Call of the Wild Woman

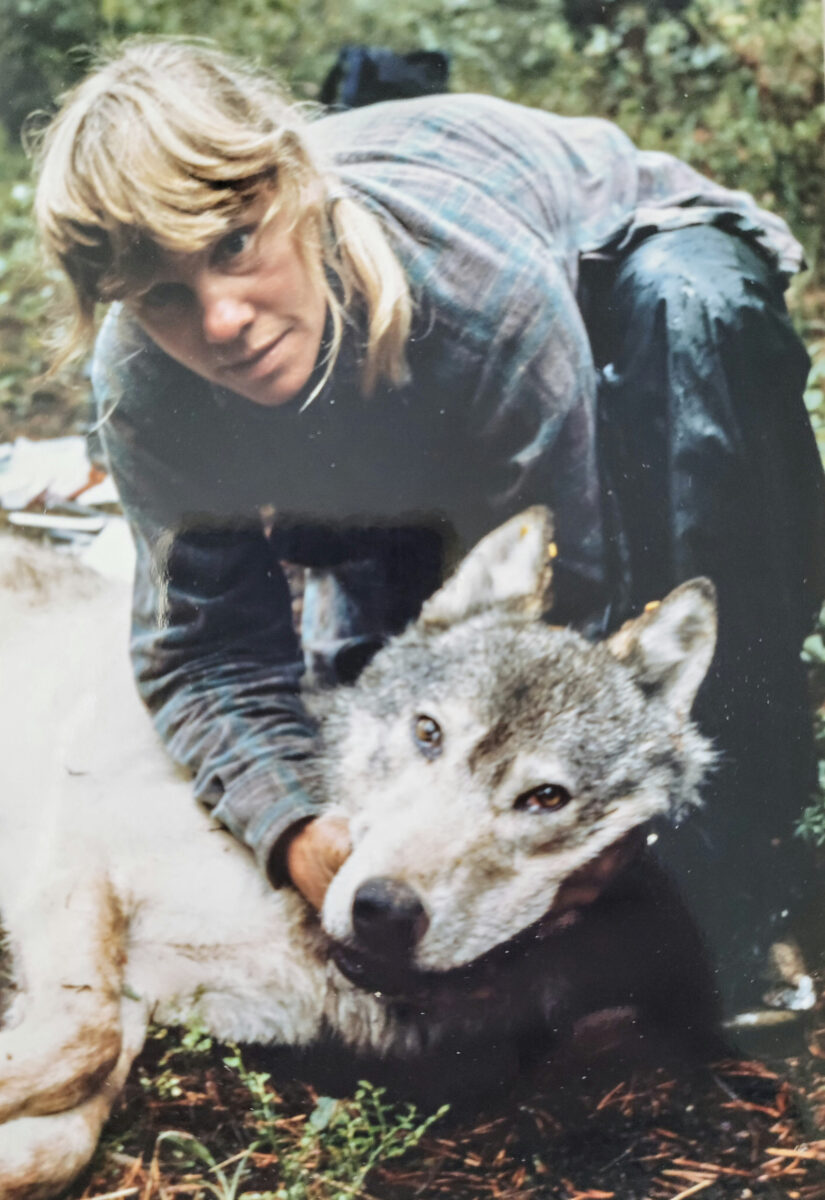

Longtime wildlife biologist Diane Boyd has been howling about wolf recovery on the doorstep of Glacier National Park for 45 years, often in the face of public misperception and resistance. Now, having recorded her journey in a book that’s receiving international attention, the “Jane Goodall of Wolves” is telling her story for the first time.

By Tristan Scott

During the four decades Diane Boyd studied wolves on the doorstep of Glacier National Park, tracking the “magic pack” and its offspring as the species migrated from Canada to naturally recolonize the western U.S., the term “wolf management” never struck her as a fitting job description.

“It was more like people management,” Boyd said. “And I haven’t always been great with people.”

To be fair, people haven’t always been great with wolves — or with wolf managers like Boyd. In her role as a wolf management specialist for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP), she was especially attuned to the anti-wolf sentiment on Nov. 28, 2018, when she arrived at the Lakeside Resort conference center in Trout Creek and couldn’t find a parking spot.

