From ‘Nebraska’ to Whitefish: The Man Behind Springsteen’s Sound

As the Springsteen biopic "Deliver Me from Nowhere" hits screens, Whitefish sound engineer Toby Scott looks back on decades in the studio with the Boss

By Katie Bartlett

Before “Nebraska” became a career defining acoustic turn for Bruce Springsteen, it lived on a cassette tape that he carried in the front pocket of his jacket. Springsteen kept it there for months without even a case on it before finally pulling it out to share with Whitefish resident Toby Scott, his sound engineer.

It was 1981, more than half a decade after Springsteen’s third album, “Born to Run,” had launched him to fame. He was finishing up the tour for “The River,” riding the high of his first Top 10 hit, “Hungry Heart.”

But it was also a period marked by what he later described as his “first real major depression,” a mood reflected in “Nebraska’s” haunting lyrics and raw, lo-fi sound.

“I just hit some sort of personal wall that I didn’t even know was there,” Springsteen said on CBS in 2023.

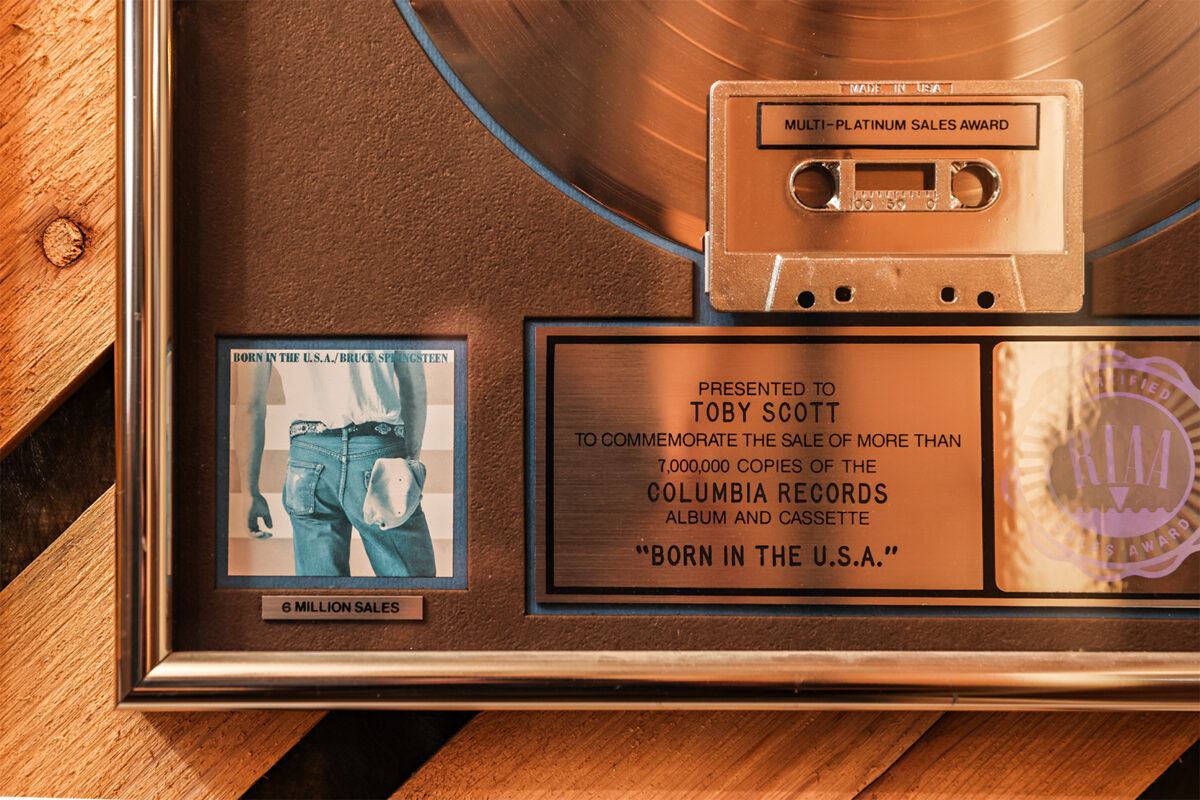

Scott had been working with Springsteen since 1978, engineering “Darkness on the Edge of Town” and “The River.” They were holed up in Manhattan’s Power Station for three weeks, tracking nearly 10 songs in quick succession and starting to mix what would become “Born in the U.S.A.”

