A League of Her Own

Having celebrated her 100th birthday on New Year's Day, Swan Lake resident Donna Roberts is among the last survivors of the original All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, and the only documented player from Montana. As professional women’s baseball makes its long-awaited return, her story offers a rare glimpse into the lives of the pioneers who first proved that women could play on a national stage.

By Katie Bartlett

In 1946, Redbook magazine ran an article far removed from its usual mix of movie recommendations, diet tips, and wartime romance fiction.

It showed young women swinging bats and sliding into bases. They had gathered in Chicago with the dream of joining a new professional women’s baseball league that had sprung up just a few years earlier.

Hundreds of miles away in Billings, Montana, the article caught the eye of 20-year-old Donna Roberts.

The women — a motley mix of clerks, teachers, farmworkers, and homemakers — were vying for spots in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL), later immortalized in the 1992 film “A League of Their Own.” Before Geena Davis and Madonna hit home runs on the big screen, more than 600 real women played professional ball, filling the void left by thousands of male players serving overseas in World War II.

Having crossed home plate to her 100th birthday on New Year’s Day, Roberts is among the last survivors of the original league and the only documented player from Montana. As professional women’s baseball makes its long-awaited return with the arrival of the Women’s Pro Baseball League (WPBL), her story offers a rare glimpse into the lives of the pioneers who first proved that women could play on a national stage.

Roberts’ baseball journey began in Randolph, Nebraska, where she says she grew up as a “competitive tomboy.”

“The girls were always sewing dolls’ clothes, so I tried it once and took a hunk of meat out of my finger,” she said. “So I thought, ‘Okay, this isn’t for me.’”

Instead, she hung out with the boys, shooting marbles and running races. She’d clip-on ice skates, a gift from her grandfather, and join them at a pond during Nebraska’s frigid winters. In the summer, they gathered at a local field to play pick-up baseball.

Her parents didn’t care what she did for fun or who she spent time with — they were focused on making a living and getting through the hardships of the Depression. But in 1930s Nebraska, not everyone shared their open-mindedness.

“I tried to join the team at my school, but the coach and school administrators told me that ‘girls don’t play ball,’ Roberts recalled. “That was the end of the discussion.”

At age 13, her baseball prospects shifted when her father’s work in the cattle trade brought the family to Montana. Billings, a sports hub in the early ‘40s, offered new opportunities.

Local softball enthusiasts had organized a recreational league with five teams that regularly competed against one another. Roberts joined a team sponsored by the popular Bridger Cafe, paying her own way to travel across the state and face teams in Livingston, Great Falls, and Missoula. They made it all the way to the state tournament, where she helped her team claim the championship.

Her softball experiences opened her mind to new opportunities. After reading the Redbook article, she immediately wrote to an AAGPBL organizer to find out how she could apply for a spot on a team. She lived too far from the League’s scouts for a traditional assessment, so the organizer sent her a score sheet to fill out.

“We had no statistics whatsoever, so I gave it to my PE teacher to fill out,” Roberts said. “I don’t know what he wrote, but he must’ve made it look pretty good because they sent me a ticket to training camp.”

Her parents didn’t mind her playing local ball, but the thought of their daughter traveling thousands of miles to a training camp in Mississippi worried them. She’d never been farther east than Nebraska, and there was no telling what would come of the try outs.

Their concerns didn’t stop her. She bought a new bat, packed her bags, and got on the train to Pascagoula, Mississippi.

“My bat was my companion on the train,” she said, recalling a rowdy, exhilarating ride full of people celebrating the war’s end. Her ticket didn’t include a bunk, so she rode upright for the entire multi-day trip. Along the way, she met soldiers returning home and two Canadians, also headed to Pascagoula for training.

When she arrived in Mississippi, she would be among 500 women competing for a chance to play professionally in a league that had already captured national attention.

