One Year After a Local Paddleboarder Disappeared on Hungry Horse Reservoir, a Community Tries to Make Sense of the Loss

Emily Rea’s disappearance has led to a range of theories as her family and friends cope with the uncertainty and ambiguity surrounding the case as the search continues

By Maggie Dresser

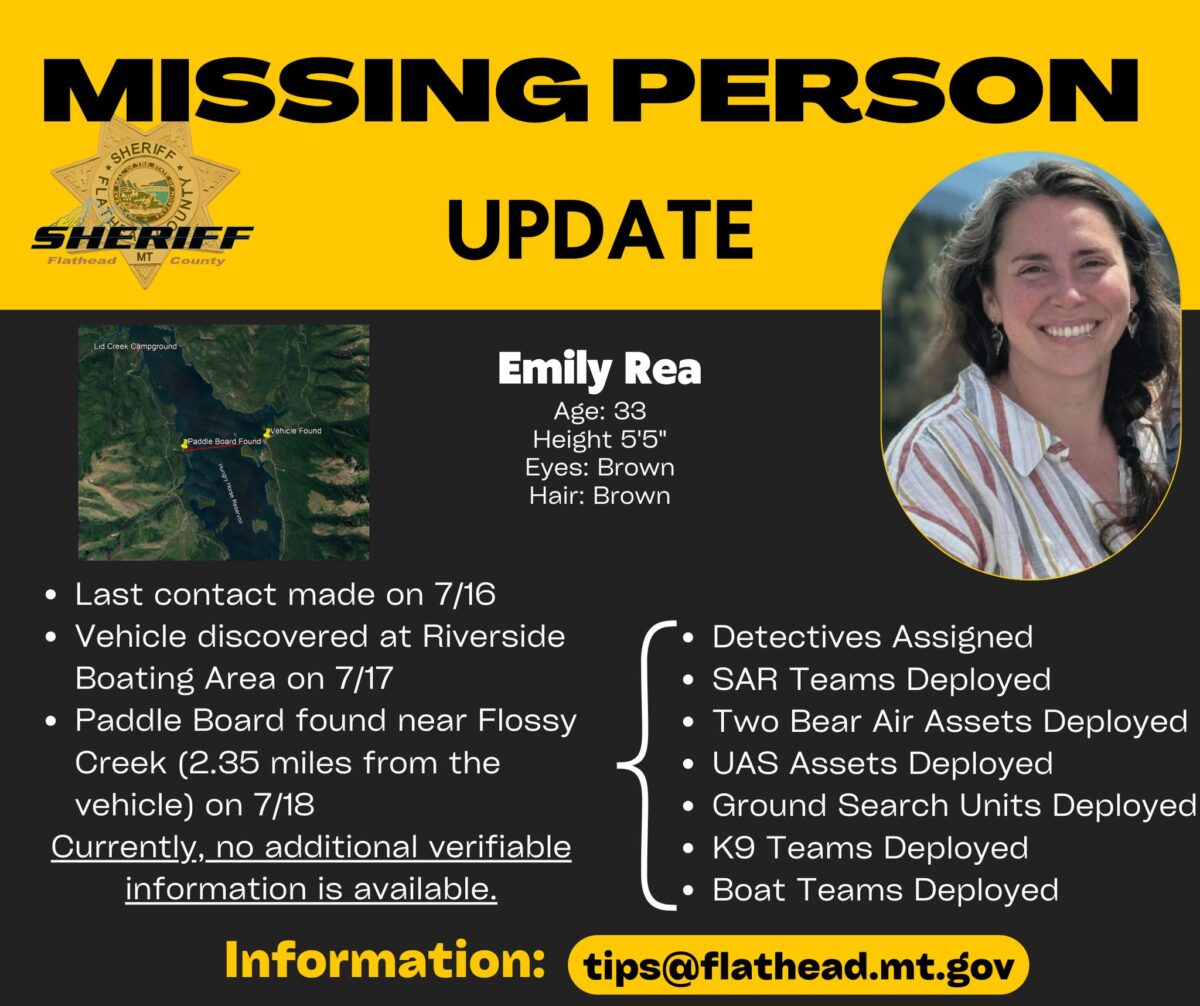

Last year on July 16, 33-year-old West Glacier resident Emily Rea drove her black Honda CRV up the South Fork Road 21 miles to the Riverside Boat Launch on the east side of the Hungry Horse Reservoir for what law enforcement officials believe was an evening of solo paddleboarding on a hot summer night.

