As Montana Adopts New Fishing Regulations, Wild Trout Rise Up as Conservation Priority

With angling and environmental pressures ramping up on streams and rivers, the state Fish and Wildlife Commission voted to reel in recreational angling for bull trout in the Flathead, extend a ban on treble hooks and lower the bag limit for wild trout across western Montana

By Tristan Scott

As fisheries managers attempt to rescue the region’s native trout populations from an existential crash, the Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission on Tuesday further restricted opportunities for recreational anglers targeting bull trout in the Bob Marshall Wilderness and Hungry Horse Reservoir while extending a ban on multi-pointed hooks to include the entire Flathead River system.

But perhaps the more notable development benefiting the state’s wild trout populations was the conservation lodestar the commissioners turned toward in adopting more stringent limits not only for threatened bull trout, but all wild trout caught on the rivers and streams in Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks’ western and central districts.

Adopted as an amendment to Montana’s 2025-2026 fishing regulations, the new rule on combined trout limits (not including westslope cutthroat trout) lowers the daily possession maximum for trout caught on Montana’s rivers and streams in the western and central districts from five to three, a step that Pat Tabor, vice chair of the commission, said follows a widespread catch-and-release philosophy that most anglers have already adopted in response to warming water temperatures, depleted stream flows and increased angling pressure.

“There’s an ethic that exists in this state that matches, in essence, what we’ve got here. It really does,” Tabor, a Whitefish resident, said of the amendment during the commission’s Nov. 12 meeting in Helena, where they approved the new regulations. “My support of this … is because I want to protect these fisheries for multiple decades and I feel like memorializing that we are purposely being conservative in our wild stock management, that is a philosophy that I want us to wholly embrace, both as a commission and as a department, because things are changing. Our habitat is changing. Our water temperatures are changing. We’ve constantly got the threat of disease and everything else. So, we have to do everything we can to fight to protect the efficacy of the [wild trout] populations here and I don’t want to react after it’s too late. I want to proactively put something in place that protects the fish from here to come.”

The proactive-versus-reactive realignment comes as climate change has depressed stream flows, caused water temperatures to spike and disrupted migratory patterns for trout across the state. In the past year, that confluence of factors led fisheries managers to implement a raft of management actions, including enforcing unprecedented river and stream closures to mitigate the damage to wild trout, as allowed by the state’s adaptive fish management plan.

