The Wild Life of Danny On

While locals are familiar with Danny On as the namesake of a popular hiking trail at Whitefish Mountain Resort, a smaller segment of the Flathead Valley knows about his World War II heroics, or his career as a smokejumper, forester and nature photographer

By Chad Sokol

The D-Day invasion began in the dark early hours of June 6, 1944, when more than 13,000 U.S. Army paratroopers jumped into Normandy from the holds of C-47 transport planes that had departed from England.

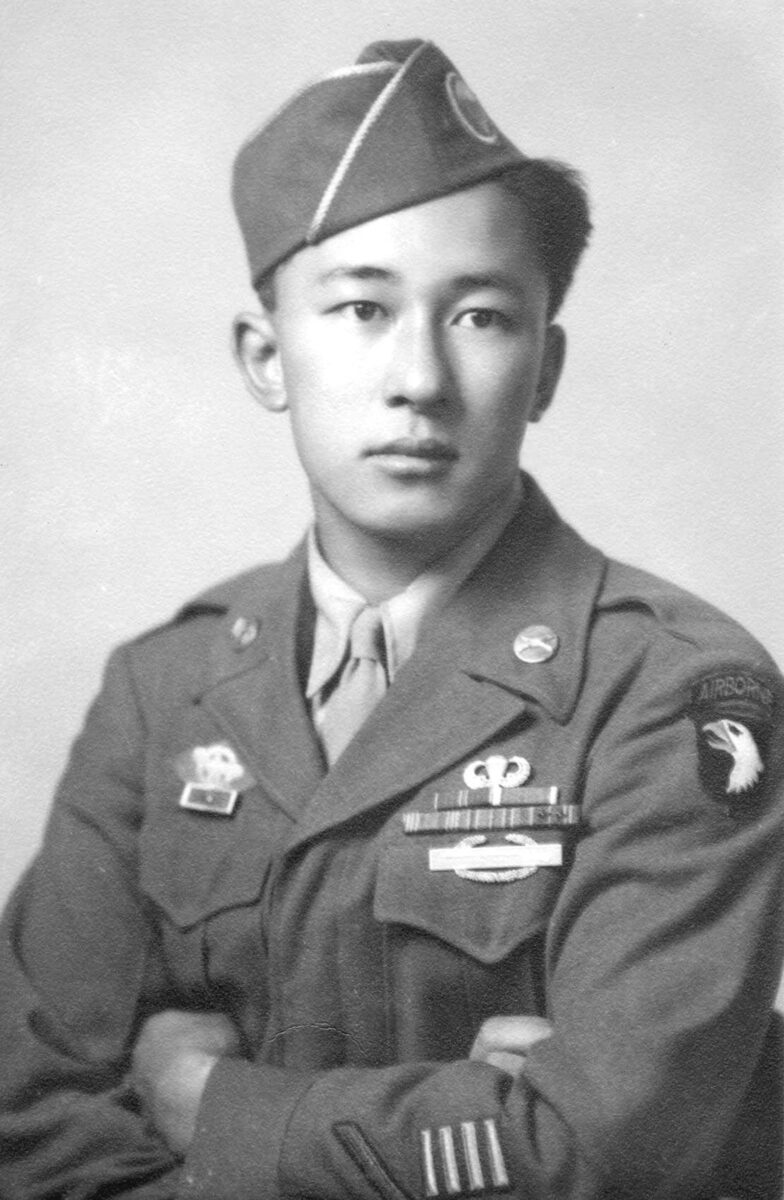

Pfc. Danny On, then 20 years old, was among them. A talented parachutist with the 101st Airborne Division, he had trained for two years before the invasion, his first experience in combat.

“I thought I was going to get killed on D-Day,” he would later write to his sister. “We were moving toward the beachhead when we were warned not to go down the road because there were two German machine guns. I was second from the front and the officer said ‘Go’ and it just happened that Jerry had gone.”

On fought not only in France but also in the Netherlands and Belgium, where he was wounded in the Battle of the Bulge. Throughout the war, he wrote letters to friends and relatives back home in Red Bluff, California, where the local newspaper dutifully published excerpts and celebrated On as a hometown hero.

Eight decades later, many know Danny On as the namesake of a popular hiking trail at Whitefish Mountain Resort, which beckons thousands of visitors each year with panoramic views of the Flathead Valley and the dramatic peaks of Glacier National Park.

On himself was just as impressive.

