Written in the Land

Sally Thompson’s ‘Black Robes Enter Coyote’s World’ grew from her work on the Clark Fork Superfund case. But the book itself reaches back to the first encounter between the Salish and Jesuit missionaries, where radically different ways of understanding land collided — with consequences that continue to unfold.

By Erika Fredrickson, The Pulp

The Upper Clark Fork River Basin holds a complicated history and, for a long time, it was a story impossible to ignore. After more than a century of copper smelting in Butte and Anaconda, toxic waste settled into its waters and soils, altering ecosystems and the lives that depended on them. By the 1980s, the damage was written plainly across the land. For Indigenous nations whose lives and treaties were bound to that basin, the contamination marked yet another line in a much longer ledger of broken promises and deferred responsibility.

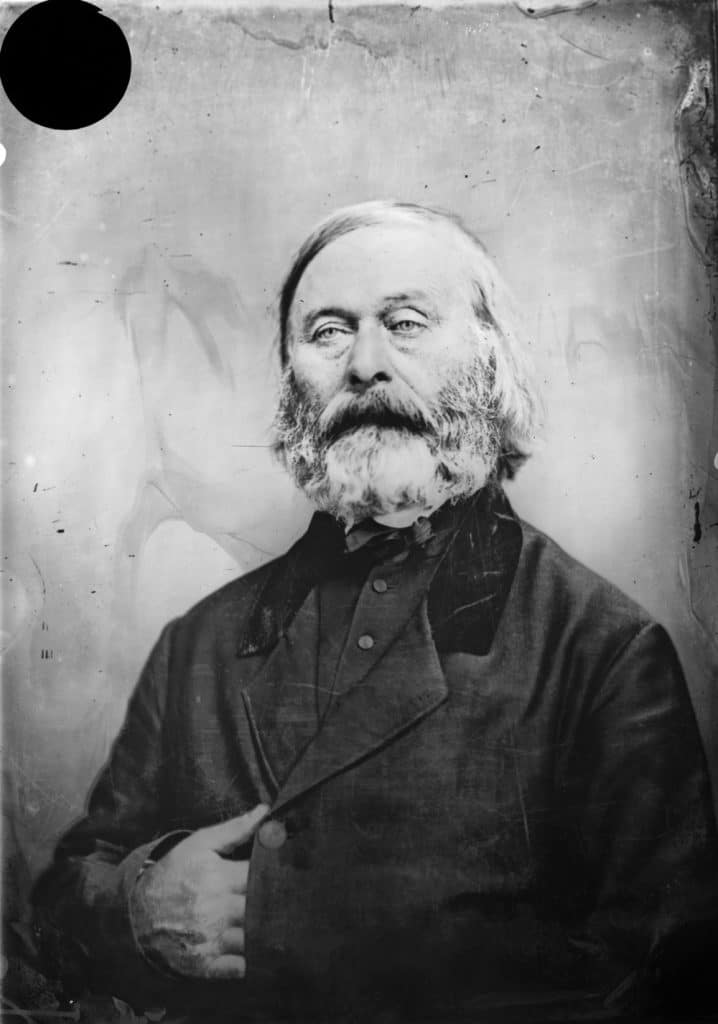

Sally Thompson spent years reconstructing this history as an expert witness for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in their case against the companies responsible for befouling the river basin. But the work led her somewhere unexpected: to a Belgian Jesuit named Pierre-Jean De Smet, and to questions about what happens when fundamentally different worldviews collide. Her new book uses that 19th-century encounter between Jesuit missionaries and the CSKT in the Rocky Mountains to examine competing ideas about land, responsibility, and what we owe the places we inhabit.

The pollution traced back to the Anaconda Company, but by 1983 it was ARCO facing lawsuits from the state and, later, from the EPA — litigation that would stretch into one of the largest Superfund cases in U.S. history. The case ultimately forced a corporate successor to pay billions of dollars in long-term remediation and restoration. But it also asked a deeper question. For the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, the contamination of the Upper Clark Fork wasn’t just environmental harm, it was treaty violation. It was a disruption of lands and waters they had never ceded, which were also lands and waters they were tied to for survival.