The following day, her employer at The Skola, a nature-based school, noticed she didn’t show up to work, which was unusual for Rea. She was, by all accounts, a responsible employee who also helped her boss manage vacation rentals in the summer. She called Emily’s mother, Nina Rea, and the Flathead County Sheriff’s Office (FCSO) launched a search and rescue (SAR) mission soon after. Nina flew out of Atlanta later that night.

As the search ensued, officials began gathering information from cell phone data and camera footage, which showed her CRV at the boat launch after 8:30 p.m. and her cell phone last pinged at a cell tower near Martin City before she lost service.

After Emily’s vehicle was found at the Riverside Boat Launch on July 17, search crews found her paddleboard on the other side of the reservoir near Flossy Creek, about two miles from her vehicle, the next day. The location was consistent with the westerly wind that was blowing on the night she disappeared, according to authorities. Her paddle was stowed and assembled on the board. Her life jacket and cell phone were never found.

Over the next two weeks, search and rescue teams, Two Bear Air rescuers, drone teams, ground teams, divers and multiple sheriff’s offices and other government agencies spent more than 1,800 hours searching for Emily. Officials deployed K9 teams, remotely operated vehicles (ROV), and boats equipped with sonar in attempts to find her.

A year after Emily’s disappearance, authorities still have not located her, and Flathead County Sheriff Brian Heino has since focused efforts on water recovery.

In addition to ground searches in the terrain surrounding the reservoir, sheriff’s office deputies have also followed up on tips from psychic mediums called in by some of Emily’s friends. One psychic saw Emily in the Izaak Walton Inn vicinity located on the other side of the Flathead Range from the reservoir. Another tip took law enforcement 32 miles south to Spotted Bear. The extended searches yielded no evidence that she was there.

“We checked some locations,” Heino said. “We had a lot of public input into different things and there was a lot of pressure to check up on leads.”

In a matter of days, Emily’s best friend from college, Michaela Schwartz, launched her own campaign from the East Coast to find her. “Missing” posters were soon plastered all over the Flathead Valley and a loyal army of friends and coworkers assembled to search for her.

When Nina called Schwartz to tell her Emily was missing, she seamlessly shifted into an unofficial communications center to help Nina deal with the nonstop phone calls, texts and emails. She started a Google Doc and created a Facebook page to update friends and family about the situation. Eventually, she launched a website called “Eyes for Emily” dedicated to the latest updates and information.

“It was mostly updates,” Schwartz said. “I would also get random things like, ‘oh have you thought of this?’ I got that a lot, and I passed everyone along to the right people.”

Schwartz was glued to screens from her home in Massachusetts during that first week after Emily disappeared, communicating with her loved ones and passing along information to the appropriate authorities during a week she already had taken off from work because of a planned vacation that she did not go on.

“Reflecting back, it was kind of scary,” Schwartz said. “There’s a picture of me with three different laptops and I’m on my cell phone. For me, it was coping. It was how I was able to process it. I can either be a complete wreck, or I can channel all of my energy into this thing I can do well.”

Meanwhile in the Flathead, crews continued searching and Emily’s friends mobilized for their own searches separate from the authorities.

Hannah Plumb, a friend of Emily’s, said she drove up and down the east and west sides of the reservoir throughout the summer. She hung up posters. She boated around the reservoir, stopping at inlets and yelling her name. She met with Emily’s uncle once a week on Zoom, and she continued searching until the snow started to fall.

“It consumed the bulk of my summer,” Plumb said.

Sheriff Heino said a high volume of Emily’s friends searched for her, which he said is common in missing persons cases. In his two decades in law enforcement, Heino said missing people trigger emotional reactions from loved ones and, while help is appreciated, the intense scrutiny can lead to rumors.

“People attach to these things very quickly,” Heino said.

After extensive ground searches were conducted around the Hungry Horse Reservoir last summer, Heino has since focused efforts on water operations. But many of Emily’s friends and family members believe there was foul play involved in her disappearance.

“From the get-go, we’ve been so appreciative and impressed with the amount of work the sheriff’s office has done in and out of the water,” Nina said. “They fully believe it was simply a paddleboard accident.”