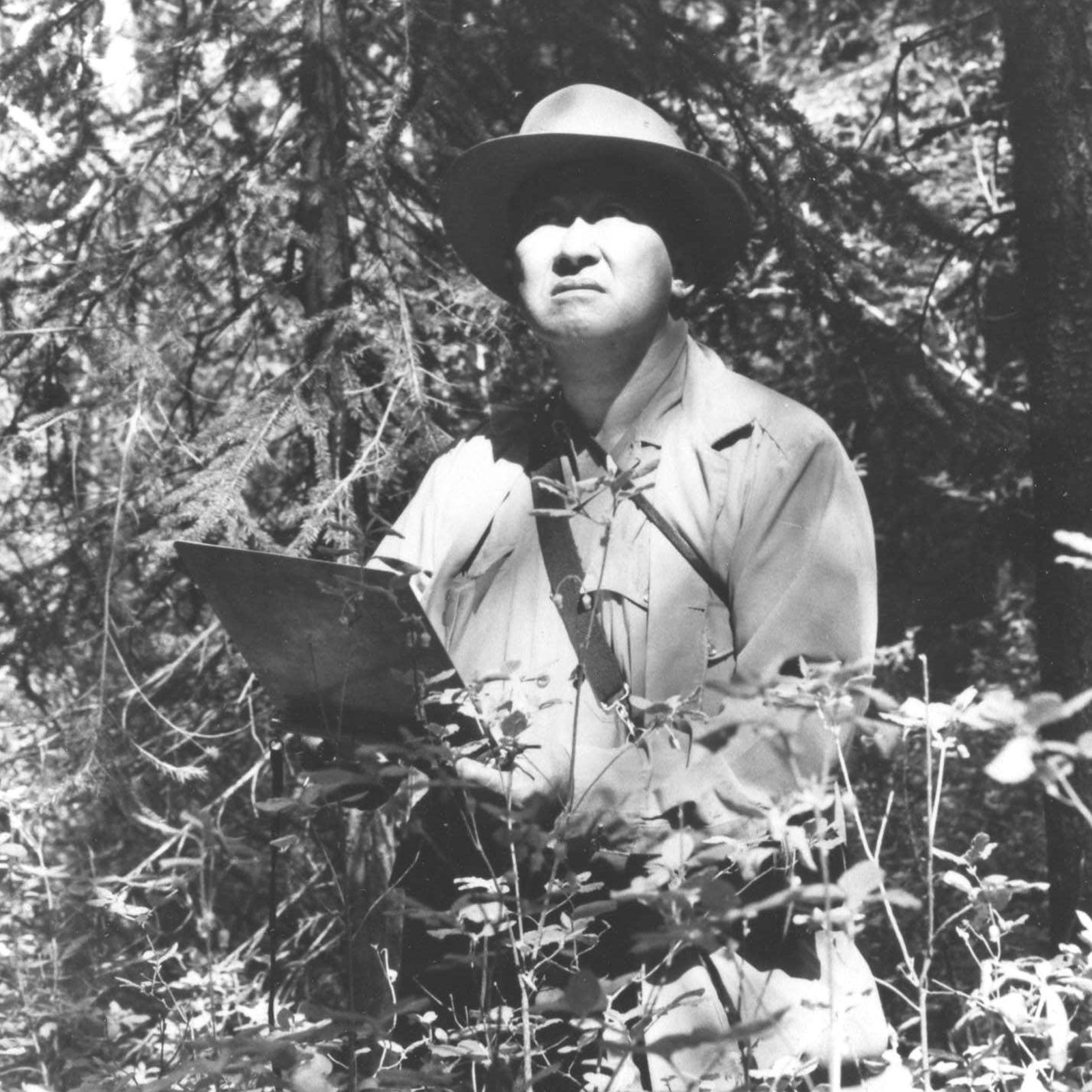

After World War II — and after a vaunted career as a smokejumper for the U.S. Forest Service — On was a forester and renowned nature photographer who lived in Whitefish in the 1970s. The hiking trail was built and dedicated after On died in a skiing accident on Big Mountain in 1979. He was 54.

On was known as a man of few words, preferring to speak through his vivid photos of Rocky Mountain wildlife. He never married or had children, but he was a beloved figure seemingly everywhere he lived, and his activities rarely went unnoticed.

This story is based on hundreds of newspaper articles published about On during his lifetime, many of which are preserved in online archives, as well as public records and other accounts.

“Among us are a few men and women who become legends even as they are friends and neighbors,” Mel Ruder, the late Pulitzer Prize-winning editor of the Hungry Horse News, wrote in the foreword to a book of On’s photos. “Danny was such a man.”

