At 50, Blackfeet Community College Looks to the Future

Last month, Blackfeet Community College celebrated 50 years as a tribal college. Grounded in its history as a cultural institution, the college is expanding its academic programs to meet changing community needs.

By Denali Sagner

Editor’s Note: This story is part of The Rural College Project, an ongoing series about efforts to expand access to higher education for Indigenous and rural students in Montana. This series was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.

Brad Hall calls Blackfeet Community College (BCC) the “intellectual and cultural heart of the Blackfeet Nation.”

Set against the backdrop of Glacier National Park to the west and rolling grassland to the east, the college is a central figure in Browning and the Blackfeet Reservation. Hall, its president, has led the college since 2022. Before taking the helm of BCC, Hall held a number of administrative positions and was, most recently, the first tribal outreach specialist at the University of Montana.

Over five decades, BCC has shaped the Blackfeet community, and the community has shaped the college. It is a center of higher education for the Blackfeet Nation, training students in nursing, scientific research, teaching, Piikani language and a growing list of subjects. It’s also a repository for Blackfeet tradition and language — a place where Blackfeet history is recorded, preserved and woven into the fabric of student life.

While BCC’s mission to educate students and support tribal life has stayed true over 50 years, Hall and college leaders have maintained an eye on the future, which is being shaped by economic needs and a growing desire for workforce programs. In recent years, the college has honed in on career education, from industry trades to nursing, helping students build sustainable careers in their home communities.

BCC opened its doors in 1974 as an extension of Flathead Valley Community College (FVCC) after tribal leaders saw a need for higher education on the reservation and, as Hall described, “breathed purpose into the college.” BCC’s first five graduates were all women. Hall said the college’s early development was part of the broader tribal college movement, during which tribes sought greater control over the education of their children and the preservation of their languages and traditions.

In 1980, BCC struck out on its own, becoming an independent institution. By 1983, enrollment reached 315 students. In 1985, the school was accredited by the Northwest Association of Schools and Colleges, now known as the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities. In 1994, the federal government designated BCC and six other tribal colleges in Montana “land-grant institutions,” allowing them to apply for federal trust funds through the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Prior to becoming land-grant universities, per-student funding at Montana’s tribal colleges lagged far behind that of non-tribal institutions. In 1993, tribal colleges received $2,974 per full-time student compared to an average of $6,997 for non-tribal community colleges, the Great Falls Tribune reported at the time. The lack of funding had strapped tribal colleges, making it difficult to keep up with their non-tribal peers.

“Being a land-grant college is really important for tribal colleges,” Hall said. “A lot of our experiences that students have is on the land.”

BCC’s status as a land-grant institution reshaped the scope of the college, allowing it to expand its STEM programs and bring in millions in federal grants.

