As Glacier Park Prepares to Update 22-year-old Fire Management Plan, Officials Seek Public Input

Park officials are seeking feedback on an environmental assessment to a long-term fire management plan last updated in 2003; comments will be accepted through March 12

By Tristan Scott

A lot has changed since Glacier National Park last updated its wildfire management plan 22 years ago, including by ushering in more than two decades of fire history that’s transformed the landscape. And yet, because Glacier’s relatively intact mountain ecosystem has been preserved for more than a century — as a park, a biosphere and as a proposed wilderness area — much remains undisturbed.

The same can be said for wildland fire management policies themselves. The guidelines, directives and accepted wisdom have evolved over time, even as the overarching mission charts the same narrow course: to make firefighter and public safety the highest priority of every fire management activity.

But other values have emerged, too, competing for attention and priority in the park’s hierarchy of needs, while conditions in and around Glacier Park have been altered at an accelerated pace due to the effects of the climate change.

In an effort to ensure the proposed plan’s objectives align with those evolving priorities and changes, fire managers are seeking public input on how to achieve a range of objectives, including promoting conditions that maintain fire-resilient landscapes in a warming world, as well as protecting natural and cultural resources, including federally listed species, as well as ethnographic resources through engagement with tribal neighbors on the Blackfeet Nation.

As Glacier’s administrators prepare to modernize the park’s fire management guidelines for the next 20 years, they’re looking to reconcile outmoded elements of the existing plan with current policies and principles, while also adopting measures to reduce hazardous fuel loading using prescribed fire and other treatments, according to Jeremy Harker, Glacier’s fire management officer.

“Things have changed a lot since 2003,” Harker, who’s leading the effort to update the plan, said in an interview. “But I’d also go back to what hasn’t changed. Looking back on 20 years, we found that we are approaching fire very much the same way, no matter where it lands, and that comes from a risk-management point of view.”

In early 2003, the last time Glacier refreshed its park-wide wildfire management plan, it was still months away from encountering the most infamous wildfire season on record, which also ranked as one of its riskiest. In late July, a series of large, fast-moving fires torched 136,000 acres and threatened to overrun Apgar Village, West Glacier and park headquarters, as well as the remote Granite Park Chalet, where guests and hikers survived the blaze by sheltering in place. The fire burned right up to and around the chalet, but the building was spared and nobody was injured.

Fourteen years later, the Sperry Chalet could not escape the same fate when the Sprague Fire burned about 17,000 acres on the south side of Lake McDonald. Although there were no serious injuries, the Sprague Fire gutted the historic building’s dormitory (since restored) and devastated its throngs of perennial visitors who mourned the loss of an historic icon.

Indeed, the 2010s brought dramatic fire years in 2015, 2017, and 2018. In 2015, the Reynolds Creek Fire burned about 5,000 acres on the north shore of St. Mary Lake, including the historic Baring Creek cabin, and the Thompson Fire burned 18,000 acres in the remote southern portion of the park. One year after Sperry Chalet burned down, the 2017 Howe Ridge Fire burned nearly 15,000 acres along the north shore of Lake McDonald, including significant overlap with the 2003 Robert Fire footprint.

While 2003 will forever be remembered as the year of the Robert Fire in Glacier National Park, it also signaled an inflection point for wildland fire management on a national scale as agencies overturned the conventions of fire suppression that characterized fire management tactics for decades. After decades of suppression-at-all-costs tactics, fire management polices had shifted, allowing fire to play a more natural role on the landscape while still prioritizing human health and safety and the protection of private property and public infrastructure.

But the new “fire culture” had shortcomings, too, Harker said. Terms like “fire use” and “fire for resource benefit” are “terms we don’t use anymore,” he said.

“The idea back then was that we would set aside remote areas of the park where we thought fires would take very little suppression action,” he said. “We found that was a very difficult measure to come up with. We respond to every single fire with some management action, and our response to every single fire is determined by the first question in our risk-based decision-making criteria: How much risk is there to responders and aircraft, and what values are out there that could put people at risk?”

For Harker, the proposed updates to the park’s management plan synthesizes and simplifies the evolution of the fire-management paradigm. It also provides an opportunity to showcase this more nuanced approach to wildfire management as the park records and monitors the ecological benefits of fire and the complexities of climate change.

Emphasizing that the proposed plan is an update, and not a policy overhaul, Harker said many elements of the 2003 plan have been updated on an annual basis since its official publication through 2024.

“Right after we published the existing plan in early 2003, we promptly burned a lot of acres, which led to some immediate changes to the plan going way back more than 20 years ago,” Harker said. “It has stayed current with policy changes. But some of the framework of the 2003 plan was beginning to sound irrelevant.”

By pivoting away from identifying the resource objectives of wildfire, Harker said, the agency’s new management plan centers its focus on management objectives and resource outcomes.

“We acknowledge that wildfire is often a great benefit on the landscape,” he said. “But it’s an outcome rather than a management objective.”

Still, the updated plan provides guidance on the use of prescribed fire and non-fire fuels treatments to protect human health and safety as well as to “reduce hazardous fuel loading and accomplish resource protection objectives.”

While prescribed fire could occur in other areas of the park, under the current multi-year treatment plan, prescribed fire (broadcast burning) is expected to be implemented in the North Fork District within ponderosa pine stands at Sullivan Meadow and grassland areas in Big Prairie. The purpose of these prescribed burn treatments would be to maintain the ponderosa pine stands and open grasslands as a continuation of maintenance that began in the 1990s. Prescribed burn treatments are currently anticipated for a total of approximately 400 acres of grassland and approximately 150 acres of ponderosa pine over the next five to 20 years.