On was born in Red Bluff, Calif., on May 11, 1924. At the time, the town along the Sacramento River was home to fewer than 3,500 people.

Danny’s parents, grandfather and older brother had emigrated from China’s Guangdong province. According to the Tehama County Genealogical & Historical Society, they were one of five Chinese families to settle in Red Bluff around the turn of the century. Danny was one of seven siblings and the first born in the United States.

The Ons owned and operated a restaurant called the American Cafe, which advertised Chinese and American meals as well as homemade chicken tamales — a recipe Danny’s mother had acquired from a patron, according to the historical society. The family lived in the back of the restaurant after their home burned down due to faulty wiring in 1929.

Danny began appearing in the pages of the Red Bluff Daily News when he was a child. Several themes were apparent from the start: He craved adventure. He loved the outdoors. And he reveled in risk-taking.

In the spring of 1938, when he was 13, Danny and an older boy paddled a canoe into a raging section of the Sacramento River, brushing aside words of caution from a local shopkeeper. The canoe capsized and the other boy drowned in the turbulent water, while Danny clung to some branches, swam to the riverbank and alerted authorities to start a search, the Daily News reported at the time. The other boy’s body was discovered nearly two months later.

Throughout his teens, Danny was deeply involved in the Boy Scouts, hiking the mountains around his home and collecting badges for skills like cooking, carpentry and first aid. At 16, he became the first in Red Bluff to earn the highest rank of Eagle Scout.

Danny was also a defensive lineman on the football team at Red Bluff Union High School, “whose rugged, low-charging type of play made the ball carriers look bad time after time,” according to one game recap in the Daily News.

Story after story celebrated his youthful achievements.

Then, during Danny’s senior year, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States went to war. His older brother Louis enlisted in the Army Air Corps, while a younger brother, John, joined the Merchant Marines.

Danny reported for the draft on his 18th birthday and entered the Army in May 1942.

That summer, while training at California’s Camp Roberts, On wrote to a friend that he’d volunteered to join the rigorous training program to become a paratrooper. He later insisted, with a touch of bravado, that jumping out of planes wasn’t a dangerous line of work.

“But it’s mighty hard work,” he told the Daily News while home on a furlough. “And a fellow has to be in first-class physical condition to go through with it.”

On completed Jump School at Fort Benning in Georgia and was assigned to G Company, 3rd Battalion, of the 101st Airborne’s 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment. The division’s famous “Screaming Eagles” patch was stitched on the shoulder of his uniform, and in September 1943 he departed for Europe with the rest of the 502nd.

“I like it here very much,” he wrote upon arriving in England. “After being in the warm holds of a ship for a month, this English climate feels wonderful. It makes me think of our mountains at home.”

On and fellow soldiers spent the next seven months in the English village of Chilton Foliat, where they continued a grueling training regimen that involved long hikes and close-combat exercises. On served as an instructor as the regiment rehearsed parachute drops, earning commendation letters from his company and battalion commanders.

In one letter from Chilton Foliat, On described “the roar of many planes going over, en route to bomb the enemy” and expressed gratitude to the Red Cross for the meals and treats the group provided to the troops.

“Time is going by pretty fast and I am getting along fine,” he wrote. “I go for several days at a time and don’t think about combat. It seems so remote.”

Shortly after jumping into Normandy on D-Day, the 101st Airborne was ordered to capture the inland farming village of Carentan. The town was strategically important because it would enable American troops to form a continuous defensive line between the Utah and Omaha landing beaches, thus controlling the Cotentin Peninsula.

On’s battalion was tasked with approaching Carentan via a flat, exposed causeway. Along it, the Germans had flooded crossroads, destroyed a bridge and erected a massive anti-tank barrier known as a Belgian gate, which soldiers could squeeze through only one at a time.

The paratroopers advanced slowly, at times crawling along the banks of the causeway, under barrages of German sniper, machine gun, artillery and mortar fire. They suffered so many casualties that they dubbed the road Purple Heart Lane.

By the morning of June 11, the battalion’s commander, Lt. Col. Robert Cole, was desperate to capture a farmstead on the outskirts of Carentan. So he ordered his remaining men — including On’s company — to charge German gunners’ positions with fixed bayonets. A long, bloody and tragic day of close-up fighting ensued before American artillery flattened the last German counterattack.

“The water along the causeway was running red from the blood of so many Americans,” military historian John McManus wrote in an account of the battle. “From the 700 young men at Cole’s command, just 132 were still standing.”