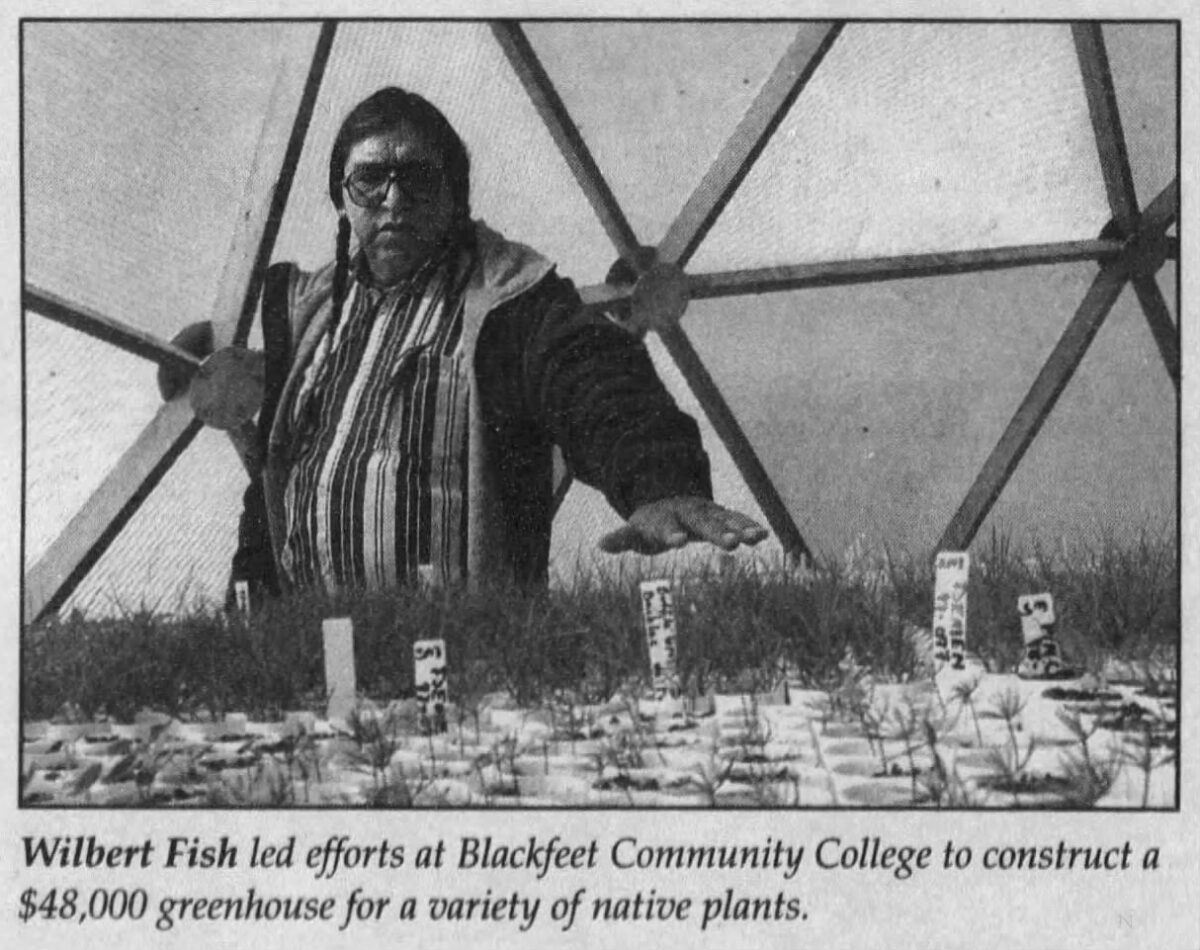

In 1999, ethnobotanist and Montana State University extension agent Wilbert Fish led a successful effort to construct a state-of-the-art greenhouse for the study and cultivation of native plants. The greenhouse was owned by the college and funded by grants from the National Park Service, the Bureau of Reclamation and Montana State University. A few years later, the college received two grants from USDA — $185,000 to undergo handicap-accessible renovations and $3.1 million to build an administrative services facility, conduct research and renovate student learning spaces. Federal grants have funded programs from beaver dam construction to a new mobile meat processing facility.

Now, it’s one of seven tribal colleges in Montana. As a two-year college, BCC offers a variety of associates and certificate programs and often serves as launching pad for students to earn a four-year degree at partnering colleges and universities.

This year, BCC introduced new certificates in industry trades and human subjects research, as well as a degree program in anthropology. Following the pandemic, Hall said, demand for online learning has exploded, especially on the rural reservation, where students can live far from school and childcare demands can interfere with in-person attendance.

The tribe now has a fully functioning Institutional Review Board to review scientific research, which has been ongoing at the college since 2012.

Under Betty Henderson, the chair of BCC’s Math and Science Division, Blackfeet students and researchers published peer-reviewed studies on stress and cortisol levels in Native participants. They also developed community-centric interventions that improved participants’ health outcomes.

“Because Native Americans suffer health disparities, we die a lot younger, we have a lot more health issues,” Henderson said of her team’s research. “Who better to study this or figure out some answers than ourselves?”

Through the “2+2 program,” Blackfeet students can earn a four-year teaching degree through the University of Montana Western while completing their education in Browning. Around a dozen students are trained each year to become nurses through the college’s four-year licensed practical nursing program. Last year, 22 students became certified nursing assistants through an intensive two-week course hosted by BCC and the Montana Department of Labor and Industry.

“We almost try to be everything for everybody, because the needs are so great,” Hall said, a tall challenge for an institution facing the post-pandemic budget and enrollment pressures that are impacting colleges across the country.

