On National Forests, Logging Projects Advance With Less Public Input

As the Trump administration rescinds NEPA regulations under an emergency authority to reduce wildfire risk, the Flathead National Forest has begun analyzing logging projects without public comment

By Tristan Scott

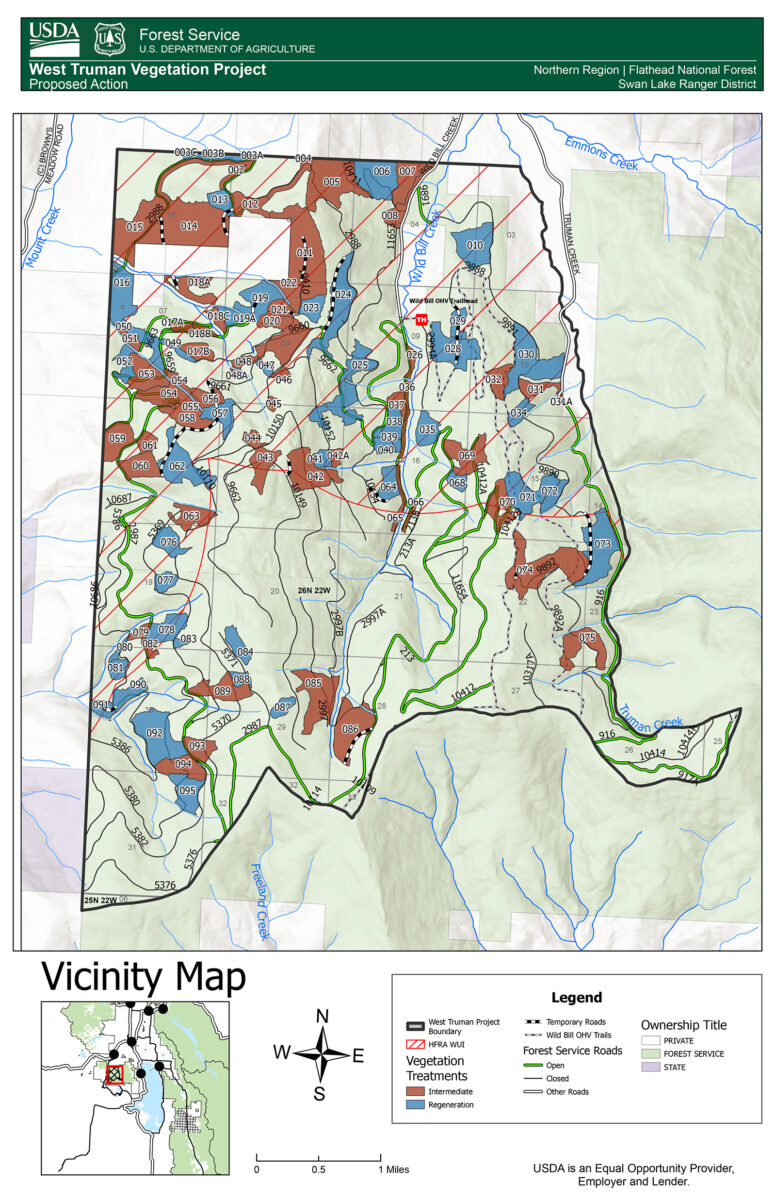

On Oct. 17, more than two weeks into the ongoing government shutdown, the Flathead National Forest’s district ranger in Swan Lake proposed an emergency logging and thinning project west of Blacktail Mountain called the West Truman Project. The project proposal, as well as its stated objective to reduce wildfire risk and contribute to the local timber economy, was published to the Flathead National Forest’s projects website, signaling a departure from the agency’s usual strategy of notifying members of the public about planning projects by email and issuing press releases.

It also came with a caveat: The West Truman Project is being analyzed under the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) newly established Emergency Action Determination (EAD) and, combined with recent revisions to the National Environmental Policy Act, known as NEPA, is exempt from the customary layers of permitting compliance — including an administrative objection period and public comment.

“While there is no formal comment period for this project, your input on the project would be most helpful if it was shared by November 1, 2025,” according to a cover letter signed by Swan Lake District Ranger Sarah Canepa.

