‘The Voice of the Flathead Valley’: A Tribute to the Life of Legendary George Ostrom

Remnants of a bygone era fade with the passing of luminary George Ostrom, who died on Jan. 1 at age 96, but the memory of his compelling life remains ever vivid

By Zoë Buhrmaster

For George Ostrom, the word “bored” didn’t exist.

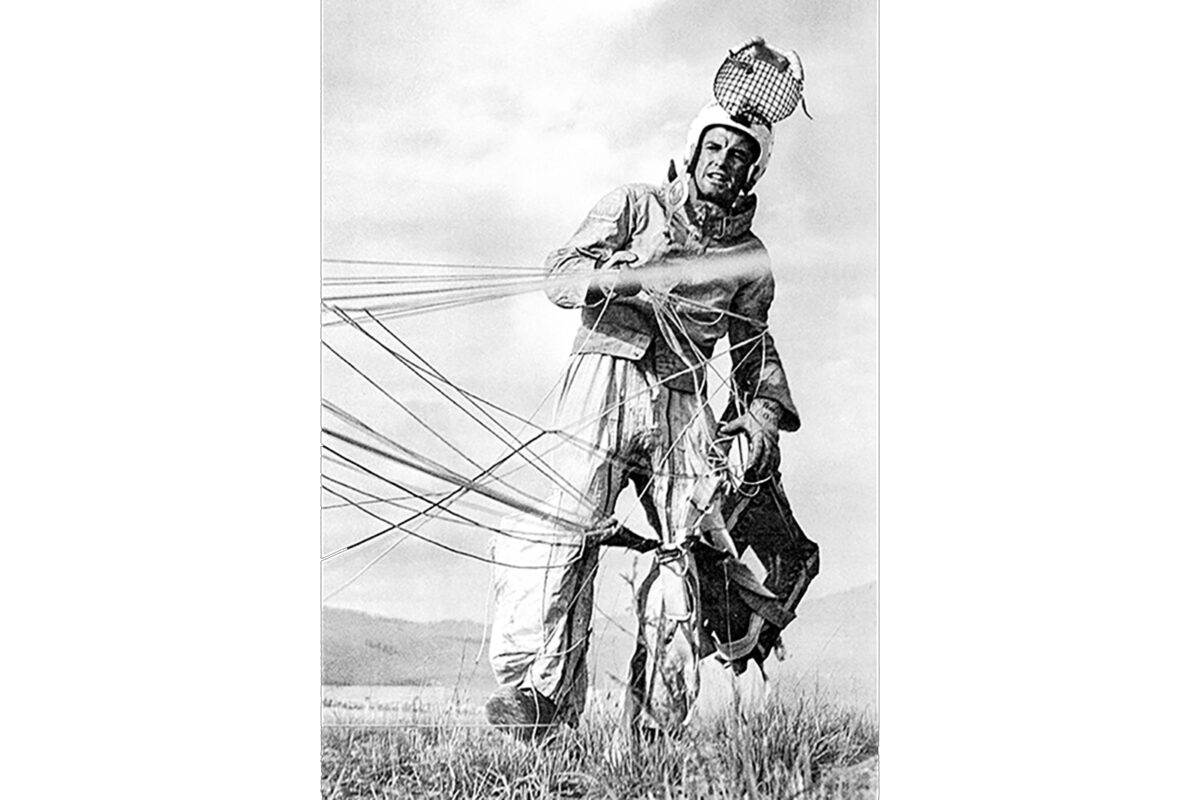

Between smoke jumping into the Bob Marshall Wilderness, greeting the Flathead Valley every morning as a KOFI radio announcer, starring as Richard Widmark’s stuntman in adventure film “Red Skies of Montana,” erecting the largest weekly newspaper in Montana, chasing down grizzly bear stories, helping compose the Wilderness Bill of ‘64, bagging peaks in Glacier National Park with his Over the Hill Gang, authoring four books, and fathering four children –– how could it?

Wendy Ostrom-Price, one of Ostrom’s two daughters, relayed the family idiom.

“There’s no reason to ever, ever be bored. You go read a book, you go paint a picture, you go write something, you do something. But that word was off limits in our household.”