But Nina is looking at all possible avenues to find her daughter. While she’s not ruling out a drowning, she says the circumstances surrounding Emily’s disappearance don’t add up.

How did a smart, independent outdoorswoman who spent 12 summers salmon fishing in Alaska drown while out for a casual paddleboard mission on the Hungry Horse Reservoir? Why are her cell phone and life jacket still missing? Why was her paddle strapped to her board? Why was she out that late at night?

“There are a lot of questions that we don’t have the answer for — why was the paddleboard like this or that? It’s difficult because we don’t know. We don’t have the information, and we can’t talk to her,” Heino said. “You can’t answer those questions. There are paddleboard drownings all over Montana and what we see is paddleboards get away and they try to get to them but can’t.”

While Emily’s case remains an open investigation, her family has pressed for a deeper criminal investigation. But Heino said there is no evidence that suggests there was any foul play. Her car revealed no signs of a struggle. He received no statements that anyone was heard screaming. Ground searches revealed nothing.

Emily also didn’t fit the profile of the typical kidnapping or sex-trafficking victim, Heino said. Most victims the sheriff’s office deals with are involved in drugs. Emily was not.

Nina has requested access to Emily’s laptop in hopes of finding information that could point them in the right direction in case she was the victim of a crime. But without the password, it’s been sent to federal agencies to unlock it, which could take years. Cell phone data that showed Emily’s proximity to cell towers were recovered; however, text messages could not be recovered due to privacy laws.

Although Nina is frustrated that law enforcement has not pursued a criminal investigation further, she understands the sheriff’s office has exhausted its resources. To illustrate the scope of Emily’s support network, Nina has collected more than 5,000 signatures in a petition at change.org, which she submitted to Montana Attorney General Austin Knudsen in hopes that his office will investigate it. She also recently hired a private investigator. This spring, Emily’s supporters held a rally in Whitefish to raise awareness and funds to benefit her search.

“The search will come to a natural end,” Nina said, referring to the official search conducted by public agencies. “It would be unconscionable to continue to ask others to help us forever and ever. But I will never lose hope. I will never stop looking.”

While Nina is not convinced that Emily drowned in a paddleboarding accident, she’s also not ruling it out, despite the volume of resources that have been expended on the water search.

Emily’s family last summer reached out to Gene and Sandy Ralston, a couple based outside Boise, Idaho, who travel around the world using their side-scanner sonar equipment to help search for drowning victims at no cost.

“Typically, families contact us when law enforcement has done all they can,” Gene said. “Often times, law enforcement agencies have their own equipment, but they don’t have quite the depth capability we do because we have a heavier custom-made tow fish. We’ve searched as deep as 850 feet before.”

The sonar machine is towed up to 15 feet off the bottom of the boat and uses sound to create images on the bottom of a body of water, like an ultrasound inside of a body. It transmits pulses of sound, which reflect off the lake, river or ocean bottom, and software processes the reflection into an image. When bodies are located, they use a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) for recovery.

During their careers in environmental consulting, the Ralstons became involved in search and rescue and purchased their own side-scan sonar equipment in 2000. They have since recovered more than 130 bodies in depths hundreds of feet below the water’s surface. They have been involved in 25 homicide cases, including a 30-day search for Laci Peterson, whose husband was convicted of her murder after she disappeared in 2002.

In British Columbia, the Ralstons found the body of a man who went missing in François Lake 29 years before at a depth of 500 feet while they were searching for a different victim.

Twelve years ago, Cory Reeves of Great Falls lost his father-in-law when he drowned in Placid Lake just south of Seeley Lake. After a month of unsuccessful searches, his mother-in-law reached out to the Ralstons, who agreed to help. His body was recovered after four hours.

Reeves was on the boat during the recovery, and he remembers feeling a huge weight lifted when he heard Gene say, “We got him.”

“They do God’s work – I truly believe that,” Reeves said. “They bring so much closure to families.”

During the 32 days Reeves’ father-in-law was missing, he describes the emotional toll it took on his own family.

“It was hell for a month,” Reeves said. “Your mind starts playing games on you. You think, did he really drown? Did he get sick of the family? All these stupid things run through your head.”

After the recovery, Reeves started tagging along with the Ralstons to assist with searches and to help bring closure to other families.