“Most of our fuels reduction is prioritized around infrastructure,” Harker said. “We have 864 assessed structures around the park and a lot of them need fuels maintenance or fuels reduction. Larger landscape-level projects or the precommercial thinning we see the [Flathead National Forest] carrying out, that’s more difficult to implement because it contradicts our mission to preserve the park unimpaired for generations.”

All fuels reduction projects and prescribed burns would be subject to environmental review and compliance, according to the proposed plan.

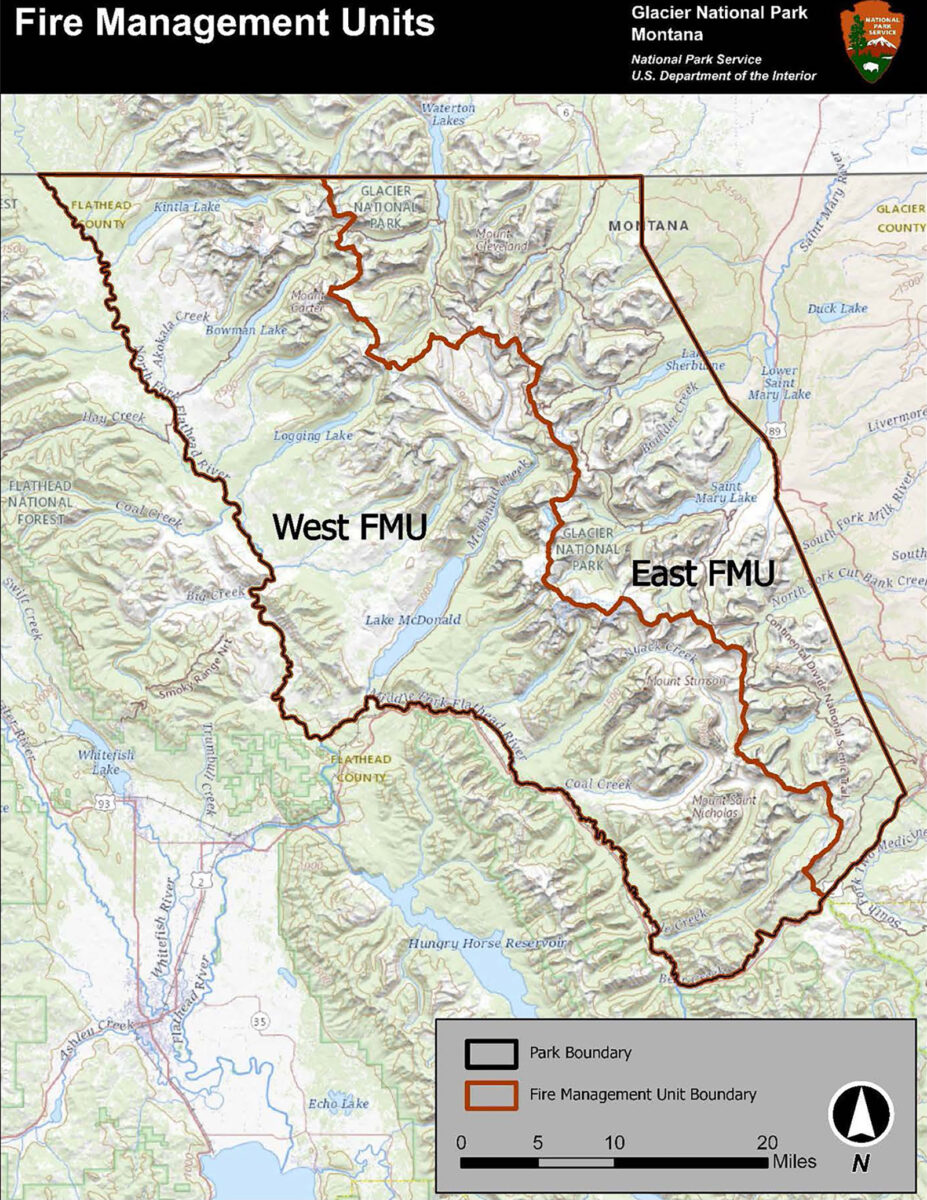

Under the updated fire management plan, Glacier would be divided into two fire management units (FMU): The West FMU is made up of all land within Glacier west of the Continental Divide, while the East FMU constitutes all land within Glacier east of the Continental Divide.

Although the majority of Glacier’s fire starts have historically occurred in the West FMU, Harker said fires on the east side are more challenging, both due to their topographic complexity as well as their geographic proximity to “values at risk,” including the Blackfeet Nation communities that share the park’s eastern boundary.

“We do have more occurrences of fire on the west side, but our drainages on the east side all run up through the Continental Divide and our fires tend to spread in that direction where there are more values at risk. Fires on the east side are harder to deal with, harder to respond to and harder to manage in the long term,” he said. “Fires that get big on the east side are a big deal.”

The plan also emphasizes the need for education and outreach, which Harker said is critical toward building awareness about wildfire prevention, as well as social tolerance.

“Public sentiment on fire management is one of our biggest challenges and one of our biggest tools that we have is education,” he said. “If we can instill in the public a favorable view of wildfire on the landscape then we have an easier time managing fire, whether that’s through fuels-reduction work or getting people accustomed to seeing smoke for a couple weeks on the landscape.”

Harker said the communities of residents along the North Fork Flathead River, including around the park’s Polebridge entrance, serve as a prime example of a “fire-wise” community.

“The North Fork has come a long way,” he said.

As required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the park’s proposed fire mitigation plan has undergone an environmental assessment. The next step is a public scoping period aimed at evaluating how the plan will affect a 1-million-acre landscape whose ecological health and cultural value has been shaped by centuries of wildfire.

The environmental assessment was completed earlier this year. A 30-day comment period that began on Feb. 10 continues through March 12.

For an interactive map of Glacier Park’s fire history, visit the fire history page on its website.