The letter was published alongside a proposed action document for the West Truman Project, which calls for logging 2,889 acres of national forestland in the Salish Mountains, with more than half of the 13,017-acre project area falling in the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) established by the Flathead County Community Wildfire Protection Plan.

“All Forest Service lands within the West Truman project area are covered by this Emergency Action Determination,” according to the proposed action. “This document serves as public notice of this authorized emergency action.”

Keith Hammer, the longtime leader of the environmental watchdog group Swan View Coalition, said he wasn’t surprised to see the Flathead National Forest propose a logging project with the stated purpose of reducing wildfire risk; however, he was surprised by the covert way in which they proposed it.

“It appears that the public and perhaps the press must now go hunting on the Flathead’s website each day to stay abreast of the increasing number of timber sales ordered by the Trump administration,” Hammer said. “I’ll give the Flathead Forest some credit: In the past, if you wanted to be involved, you could get on a list and they were pretty proactive about providing you updates to projects. But that’s been gradually eroding, and now it appears they are slamming the door on the public. They’re just not going to let us know anymore.”

Indeed, forest officials are analyzing the West Truman Project through a new lens of compliance that covers millions of acres of National Forest System lands identified as having a high risk of wildfire. Working in concert with regulatory revisions to the National Environmental Policy Act, the new proposed projects are subject to less rigorous scoping, public comment and objection periods in order to fast-track logging projects, improve the beleaguered timber economy and reduce wildfire risk.