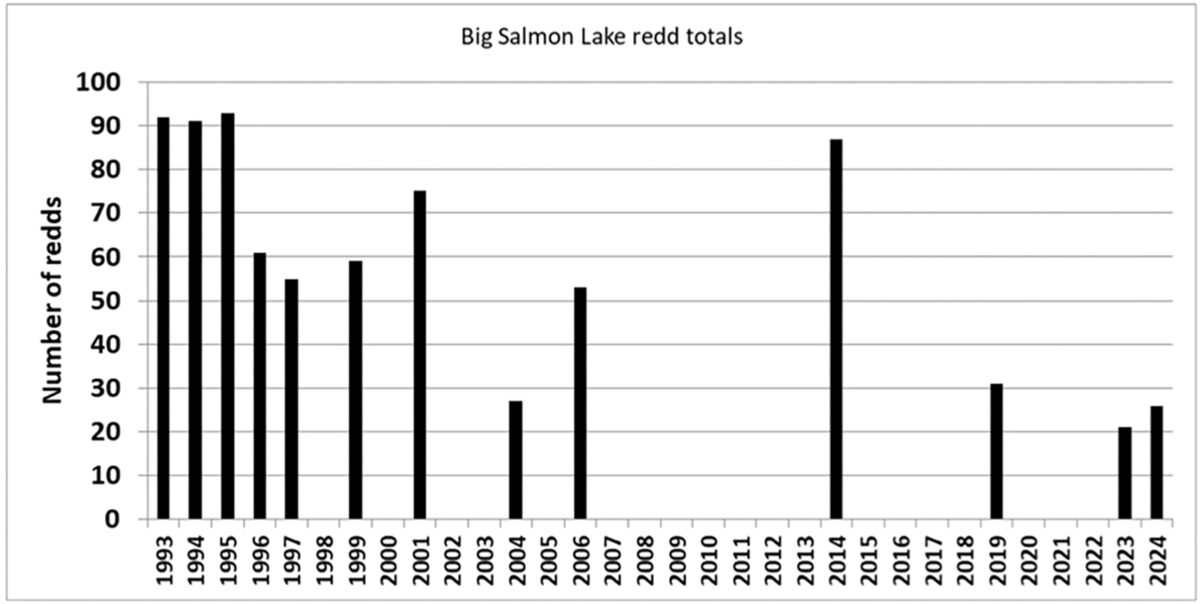

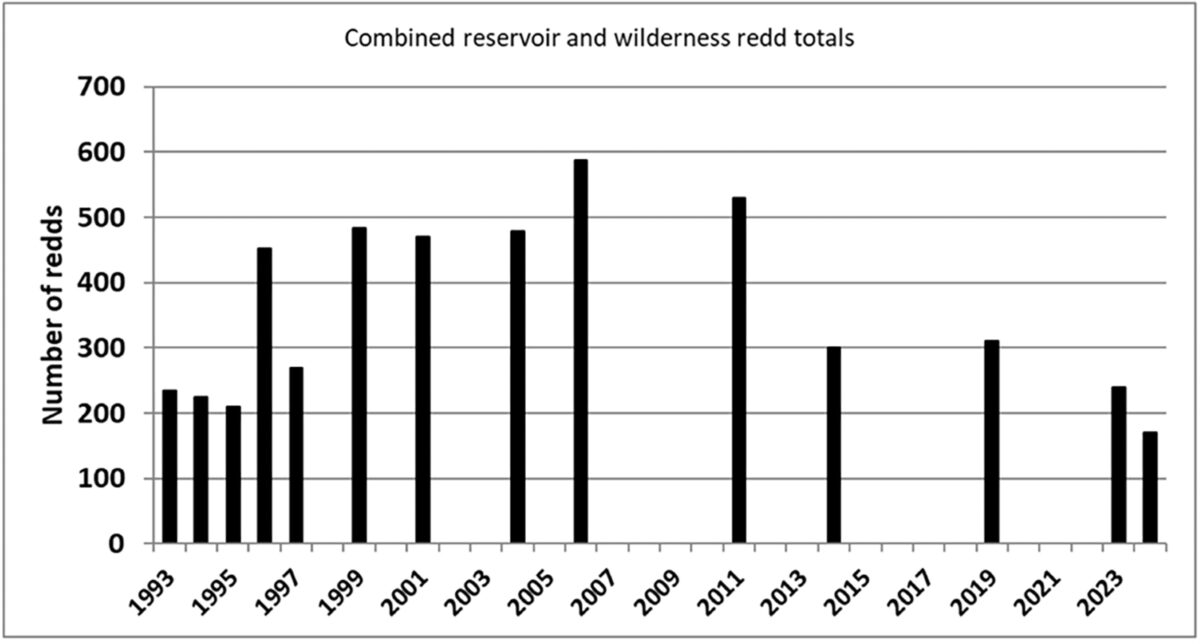

In July, for example, local fisheries managers for the first time imposed angling restrictions on the North Fork Flathead River along the western border of Glacier National Park, where water temperatures broke daily records for a period of weeks, stressing the region’s native trout populations. This fall, when fisheries crews tallied the lowest bull trout population counts in the South Fork Flathead River since 1993 — the second consecutive year that they tracked dramatic declines in the number of spawning nests in what has historically been a stronghold for the native trout species — fisheries managers tasked with bull trout recovery were so alarmed that they immediately drafted a host of proposed changes to the upcoming year’s fishing regulations, just in time for the Nov. 12 Fish and Wildlife Commission meeting.

But the broader philosophy of wild fish management took shape in Montana a half-century ago, in 1974, when FWP stopped releasing hatchery-raised fish in the state’s rivers and streams. In the early 1980s, after monitoring the effects of the new philosophy in different locations and on different species, FWP established a five-fish harvest standard that has endured for decades. The agency has reduced the standard to three trout on 28 rivers and streams in the western district as conditions have demanded.