BCC’s enrollment dropped during the pandemic, and educators said, nearly five years later, they’re finally seeing students come back to the classroom in earnest.

“It’s been a really good year,” Hall said.

Part of the college’s success has been its innovation in workforce programs, which allow students to learn tangible skills without the time and monetary commitment of a traditional, four-year degree.

Cheryl Madman, workforce development director for the college, said that as the tribe’s baby boomers retire, there aren’t enough young people to replace them in the workforce.

Teaching practical skills, from solar panel installation to commercial driving, is helping to ease that shortage.

“These younger kids just want to get a certification,” Madman said, reflecting changing attitudes towards college.

According to a 2023 study by the Pew Research Center, only one-in-four U.S. adults said it’s extremely or very important to have a four-year degree in order to get a well-paying job in today’s economy.

Over the past two years, Madman’s department certified 39 commercial drivers and offered microcredentials to workers looking to advance their skills. This July, BCC hosted a solar installation training program, where 10 students learned solar construction skills and earned a $1,000 stipend while doing so.

“A lot of careers anymore don’t necessarily require a four-year degree,” BCC Vice President Jim Rains said.

While Rains, a longtime educator and tribal college administrator, said he believes fundamentally in the value of a liberal arts degree, he understands students’ changing needs and the college’s responsibility to fill gaps in the local workforce.

“There’s been kind of a shift in higher ed,” Rains said. “Where colleges are trying to be more responsive to both students and their needs, as well as employers and what they’re looking for in graduates.”

The heart of BCC, however, extends beyond its degree and workforce training programs. The college, Rains and others explained, is the tribe’s cultural core, a place where language, history and culture is preserved for generations to come.

Each student, from industry trades to nursing, is required to take courses in Blackfeet culture and Piikani language.

Years of assimilation and oppression forced Blackfeet language and customs into the shadows, leaving only a few thousand Piikani language speakers across the U.S. and Canada.

“When we think back, even 20 years ago, 30 years ago, we were taught a lot of shame,” BCC Director of Institutional Development Melissa Weatherwax said. “It was taken away from us, and it’s up to us to pick it back up.”

“When we’re able to reconnect through our culture, it’s a return to self,” she added.

The college is looking to launch a four-year degree in Piikani studies, as well as in wellness and leadership. Through these programs, Weatherwax said, students will be able to learn a Piikani-first approach to nonprofit administration and leadership, helping the college cultivate the next generation of tribal leaders.

“The college has become one of those places where those things get preserved,” Rains said, speaking about Blackfeet tradition. “If it’s not done formally, if it doesn’t reside within an institution, it’s hard to preserve that.”

Without offering a place for the community to document, preserve and learn its history and language, Rains added, “We’d just be a two-year college.”

Last month, BCC celebrated 50 years as a college. College leaders honored BCC’s first graduating class with gifts to graduates’ families. Speakers recounted the college’s early days, celebrated the growth of the institution, and looked to the future.

Speaking to college officials, guests and community members, Hall praised “the continuous growth of the college” and the “new and emerging partnerships” helping usher it into the future.

In the years ahead, Hall and his colleagues hope to expand the college’s four-year degree capacity, increasing opportunities for students to earn high-level degrees without having to travel hours from home.

“I think the Blackfeet College has a tremendous opportunity to be a really unique college as it develops into a four-year institution,” Rains, the BCC vice president, said.

Challenges remain. Student recruitment and retention pose ongoing concerns. Though the college hopes to attract more enrollees and professors from outside of Browning, there’s currently no dedicated living space for students or staff. Each new program will require funding, staff and interested participants. Especially during the winter, reliable transportation is difficult to find.

Yet with its growing campus and “living classroom” of surrounding Blackfeet land, college leaders see a bright future ahead.

“Primarily, we feel like we’re on the right track when it comes to what the community needs,” Hall said, discussing the college’s new strategic plan.

As programs expand, Hall and others say they are committed to the college’s core mission, to be a place of community, of education and of cultural preservation.

“We want them to be grounded in who they are. We want them to be able to celebrate what they are in their studies,” Hall said of BCC’s students. “We hope that all directions lead back to the community.”