Escaped Hatchery Trout Pose Hybridization Risk to Native Species in Flathead River Basin

An investigation by Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks detected inadvertent releases of nonnative rainbow trout from the Creston National Fish Hatchery, which could further imperil native westslope cutthroat trout

By Tristan Scott

For nearly two decades, a growing body of evidence has revealed that crossbreeding between certain fish species is detrimental to the persistence of native trout in the Flathead River system, providing natural resource managers with a clear-sighted conservation strategy: preserve the drainage-specific genetic adaptations hardwired into these wild trout over the course of millennia and they’ll be better equipped to survive wildfires, floods and drought in the future.

To understand the perils of hybridization, one need not look any further than Montana’s state fish, the westslope cutthroat trout. Once the most widely distributed cutthroat trout subspecies in North America, westslope cutts — so named for the side of the Continental Divide they occupy — now inhabit just 10% of their historic range.

The primary threat to westslope cutthroat trout? Invasive rainbow trout.

But even as hybridization swamps the genetic qualities that give cutthroat their superpowers, the Flathead River Basin remains a range-wide stronghold for the imperiled fish, giving rise to a new era of fisheries management that has led to landscape-scale conservation efforts across northwest Montana, including in remote corners of the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area and Glacier National Park.

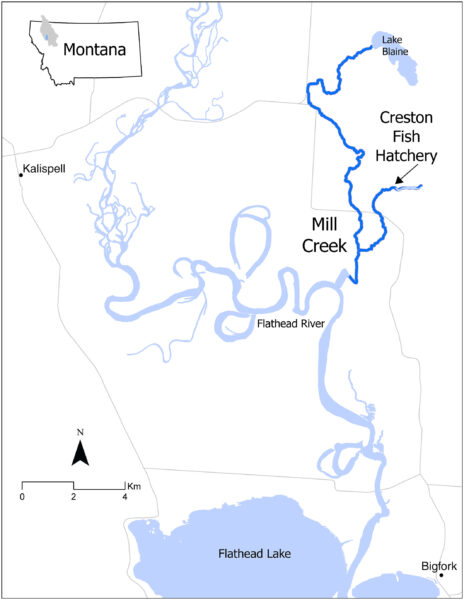

So it was with a heavy heart that a state fisheries biologist recently reported his discovery that the Creston National Fish Hatchery had been inadvertently introducing invasive rainbow trout into Mill Creek, a tributary of the Flathead River.

“We found that 83 of the 106 rainbow trout we collected (78%) were of hatchery origin,” explained Sam Bourret, a Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks biologist who published his findings last August in the American Fisheries Society’s peer-reviewed scientific journal, “Fisheries Magazine.”

Using forensic geochemistry extracted from the inner ear bones, or otoliths, of captured fish, Bourret has gained a reputation for using the innovative sleuthing technique to investigate illegal fish introductions. In 2018, for example, he used the pioneering research tool to trace the origin of nonnative walleye discovered in Swan Lake to an illegal introduction in 2015. Otoliths are a calcium carbonate structure that contain unique geochemical identifying tracers, which, in the case of the Swan Lake walleye, revealed that the illegally introduced fish matched the geochemical signature of walleye from Lake Helena in central Montana.

At the time, Bourret said he hoped the forensic tool would help curb future illegal fish introductions by notifying the public that FWP was serious about cracking down on so-called “bucket biologists.” But he didn’t expect to turn the technology on a federal fish hatchery.

Like a tree’s concentric growth rings, the otolith reveals a history of a fish’s growth as well as a record of its migration pathways — a kind of geochemical diary of its life. Using that microchemistry data, Bourret was able to analyze the isotopic values and discern which rainbow trout captured in Mill Creek had been reared feeding in a natural environment, and which had been consuming the marine-derived food sources used to raise trout at the Creston hatchery.

“We knew the different food sources would have different geochemical thumb prints, so it set us up with the perfect scenario,” Bourret said. “I didn’t set out on this project thinking that we’d trace these rainbow trout to the hatchery. We need hatcheries and this was clearly an unintended consequence. But since I was able to quantify it and draw this connection, it kind of opened the door to communication and forced them to take a look at what changes they could make to prevent the problem from occurring again in the future.”