In order to make their case, experts were asked to reconstruct a history of the basin that stretched far beyond corporate ownership or statehood. What did this place provide? Who used it? What changed, and when? Answering those questions meant reading the landscape as evidence and digging into the paper trail left by missionaries, traders, settlers, and government officials who often described the same places in radically different terms.

To be able to deeply dig into the history along this river and learn about the incremental and more massive changes through time — I felt like I grew roots by doing that work.

It was during the ARCO lawsuits that Sally Thompson first encountered the story of Father Pierre-Jean De Smet. As an expert witness she was tasked with helping determine the scope of the CSKT’s off-reservation treaty losses along the river. That job required working with Salish elders and homesteader descendants, as well as reading everything she could find, from government records to missionary journals, in order to reconstruct what the basin had once provided and how it had changed.

“It was an incredible project,” Thompson says. “We really created an incredibly strong case for their loss. To be able to deeply dig into the history along this river and learn about the incremental and more massive changes through time — I felt like I grew roots by doing that work.”

The ARCO litigation stretched nearly two decades, concluding with a final settlement in 2008. But the questions about land, responsibility, and worldview did not begin with ARCO and they did not end with the settlement. For Thompson, they were just beginning.

She learned that De Smet was a Belgian Jesuit who established the St. Mary’s Mission in the Bitterroot Valley in 1841 and also the St. Ignatius Mission in 1854, on land that would later become the Flathead Indian Reservation. And it intrigued her. How did this man from Belgium end up here, at this particular moment?

When De Smet arrived, the region was still Indigenous-governed, but it was already under strain. Disease, the fur trade, and expanding colonial pressure had begun reshaping daily life and belief systems. Within that disrupted landscape, some tribes began requesting Catholic missionaries, known as “black robes,” not as a rejection of their own cultures, but as a strategic and spiritual response to a world already altered by outside forces.

“At that time there were some missionaries on the coast getting started,” Thompson says. “But this really was the last best place. Nothing had been built that was permanent. There was no ground disturbance. The life of this place was still pretty intact. And I was fascinated by that juncture.”

She was also struck by how De Smet had been remembered.

“Everything written about him was close to sainthood,” she says. “It was all written by Catholics who had such great admiration for him. And that’s never a full picture, right?”

At first, Thompson imagined a book that would literally follow De Smet — tracing his movements across North America and Europe. With grant funding, she traveled widely, digging through Jesuit archives in Rome, visiting De Smet’s hometown in Belgium, and working through collections across the United States.

But once she began writing, the project shifted. She wasn’t interested in tracing the path of a single man who had already been extensively, if incompletely, documented. What mattered more was what De Smet represented: a moment of encounter, and the vastly different worldviews that met there.

Letting go of De Smet as the organizing center changed the scale of the book. An early draft ballooned — spanning continents and centuries — until a reviewer urged her to focus. Why not center the Salish, they suggested, and let the other threads move through that lens?

“Oh, man, I had to really rewrite it again,” Thompson says. “I’ve been at this for a long time. But I don’t regret the stuff I learned, because it informed everything. It informs my life and choices.”

