly between Blue Bay and a point on Wild Horse Island. While reports of the likely crash sparked calls to law enforcement, searchers weren’t able to reach the suspected crash site for several hours, and efforts to find Eaheart or the plane were hampered by darkness.

A key player in the search was the S.S. Hodge, a 65-ton stern-wheeler work barge piloted by Frank Hodge, one of several generations of a family that traversed the lake in all variety of watercraft, including steamboats, over many decades. Hodge recalled the search effort to an interviewer in 1965: “They got me out at 9 that night and we covered the area all night with search lights. At 2 the next afternoon, we found some debris, about an acre of it, floating in the middle of the lake. We used a marked trolling line to find the depth. It was deep, 255 feet. All we could do was put out a marker buoy.”

Among the items found were a flight jacket, a pair of Navy dress trousers, a green battle jacket, a checkbook and a helmet that contained brain matter. Also found were wooden ribs from the plane’s fuselage.

“A (Navy) salvage officer flew up from Frisco and looked the scene over,” Hodge recalled, adding that the officer said, “I’m going to recommend to the admiral that we leave it [the jet] just where it is.”

Hodge added: “And that’s just what we did.”

Despite not having recovered the jet or the pilot’s body, a Navy investigative team from Whidbey Island Naval Air Station in Washington finished a report into the crash in early April 1960, about three weeks after the crash. The report, which didn’t find its way into the public realm until decades later, said there was no indication that structural or mechanical issues played a role in the crash. The plane, in service for 39 months with 973 hours of flight time, had undergone a thorough inspection just six days before Eaheart’s flight to Montana and had adequate fuel to continue flying. There was no distress call from the plane or evidence that the pilot tried to eject, which would have been proper procedure in a case of engine failure, according to the report.

The Navy report stated that the Eaheart’s flights over Missoula and Flathead Lake were not part of the flight plan he filed at Malmstrom and stated that “it must be assumed” that the pilot was aware that the low flights “were unauthorized and extremely dangerous.” The report also noted that Eaheart had made a number of similar passes over the Pinkerman home on earlier training flights.

Noting the clear skies and calm conditions, the report speculated that Eaheart may have suffered from a loss of depth perception due to the glassy condition of the lake’s surface and could have been looking toward the Pinkerman home instead of ahead at the immediate flight path when the plane hit the water. The location of the damage on Eaheart’s helmet, supported that theory, according to investigators. Other factors aside, the report said, “It is the opinion of the Board [of Investigation] that the primary cause of this accident was unauthorized low flight.”

Noting the recovery during the search of several ribs and pieces of fuel cells from the jet’s fuselage, the Navy speculated that impact of the jet hitting the water while flying at more than 350 knots may have caused the engine to smash through the fuselage and two fuel cells, causing the plane to break apart, possibly triggering the explosion reported by witnesses.

After the initial recovery of the helmet, clothing and fuselage components within about 24 hours of the crash, further searching in the following days yielded no more sign of the plane or Eaheart. On March 29, 1960, a Navy officer told Floyd Eaheart that there was no possibility his 32-year-old son had survived the crash and the search had officially ended.

For nearly a half-century, the story of the plane and the pilot lingered largely in the memories of family members, searchers, witnesses and a few others. A simple rectangular headstone memorializing Eaheart’s birth and death was placed in the Missoula City Cemetery. Eaheart, who had been named to the Grizzly Hall of Fame in 1955, was later honored for his basketball prowess with an annual award given to the UM basketball’s top defensive player. Vi Pinkerman married Escoe Lewis and the couple moved to Flathead’s east shore, where they lived for decades.

But the story of the missing plane and pilot found new life in the spring of 2006, when a Kalispell man named John Gisselbrecht orchestrated a private search, which involved the efforts of Sandy and Gene Ralston of Boise, Idaho, who donated the use of side-scan sonar equipment and a submarine-like remotely operated vehicle with a video camera. On May 2, the couple and others spotted an aileron, a portion of a plane’s wing, on the lake bottom at a depth of about 275 feet. A couple of days later, the searchers, joined by a cadaver dog – a black Labrador named Ruby who reportedly pawed at the water at the suspected crash site – located a Marine Corps boot, other remains and possibly a deployed parachute.

Gisselbrecht, who told reporters and others that he had been doing research into the crash for 15 years, said he believed the crash was not the result of pilot error. Relying heavily on witness accounts of the crash, he offered a theory that the F9F-8 experienced issues that caused the engine to malfunction on its final pass over the lake. The pilot may have put the plane into a dive in an attempt to restart its engine. Gisselbrecht theorized that when that effort failed Eaheart may have tried to eject from the plane moments before it went into the lake. He speculated that the plane’s canopy may have failed to open properly and the pilot may have been critically injured when he collided with the canopy.

“He was not hot-dogging or showing off,” Gisselbrecht said at a press conference in Missoula in 2006. “He was in an airplane prone to compressor stalls. This is a Marine who stayed at his post until the last possible second. It doesn’t get any more honorable.” He said his search effort, which didn’t involve the Navy or local authorities, was focused on “restoring the honor of a Marine.”

The 1960 crash likely occurred before aircraft were commonly fitted with flight data recorders, a device that could offer information on the final flight of the fighter jet and possible engine problems. Even if the Navy plane did have a flight recorder, known informally as “the black box,” finding it on the silty lake bottom roughly 275 feet below the surface would be challenging.

Efforts to determine if the U.S Navy had done further investigation into the crash after the discoveries of 2006 were unsuccessful. A Freedom of Information Act request submitted to the Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington, D.C. in 2022 by this author was denied; while officials said the agency had documents and information related to the incident, those materials were exempt from disclosure because they were “predecisional” and contained privileged information. “There’s no further information available regarding this incident,” officials wrote.

In an interview in 2019 as part of a Bigfork oral history project, Vi Lewis recalled the jet crash, relying largely on recollections of what she was told by her parents and others. She also offered another possible explanation for the crash: the jet piloted by Eaheart suffered mechanical problems after hitting a flock of geese. That possibility was the result of a conversation between her father and Frank Hodge, whose big boat was the first to reach the suspected crash site.

“Hodge and Dad kind of thought that maybe he ran into a bunch of geese because there were a lot of goose feathers out on the lake,” Lewis told interviewer Scout Jessop, a Bigfork High School student. Lewis said witnesses noted that there were large flocks of geese migrating through the Flathead Lake area around the time of the March crash. “The geese were heading north and he was heading south.” Planes striking birds are regarded as a significant threat to aviation safety, according to experts. Birds hitting a plane’s engine can cause significant damage or even cause it to cease operating.

Lewis, who died late in 2022, watched the 2006 search activity from the shore. She also went out on a boat on the lake as part of the search effort, telling a news reporter that she had mixed feelings about the possibility that Eaheart’s body might be found. “I had learned to live with the fact that he was there and I didn’t want him disturbed,” she said.

Contacted after the discovery of the remains, Eaheart’s relatives said that they would like his body removed if possible, allowing him to be buried next to his father in Missoula. After watching the video from the bottom of the lake, Lewis changed her mind and concurred, concluding the lake was simply too “cold, dark and lonesome” to be a final resting place.

Contacted in 2023, a member of the pilot’s extended family said there was no indication that the Navy had retrieved any part of the plane or Eaheart’s remains. “I don’t think they want to go get him,” the relative said. “It’s too deep and too cold.” And in the view of the Navy, “it’s ancient history.”

A version of this article will appear in Butch Larcombe’s upcoming book, “Historic Tales of Flathead Lake,” which will be published by The History Press and is due out in June.