The AAGPBL had been founded three years earlier by Philip Wrigley, the owner of the Chicago Cubs, who worried about the war’s impact on Major League Baseball (MLB).The draft had gutted the men’s minor leagues, the farm system for new MLB talent, and half of all big league players were also serving. Even stars like Joe Dimaggio traded their pinstripes for camouflage.

As a result, the Office of War Information informed Wrigley in 1942 that it might be necessary to cancel the following MLB season. While the season ultimately went on as planned, he worried that the lower quality of play could make fans lose interest. Always entrepreneurial, he brainstormed ways to help baseball weather the war.

It was the era of Rosie the Riveter and “We Can Do It!” In the spirit of patriotism, women were occupying roles traditionally reserved for men, working in factories, shipyards, and offices, or even joining the armed services. It was the perfect moment for them to step up to the plate.

Wrigley chose four medium-sized midwestern cities close to his parent group in Chicago to host women’s teams. In 1943, he launched the AAGPBL, providing affordable, local entertainment in the pre-television era. When Roberts arrived in Mississippi in 1946, the League was drawing more than 450,000 fans in a season.

Training began at 8 a.m. sharp every morning. The women ran drills, practiced batting, and honed their fielding skills under the watchful eyes of the managers. Between sessions, organizers passed out sack lunches, which the players scarfed down in the bleachers. They collapsed in bed each night, exhausted after long days of playing.

Roberts doesn’t remember much camaraderie among the women trying out. Most didn’t know each other, and their priority was impressing the managers — not making friends.

“Girls were sent home every day,” she recalled. “You were really very internally focused only on how you were doing.”

During one assessment, Roberts threw an underhanded ball to first base, trying to get it there as fast as she could. She didn’t yet know the first basewoman, who had a reputation as an “old hand” in the AAGPBL. After the game, the woman approached her.

“She told me, ‘don’t you ever throw an underhand to me again,’” Roberts recalled. “It was a little startling.”

At the end of the two-week training camp, women swarmed to a posted list of approximately 120 names, rapidly scanning for their own.

Roberts wasn’t worried. She knew she’d find her name.

“I’m a very confident person — I’d been playing for a long time, and I really felt good about what I could do,” she added.

The Rockford Peaches. The Fort Wayne Daisies. The Racine Belles. Then, under the heading for the Peoria Redwings, she saw it: Donna Stageman — the name she had played under before she married.

Roberts became part of the inaugural Redwings lineup. As the League grew in popularity, Wrigley looked to expand it closer to Chicago. Peoria, Illinois was less than 200 miles from the city and had a strong local baseball scene, making it the perfect place for a new team.

Roberts and the other AAGPBL rookies loaded onto buses for their first exhibition tour through the South. In Florida, they faced a local team before a long trip to Texas, where rain washed out the game — and with it, their chance to see the Alamo. Nearly 80 years later, Roberts still regrets she never got to see the historic fortress.

In Mississippi, train cars awaited to carry the women north to Wisconsin, Indiana, and, for Roberts, Illinois. Officially an AAGPBL player, she no longer had to sit upright for hours on the train. The women rode in Pullman cars, known as “hotels on wheels” for their plush seating, velvet curtains, and convertible seat-beds.

When Roberts stepped off the train in Peoria, her first task was finding a place to live. A widow who lived near the stadium offered her a room. The woman took on a caretaker role, cooking, washing Roberts’ clothes, and sending her off to practice each day.

Roberts played shortstop and center field on an $80 per week contract — the equivalent of more than $1,300 today.

Peoria didn’t have a proper baseball stadium, so the League set up a makeshift diamond inside the local football field. Right field sat unusually close to home plate, making it easy to hit the ball out, while left and center stretched deep. It made for uneven, lopsided play.

Even so, the games drew crowds. Roberts remembers upwards of 500 people showing up for home games, filling the stadium and lining the fence.

Male fans often dismissed the League at first, but their attitudes shifted as soon as the women started warming up. Their laughter faded, replaced by comments like: “Holy cow, she throws like a man!” or ‘I’m gonna go get my dad. He’s gotta see this.”

