Stakeholders Weigh in on Granite Moccasin Logging Project

Proponents say the Flathead National Forest's proposal would reduce wildland fire risk and improve forest health in a critical infrastructure corridor along the Middle Fork Flathead River. Meanwhile, conservation organizations are pressing for more environmental review in a 67,536-acre project area that includes a Wild and Scenic River designation, proposed wilderness and roadless lands.

By Tristan Scott

A proposal to use thinning and prescribed burning to remove vegetation across portions of the Flathead National Forest bordering the Middle Fork Flathead River has gained wide attention for its inclusion of sensitive management areas in the project’s 67,536-acre footprint, which provides wildlife with critical habitat while affording paddlers, packers, hikers, hunters and skiers with one of the region’s most popular havens of outdoor recreation.

But even as conservation groups push for additional layers of environmental review, proponents of the project, including wood products industry leaders, recreation advocates and residents, say it’s needed to reduce the risk of wildfire in a corridor brimming with untreated fuels that threaten infrastructure and communities on U.S. Highway 2, as well as to support local timber mills and improve forest health.

If approved, the project would occur in recommended wilderness areas, although the scope of that work would be confined to whitebark pine restoration, tree planting and prescribed burning. Other project activities would occur in inventoried roadless areas, where much of the work also centers on whitebark pine restoration, while others still would be authorized in a congressionally designated wild and scenic river corridor and in core grizzly bear habitat.

Flathead National Forest officials proposed the Granite Moccasin project as an authorized emergency action, and while there is no formal public comment period, Hungry Horse District Ranger Rob Davies, who would oversee the project, urged people to submit feedback by Jan. 15. Additional information about the project and instructions on how to comment is available on the Flathead National Forest project webpage.

In addition to mitigating the risk of wildfire by clearing out a backlog of dead and dying trees, Davies said the project is “designed to improve species composition and tree vigor” by reducing density and removing trees dying of root disease and beetles, which have caused widespread tree mortality across the project area.

About 2,364 acres of the entire project area is proposed for commercial treatment, while 2,345 acres is proposed for noncommercial treatment, and Davies identified supporting the local timber economy as one of its purposes and needs. The project would also require the construction of 7.6 miles of new National Forest System roads.

Opposition to the project has centered on the road building, which conservation advocates said runs counter to project’s intent to mitigate wildfire risk, as well as to the actions proposed in protected areas.

Greg Schatz, of the Back Country Horsemen of the Flathead, said evidence shows that fuel thinning projects have little effect at slowing the spread of wildfire, while citing evidence that the majority of human-caused wildfire starts within a quarter mile of roads.

“While removing trees that can strike power lines may help prevent wildfires, logging and thinning forests actually makes them drier, windier and more prone to rapid fire spread,” Schatz said in his comments.

Keith Hammer, chair of the Swan View Coalition, said road building and culvert failures have already contributed to increased sedimentation in westslope cutthroat and bull trout habitat in the project area, and he opposed the project being “fast-tracked” under new emergency authority authorization that demands a lower level of analysis under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA). He encouraged agency officials to select a higher tier of review and prepare a full environmental impact statement (EIS).

“Simply put, this [proposed action] is expansive and proposes significant impacts in sensitive areas,” Hammer wrote in comments to the Flathead National Forest. “You are trying to sneak non-emergency actions into an [emergency action determination] project in order to dismiss the requirements set forth in NEPA and other laws and regulations. This is unlawful and destroys public confidence in the agency.”

Tom Partin, of the American Forest Resource Council (AFRC), said the Granite Moccasin project “fits very well” within the intent of the emergency authorization authority due to its proximity to essential infrastructure. That includes the BNSF railroad, power lines operated by Flathead Electric Cooperative and Glacier Electric, gas lines managed by Northwestern Energy, and multiple Department of Transportation maintenance facilities. In public comments, Partin and the AFRC encouraged the Flathead National Forest to expand the volume of commercial treatment it’s proposing and “reexamine additional acres that might be suitable for commercial harvest.”

“We do not believe the purpose and needs for the project can be met unless there is a more robust commercial component,” according to Partin. “When the non-commercial treatments are added in, the total acres treated is only 4,689 acres, or 7% of the project area.”