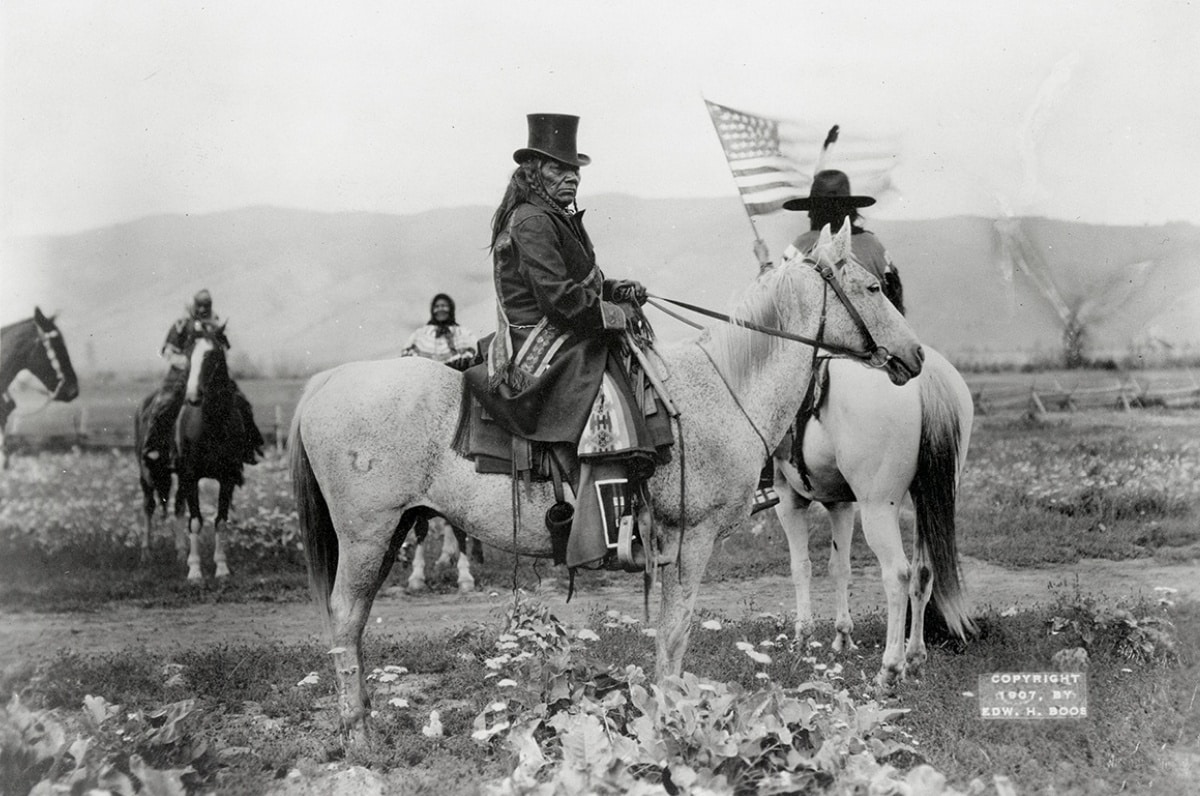

What emerged was “Black Robes Enter Coyote’s World: Chief Charlo and Father De Smet in the Rocky Mountains,” published by the University of Nebraska Press. It’s a book grounded in a specific place and people, but animated by much larger tensions about migration and belonging. De Smet remains in the story, but he is no longer the point. He is a doorway.

The book begins with Salish leaders encountering Jesuit missionaries at a Potawatomi mission along the Missouri in 1839. And, from there, Thompson follows how those relationships unfolded across the lifetime of Salish Chief Charlo when two very different ways of understanding land were forced to coexist.

Thompson has been circling those kinds of themes for most of her adult life. An anthropologist who moved to Missoula in 1980 to help start the archaeology program at Historical Research Associates, she eventually shifted away from excavation and toward long-term collaboration with Native communities, including Taos Pueblo, the Blackfeet Tribe, and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

It was while working alongside Taos elders on a water rights project that she first heard an Indigenous viewpoint on the “covenant of the creator.” In Western Christianity, “covenant” often emphasizes humanity’s obligation to God, with the natural world as a backdrop or resource. For the Taos and other Indigenous cultures, the “covenant of the creator” is referring to the sacred and reciprocal relationship with their Creator and the natural world, emphasizing stewardship and interconnectedness.

In her 2024 book “Disturbing the Sleeping Buffalo,” Thompson uncovered hidden histories, and some of those tidbits informed “Black Robes,” too. One hidden history was the origin of Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” theory. This theory on understanding human motivation and behavior came from observing Blackfoot community members while spending a summer in Siksiká, Alberta. There, he witnessed a completely different view on shame and competition.

“There was never shaming,” Thompson says. “Ever.”

When Maslow asked a young man who the best singer was — singing being central to community life — the question itself seemed incomprehensible.

“He finally said, ‘Everyone is good.’ He couldn’t even fathom why you would turn that into a competition.”