Although fishing pressure has increased dramatically across the state since that time, most Montana’s anglers have become more focused on the quality of the fishing experience, “rather than bagging fish for the frying pan,” according to Commissioner K.C. Walsh, the former owner of Simms Fishing Products. While evidence suggests that most of Montana’s anglers practice catch-and-release fishing for wild trout, Montana is experiencing significant population growth “and newcomers are likely to bring different angling values,” Walsh said in justifying the new limit, adding that an abundance of opportunities still exist for anglers to harvest fish in the state’s lakes and reservoirs.

“My overriding thought in this is that the mission of Fish, Wildlife and Parks is to steward the fish, wildlife and parks as a recreational resource for the public now and into the future,” Walsh said. “I perceive my role as a commissioner to think about strategically what this state is going to look like in five or 10 years and how we can get ahead of some of the issues we are struggling with.”

Using standard creel and fish population survey tools to monitor populations, FWP has determined that an overwhelming majority of anglers throughout Montana are already practicing catch-and-release ethics. For example, recent data from a longstanding creel survey on the Missouri River below Hauser Dam showed that, of the 16,000 rainbow trout caught by surveyed anglers from 2019 to 2023, catch-and-release rates averaged 87%. Additionally, preliminary data from FWP’s 2023 Angler Pressure Survey identified that 97% of anglers surveyed while fishing the Madison River practiced catch-and-release fishing.

“Similar catch-and-release rates by anglers have been observed or documented for streams and rivers across Montana where the current district standard applies,” according to Walsh.

Some commissioners raised concerns that FWP’s preoccupation with the established five-fish limit, which for years has been amended on a site-specific basis as fisheries on certain rivers and streams required it, came across as less biological in nature and more social; however, Tabor countered that the two factors are inextricably linked.

“To me, this really is biological in nature from the standpoint of looking forward to the preservation of our wild stock population,” Tabor said. “Can we anticipate an increase in population and angling pressure in the next 20 years? Yes we can. Can we anticipate pressure from environmental concerns such as water quality or temperatures? Yes we can. All those conditions are in place and what we have been doing, rightfully so, is adapting when the data becomes critical and indicative enough that we need to do it. And when you look at statistics of how many people are keeping the fish, most of them are keeping a very modest amount. They’re not keeping up to the entire bag limit; they’re usually keeping a couple. And so, in some ways we’re actually matching the behaviors on the ground. But it’s also in anticipating that in the last 10 years we have been adding rivers pretty consistently because of concerns of water temperatures and angling pressure. Isn’t it predictable that we are going to see that trend continue and so maybe we get ahead of it?”

Tabor, who recently retired from the Swan Group of Companies, which operates a full spectrum of outfitting and recreation services in northwest Montana, has emerged as a champion of wild trout conservation in recent years, including by supporting a gillnetting program that targets invasive lake trout in Swan Lake, where native bull trout nests have also declined. Similarly, Walsh, who owned Simms for nearly three decades, relocating the company in 1993 to Bozeman, is promoting an alliance between the economics of angling in Montana and its ecological health.

In some cases in the past, sportsmen and outfitter groups have pushed back on strategies to suppress populations of introduced fish for recreational purposes, but those interests have increasingly been swayed by environmental factors as the consequences become more evident.

To that end, the new fishing regulations enjoyed support from trade groups such as the Montana Outfitters and Guides Association (MOGA) and the Fishing Outfitters Association of Montana (FOAM), as well as conservation groups like Montana Trout Unlimited.

Will Israel, executive director of MOGA, endorsed the proposed regulations and their amendments, saying they “align with modern angling ethics and encourage a shift to quality over quantity, supporting conservation as anglers increasingly prioritize fish health.”

“Lower limits help manage fish populations sustainably under growing fishing pressure,” Israel said. “Similar regulations in neighboring states have been shown to support healthy trout populations and thriving recreational fishing economies. While regulations guide, education and community involvement are crucial for shifting angler behavior or sustainable practices.”