Reeves has joined the Ralstons in two separate searches for Emily — the first last summer and the second in June 2025. He empathizes with Nina, sharing his own personal experience of searching for a missing relative.

“I told her, I didn’t have to go through it for a full year, but I know what it was like for 32 days without someone, and it is emotionally and physically draining,” Reeves said. “You don’t sleep well, you don’t eat well — and more than anything I wanted closure for my mother-in-law, my wife, his kids — those types of things.”

While the Ralstons have searched a variety of water bodies, they describe the search for Emily in Hungry Horse Reservoir as one of the most challenging.

In addition to the lack of information about where Emily was located, the reservoir bottom’s terrain is structured with submerged artifacts from before the Hungry Horse Dam was built in 1953, including a standing telephone line, the foundations of old buildings, and 8-foot-tall tree stumps. By comparison, natural water bodies like Flathead Lake have a clean, flat bed surface. Most of the areas that have been searched so far have a maximum depth of 270 feet in the 34-mile-long reservoir.

“Whatever was down there before the reservoir was filled is pretty much still going to be there,” Gene said.

Since Emily’s body has not floated to the surface — a process that happens in shallow water when the temperature is warm and there is less atmospheric pressure — search crews believe hypothetically that she’s in water deeper than 100 feet.

“If she was in shallower water, she would have surfaced, so we’re leaning toward searching in anything deeper than 90 feet or so with the current lake level,” Gene said.

After working on hundreds of searches over the years, Gene said the lack of clarity and the absence of a death certificate creates a stressful environment for families and “wreaks with their entire lives.”

In addition to the emotional toll, the search becomes financially draining as their lives become consumed with the search after local law enforcement agencies exhaust their resources. Other logistical matters, including legal affairs and sorting through personal property, exacerbate the unresolved nightmare. Without a body, insurance policies, bank accounts, and assets are frozen.

“A lot of people don’t realize that without a death certificate or a presumptive death certificate — which is sometimes difficult to get — all of the legal affairs of that individual is on hold,” Gene said.

When bodies aren’t recovered, Gene said friends and families of missing people often turn to other theories as a way to make sense of what happened.

“People think just because we can’t find somebody in the lake means that they’re not in the lake,” Gene said. “That’s not true. It would take a lifetime to do what we’re doing and cover the entire lake. Even if she were there and we didn’t find her for whatever reason, there’s always the possibility we have a (sonar) image of her or another person and we just can’t pick her out of the image.”

In Sheriff Heino’s 20 years in law enforcement, he has witnessed the deep and resounding impact that missing individuals have on a community when they are not recovered right away.

When Dr. Jonathan Torgerson, a well-known physician in Columbia Falls, went missing while solo backcountry skiing outside of the Whitefish Mountain Resort boundary in February of 2018, multiple search and rescue agencies along with swaths of community volunteers aided in the search.

Authorities were certain that Torgerson was killed in an avalanche, but a heavy snowstorm following the incident hindered search and rescue efforts. His body wasn’t recovered until May 12, 2018, nearly three months after he went missing, when a K9 team located him after enough snow had melted.

The recovery brought immense relief to Torgerson’s friends and family, despite the circumstances.

“It’s human nature to maintain a sliver of hope, no matter how illogical,” said Valerie Kneeland, a family friend of Torgerson’s. “But he is home. He’s not home the way we wanted him to come home, but for his family to finally have answers is immeasurable.”

While some families wait for weeks or months, for others the wait never ends.

In 2013, authorities eventually had to call off the search for a 65-year-old Kalispell man who they believe drowned in the Flathead River while duck hunting that October. The only trace left of the hunter was his overturned kayak and a paddle, which were recovered from the river south of Sportsman’s Bridge on Montana Highway 82 near Bigfork.

Resources that included search and rescue operations, a helicopter and side-scan sonar equipment were used in the mission, but Heino said there were some areas that could not be searched because of hazardous terrain.

“I remember when the duck hunter went missing,” Heino said. “The challenge was we had log jams the size of football fields in the river. I had to explain to the family that I couldn’t put my divers down there.”

Heino said the lack of closure can be devastating for families, and while his office is committed to utilizing resources to grant that sense of certainty, it’s not always possible.

“I think any time someone loses a loved one, you want answers,” Heino said. “In water operations, you don’t get that closure right off the bat. I can’t even fathom that uncertainty. We live in a remote part of the world and there are a lot of people who have never been found. They want answers, and we want to find these answers. They want closure — you try to do the best you can.”