After their hard-fought victory, On and the rest of the 502nd were relieved and the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment continued the push into Carentan. The bayonet charge would come to be known as “Cole’s charge” and earn the battalion commander a Medal of Honor.

In the aftermath, On spent time “souvenir collecting” in the battlefields of Normandy. He shipped home two boxes full of military artifacts, including a green nylon parachute, which his parents proudly displayed at their restaurant.

“In the window of the cafe there are German knives, helmets, fur-lined knapsacks and postcards picturing everything from young Nazi fliers to the once-peaceful Normandy coast and a statue of Napoleon at Cherbourg,” the Daily News reported that summer. “Outside, there’s a formidable white poster with a grinning blue skull, under which the warning ‘Minen!’ (mines) is printed in red.”

In September 1944, On went to the Netherlands as part of Operation Market Garden, an attempt by tens of thousands of American and British soldiers to cross the Rhine River into German territory. He saw more intense fighting around the Dutch town of Best, where his battalion commander, Cole, was killed by a German sniper before he could receive his Medal of Honor.

That December, On joined a convoy into the Belgian town of Bastogne. There, despite being surrounded and vastly outnumbered, American troops managed to slow the advance of German forces across the Ardennes region — a pivotal success in the broader Battle of the Bulge.

On Dec. 21, a day after the siege began, a piece of artillery shrapnel tore through On’s right shoulder.

“We had set up positions around the town,” he wrote. “The Germans started dropping 88 mm shells on the town, and one landed near me, spreading shrapnel in every direction. A medical soldier applied first aid and later took me to an aid station from where I was brought by ambulance and plane to England.”

For his service, On was awarded two Purple Hearts and a Bronze Star.

A final gesture of recognition came in 2018, nearly four decades after On’s death, when lawmakers passed a bill to collectively award a Congressional Gold Medal to the roughly 20,000 Chinese Americans who served in World War II. The bill recognized that people of Chinese ancestry faced rampant discrimination in the United States before, during and after the war. On’s name is on the official list of veterans recognized by the Gold Medal.