Scott was used to working fast, but Springsteen wanted to take a step back from “Born in the U.S.A.” Instead, he decided to revisit the home demos he’d first recorded on the cassette tape.

First, he tried playing the songs in the studio. His band added light percussion and a few synth pads. To Springsteen, it didn’t sound quite right.

He had recorded the tape in a rented house in his native New Jersey, in a makeshift studio set up by his guitar tech, Mike Batlan. Batlan lacked any training in sound engineering, and the room’s orange shag carpet sucked up sound, making for dead acoustics. And yet, there was something special about the emerging sound.

Now, attempting to recreate the magic of that moment with a professional sound setup, Springsteen struggled.

“It just wasn’t working — he couldn’t get that same feeling and emotion he’d had on the demos he did at home,” Scott recalled. “So, he pulled the cassette tape out of his pocket, tossed it to me, and said, ‘Tobe, what’s the chance that we can master off of this?’”

Sound engineers are taught to chase the perfect sound with the best equipment. Springsteen’s request broke every rule Scott knew. Still, he respected Springsteen’s vision and agreed to try.

The DIY recording was riddled with problems — distortion, sound warping, uneven levels — that made it nearly impossible for Scott and the mastering engineers to transfer the tape onto a disc. The mastering needles kept jumping from the grooves, thrown off by the tape’s imperfections.

Scott and co-producer Chuck Plotkin then took the cassette to two studios in New York. Both failed to subdue the stylus. They tried another in Los Angeles with the same result.

Just when they were ready to give up, they brought it to Atlantic Records in New York, where engineers Dennis King and Bob Ludwig finally found a solution. Using a partly manual cutting system, they adjusted the lacquer just enough to keep the needle in the groove, preserving the raw, home-recorded sound that defines the album.

“Nebraska” is celebrated as an intimate departure from Springsteen’s previous arena-rock anthems — it is the work that Springsteen himself has said best represents who he is. More than 40 years after its release, the new “Deliver Me from Nowhere” biopic revisiting its creation has brought fresh attention to the artist’s most minimalist album — and the people who created it.

Among them is Toby Scott, who commuted from coast to coast at the call of “the Boss” for decades while living in the Flathead Valley. He still calls Whitefish home, running Cabin 6 Recording Studio and serving as the town’s Community Development Board Vice President. Scott joined the Flathead Beacon for a conversation to reflect on his years in the studio with Springsteen and the life he’s built in Montana.

“I wasn’t consulted about the movie at all. I had people telling me I was in it long before I found out,” Scott said. “So I did some digging online and saw that while I’m listed on the second page of credits, it was true.”

Scott hadn’t seen the film at the time of the interview — he was in Long Beach, Calif. for the Audio Engineering Society’s annual show when it premiered last week. Still, he looks forward to watching it and is curious to see how it tells the story he witnessed firsthand.

The movie is based on Warren Zanes’ book “Deliver Me from Nowhere: The Making of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska.” While he respects the research Zanes put into the book, Scott considers it, and the film by association, a “work of fiction.”

Some of those fictional aspects are already visible in the trailer, he says. It shows Jeremy Allen White as Springsteen and the band working closely together in a circle while attempting to record “Nebraska’s” title track in the studio.

In reality, Scott recalls the process as far more separated. Springsteen was in an isolation booth by himself, with the guitar player in a room next door. The drums and bass players were in another room, and the saxophone player — who was on tambourine — was in the hallway.

“The basics of the story they told are fairly accurate, but I don’t think it should be called a documentary or nonfiction in the sense that it depicts everything exactly as it happened,” Scott said. “I’ll be very curious to see if that pivotal moment when Bruce tossed me the [Nebraska] cassette tape will be in there.”

Long before “Nebraska” or Springsteen, Scott’s path in music was already taking shape as a child growing up in Santa Barbara, Calif. Much like Springsteen, he was hooked by seeing Elvis Presley play on television. He picked up the guitar and joined a high school band — only to be kicked out for refusing to play it straight.

