What Could the End of the Roadless Rule Mean for Montana’s National Forests?

Critics of the decades-old policy restricting road construction and timber harvests in inventoried roadless areas say its repeal removes obstacles for local forest managers. But conservation advocates and former forest planners say the rule’s dissolution is more complicated.

By Tristan Scott

When U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins announced last month that the administration was taking steps to rescind a decades-old policy to restrict road building and timber harvests on 58.5 million acres of national forest lands, she justified it as another step by the Trump administration to remove “absurd obstacles” that have stymied forest management and intensified the threat of wildfire.

“Instead of protecting forests, it has trapped them in a cycle of neglect and devastation,” Rollins wrote, calling the rule “overly restrictive” and describing its repeal as conforming with President Trump’s initiative to accelerate the pace and scale of logging and fuel treatment, ramping up timber harvests and tamping down the threat of wildland fire.

Montana’s elected leaders celebrated the decision, with U.S. Sen. Steve Daines, R-Mont., calling it “another huge win for Montana and forest management.”

“By rolling back the outdated Roadless Rule, we’ll be better equipped to manage our Montana forests and protect our communities,” Daines said in a statement, pointing to data that 58% of National Forest System land is currently restricted from road development, “making it nearly impossible to be properly managed for fire risk.”

“Rescinding the Roadless Rule would allow for fire prevention and responsible timber production by removing administrative prohibitions on road construction,” according to the statement.

In northwest Montana, however, proponents of the Roadless Rule say that framing it as a barrier to active forest management is a mischaracterization, and that, while its value as a conservation tool is unmatched — in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, for instance, eliminating the Roadless Rule would remove critical safeguards against logging and roadbuilding across 9 million undeveloped acres — its genesis was born of utility and agency efficiency rather than an advocacy apparatus to obstruct.

Established under the Clinton administration and enacted in 2001, the Roadless Rule generally prohibits road building and logging in all 58.5 million acres of national forest roadless areas. It makes exceptions to access non-federal land inholdings and pre-existing mineral leases, and it allows some logging to reduce fire risk, improve habitat or aid in the recovery of endangered species, including whitebark pine. The primary thrust of the federal rulemaking initiative was geared toward reining in the scale of road-building activities by the Forest Service, which maintains eight times more miles of road than the Interstate Highway System.

The impetus for the Roadless Rule tracks back to 1998, when former U.S. Forest Service Chief Mike Dombeck saw the agency’s vast and poorly maintained road system as a major environmental and fiscal problem and proposed a temporary moratorium on road construction in inventoried roadless areas across most of the National Forest System. At the time, the agency’s road maintenance and reconstruction backlog had ballooned to $8.4 billion while it received only 20% of the annual funding needed to maintain the existing road system to current environmental and safety standards.

The agency adopted an 18-month moratorium in February 1999, pending completion of an overall road management policy. Later that year, President Clinton instructed the agency to undertake a rulemaking process to provide long-term administrative protection for roadless areas. Over the next 14 months, the Forest Service conducted an extensive public involvement process that produced 1.7 million comments, with the majority favoring a strong national policy protecting roadless areas.

“The public has rightfully questioned the logic of building new roads when the Forest Service is inadequately funded to maintain its existing road system,” Dombeck said in March 2000. “This proposal addresses how to maintain our existing road network in an environmentally and financially responsible way.”

Keith Hammer, executive director of the Swan View Coalition, one of the region’s most enduring forest-watchdog groups, concedes that what began as a fiscally prudent solution to an unwieldy network of forest roads has become a bedrock of the conservation movement. But even though the Roadless Rule has afforded key protections to fish and wildlife habitat and restricted logging in sensitive ecosystems, its development a quarter century ago was spurred by the need to contain costs.

“The Roadless Rule was issued to make government more efficient by not building roads in sensitive areas when we already have far more roads than we can afford to maintain,” Hammer said. “Rescinding the rule will result in government waste and environmental harm, all at taxpayer expense.”

According to Hammer, local ranger districts haven’t had the money to maintain roads in decades, while the maintenance funds they do receive are often exhausted while planning timber sales.