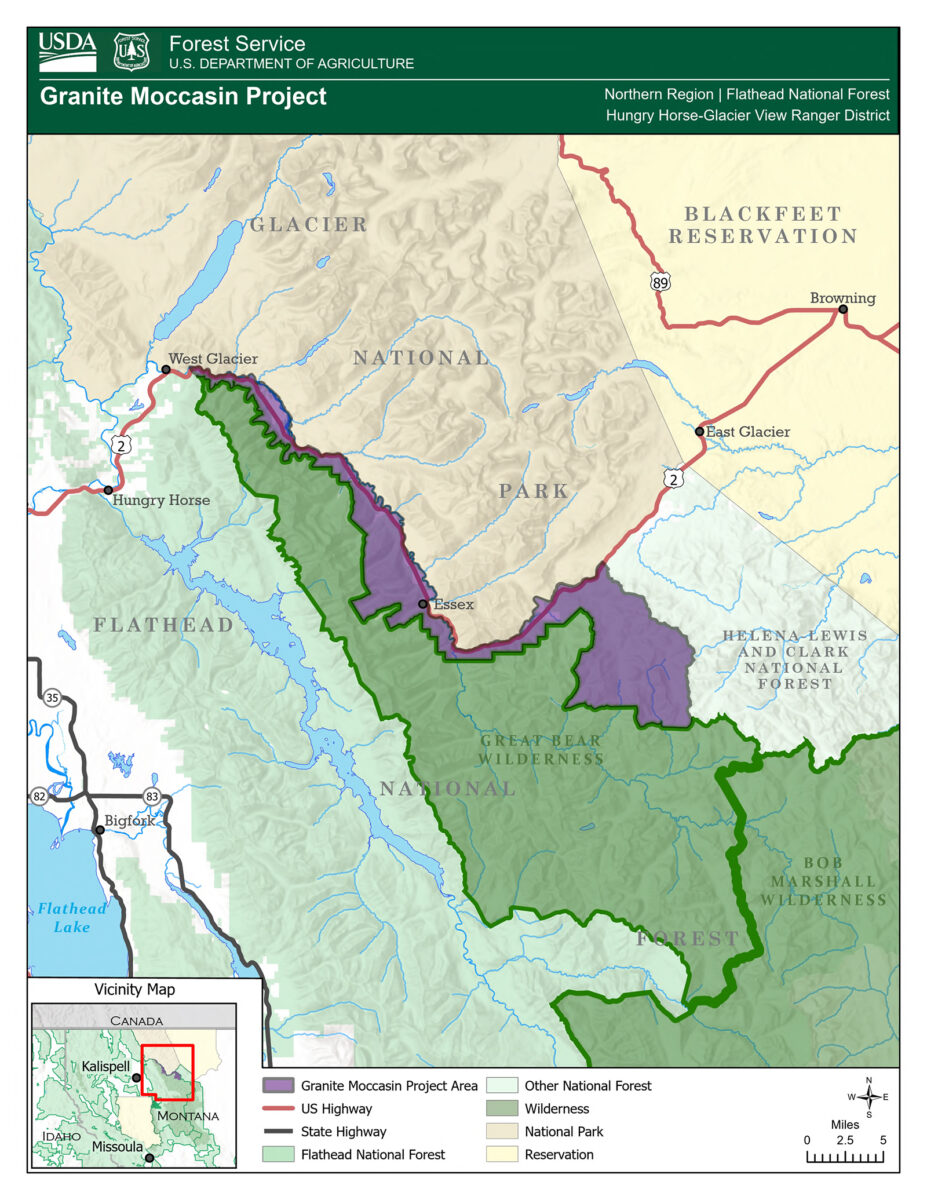

Bordered by Glacier National Park to the north and the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex to the south, the project area spans the length of the John F. Stevens Canyon along U.S. Highway 2. Called the “Granite Moccasin Project,” it is named for two prominent tributaries of the Middle Fork Flathead River, which bookend the project area and serve as popular access sites for boaters. The project area also includes the communities of Essex, Pinnacle and Fielding, and provides a “vital transportation corridor” between the Flathead Valley and the northern plains of eastern Montana, according to forest officials, with the narrow canyon providing the only vehicle-accessible route.

The potential for severe wildfire in the project area is a prominent concern.