Retired University of Minnesota professor, researcher, author and therapist Pauline Boss has worked with families of missing people for the last four decades and calls this type of loss “ambiguous” because of the uncertainty it defines.

“It’s the worst kind of loss,” Boss said. “Because all losses are difficult, and death is difficult — but you’re stuck. Your grief is frozen.”

Boss said different theories often emerge in the absence of facts. As with Emily’s case, law enforcement, family members and members of the community often do not agree upon where a missing individual is or what should be done.

“Because there are no facts and there’s no certainty to what is happening — it’s a crazy-making kind of situation where any theory could be true,” Boss said. “She’s coming back. She’s living in another town. She’s under the water. She’s dead. They go back and forth between hope and hopelessness. There’s usually conflict in the family that’s left behind.”

Family members of missing people suffer from unresolved grief and often have not accepted death. The environment becomes pathological, Boss said.

To heal from the trauma, Boss said stress therapy is the most effective tool to help people learn how to increase their tolerance of loss, and to try and identify its meaning, which she said is difficult to locate internally. Establishing a type of memorial can also be important to honor the missing person.

“Grief therapy does not work,” Boss said. “Because you can’t get them to accept that they’re dead. It’s very cruel for people to say, ‘Don’t you know they’re dead?’”

A year after Emily’s disappearance, paperwork consumes much of Nina’s days, which includes reviewing Emily’s bank accounts, bills and insurance policies. She’s unsure about when to permanently close her accounts or what to do with her personal belongings. Emily’s dog, Hugo, is living with a foster family.

At her home in Georgia, Nina, who is 67, walks by Emily’s bedroom and wonders if she’ll ever hear her daughter giggling in there again. She wonders if they’ll ever go on family trips or spend holidays together. She wonders if they will ever be reunited.

Growing up as an only child, Emily and Nina formed a tight bond. While Emily maintained a good relationship with her father following her parents’ separation, Nina said she and her daughter grew close.

“There’s a tremendous Emily void,” Nina said. “It’s not just the loss of a family member for me, but for a daughter that could have hardly been closer. We’re connected. We still are.”

Nina relies heavily on her Christian faith to stay connected with Emily, which she said helps her rise above the darkness. When she starts to feel empty, she prays.

“I’ve got voids and holes that need to be filled,” Nina said. “I could fill those with darkness, despair and doubt. I’ve seen what emotional stress can do to a person — that’s evil winning in my mind.”

Nina’s brother, Brian Sanders, has been part of her support network since Emily went missing. He has also been involved with search efforts and meetings with law enforcement.

“My heart completely breaks for her,” Sanders said. “Emily was an only child, and they were very close. I’m in awe of Nina in terms of her ability to put this into context — she has a very strong faith, and she leans into that faith as a way of dealing with this.”

“As an uncle, and as a brother to Nina, it’s just very difficult to make sense of this,” Sanders added.

Schwartz, too, is working to make sense of her best friend’s disappearance.

Friends since they met during their freshman year of college in 2009, Schwartz and Emily maintained a close bond from across the country as they grew into adulthood, talking once a week and texting most days. She describes complicated feelings of guilt surrounding the loss.

“For me, this is not the same as a death — it’s just not,” Schwartz said.

When the search paused last winter, Schwartz shifted from a high-alert state of mind and has since reevaluated the situation to help her process it. Her main goal now is to support Emily’s family, remaining in frequent communication with Nina while she continues to update the “Eyes for Emily” website as her family wishes.

While Nina has expressed immense gratitude for the sheriff’s office and the high volume of resources that has been expended to search for Emily, she wants to make sure no stone has been left unturned.

After recently connecting with a private investigator to take a deeper dive into Emily’s case, Nina plans to explore any tip that could lead to her daughter, even after the official search comes to what she calls a “logical end,” which she said will likely be this winter.

“I can come to terms and grips if there’s a finding that she is no longer walking this earth with us, and my peace comes with the loving arms of, who I say is, my heavenly father Jesus Christ,” Nina said. “What I cannot live with — what I could never put to rest, is if I did not do everything possibly human to find her.”

A ”Paddle Out” event will be held at Somers Beach State Park on Saturday, July 12 for Emily Rea.