Besides these anthropological examples, Thompson wrote “Black Robes Enter Coyote’s World” from primary documents. While in St. Louis for the final Lewis and Clark Bicentennial event, Thompson stopped by the special collections at Saint Louis University and asked, almost casually, if they had any De Smet material.

The archivists hesitated. In fact, a box had just come in. Nobody had looked at it yet, but they allowed Thompson to open it. Inside was an unprocessed, lizard-skin field journal De Smet kept during the winter of 1858–59, while traveling the Clark Fork River.

“To see his own field journal,” Thompson says, “and then compare it to what is published — reading between the lines, comparing government documents, personal journals, other people’s reports — you still don’t get the full picture. But you get closer.”

The deeper she went, the more De Smet’s carefully cultivated image complicated itself. He was not simply a resident missionary, but a skilled writer, mapmaker, fundraiser, and ambassador — someone who spent surprisingly little time actually living among the people whose story became entwined with his name.

Still, Thompson resists flattening him into a villain. For his map that was used in the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty, De Smet circled land for tribal territories, which had not been done before and helped set aside protected land for the tribes in ways that shaped history. Thompson says that De Smet seemed to empathize with the tribes’ difficult situation in the face of colonization. His viewpoint was that it was inevitable and reservations would provide the best outcome.

“And I’ve come to think that, in a way, he was right,” Thompson says. “I’m an idealist and kind of wish that somehow people had escaped what was inevitable, but with the expansion and land-acquisition ideal, it was inevitable,” she says. “And perhaps he did help soften the blow here compared to some other places.”

What history has made less room for, she argues, are leaders like Chief Victor and Chief Charlo — diplomats rather than warriors, negotiators rather than symbols.

“We like war stories,” she says. “We define eras by wars. We rarely ask who we’d be if we focused instead on diplomacy.”

That question sits at the heart of “Black Robes Enter Coyote’s World” and lands with particular force when Thompson describes a speech Charlo gave in 1876 — a moment that became a pivot point in her writing. Speaking to his people, Charlo wonders about white men’s greediness. He describes them as orphans — needy, never satisfied. Cast out from their place of creation “He compares them to wolverines,” Thompson says. “They’ll steal your cache and then come back for more.”

Charlo compares them to wolverines. They’ll steal your cache and then come back for more.

Cut off from their place of origin, carrying beliefs shaped by exile rather than relationship, helped explain — to Charlo — why white settlers moved through the land seeking to transform it rather than belong to it.

As a non-Native author, Thompson’s book required constant checking, humility, and consent. She shared drafts with the Salish spiritual leader Johnny Arlee and with Bitterroot Salish elders, asking directly whether she should continue. Arlee, whose blurb for the book calls it “honest and respectful” told Thompson that his own people didn’t know this story well. “Please publish it,” he told her.

“Black Robes Enter Coyote’s World” closes with Charlo’s death and the devastating Allotment Act, which broke communal tribal lands into individual parcels to force assimilation. But Thompson was determined not to end the book with loss alone. In the epilogue, we learn how the Salish bought back land and are now restoring the Jocko watershed using the settlement money from ARCO. Reciprocity, responsibility, and collective good are not artifacts. They persist.

“If we don’t reconnect with the living world and the spiritual world — which is really just life — we aren’t going to make it, ultimately,” Thompson says. “Because we’re so destructive without that covenant.”

That insistence on connection — not conquest — has resonated widely. In 2025, “Black Robes Enter Coyote’s World” received the Big Sky Award from the High Plains International Book Awards, a gold-level Will Rogers Medallion Award, and was named a finalist for the High Plains International Book Award in Nonfiction — recognition that sent Thompson on the road for much of the year, sharing a story rooted deeply in this place, and urgently relevant beyond it.

The book is not a verdict. It is an invitation to notice the worldviews we carry with us into the landscapes we inhabit.

“And maybe,” Thompson says, “we decide where we put our attention when we wake up in the morning. Are we going to worry all day about what’s happening far away, in Washington D.C.? And eat away this beautiful day? Or tend to what’s here, in our community, and in our hearts?”

This story originally appeared in The Pulp, which can be found online at thepulp.org.