Ranger Davies said historical fire records show a pattern of intense activity followed by a long lull and recent resurgence: over 21,000 acres included in the project area burned between 1893 and 1929, followed by minimal activity until 1998, when over 6,000 acres burned. Subsequent large fires, including the Sheep (2015) and Paola Ridge (2018) fires, consumed over 5,000 acres and posed significant threats to local communities and infrastructure.

Historic buildings, such as the Izaak Walton Inn and the Walton Ranger Station of Glacier National Park serve as key tourist attractions and preserve valuable regional history. The concentration of infrastructure, private property, and historic sites contributes to the area’s designation as wildland-urban interface (WUI).

And while critics of the project have seized on its inclusion of 41,470 acres of designated roadless lands, representing 61% of the project area’s land base, and 14,203 acres of recommended wilderness, comprising 21% of the land base, some proponents frame it as an example of how environmental protection measures can dovetail with active forest management. The decades-old Roadless Rule policy, which the Trump administration has taken steps to rescind, generally restricts road building and timber harvests on national forest lands, but it allows some logging to reduce fire risk, improve habitat or aid in the recovery of endangered species, including whitebark pine.

“We are pleased to see that vegetation management is proposed on up to 2,250 acres in roadless areas, including prescribed fire, commercial thinning, noncommercial thinning, and white bark pine restoration treatments,” Partin said.

“No road construction would occur in roadless areas to accomplish these activities,” which he added “will be consistent with the Roadless Rule.”

Referencing the proposal to conduct vegetation treatment in a Wild and Scenic River corridor, which includes about 102 acres of utility corridor expansion, AFRC said timber harvesting is allowed for “multiple-use purposes and to achieve the agency’s desired vegetation conditions.”

“AFRC believes that those who enjoy the Wild and Scenic areas in this project area would rather see green thinned and managed forests than burnt black areas of devastation as they float on these bodies of water, and actions should be taken to prevent devastating wildfires in these areas,” Partin said.

The forest plan also permits “limited human influence” in recommended wilderness areas to preserve the values and characteristics of the land, and the Granite Moccasin proposal limits the type of machinery and harvesting techniques that can occur in the project area.

For AFRC, those limitations are overly restrictive and called for flexibility to “allow a variety of equipment to the sale areas.”

“We feel that there are several ways to properly harvest any piece of ground, and certain restrictive language can limit some potential operators,” Partin said. While the proposal calls for cable harvest in some recommended wilderness, Partin said “there may be opportunities to use certain ground equipment such as fellerbunchers and processors in the units to make cable yarding more efficient.”

Michael Reavis, a longtime Essex resident who has worked in the woods as an avalanche forecaster, wilderness packer, Nordic ski groomer, said he agrees with the project’s overarching objective to promote active management and create a healthy landscape in a region with a legacy of logging.

“I’ve seen a lot of provocative headlines that hint at doom for the wild things, their habitats, and their migration corridors, (i.e. ‘roadless areas,’ ‘proposed wilderness,’ ‘wild and scenic’),” Reavis wrote in comments to the Flathead National Forest, some of which he shared in a social media post and gave the Beacon permission to cite. “These keywords evoke an emotional response in people and before they even get to dig into the facts, they have a visceral, emotional reaction and their mind is seemingly made at a moment’s notice. I get it. I love wilderness. I love the fact there’s wolverines, lynx, bears, wolves, goats, elk, deer all moving about the landscape right out my door. I’ve observed endangered animals using decades-old logging roads for travel. I’ve also watched lynx slowly disappear from the Essex area as the forest has grown too thick, too old for snowshoe hares to thrive. Is this natural? No. The Nordic trails in Essex were once logged. Having groomed the ski trails in Essex for a decade, you get to read the story in the snow during the early morning hours. Tracks and their trends don’t lie.”

For Reavis, other threats along the Middle Fork Flathead River corridor outweigh those posed by the Granite Moccasin project. He raised the prospect of a wind or snow storm toppling trees into powerlines and sparking a stand-replacing fire as one reason to support the project, and said the network of infrastructure that allows BNSF Railway to transport oil, freight and passenger trains along the Wild and Scenic River corridor is a more significant culprit contributing to habitat fragmentation than logging roads.

“If you’re against this logging project on the basis of habitat fragmentation and migration corridor for wild animals, think about the ever-growing commerce on the HWY 2 corridor,” Reavis said. “Think about the 2-mile-long trains constantly moving through the landscape. That my friends, is the true culprit of fragmentation in this otherwise gorgeous landscape.”