The Redwings didn’t have a strong inaugural season — they finished 33–79 — but Roberts’ best memories from the games weren’t about wins or losses.

At the end of each game, little girls would rush down from the stands and flood the field, hoping to meet the players and get their autographs.

“I suppose they all felt that eventually that’s what they might do,” Roberts said.

Life on the road was quiet and focused. The women typically went straight home after practice, and Roberts’ memories of Peoria — and the other midwestern cities the team bused to — are mostly of the baseball diamond. The most novel thing she remembers from the road? A restroom in Florida with an illuminated toilet seat.

“I can’t really remember what we did for fun, except that we were tired,” she added. “When you traveled all those distances and played ball that frequently, you weren’t living it up very often.”

Even nights off weren’t completely free. Chaperones, hired by Wrigley to maintain the League’s wholesome image, closely monitored the players at all times. When Roberts went out with a sailor, she had to report to her chaperone, who set strict limits on how long she could be gone and where she could go. The chaperones’ job, she recalled, was “to be on you all the time.”

All of this helped enforce a clean break from the players’ former lives. Boyfriends were never discussed — most of them were off at war — and Roberts doesn’t even know where the majority of her teammates were from.

“There were no great romances, and home was never part of our conversation,” she said. “It was purely baseball all the time.”

The league, however, demanded more than skill on the field. Roberts recalled expectations to “play like a man, look like a lady,” a maxim spelled out in the AAGPBL handbook.

“Every effort is made to select girls of ability, or real potential, and to develop that ability to the fullest potential,” the League manual read. “But no less emphasis is placed on femininity.”

That meant strict rules both on and off the field: “boyish bobs” were not permitted and lipstick was required. League officials barred players from smoking, drinking and wearing shorts or slacks in public, even when not partaking in AAGPBL activities.