Imagination for Ostrom came hand in hand with growing up during the Depression. While his father Logan joined the 1930s-era mining boom in the Flathead, young Ostrom would transform a rock in the yard into a truck, a ship, whatever the mind could conjure. When he saw an airplane in real life for the first time, he accurately predicted that he would get his pilot’s license and learn to fly.

He learned how to hunt to support his family and neighbors at the Flathead Mine homestead in the Hog Heaven district southwest of Kalispell. Only later as an adult would he trade in his gun for a camera.

As a high school freshman, Ostrom joined the Forest Service, fibbing about his age to become part of the bush crew, staying on as trail and fire crew. Isolated in his post at a fire lookout one summer, Ostrom would use the service’s single-wire phone line to call up high school buddy and fellow service member Ivan O’Neil, who would remain a lifelong best friend.

“He’d play his horn, and I’d play my radio,” O’Neil recalled.

Ostrom’s love for music would grow, eventually leading to him playing the piano, trumpet, guitar, ukulele, alongside the accordion and trombone.

At 17, Ostrom smudged his age upward again and left Flathead County High to fight as a paratrooper in World War II, where he helped develop a communication system that guided Allied Forces across Europe.

Ostrom became a smokejumper, one of the Forest Service’s first, leading a squad for five years. A solo jump into the 1954 dedication of a Missoula center landed him close to the front stage, where Ostrom candidly struck up a hours-long conversation with then U.S. Representative Lee Metcalf. Later, Metcalf would invite Ostrom to Washington, D.C. to help write the Wilderness Bill.

Ostrom’s determination led him to the KOFI radio station where he convinced the owner to let him try out despite the lack of a job opening. The audition resulted in Ostrom’s voice on air, the beginning of a career in radio and print news production that would last for the next 60 years –– including eventually owning KOFI, where Ostrom would inform the public every morning “what the dingbats, wingnuts and evildoers were up to last night.”

With a knack for being in the right place at the right time, Ostrom became known for his authority on the lore of the Flathead, helping uncover the true story of trapper Slim Link’s death in John Fraley’s book “Rangers, Trappers, and Trailblazers,” and snapping fundamental photos which Jack Olsen used for “Night of the Grizzlies,” the definitive account of the tragic 1967 bear attacks that killed two young women in Glacier National Park.

“He was the voice of the Flathead Valley,” said Bob Brown, a local historian who served as the former Montana Secretary of State and a state senator. “You didn’t really feel you heard the news until you listened to George.”

Ostrom wouldn’t give up journalism until his late 90s, later in life writing a column as the “Hog Heaven Correspondent” for Pulitzer Prize journalist Mel Ruder’s Hungry Horse News – a tribute to his childhood homestead near the Hog Heaven mine and sixth-grade publication the Hog Heaven Gazette.