“Every square foot of asphalt for a quarter mile was packed with pickups sporting bumper stickers that read ‘Wolves, smoke a pack a day’ and ‘Save 100 elk, kill a wolf,’” Boyd recounted in her new book, “A Woman Among Wolves: My Journey Through Forty Years of Wolf Recovery,” which was published in September 2024 by Greystone Books. “Normally, Trout Creek is quiet in the offseason, but on this November night an angry mob had gathered to vent about wolves.”

In the hotel conference room crowded with “camo-clad, sidearm-packing” sportsmen and featuring an open bar, Boyd and her colleagues were greeted with a chorus of “boos,” their agency insignias betraying them as the targets of the audience’s ire. The hunters were mad, they said, because they believed wolves were responsible for decimating deer and elk populations, a theory the biologists refuted with scientific evidence. Although Boyd recalls it as “the only public meeting I have attended where I thought it was possible that someone could get shot,” Boyd kept her cool until she was confronted with the oft-repeated falsehood that wolves were reintroduced in northwest Montana. Bristling at the rumor, Boyd “told the crowd that the wolves in northwestern Montana walked down here from Canada on their own.”

“I knew because I was there,” Boyd said, according to her telling in the book.

To be clear, Boyd doesn’t dislike hunters, and believes that a successful wolf management program should include a hunting season with fair-chase policies and a sustainable harvest limit.

“I believe if we’re going to promote social tolerance, a hunting season should probably be part of the equation,” she said.

But when Boyd showed up to a mostly wolf-less Montana in 1979, the social tensions on display in Trout Creek three decades later hadn’t yet emerged — or at least, they hadn’t intensified to the degree they have today. Wolves were unique, almost mythical, and did not yet occupy the white-hot core of a political debate about their management.

“They had been gone so long, there wasn’t the hatred,” Boyd said of a species that humans had effectively eliminated by the 1930s through hunting, poisoning and habitat loss. “It’s been an amazing evolution of cultural perspective.”

Though wolves had been extirpated statewide, reports of sightings and shootings started trickling in during the 1960s and ‘70s, leading University of Montana professor Bob Ream to launch the Wolf Ecology Project in 1973, the same year that Northern Rocky Mountain gray wolves were listed under the Endangered Species Act. Having enrolled in the University of Montana’s wildlife biology graduate school, Boyd joined Ream in September 1979, assigned to an off-the-grid cabin along the North Fork Flathead River near the Canadian border as a self-described “starry-eyed waste-length blonde-hair hippie wolf-hugging lady.”

“I was a bit enamored with wolves,” she said.

Soon, she’d become enamored with one wolf in particular.

Earlier that year, on April 4, 1979, a researcher with the Wolf Ecology Project trapped a female wolf, dubbed Kishinena, in the North Fork drainage along the northwestern edge of Glacier National Park. Funded by multiple federal and state entities, Boyd, Ream and Mike Fairchild, another biologist, would spend the next three years tracking Kishinena’s movements.

Working diligently, Boyd observed Kishinena’s movements from a distance, so as not to disrupt the wolf’s natural behavior, tracking the radio-collar signal on foot or in her pickup, by skiing or snowmobiling in the winter, and by aircraft. She plotted the findings on a map and learned that Kishinena and a three-toed male had a litter of seven pups. At some point, something happened to Kishinena and Boyd lost her radio-collar signal, although another female wolf, Phyllis, assumed her position in the pack, which by 1986 began denning in Glacier National Park just north of Polebridge.

It marked the first time in a half-century that wolves had denned in Glacier Park, according to records.

“And that was the Magic Pack,” Boyd said. “These wolves walked down from Canada on their own and they recolonized the area. They were not brought here, they were not dumped out of trucks, they were not reintroduced here. They are incredibly resilient.”