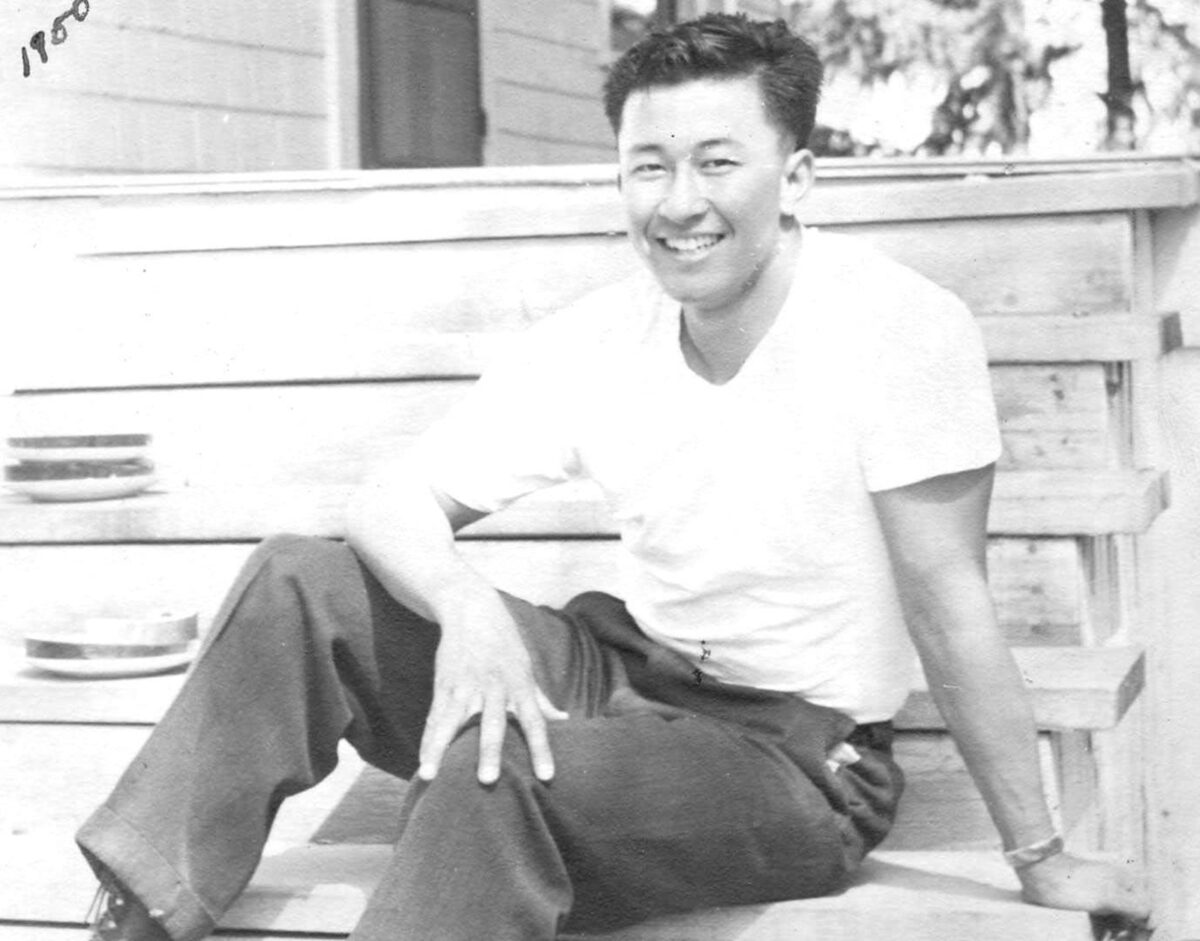

After the war in 1945, On returned to California and enrolled at Chico State College. The following year he transferred to the University of Montana in Missoula (then called Montana State University) where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1950 and a master’s in 1952, both in forestry.

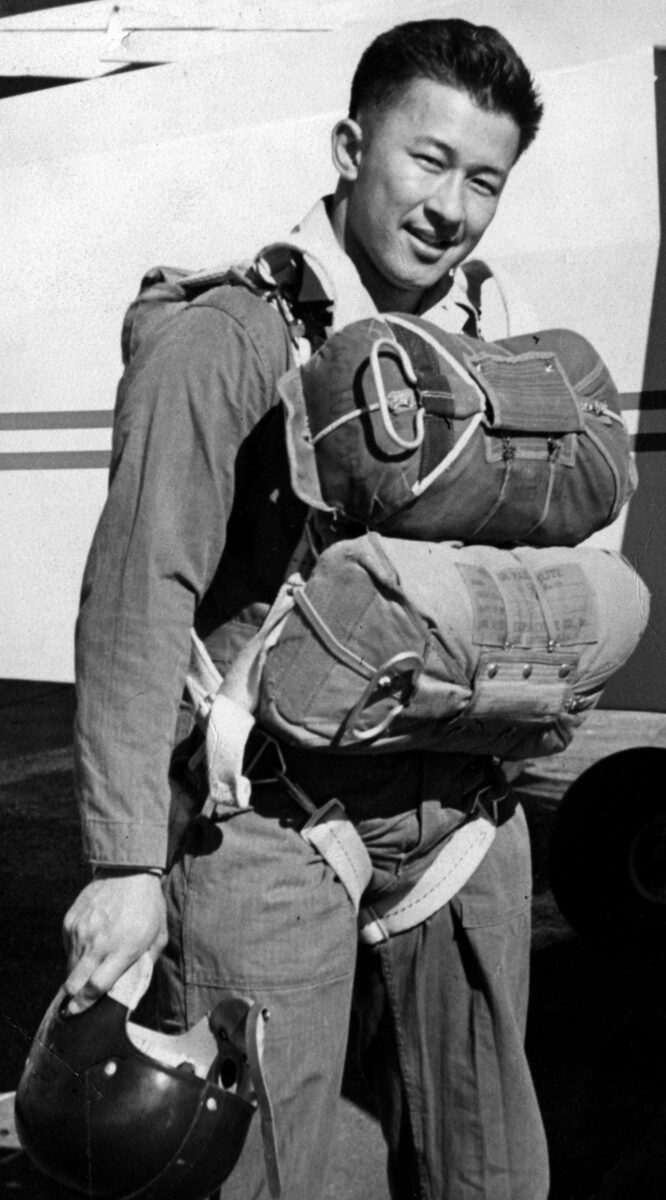

While in college, On spent his summers at the Siskiyou and Lolo national forests working as a smokejumper, an elite firefighter who parachutes into backcountry terrain to battle blazes on the ground. He was one of two dozen new smokejumpers, most of them WW II veterans, who began training at Cave Junction, Ore., in 1946.

He was also the first Asian American to serve as a smokejumper, according to the Forest Service’s Asian Pacific American Employees Association.