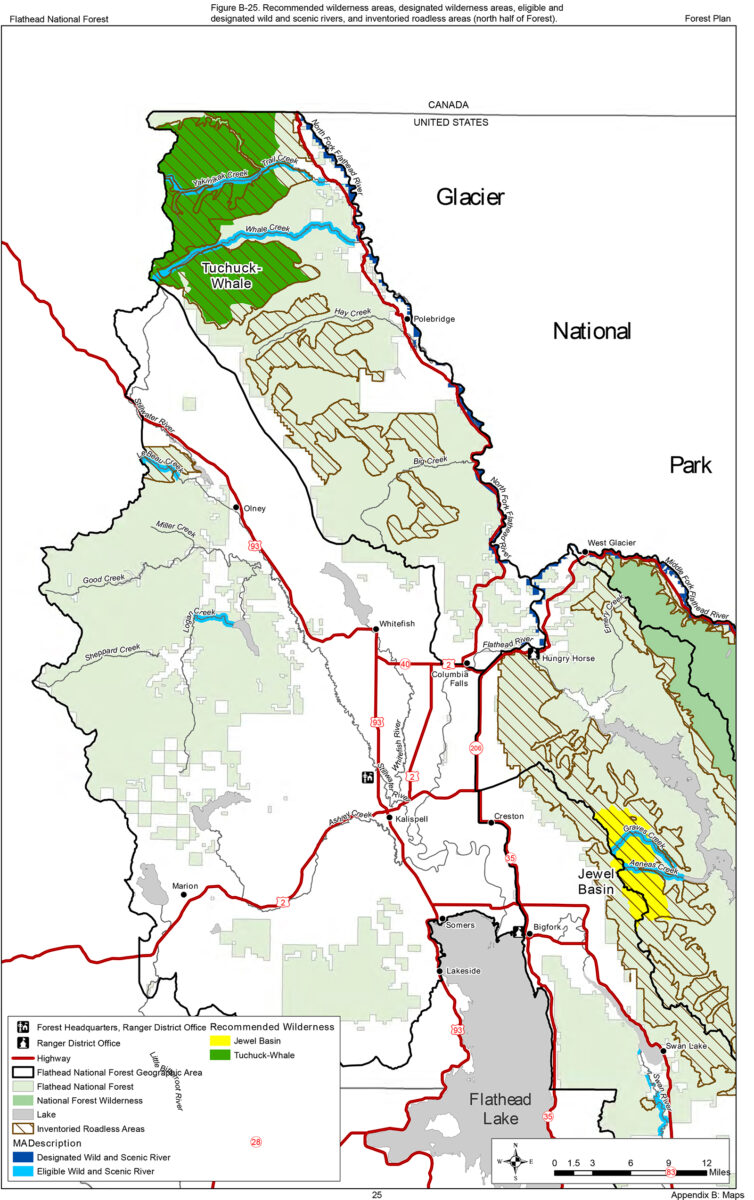

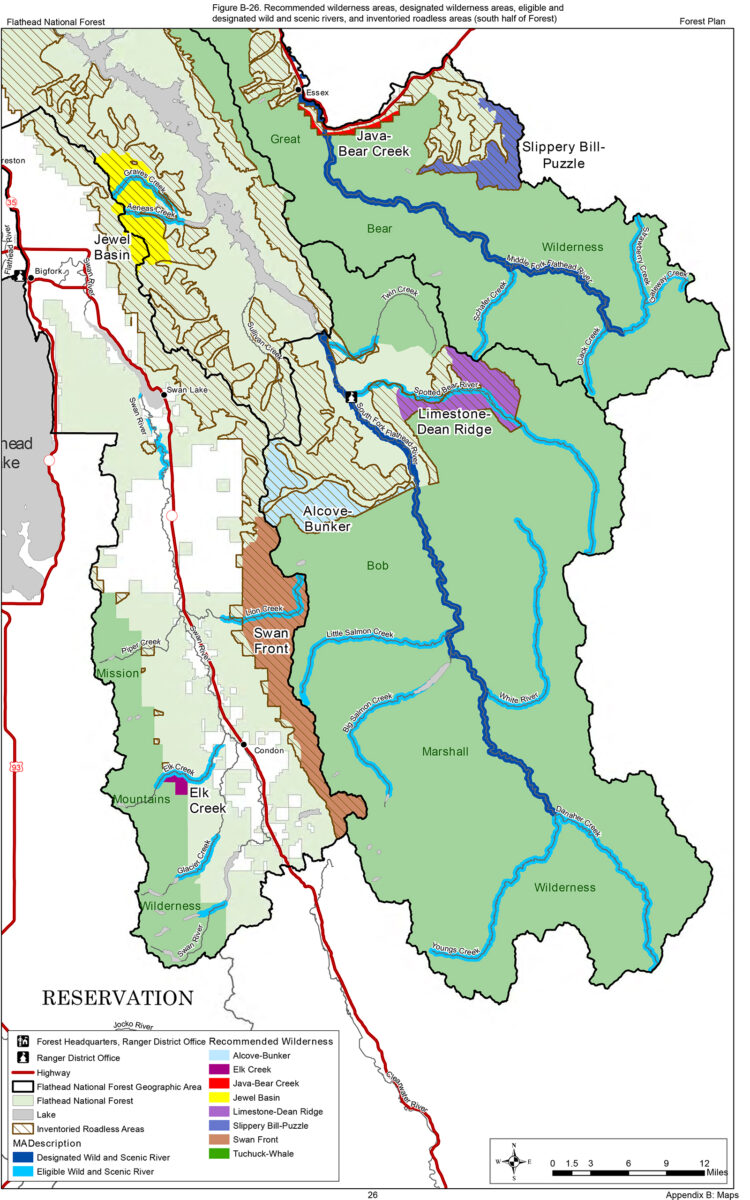

The Flathead National Forest includes an inventoried roadless area spanning 478,000 acres, mostly flanking the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area along the Swan Range, as well as west of the North Fork Flathead River in the Whitefish Range. In the Kootenai National Forest, about 639,000 roadless acres border the Cabinet Mountains Wilderness.

According to a Travel Analysis Report prepared in 2014 by the Flathead National Forest, it has 3,519 miles of National Forest System roads, but only about 1,700 of them are maintained — 27% are managed for passenger vehicles while 14% are managed for high-clearance vehicles but are still open to the public. The remaining 59% are in custodial care and are closed to public motorized use. Moreover, the total number of roads on the Flathead National Forest has been steadily decreasing since 1995.

At the time, the agency reported it “receives approximately 42% of the funds needed to maintain the road system to standard.” The report also notes that 55% of the funding the Flathead National Forest allocated for construction and maintenance of roads goes to support timber sales rather than directly to road maintenance. As recently as 2022, the U.S. Forest Service’s deferred maintenance backlog for roads and bridges was estimated at $4.4 billion.

With those figures in mind, Hammer said he doesn’t see how the agency expects to rein in the road maintenance backlog while increasing timber harvests, particularly as President Trump proposes slashing millions of dollars from its budget in addition to cutting 30% of its non-firefighting workforce.

Still, longtime timber industry officials, as well as retired forest administrators and former forest planners, said the Roadless Rule has created overlapping regulations and layers of redundant restrictions.