From a formal scientific standpoint, the story of gray wolf recovery in the western U.S. starts with Kishinena, and nobody is better suited to tell it than Boyd, who would study and live among wolves, beginning with Kishinena and her descendant “magic pack,” for the better part of two decades, mostly without running water or power, and at times without funding. As a veritable Jane Goodall of wolves, her work has been widely cited and led to national attention, with Sports Illustrated profiling her in a 1993 feature entitled, “The Woman Who Runs with the Wolves.” In 2019, Boyd retired from a 40-year career spent studying wolves, both for FWP as well as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Yet in all those years running with wolves, Boyd never had the opportunity to tell the story herself. Until now.

“This has been my life’s work and there’s no one else to tell the story,” she said in a recent interview. “Bob Ream, Mike Fairchild, those guys are both dead. And now I’m retired so I had the time. The whole story of wolves in northwest Montana has not been told. There are hundreds of books about Yellowstone wolves, but our work in northwest Montana didn’t get much attention. And the wolves did really well here. Way before wolves were ever reintroduced in Yellowstone, we had eight packs of more than 70 wolves. My motivating factor was to tell the story. I wanted people to understand what it was like when they were coming back under their own power without fanfare and without assistance.”

Following the publication of her book, Boyd embarked on a promotional tour that included appearances on The Joe Rogan Experience Podcast, which boasts approximately 11 million listeners per episode, as well as the top-ranked MeatEater Podcast with Steven Rinella. In both wide-ranging interviews, Boyd seized the opportunity to set the record straight, pushing back on another common myth rejected by consensus science — that wolves are decimating deer and elk populations in northwest Montana, leading to below-average hunter harvests. Confronted with the misperception by Rogan, Boyd pointed to research showing that mountain lions are the top killer of both elk and mule deer, while moose are dying in greater numbers due to tick-born disease, particularly as the region’s winters become milder, allowing ticks to survive the cold and spread illness.

“I think one of the things people like about my book is I’m the same person sitting at my hosue with my dogs at my feet as I am on a podcast with millions of viewers,” Boyd said.

After returning to her home in the Flathead Valley, Boyd attended a forum hosted by the Whitefish Review, a local literary journal. Hosted by several moderators, the panel included Michael Jamison, a journalist and conservationist who as an undergraduate studied with Ream, the architect of the Wolf Ecology Project at the University of Montana.

“He told us there was this crazy wolf woman living up the North Fork, and we were going to go visit her and wade some rivers and ski a few miles and howl at wolves,” Jamison said. “I went up and met Diane and we howled at some wolves and the wolves howled back, and we skied quite a few miles and got colder than we probably should have. And then I was smart enough to go back home. But she stayed. It’s pretty remarkable now to see her come out of the hills and into town with all these tales to tell.”

Despite her familiarity with anti-wolf attitudes, Boyd said she’s surprised by the enduring social intolerance surrounding wolves, particularly as evidence shows that mountain lions and grizzly bears are responsible for more depredation of deer, elk and livestock than wolves.

“You can talk to sportsman groups, hunters and ranchers, and you can tell them about all this data, that there’s three times more mountain lions in northwest Montana than there are wolves, but they still claim the wolves have killed all the deer and elk,” Boyd said. “I don’t know how better to reach people than to give them good information and science in a format that they can look at and grasp, but opinions still don’t match reality in a lot of cases.”

Twenty years from now, Boyd said she doesn’t expect those strong opinions to disappear. But neither will wolves. Although she’s confident wolves will remain on the landscape, she said they won’t occupy their historic range across nearly all of North America due to social intolerance. Rather, they’ll continue to fill in secure habitat and find “corridors of tolerance” like they found along the North Fork Flathead River on the outskirts of Glacier National Park.

“The good news is wolves are incredibly resilient in figuring out ways to keep rebuilding their population. But I think the most effective way to keep wildlife on the landscape is to create value for them. Right now, to most people, wolves have no value. None. As a matter of fact, they probably have a negative value, and when that happens there is no reason that people want them on the landscape,” she said.

“The future for wolves given all this is still pretty bright, and I am not just wearing rose-colored glasses,” Boyd added. “But social tolerance is the only way that we are going to have wolves on the landscape.”