Hockaday Museum of Art in Kalispell Announces Name Change

The museum, which inhabits a historic Carnegie Library Building, originally took the Hockaday name in honor of the Lakeside artist Hugh Hockaday

By Mike Kordenbrock

Following a vote at a September board meeting, the Hockaday Museum of Art has officially changed its name to the Glacier Art Museum.

In the intervening months since board members granted approval, word of the name change trickled out before executive director Alyssa Cordova shared the news more broadly at a late-November fundraiser at Somers Mansion. On Wednesday, the museum director announced the name change in a press release.

The museum, which inhabits a historic Carnegie Library Building in Kalispell, originally took the Hockaday name in honor of the Lakeside artist Hugh Hockaday, who moved from St. Louis to Lakeside in 1946, but whose family history with the Flathead stretches back to the early 20th century.

According to Cordova, the name change is one element of a strategic plan to gain accreditation from the American Alliance of Museums. After two years of work, the plan was finalized in May.

“One of the things that kept resurfacing was a need to update the name of our museum to better reflect our commitment to the art and artists that we serve and the area and the community that we’re in, and our close ties and proximity to Glacier National Park,” Cordova said.

While the name is changing, Cordova said that Hugh Hockaday will remain central to the museum’s story, and that it retains some of his work in its collection.

The museum’s board voted 4-2 in favor of the name change, with one additional board member voting present.

“I think we’ll have different views of this name change, but people can be assured that we didn’t take this lightly,” Cordova said. “And that there was a lot of time and thought that was put into this change, and we feel it’s the best decision for the future of this museum.”

Other changes are coming for the museum, including unveiling a new logo and launching a new website in the spring, while changes to the museum’s signage and branding will progress over the next 12 to 18 months.

Mike Roswell, the board chair for the Glacier Art Museum, said in a press release that it became clear during the strategic planning process that the museum needed a name “with a broader reach and recognition for both local and out-of-state visitors.”

Roswell continued: “We believe that we have a new opportunity to tap into the increasing population of the Flathead Valley with a moniker that conjures immediate images of the Park.” The board chair said he also anticipates the name change and strategic plan allowing the museum to strengthen its connection with Glacier National Park and to grow its programming, collection, staffing and facilities.

The Glacier Art Museum was originally conceived of as an arts center. Hugh Hockaday, who was deeply involved with the local art community, died in 1968 before it opened, which prompted efforts by the Flathead Valley Art Association to name it in his honor.

Cordova, the museum’s current director, said the museum’s name has changed through the years, from the Hockaday Memorial Center for the Arts to the Hockaday Center for the Arts and, most recently, the Hockaday Art Museum. Cordova said that in researching the history of the museum’s name she found records showing that names similar to the Glacier Art Museum had been registered by the museum in 2005 with the State of Montana’s Department of Commerce, even as the museum’s name remained unchanged.

Hockaday’s granddaughter, Kimberly Hockaday Quinby, said in an interview with the Beacon that she was saddened to hear about the change, but that she sympathized with the difficulties that art institutions face.

“It’s a bummer because you want your family to be remembered, and having my grandfather’s legacy remembered was a lovely thing. But I understand,” she said, adding that “being in the art world is a hard thing. Money is always a hard thing. The more closely they can associate themselves with the park, it’s probably better.”

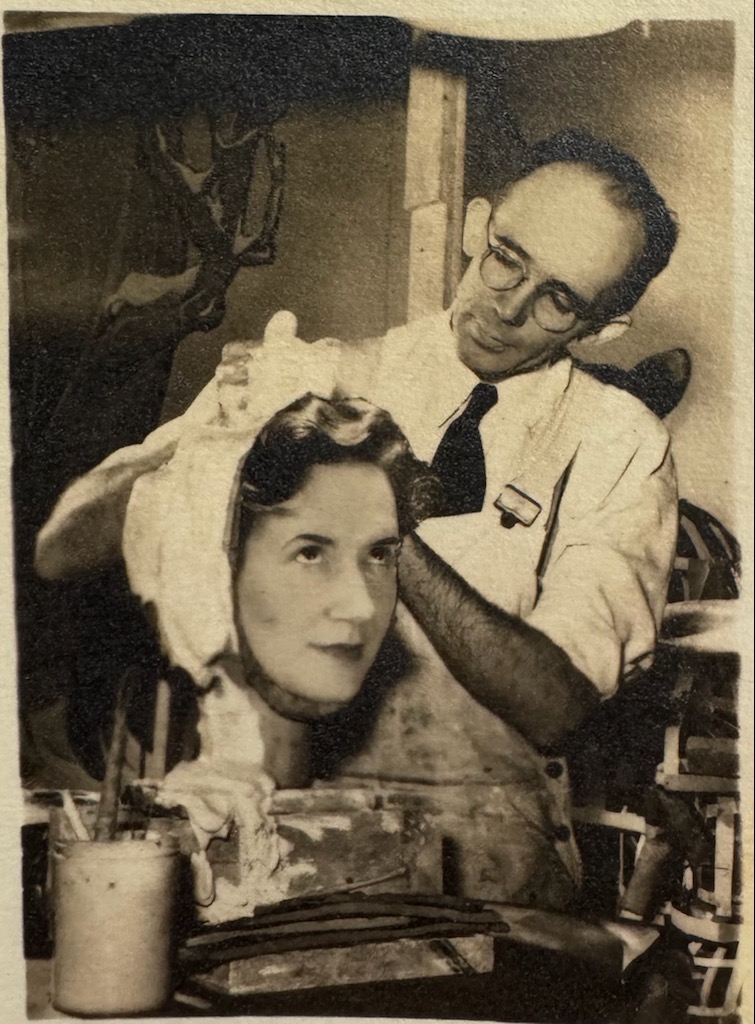

A 1962 Billings Gazette profile of Hockaday, headlined “Artist With a Cherry Orchard,” reported that he was born in Little Rock Arkansas, and when he was 18 his parents moved to Lakeside and started one of the first orchards on Flathead Lake in 1910. Hockaday enrolled in the St. Louis School of Fine arts in 1917 and went on to study for four years at Washington University in St. Louis before eventually establishing his own commercial art studio in St. Louis where he worked for the Scruggs, Vandervoort and Barney department store to furnish them with murals, and animatronic and sculpted displays to attract customers.

Calling him “A modern day ‘Geppetto,’” The Gazette described him as designing and making mechanical art installments, in addition to his other work as an artist. Some of his mechanical dioramas are still encased in glass and on display at Wall Drug Store in South Dakota.

Hockaday Quinby said that her grandfather died the year before she was born, but that her grandmother, Ethel, who was a seamstress and artist in her own right, worked hard to keep his memory alive, so that she and her brother could know where the family came from.

Hockaday Quinby still has photos of many of his animatronic displays and art work, and also has some of his art pieces and photographs. Hugh Hockaday was also a charter member of the Lakeside Chapel, and was involved in its architectural design and construction. His granddaughter said his initials are still in the church’s clock tower. As she recalled, her grandfather’s work as a commercial artist also involved doing the lettering for “The Phantom” comics, which were the creation of two other St. Louis artists. He moved back to the Flathead to take over the family’s ranch, before eventually returning to his work as an artist, which included designing animatronics and sculptures displayed across Montana, including for the Bovey family in Virginia City, but also in local venues, like the KM Department Store.

“It was a lovely memorial to him and I’m glad we got to have it for as long as we did to remember his legacy,” Hockaday Quinby said of the Kalispell art museum.

“The art community was super important to my grandparents, and they tried hard to get people involved and to teach art, and to help them learn to love art in various ways.”