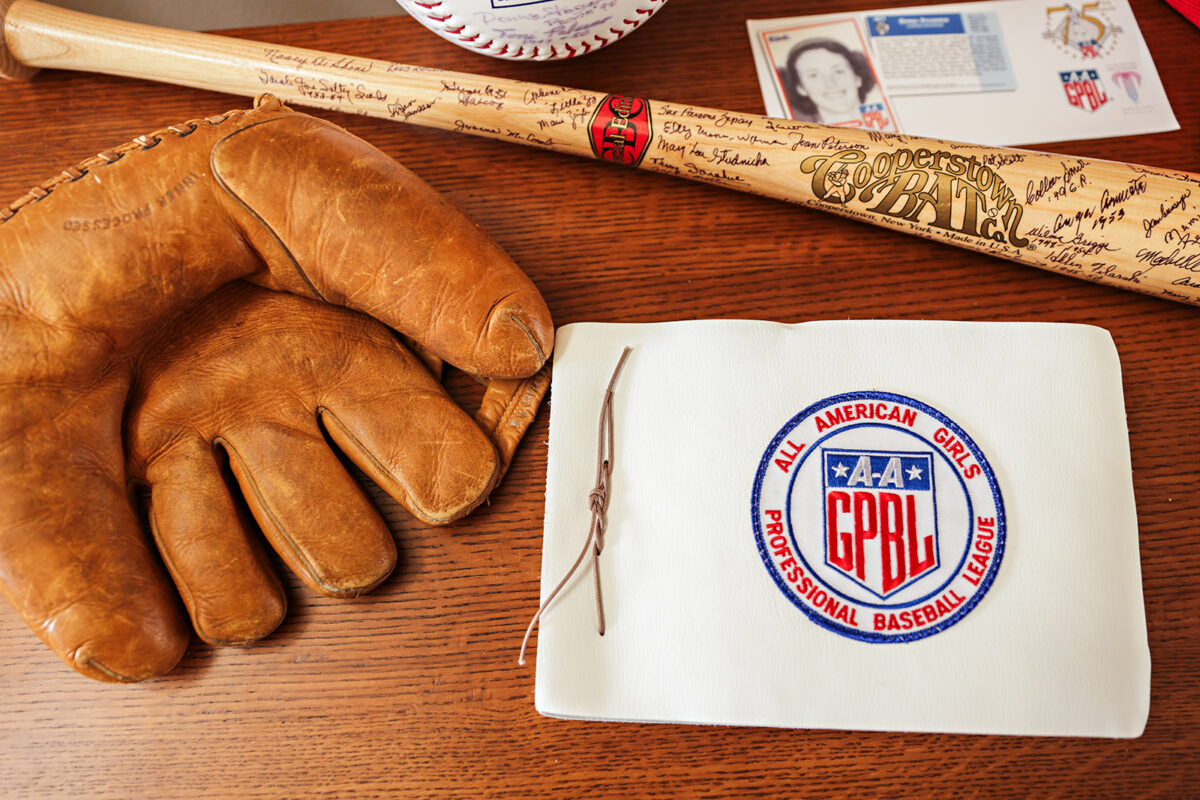

The most lasting cultural legacy of the AAGPBL’s femininity rules is the uniform. Roberts continues to see girls on Halloween dressed in the iconic outfit: belted tunics with a short, flared skirt and red shorts worn underneath, true to the style immortalized in “A League of Their Own.”

But the uniform came with a painful trade-off. Sliding during games often left the women with nasty abrasions known as “strawberries,” which rarely healed before they were ripped open again.

For the players, the discomfort of the dresses was simply the reality of playing baseball as a woman.

“If you wanted to be in the league, the uniform was something you just had to accept,” Roberts said. “You really tried to avoid sliding because of that.”

For Roberts, the expectations around obedience — to keep quiet and not question authority — were much harder to swallow.

Back in Billings, her teammates routinely looked out for one another and gave feedback on each other’s playing. Roberts carried this mindset with her to the AAGPBL.

In the middle of the season, she noticed that the team’s Canadian catcher was growing sore from spending entire games in a deep crouch. She approached the manager and suggested he give the catcher a rest to avoid injury.

He did not appreciate her advice.

“He thought I was trying to take over the team,” she said. “That wasn’t something he’d ever allow.”

A few days later, Roberts was catching fly balls during a routine practice when she heard her name announced through a megaphone, calling her to the team office. There, she learned that the manager had ordered her dismissal.

Filled with disbelief, Roberts went home to pack for the trip back to Billings.

“When I got to the train platform, I was crying until tears were falling on the floor,” she added.

Two women officials from the League saw her and asked what had happened. Roberts explained the disagreement with her manager. After she returned home, she learned the women had fired him.

Her teammate Thelma “Tiby” Eisen took over the team for the rest of the season — a move that would eventually make her one of the first women to manage an AAGPBL team.

Years later, Roberts learned that Eisen had tried to find her in Montana to invite her back to the Redwings. In an era when phones were still a luxury item, she never succeeded. Roberts says she wouldn’t have returned anyways.

“I was so disgusted by the way they let me go that I didn’t want anything to do with them after that,” she said. “I would do it all the same way again and keep standing up for my teammates.”

Eight years after her departure, the rest of the AAGPBL players also hung up their bats. Attendance was dwindling to its lowest point in a decade. As people became more mobile and television began to replace live entertainment, the league struggled to draw crowds.

The postwar social order also played a role. Men returned home, bringing the old norms that pushed women out of the workplace and back into kitchens and nurseries — a shift that extended to the diamond. The AAGPBL played its final games in 1954, marking the last time women would play professionally for decades.

With the league gone, Roberts slipped back into her former life. She returned to the Billings softball league, and the money she earned while playing went toward tuition at Eastern Montana College. She married and raised two children, devoting 35 years to a career as an elementary school teacher in Helena.