On had a reputation as a singularly daring parachutist, known for performing extended free falls as well as breakaway jumps, in which a skydiver deploys one canopy, then abandons it to fall a bit more, then deploys a second canopy.

“He was a legend among the ex-paratroopers, skydivers and smokejumpers during the late ’40s and early ’50s,” George Ostrom, the late Flathead Valley newsman and radio announcer, wrote in a 2008 remembrance in the Hungry Horse News.

Ostrom, who also served in the 101st Airborne before training as a smokejumper at Cave Junction, said On “was doing freefall parachuting that scared those of us who claimed to be afraid of nothing.”

On and another smokejumper, George Harpole, together performed at least two exhibition jumps in 1951, parachuting into rodeo grounds in Missoula and Spokane before cheering audiences. Harpole would later recall, in a letter to Smokejumper Magazine, that he and On agreed to the Spokane exhibition for $200 each, “which was a lot in 1951 dollars.”

A university student interviewed On for the Montana Kaimin ahead of the Missoula rodeo. The story noted On already had 55 jumps under his belt, “and his only injury has been a sprained ankle.”

Once, the story noted, “On jumped in a 27 mph wind, drifted close to a mile, hit a billboard splintering a 2×6 plank and landed on a sidewalk unhurt.”

After he received his graduate degree in 1952, friends and colleagues nudged On to quit smokejumping and apply for a position in timber management.

“Our feeling at that time was that Danny On was going to kill himself before he hit 30,” Ostrom wrote. “Some of us were worried that maybe Dan had decided he was indestructible.”

On relented, stowed away his parachute and worked for brief stints in the Siskiyou and Deschutes national forests. By late 1956, he was assigned to a Kootenai National Forest ranger station in Fortine, just south of Eureka, where he taught hunter safety courses and practiced archery, shaping his own bows out of yew and hickory.