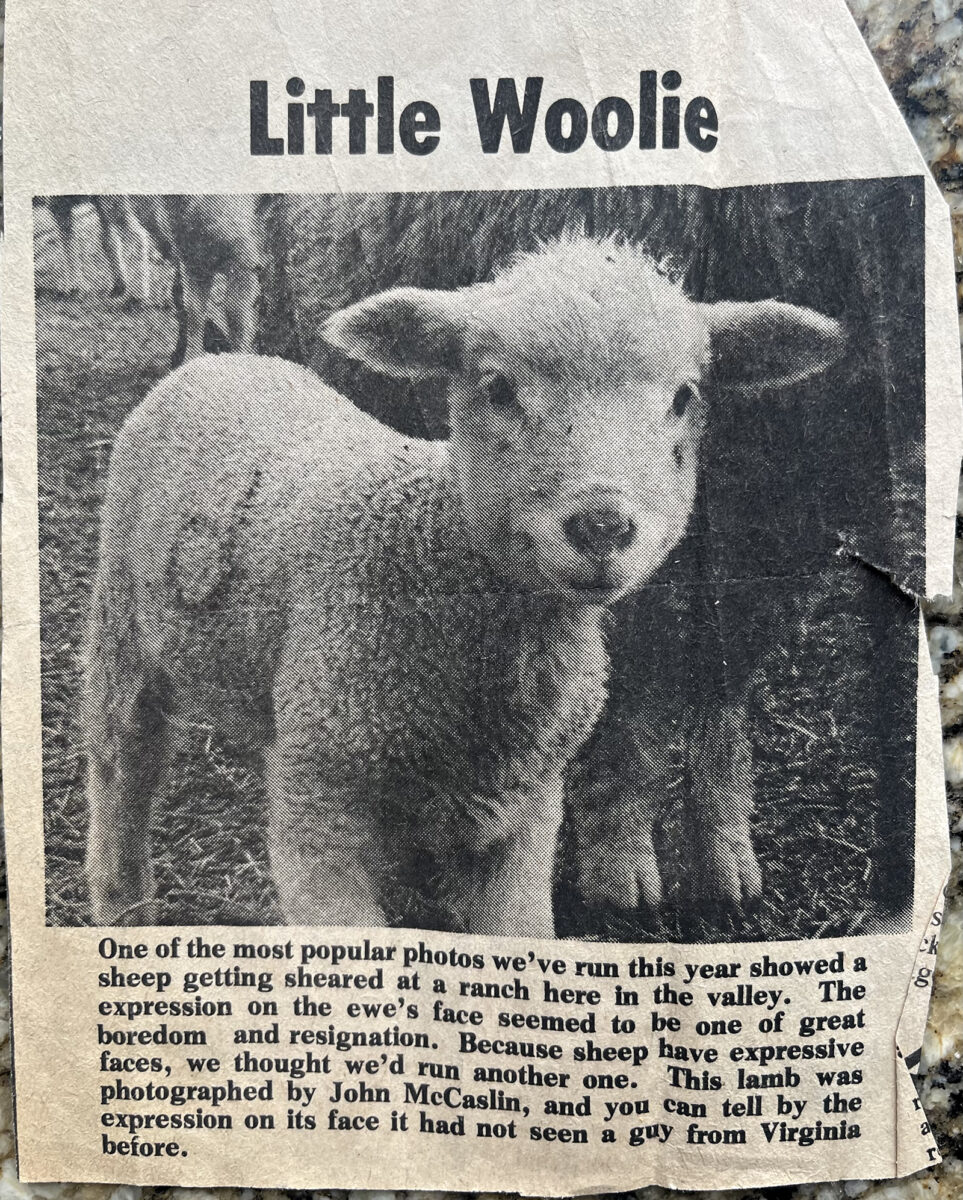

His proprietorship of Kalispell Weekly News in 1974 colored the pages just like his words on the airways, religiously weaving in humor with the facts by including a public divorces section titled “Split the Sheets” and, when someone died, explaining that “they’d gone to their final reward.” He prioritized the paper’s visual features, instilling in his reporters that “a good newsman sleeps with his camera,” said John McCaslin, a reporter for Ostrom who would go on to report for ABC News, NBC News, and as a White House correspondent for the Washington Times. “I remembered that the rest of my career.”

The publication became a family affair, with Ostrom’s wife Iris running circulation, daughter Heidi operating the press and daughter Wendy delivering newspapers. On “Wednesday Press Night” he recruited the children and their friends to fold newspapers in return for spending money and McDonald’s hamburgers.

“It all made us feel like we were doing something important and special,” Wendy said.

Ostrom’s family remained the pride of his life, touting his marriage to Iris Ann Wilhelm in 1957 as his smartest decision. He took their four children –– Shannon, Clark, Heidi and Wendy –– helicopter riding, mountain climbing, and skiing. When Wendy had nerves about an interview with some big shots early on in her journalism career, he informed her that “everyone puts their pants on one leg at a time. Don’t worry about them. Let them worry about you.” He sat back with pride when his daughter Heidi outshone his Hungry Horse News column in 1991 by winning first-place prize for humor in the Montana Press Association Awards. He held his grandchildren spellbound with stories from his past.

“My greatest accomplishment, what I’m proudest of, is my family,” Ostrom said. “That’s the thing that means the most to me.”

Ostrom died on Jan. 1, 2025, at the age of 96. with his best friend O’Neil at his side retelling stories from the past.

“I just think he’s done all the adventures here and he was ready to move on to the next thing,” Wendy said in an interview after her father’s passing. She paused and softly chuckled to herself. “I think maybe he finally got bored.”