Her time in the League influenced her approach to teaching, which always included an emphasis on sports and time outside. Her male colleagues would grumble when her third or fourth grade classes would consistently outperform theirs in baseball and other sports.

“I tried to teach them to not be afraid of the world, to just get out there,” she added.

For years, Roberts kept her AAGPBL memories to herself. Her softball trophies gathered dust in a basement box. Her daughter, Susie Johnston, didn’t hear a single story about the league throughout her childhood. She was in her 20s when she first learned her mother once played professionally, soon after “A League of Their Own” came out.

Roberts wasn’t unique in her silence. She says many women who played never discussed that chapter of their lives upon returning home.

“It wasn’t celebrated the way it is today; it was just something that we did,” she said. “And when it was over, we went home and lived our normal lives.”

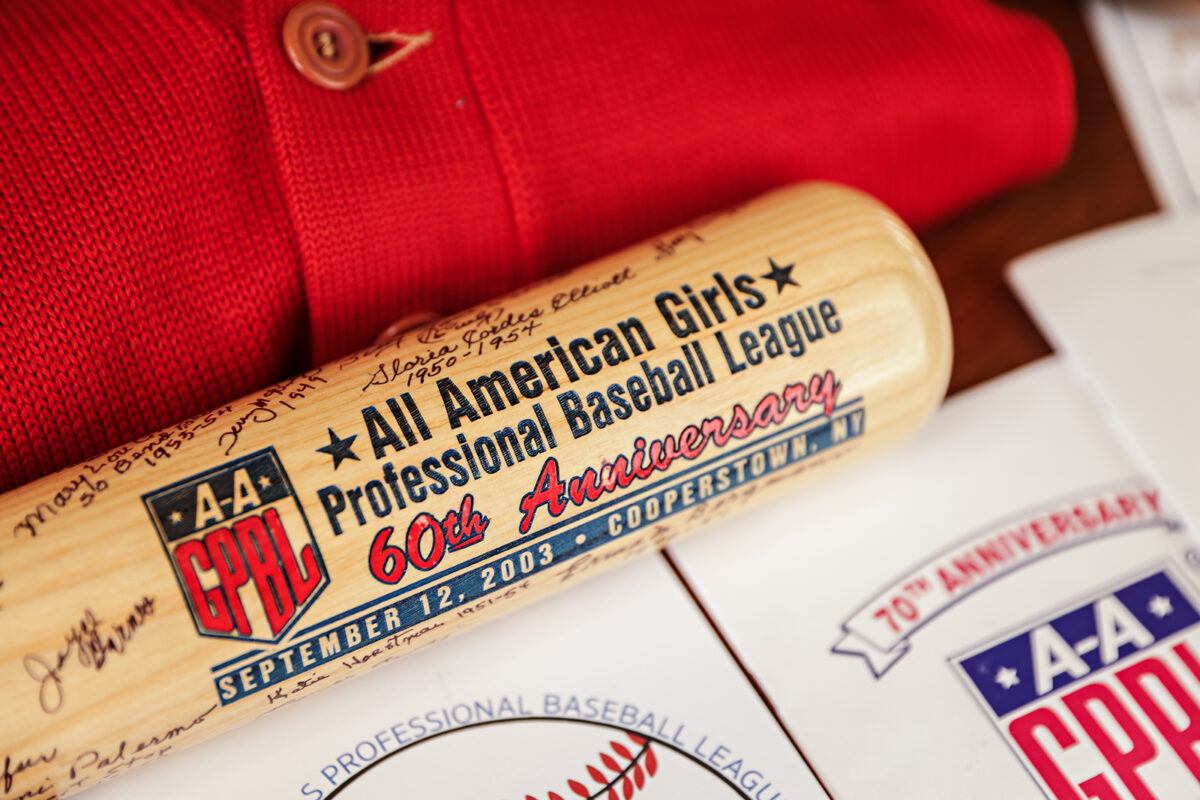

That began to change with the film, which rekindled a piece of history that Roberts and others had left behind. After it came out, League reunions exploded in size — not just with returning players, but with fans eager to hear their memories. This past July, Roberts signed autographs for an hour and a half at a reunion.