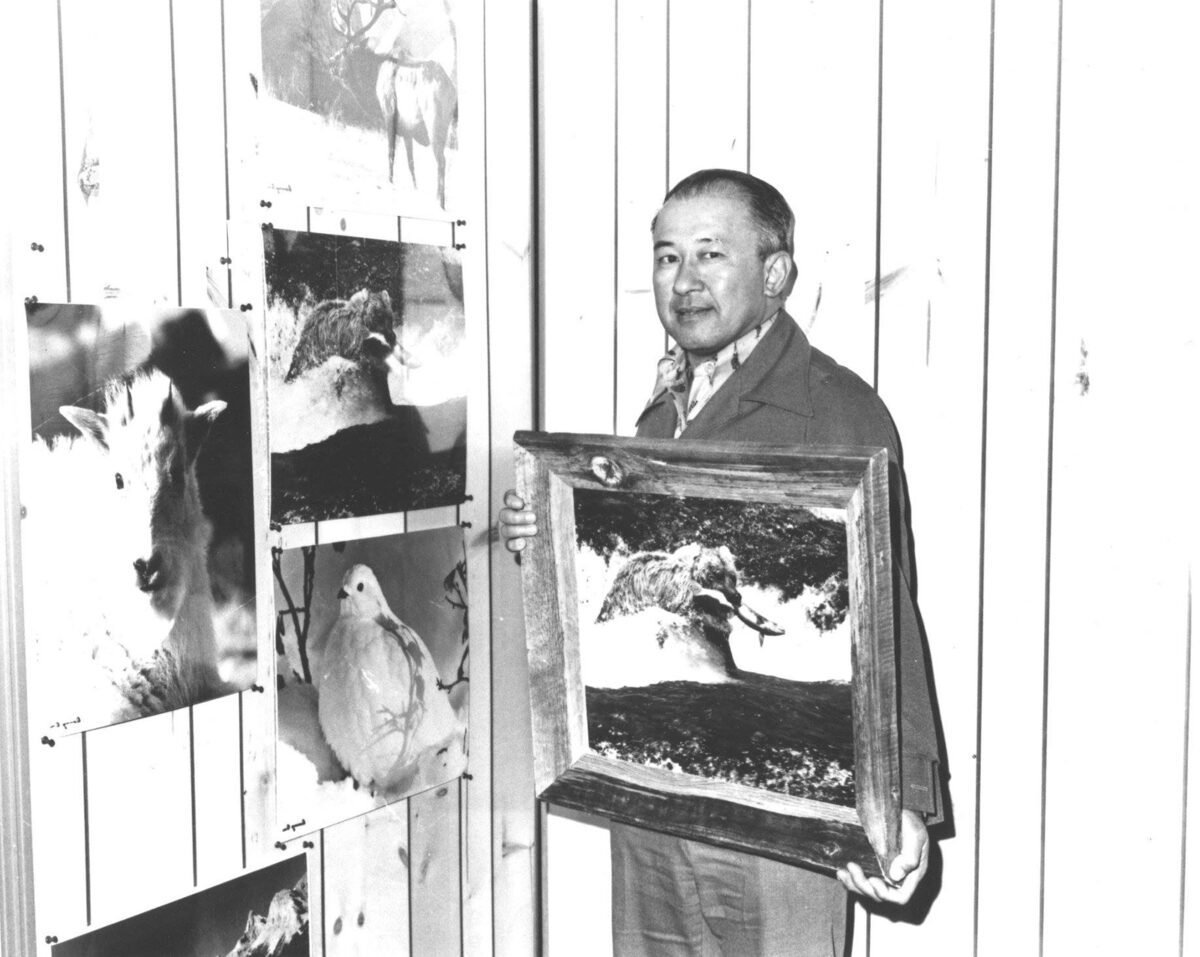

He took every opportunity to hike and ski across British Columbia, the Grand Tetons, Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness, all the while honing his photography skills at a time when professional color photos of the region’s wildest corners were a rare delight. And because acquaintances in Libby and Eureka knew him as the man with the camera, he was often asked to moonlight as a wedding photographer.

After several promotions within the Forest Service, On returned to Missoula in 1963 to start a new job as a silviculturist, or applied forest ecologist.

His photography work continued to garner acclaim, and in 1971, the Missoulian published a two-page Sunday spread featuring a selection of his photos: A fox creeping through snow; an antelope standing in tall grass with a dramatic peak rising up in the background; an osprey in flight.

“It’s possible that Danny On has become an outstanding wildlife photographer because of his straightforward, guileless approach to photography and to life,” the story said. “He has walked and looked for months at a time, shot miles of film and developed reams of photographs. Through it all he has maintained an aw-shucks-it-was-nothing manner that belies his dedication. As his photos show, this modest photographer has honed his talents to consummate artistry.”

In 1973, On was transferred to Whitefish to continue working as a silviculturist for the Flathead National Forest. He moved into an apartment on Big Mountain, where he skied every winter, and joined the board of the Glacier National History Association.

By the late ’70s, he was nearly finished working on a book with Richard Shaw, a botany professor at Utah State University. Titled “Plants of Waterton-Glacier National Parks and the Northern Rockies,” it would be an encyclopedic guide to the region’s flora featuring hundreds of On’s photos of native trees and wildflowers.

He would not live to see it published.

Sunday, Jan. 21, 1979, was a windy, cloudy, snowy day on Big Mountain.

According to Ostrom, On had recently returned from a heli-skiing trip in the Bugaboos, a mountain range in British Columbia, and had spent all weekend skiing the Big, hunting for untracked powder in the trees.

But at some point that Sunday afternoon, On enjoyed his last turns. He either was skiing alone or became separated from his partner — reports from the time are vague — when he crashed head first into a tree well, became trapped in the snow and suffocated.

The next morning, a mountain employee noticed On’s vehicle was still in the parking lot and feared the worst. A search-and-rescue effort ensued, and hours later a ski patroller spotted one of On’s boots poking up through the snow.