Undeterred, he shifted to managing local bands, taking them from Santa Barbara to Hollywood for auditions. No contracts came of it, but a visit to the renowned Capitol Studio B — where legends from Frank Sinatra to Bob Dylan to Paul McCartney had recorded — left a lasting impression.

“I saw them overdubbing and thought, ‘This is neat — you can layer instruments and make them work together,’” Scott recalled. “I bought a recorder and was immediately into it.”

He had a brief stint in England, where breaking into audio engineering was easier. All five of the record companies he approached agreed to listen to his demo tape, and all five gave the same response: “You’re not what we’re looking for.”

He returned to Santa Barbara and took a recording course, which he remembers as “so primitive that now it wouldn’t even be considered a course.” But he was able to use the course and skills he taught himself in his home studio to construct a convincing resume. He went door-to-door to studios he’d seen listed on the backs of records.

By the third studio, Clover Recorders in Los Angeles, he found success. He auditioned on the spot and got the job.

“They needed someone right away,” he recalled. “So I told them I was ready and took over that same night.”

In 1978, a producer working on “Darkness on the Edge of Town” brought Springsteen to the studio to finish a final mix. Scott helped out and, in the process, met his future boss for the first time.

“I knew that he was reasonably famous,” Scott said. “But as far as I was concerned, he was just another guy.”

That casual attitude quickly got him into trouble. One late night, the team was working in Clover’s studio on Santa Monica Boulevard, an area with a “seedy reputation” in 1978, when Springsteen asked Scott where he could grab a hamburger. Scott sent him walking a few blocks to the 24-hour El Rancho Market.

Springsteen, who drove himself everywhere until the mid-2000s and rarely uses a bodyguard, was happy to make the trip alone. His future manager, Jon Landau, was taken aback when Scott told him where Springsteen had gone.

“He was thinking of [Springsteen] as this guy worth millions that needs protection,” Scott said. “But I was like, ‘he’s a big boy who can take care of himself.’”

Five minutes later, Springsteen returned to the studio unharmed, his burger in hand.

Two years later, Springsteen approached Clover again about mixing “The River.” The producer sent him straight to Scott.

The pair spent roughly 18 hours in the studio together each day while working on the album. They quickly became friends, eating lunch together and meeting up at the gym to play racquetball.

Springsteen approached him again a few months later, asking him to record concerts for a live album. His guitarist Steve Van Zandt piggybacked, requesting that Scott mix one of his own records.

When Springsteen was ready to start his next album, he asked Scott to relocate to New York, which is how they ended up together in the Power Station.

While Scott initially continued as an independent engineer who sought out other work, Springsteen eventually offered him a retainer to keep him on hold. After some thought, he accepted.

“On the one hand, the work you find as an independent can be good and can be lucrative,” Scott said. “But you also see jerks who are writing bad songs. Bruce is a nice guy, a great songwriter, and he doesn’t work all the time — I knew I’d get plenty of breaks.”

Their working relationship continued for nearly four decades. Scott moved between Los Angeles and New Jersey at Springsteen’s call, setting up home studios in whichever house the artist was residing in.

It was in one of these home studios that the pair recorded Scott’s favorite Springsteen record, “Tunnel of Love,” in 1987.

For that album, Scott built a studio in the carriage house on Springsteen’s New Jersey property, just 100 yards from the main house. At the time, Springsteen was married to actress Julianne Phillips, who would call the two to dinner as they wrapped up their evening work.

The pop-rock album, distinguished by its synth-driven sound, was a true collaboration between Springsteen and Scott. Scott programmed the drum machine and handled the synthesizer — skills he’d learned when working with a self-sustaining disco producer — while Springsteen played acoustic guitar.

Scott remembers their time as a duo fondly. He laughs at the persistent idea that “Tunnel of Love” was the “predecessor” to Springsteen’s divorce, calling those claims “full of it.”

For him, the album’s signature sound is what stands out.

“It’s a very subdued album without a whole lot of noise,” he said. “I find it very sonically pleasing.”

Soon after they finished “Tunnel of Love,” Scott was getting ready to settle down. He had just bought an apartment in New York City when Springsteen moved back to Los Angeles in 1988. He had no choice but to follow. The move would ultimately lead him to Northwest Montana.