Paul Mckenzie, vice president and general manager of F.H. Stoltze Land & Lumber Co., said revisiting, and ultimately rescinding, the Roadless Rule could remove obstacles the agency has confronted as it seeks to fulfill its mission in other ways, while stewardship agreements between the state and federal governments can add boots to the ground and help increase timber production and fuels reduction projects.

“Just because this rule is no longer in place doesn’t mean we’re going to see death by a thousand road cuts,” McKenzie said. “Local managers will gain more flexibility. It might give them more latitude to treat fuels in some areas. But if you pull up the Flathead National Forest, the inventories roadless areas are generally not in the areas identified as a suitable timber production base. They’re in other areas that have been identified for other objectives. So removing the Roadless Rule might allow us to use forest management to achieve other objectives. Maybe that’s to access recreation, or fuels management, or habitat restoration. And maybe not having the rule gives the agency a little more flexibility to achieve those objectives.”

Chip Weber, the former Flathead National Forest supervisor who oversaw the 2019 update to the forest management plan, said his experience with the Roadless Rule has cut both ways.

“There’s a yin and a yang to it,” Weber said. “I lived with the Roadless Rule for a good chunk of my career, and it’s always generated a lot of intense feelings from people on both sides of the issue. The preservation and environmental community is pretty wedded to it, and repealing it is certain to meet a lot of litigation. But we’ve always been having discussions about timber management and what it does or doesn’t do for the ecological health of a forest, and when the Roadless Rule was enacted it resolved a lot of that conflict because it provided the agency with clear direction. Before that, there were all-out wars over roadless areas.”

The Roadless Rule was informed by a pair of roadless area review and evaluation processes, known as RARE 1 and RARE 2, which were designed to identify and evaluate roadless areas within national forests for potential inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System. provided clear direction for forest managers.