Those changes were set in motion when Bourret revealed his discovery to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) program manager at the Creston National Fish Hatchery, who began trying to identify the source of the leak “and to remediate these to reduce inadvertent entry of hatchery [rainbow trout] into the stream,” according to Bourret’s study, “Inadvertent Hatchery Rainbow Trout Discovered in Native Westslope Cutthroat Trout Habitat: A Cautionary Tale,” which was co-authored by Jill M. Janak; Tim J. Linley; Megan K. Nims; and Geoffrey A. McMichael.

“The [rainbow trout] rearing structures at the hatchery are over 60 years old and tests confirm water leakage through the concrete may be serving as a conduit for small [rainbow trout] to enter Mill Creek,” the study states.

According to Laura Jenkins, assistant regional director for FWS’s Mountain-Prairie Region communications office, the purpose of the Creston National Fish Hatchery is to support stocking requests from a variety of partners, including FWP and other federal, state and tribal hatcheries.

“Unintended fish escapement is a potential risk at all fish hatcheries and, as data became available related to escapement at Creston [National Fish Hatchery] … hatchery staff began working closely with partners requesting fish,” Jenkins wrote in an email to the Beacon. “They have worked collaboratively to convert part of their annual rainbow trout production to triploid (sterile) rainbow trout, which reduced the risk of hybridization.”

Creston National Fish Hatchery staff are also in ongoing discussions with the Blackfeet Nation to convert some additional rainbow trout production to other species of fish, Jenkins said, including kokanee salmon — a species previously produced at the Creston hatchery, and one that does not hybridize with native cutthroat trout.

“Additionally, they continue to assess their infrastructure to identify possible avenues of escapement and are in the process of procuring and installing additional sealing materials to mitigate potential areas of concern in their rearing areas,” Jenkins wrote. “Finally, they have initiated planning and design phases to evaluate and develop increased isolation capabilities at Creston [National Fish Hatchery].”

For Bourret, the study “serves as a cautionary tale for the potential of hatchery facilities to inadvertently compromise conservation efforts when nonnative species are reared outside of their aboriginal ranges.”

Those conservation efforts include a landscape-scale conservation project that unfurled across the South Fork Flathead River drainage between 2007 and 2017. Representing the largest conservation effort in the country aimed at restoring native westslope cutthroat trout, the project sought to replenish the South Fork drainage upstream of Hungry Horse Dam with genetically pure populations of westslope cutthroat trout. Recognizing the pressure of hybridization on native fish, the architects of the South Fork Flathead Cutthroat Conservation Project systematically removed nonnative fish from 21 lakes in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area and the Jewel Basin and replaced them with pure westslope cutthroat trout. The project required the use of a piscicide called rotenone to poison the invasive fish populations before re-stocking could occur.

Although controversial at its inception, fisheries managers say the effort has been biologically successful, and has served as a conservation model with applications elsewhere, including last summer in Glacier National Park’s Gunsight Lake. It’s also gained broader support from the public as the benefits have been proven over time.

But Bourret said it’s challenging to convince members of the public that an intensive conservation strategy like what occurred on the South Fork is necessary when the same invasive species it’s targeting are sneaking out of a federal facility in a connected drainage.

“Here we are going deep into the Bob Marshall Wilderness and dumping rotenone into Sunburst Lake to neutralize a hybrid population of westslope cutthroat trout that are 5% rainbow trout, and there’s 100% rainbow trout entering the same watershed from the hatchery,” Bourret said. “It just didn’t sit right.”

Despite the benefits that hatcheries provide, Bourret’s study concluded that they also pose apparent risks to native fish populations.

“Reducing inadvertent entry by hatchery fish not only lowers the risks to native species, but also reduces resources, energy, and money needed to produce fish for their intended use,” the study said. “Careful examination of the risks associated with these facilities, particularly in the watersheds where they are located, is critical to responsible stewardship of native species.”

As populations of westslope cutthroat trout wink out elsewhere, Bourret emphasized the rarefied space that the Flathead River system and its connected waterways occupy among ecosystems.

“These cutthroat are migratory. They grow big in Flathead Lake and then return to the tributaries where they spawn,” Bourret said. “It’s an evolutionary advantage to know where you’re born because you know you can go home to reproduce. In most other places outside the Flathead, the habitat is so fragmented that those migratory life histories can’t exist. What we have here is exceedingly rare.”