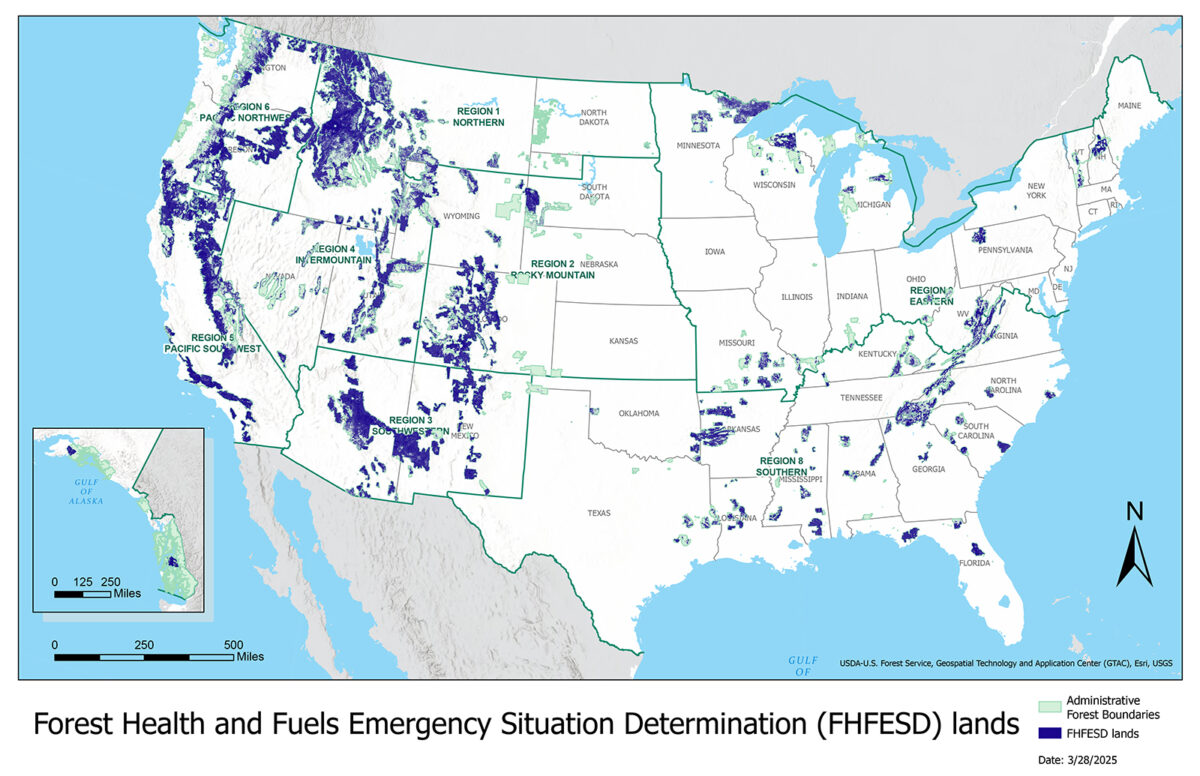

The USDA began scaling back its environmental review apparatus on April 3, when Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins issued a memo designating the use of more than 112 million acres of national forests (about 58% of the total land managed by the U.S. Forest Service) for logging to increase timber production and reduce wildfire risk, including on the Flathead National Forest. The emergency designation allows the Forest Service to expedite approval for logging activity in the designated forests while bypassing the usual processes required under national environmental laws.

It not only shortens the length of environmental reviews, but also limits the public process used by stakeholders to inform how projects are designed, as well as address potential impacts to wildlife habitat, trails, watersheds, viewsheds, and other recreation resources.

Among the proponents of the rules change is U.S. Sen. Steve Daines, R-Mont., who was instrumental in codifying the Forest Service’s EAD authority in 2021. Daines said its recent expansion under President Donald Trump streamlines forest management projects in areas facing an emergency, including in Montana.

“Thousands of acres of National Forest System lands across Montana are at risk of catastrophic wildfires and this expansion will speed up on-the-ground work,” Daines said in a prepared statement on April 7, after the EAD expansion was established.

“Montanans and folks across the West are sick and tired of breathing in smoke. It is refreshing to have a President and USDA Secretary who recognize the dire emergency of wildfires and stand ready to protect our communities by implementing commonsense, science-based forest management projects,” Daines said.

But according to Hammer, folks across the West also like having a say in how their public lands are managed, and the new EAD gives agency officials more latitude to fast-track logging projects without collecting any public input.

“It makes you lose some sleep at night,” Hammer said.

Before pursuing a project or plan that could harm the environment — like through logging, cattle grazing or mining — federal agencies are required to ask the public for input.

Under the Trump administration, federal agencies have steadily limited or curtailed public input, which is required under NEPA.

On June 30, for example, the USDA released an interim final rule changing NEPA implementation procedures for all of its agencies, including the Forest Service. These regulations come in response to the administration’s rescission of the Council of Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) NEPA regulations earlier this year triggered by a Jan. 10 executive order from Trump, called “Unleashing American Energy.” The order instructed each agency to craft its own NEPA regulations during the development of the rule. Then, on July 3, the USDA removed seven agency-specific regulations implementing NEPA, including those for the U.S. Forest Service, and replaced them with new department-wide NEPA regulations.

In response, the Flathead National Forest last month announced that it is “adjusting the way planning projects are announced and public comments are solicited.”

“As a result of these recent changes, the Flathead National Forest is beginning to implement … USDA direction by more efficiently complying with NEPA, especially in regards to projects that address forest health and fuel reduction or other active forest management objectives,” according to an Oct. 14 letter from Flathead National Forest Supervisor Anthony Botello, which explained that “notices of proposed actions (scoping) will no longer be sent by way of email mailing list.”

“I encourage you to look to our webpage as the primary source of project information and updates,” the letter states. “To keep informed, please monitor our project webpage, selecting the project that interests you, and contact the individual listed as the project leader.”

For Hammer, who’s spent more than four decades watch-dogging Forest Service logging projects to ensure environmental compliance — as well as filing lawsuits when he believed the agency was violating its own policies — the agency has over time restored the public’s trust by figuring out ways to involve residents and stakeholders.

“Forty-two years ago when I started monitoring the Flathead National Forest, they were negligent in their duties to involve the public,” Hammer said. “But over time, they came up with some pretty workable solutions and built up a fair amount of public trust. It was a process that was working for everyone. Now, they seem to be deliberately hiding public notices to make it more difficult to know what the heck is going on. It feels like a return to the past, and I think the level of trust they’ve established is going to evaporate in very short order.”