Scott had an actor friend who had moved to Whitefish and kept pressuring him to visit. He finally made the trip for Thanksgiving in 1990. By the new year, he had bought a house.

“It was a throwback to my youth, when I’d go camping with the Boy Scouts in Yosemite,” he said. “It quickly felt like home.”

Even from Whitefish, Scott remained deeply involved in Springsteen’s world. Over the years, his role evolved: he managed the archiving process of Springsteen’s audio and video catalog while helping to launch the Archive Concert Series, which made live performances available for download through the artist’s website.

Their similar ages and physical builds occasionally came in handy. While working on the album “Human Touch” in 1992, Springsteen stepped out of his house to drive to the LA studio. He was immediately swarmed by paparazzi.

“The next day he came up to me and asked, ‘Hey Tobe, how you getting to work?’” Scott said. “‘Then he said, ‘Can I trade you?’”

The following morning, Scott walked out of Springsteen’s house wearing the artist’s hat and carrying his books. By the time the crowd of photographers realized the switch, Springsteen had sped off on Scott’s motorcycle. They swapped back at a burger joint 20 blocks away and rode the rest of the way to the studio in peace.

By 2017, though, things had begun to change. Springsteen was deep into his one-man Broadway run and no longer recording at home. A professional company had taken over much of Scott’s archival work.

“His manager called me and said, ‘You’re not doing anything, so we don’t need you,’” Scott recalled. “It took me about six months to get over the shock of not working for him.”

But Scott was clear with those who asked: the end of his time with Springsteen didn’t mean retirement. It was a chance to work for himself on his own terms.

He turned his focus to Whitefish, pouring his energy into his cozy, wood-paneled Cabin 6 recording studio. These days, he records local musicians, audiobooks, and performances by the Glacier Symphony.

He’s also deeply involved in the community, serving on the town’s Community Development Board, Lakeshore Protection Board, and the Committee of the North Valley Music School. He even mentored a high school student, now a sophomore at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, who continues to pursue his passion for sound engineering.

“When I saw him over spring break, he told me he’s light-years ahead of everyone else,” he said, smiling.

He hasn’t seen Springsteen in nearly five years, but they still check in now and then. Scott calls on rare occasions when he’s back in New Jersey and sends a text every year on Springsteen’s birthday. He plans to write again after he watches the film.

Among the highlights of his long friendship with Springsteen was a night that brought the performer to the Great Northern Bar, an experience that few of those lucky enough to see will ever forget. It was an August evening in 1996, and Scott was getting married in town. He’d booked Springsteen a room at Grouse Mountain Lodge and rented him a motorcycle for the weekend.

The night before the wedding, Springsteen wanted to go out, and Scott was quick to suggest the Great Northern.

Scott and his fiancée ducked out around midnight, exhausted from their rehearsal dinner and the long day awaiting them. But Springsteen stayed, dancing near the stage.

Around 1 a.m., he hopped onstage to join the Fanatics, the house rock ‘n roll cover band, who’d noticed the Boss and set up a spare guitar just in case.

“If there’s one thing about Bruce, it’s that he’s a great bandleader,” Scott said. “A band will go from being mediocre, good rock ‘n roll, to sensational all of a sudden because of his energy and enthusiasm.”

Within minutes, the room erupted, chanting “Bruce, Bruce, Bruce.” People stood on the red barstools and wooden booths that lined the wall. Faces pressed against the windows, while others climbed on shoulders for a better view.

“I heard it was like sardines,” Scott said. “From front of the stage to back, if your hands were by your sides, that’s where they were staying.”

By 1:15 a.m., more than a thousand people had flooded the Northern — the bar was at twice its capacity. The manager told him to start wrapping up. Every single jumping person had to be cleared out by 2 a.m.

Springsteen played a final song and ordered the crowd to go home. They cleared out in five minutes.

“‘If I had known he had that kind of control over the crowd, I would’ve let him play another half an hour,’” the manager later said to Scott.

More than 25 years later, Whitefish still remembers the night Scott brought Springsteen to town. Photos of the artist clutching a guitar hang alongside relics of the Great Northern’s past — memorabilia from its railway roots and shuttered local businesses. They even framed the square of beige carpet where Springsteen had stood, the outline of his boots traced in black marker.