In the modern world, light is about as omnipresent as air. Car headlights, streetlamps, and oh-so-many screens shine around the clock. Our history of making light may go back as a far a million years, when members of Homo erectus, “the first humans,” experimented with making fire. But manmade photons did not shine in true abundance until the furnaces of the Industrial Revolution unleashed a luminous technological tsunami upon us.

From the oppressive flicker of fluorescent celling fixtures in office buildings, to the eerie orange glow of a halogen streetlight in a quiet alley, non-natural light affects our psyches and physiology on both a conscious and unconscious level. On the plus side, light on demand mitigates the dangers inherent to darkness and enables all manner of travel and other activities after the sun has gone to bed. The costs come in the forms of chronically disrupted circadian rhythms and enhanced eyestrain. Not to mention nightly, soul-filling glimpses of the stars in all their glory are no longer a given for billions of people.

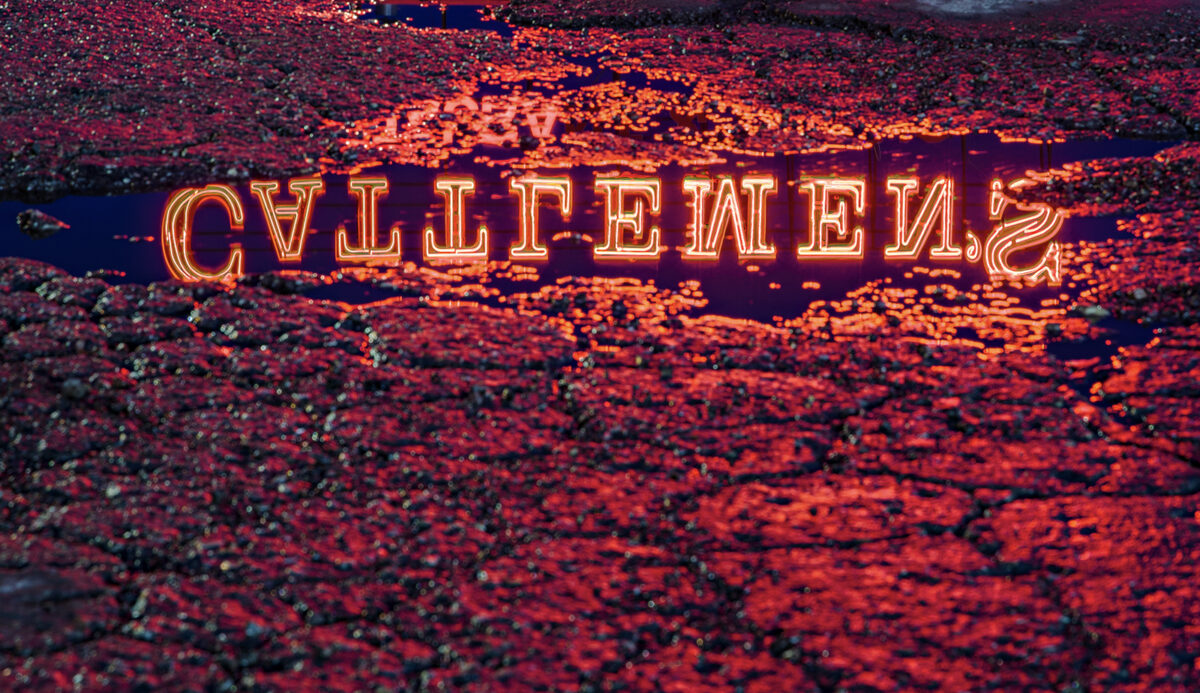

Neon light, and its contemporary LED imitators, are perhaps the most nuanced of all artificially generated illumination. Neon runs the mood gamut, ranging from the welcoming wavelengths emitted by a small “OPEN” sign in the window of one’s favorite hole-in-the-wall restaurant, to the garish glow of the Las Vegas Strip or Times Square.

Blessedly, Montana remains a place where natural light mostly still prevails. However, no urban nightscape, no matter how modest, is quite complete without a touch of tubular luminescence, including around Kalispell, the state’s seventh most populus municipality.

Some of this light has disappeared with the establishments they once advertised. Others shine on.