When the movie first came out, Roberts says she wasn’t “the least bit excited” to see it — her daughter, Susie, was the one who insisted. Still, she found it to be a faithful portrayal of life in the League and especially enjoyed the scenes where the women ran the bases.

“The movie is built on emotion rather than actual skills, and I think those scenes are not only hilarious but capture the feeling of playing,” she said. “It’s really that emotion that carries the film.”

Her one qualm, however, was Tom Hanks’ portrayal of Jimmy Dugan, the alcoholic manager who dozes through games, urinates in public, and berates his players. Like Dugan, her own manager, Wilbur “Rawmeat Bill” Rodgers, was a former major leaguer, but their similarities ended there.

Roberts and Rodgers had their differences, but she says he never would’ve barged into a locker room or passed out drunk during a game. “There’s no crying in baseball!” may be a myth.

“The managers I knew of would never talk to the players in such a way,” she said. “They were serious about the game and about winning — and treated us as such.”

Members of the cast have stayed in close contact with the League’s survivors. Roberts met director Penny Marshall several times. Tom Hanks would send the women notes. Through a meeting with actress Patti Pelton, Roberts and her daughter learned that the high stakes behind the film echoed the real challenges that AAGPBL players faced.

“She told us the film was a make-or-break project for [Marshall],” Johnston said. “Like my mom, she was a woman in a man’s field — and it would’ve destroyed her career if the movie had flopped.”

Since the film came out, Roberts has attended more than a dozen AAGPBL reunions, which draw former players from across the country. She started going out of curiosity — and with the hope of finding old teammates.

At one reunion, she got to meet the Canadian catcher she had once stood up for, though the player didn’t remember her. At another, she brought her daughter and grandchildren to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, where her glove and shoes had been on display for many years. It was “surreal,” Johnston said, to see her mother honored there.

But the gatherings are shrinking. Roberts remembers her first reunion as crowded with dozens of former players. This year’s event had only eight attendees, and fewer than 30 of the League’s women are known to be alive today.

“There’s been a lot of conversations recently about who is going to keep preserving this history and telling our stories once we’re all gone,” she said. “It’s guesswork — I don’t know the answer, and I don’t think anyone else does either.”

But at July’s reunion in Durham, North Carolina, the spirit of the AAGPBL was alive again. As culture increasingly celebrates women in sports and leagues like the Women’s National Basketball Association draw cult followings, the Women’s Pro Baseball League (WPBL) is set to launch in 2026. Elite players competing for spots in the new League had the opportunity to showcase their skills at the reunion for those who came before them.

Roberts and other AAGPBL alumni watched from the observatory, drinks in hand, as young players took the field. She wasn’t overly impressed — and was sure to let a scout observing the women know that the players were better in her day. But even so, she believes the WPBL is “a great move for today’s women.”

“I never imagined there’d be another generation of players like us,” she added. “If I could tell them one thing, it would be to go right ahead without any thought of any barriers.”

Roberts has followed her own advice. Aging hasn’t slowed her down — she competed in the Senior Olympics until age 97, winning plenty of gold medals. She jokes that they “didn’t have much choice,” since she was often the only competitor in her age group.

These days, she splits her time between Helena and Swan Lake, surrounded by her children and grandchildren, who like to remind her she’s “older than sliced bread,” first sold two years after she was born. Although she’d been looking forward to turning 100 on New Year’s Day, Roberts plans to “keep enjoying life” for at least another ten years.

Years after her baseball career ended, Roberts holds onto the most important lesson the League taught her — what she calls “straight thinking.”

“We had to think for ourselves,” she said. “Whether you’re playing a sport or not, don’t be so controlled by outside influences that they disturb your life.”

It’s advice she’s lived by for a century.