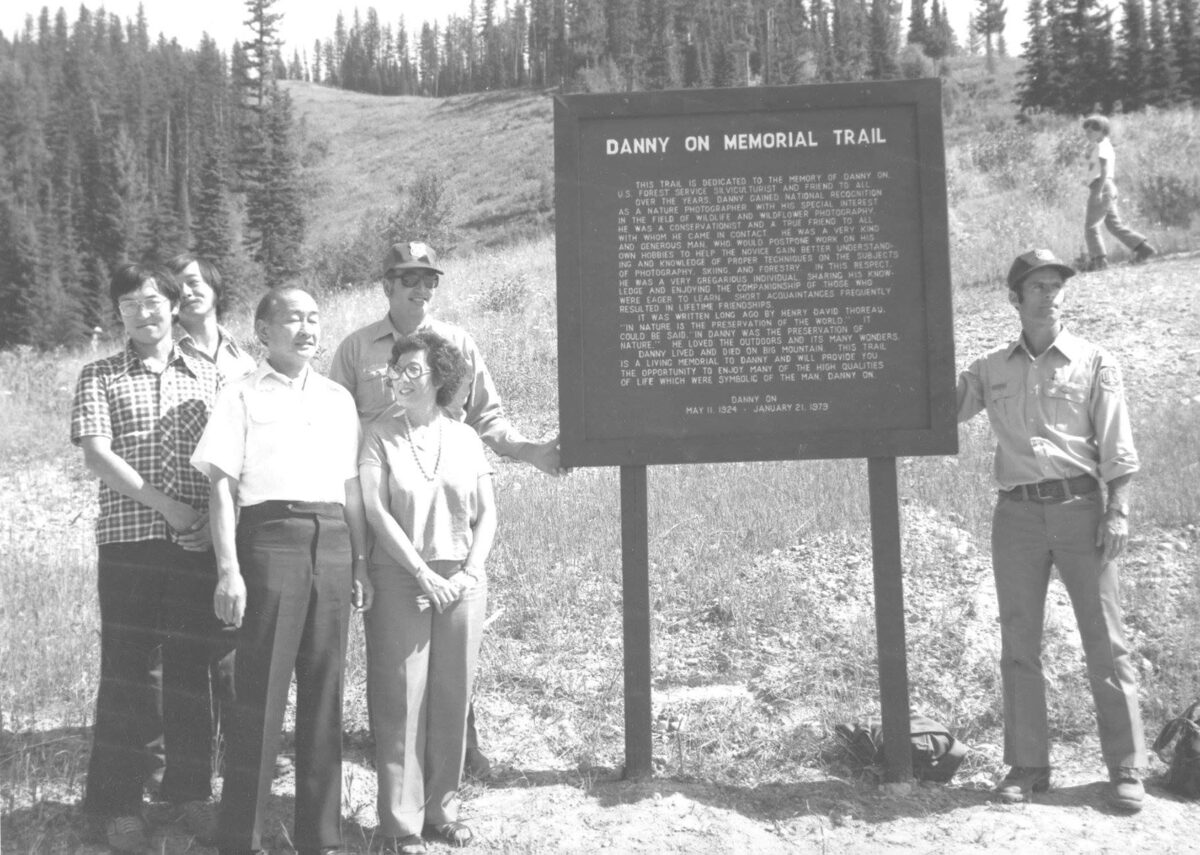

While On was buried in Red Bluff, more than 300 friends and colleagues attended a memorial service at the Outlaw Inn in Kalispell, and someone floated the idea to build a hiking trail in his memory. His Forest Service colleagues formed a committee and got to work mapping the route “with loving regard for the things that were precious to On,” the Whitefish Pilot reported at the time.

The trail would meander through evergreen woods and wildflower-studded meadows before reaching the 6,800-foot summit of Big Mountain. Along the way, hikers might witness beargrass and Indian paintbrush in bloom, or snack on huckleberries, or spot a deer, or maybe even a bear and its cubs, bounding along a nearby slope.

In the summer of 1980, the Pilot reported, “a crew of Young Adult Conservation Corps workers began to hack the trail out of the mountainside with chainsaws, Pulaskis and shovels.”

The Danny On Memorial Trail was dedicated in August 1981. Several of On’s relatives traveled from California to attend the ceremony, and a sign describing On’s legacy was installed at the trailhead.

“The wildflowers — yellow, red, blue, white and gold — are blooming profusely along the Danny On Trail,” a Pilot story said at the time. “Danny would have loved it.”

Books featuring Danny On’s photography

• Plants of Waterton-Glacier National Parks and the Northern Rockies, by Richard Shaw and Danny On (1979)

• Along the Trail: A Photographic Essay of Glacier National Park and the Northern Rocky Mountains, by David Sumner (1979)

• Going-to-the-Sun: The Story of the Highway Across Glacier National Park, by Rose Houk and Pat O’Hara (1984)

Hiking the Danny On Memorial Trail

The trail begins in the village area at Whitefish Mountain Resort, near the bottom of Chair 2, and climbs 3.8 miles to the summit of Big Mountain. Adding the popular Flower Point loop extends the hike to 5.4 miles. It is considered a challenging trail as it ascends more than 2,000 vertical feet. For those who want to hike only one way, the resort offers chairlift and gondola rides to and from the summit. More information can be found at skiwhitefish.com.

Chad Sokol is a former journalist who currently works as the public relations manager at Whitefish Mountain Resort.

Correction: An earlier version of this story, as well as the version that appeared in print, misidentified the location of Danny On’s memorial service. It was in Kalispell, not Whitefish. We regret the error.