One example Weber recalled in which the Roadless Rule hampered his ability to move forward with a project to improve the ecological health of a forest involved a whitebark pine restoration effort. A significant portion of whitebark pine habitat in Montana exists within inventories roadless areas, which restrict timber harvesting to maintain their undeveloped character. Because the Roadless Rule seeks to balance wilderness values and restoration, it allows for some prescribed fire and targeted thinning, which is crucial for restoring these systems.

But Weber said the Roadless Rule still adds a layer of complexity to those forest health initiatives.

“From an environmental analysis perspective, it was much more challenging because it was roadless made it much more difficult to conduct any kind of targeted work to preserve a species at risk, so from an environmental management perspective it would have helped [to have rescinded the Roadless Rule],” Weber said.

Rob Carlin, who retired as the Flathead National Forest’s lead planner, said many of the region’s inventoried roadless areas were cataloged as roadless for a reason — they’re not necessarily suitable for timber production.

“There are some false impressions that there’s a lot of really viable productive timber in these roadless areas. In some areas there are, but in other areas it would be very difficult and overly expensive to build a road system,” Carlin said. “We’re talking about steep, rocky terrain, at high elevations with short growing seasons. It might get reclassified as suitable for timber management, but those scales might only tip in favor of fuels treatment, which is a different type of management objective than a commercial timber harvest.”

Carlin said it’s also possible to conduct fuels treatment and prescribed burning without building roads, and therefore without compromising the roadless character of an area.

“The steep-and-deep stuff will remain off limits, but the added flexibility for local managers could be beneficial for some objectives,” he said. “As far as strictly timber harvests, there are areas that haven’t been managed yet not because they’re roadless, but because we just haven’t got there yet. There are lands unsuitable for timber production where timber harvest is allowed, and there are lands unsuitable for timber production where timber harvest is not allowed.”

But Roadless Rule advocates said architects of the rule’s rescission are disingenuous in their portrayal of it as a wildfire-mitigation maneuver, and decried the move as another step toward defanging bedrock environmental protections.

The Wilderness Society, which studied the relationship between roads and wildfire occurrences, has published research concluding that roads can increase the risk of wildfire ignitions. According to the organization’s research, which analyzed wildfire data between 1992 and 2024, wildfire ignitions are more likely near roads compared to areas without them. Indeed, wildfires are nearly four times to start in forest areas with roads than in roadless areas.

Hammer said inventoried roadless areas are valuable for absorbing greenhouse gases, providing wildlife habitat and protecting clean drinking water. He also notes that the Roadless Rule includes provisions allowing fire prevention work within these areas when necessary.

Because the Roadless Rule was an administrative initiative, not a congressional measure, its repeal will require a formal rulemaking process to ensure the agency action complies with the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, including the preparation of an environmental impact statement. In that regard, rescinding the rule could create additional headaches for the beleaguered federal agency, while its removal won’t immediately clear new boulevards toward more effective timber management.

“If the Trump administration finalizes this idea of deleting the Roadless Rule, we’ll see them in court,” Drew Caputo of Earthjustice said this week.

For stakeholders in the timber products industry, a drawn-out legal battle won’t help their bottom line, nor will it promote forest health and wildfire mitigation, McKenzie, of Stoltze, said.

“We’re trying to find ways to get work done in the forest, not find ways to not get work done in the forest,” McKenzie said.

Sarah Lundstrum, Glacier program manager of the National Parks Conservation Association, raised practical concerns about whether rescinding the Roadless Rule will have any measurable effect on combatting the wildfire crisis. To Lundstrum, it makes more sense to focus resources to mitigate wildfire risks on the wildand urban interface, where wildfire is most likely to threaten human health and safety, rather than in roadless areas, which are located in more remote terrain. She also worried that the rescission will compound other moves by the Trump administration to pare back layers of environmental analysis and public review at a time when the agency is still coming to grips with cuts that are both past and pending.

“I think that rescission is going to put high quality hunting lands and areas valued for their quiet recreation opportunities and remoteness at risk. The lands we are talking about on the Flathead are hard to get to, hard to log and hard to build roads in,” Lundstrum said. “Given the reality of U.S. Forest Service budgets and staffing, including the road maintenance backlog they have, building more roads is irresponsible and unrealistic. The Forest Service would do better to focus their efforts on fuel mitigation in places close to communities.”

Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz during testimony last week to the Senate Committee on Natural Resources said the process to rescind the Roadless Rule would begin in October and would include an opportunity for public comment.