The Montana Wildlife Federation (MWF) opposed lowering the bag limit because it “infringes upon the opportunity for harvest-oriented anglers and subsistence anglers”; however, MWF supported limiting opportunities for recreational bull trout in the Flathead River Basin.

On Tuesday, Tabor carried all four amendments related to bull trout on FWP’s behalf, including limiting intentional angling for bull trout on the South Fork to a month-long period from July 1 to July 31. The former season began on the third Saturday in May and ran through July 31.

The regulation changes come as FWP is seeing record low numbers of bull trout spawning nests, known as redds, in many areas in the South Fork Flathead River watershed, including in Big Salmon Creek and other tributaries.

“I appreciate Vice Chairman Pat Tabor’s work on these important amendments regarding the bull trout fishery,” Jay Pravecek, FWP’s acting fisheries division administrator, said in a prepared statement. “Our department believes and the science tells us that reducing fishing pressure and handling of bull trout will help stabilize the declining population numbers in these waters.”

Bull trout were listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act in 1998. Historically one of the strongholds for bull trout in Montana, the South Fork is the only river in the state that allows the intentional fishing for bull trout through a limited season.

“These changes are intended to be a proactive measure that maintains limited fishing opportunity but reduces the amount of handling stress on bull trout,” Leo Rosenthal, an FWP fisheries biologist based in Kalispell, said. “These fish are important ecologically and culturally, but they are also an important sport fish. We want to maintain opportunity for anglers to pursue this unique native species.”

Angler surveys show that 44% of bull trout caught in the South Fork of the Flathead River are caught in the lowest portion of the river. Migrating bull trout in the lower portion of the drainage are vulnerable and, by shortening the season, Rosenthal said fish will be able to migrate to their natal streams without being targeted by anglers. Additionally, bull trout are known to congregate near the mouths of key spawning tributaries like Little Salmon Creek and Gordon Creek. These confluence areas have well-defined holes and are known areas to target concentrations of staging bull trout. Reducing the amount of angler-induced handling stress may help stabilize the downward trend in adult bull trout numbers.

For Rosenthal, as well as other fish ecologists and anglers in the region, the proposed changes to fishing regulations aren’t meant to be permanent; rather, they’re an opportunity to determine how much of an impact angling pressure is exacting on the local bull trout populations.

Clayton Elliott, the conservation and government affairs director for Montana Trout Unlimited, said the newly adopted regulations regarding bull trout in northwest Montana sets “a perfect example of using data to manage regulations.”

Here are the changes to bull trout regulations:

- Big Salmon Creek: Closed to all angling within a 300-yard radius around the inlet (where the creek enters the lake) of Big Salmon Lake.

- Big Salmon Lake: Closed to all angling within a 300-yard radius around the inlet (where the creek enters the lake) of Big Salmon Lake.

- Hungry Horse Reservoir: One fish per license year from the third Saturday in May through Aug. 15. Catch-and-release the rest of the year with a Hungry Horse/South Fork Flathead permit validation on fishing license. A Hungry Horse/South Fork Flathead Bull Trout Catch Card must be in possession when fishing for bull trout. See bull trout under “What do I Need to Fish in Montana” of the 2025 Montana Fishing Regulations. All bull trout must be released immediately or killed and counted as your limit when harvest is allowed. It is unlawful to possess a live bull trout for any reason.

- South Fork Flathead River: No intentional angling for bull trout except catch-and-release from July 1 through July 31. Angling is prohibited from the mouths of Gordon Creek and Little Salmon Creek downstream 300 yards from June 15 to Sept. 30. A Hungry Horse/South Fork Flathead Bull Trout Catch Card must be in possession when fishing for bull trout. See bull trout under “What do I Need to Fish in Montana” in 2025 Montana Fishing Regulations for application information. All bull trout must be released promptly, with little or no delay. It is unlawful to possess a live bull trout for any reason. Angling for bull trout is not allowed in South Fork Flathead River tributaries or Big Salmon Lake.