As Montana’s Grizzly Population Grows, Bear Managers Grapple with Conflict Conundrum

A bear relocated for killing sheep was shot and killed weeks later after charging a Swan Valley landowner, raising more questions about the conflict-response criteria for a population of grizzlies that wildlife managers say has met its recovery goals

By Tristan Scott

When a Swan Valley landowner shot a grizzly bear on June 4 after it threatened his livestock and charged him on his property near Condon, he had no way of knowing that wildlife managers captured the same bear weeks earlier for killing sheep near Potomac, about an hour away. That’s set to change under new legislation requiring the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) to notify county officials within 24 hours of relocating a grizzly bear, and to publish those details publicly to an online dashboard.

The implementation of the new law occurs as FWP expands its inventory of more than 400 approved grizzly relocation sites in Montana. It also coincides with a spate of recent self-defense shootings involving people and bears, shedding new light on the criteria state and federal wildlife managers employ when evaluating whether to relocate problem bears. And because the policies are evolving on a landscape that supports a population of grizzlies federally protected under the Endangered Species Act, it’s all governed by a complicated jurisdictional matrix that prescribes competing state and federal management protocol and recovery plans.

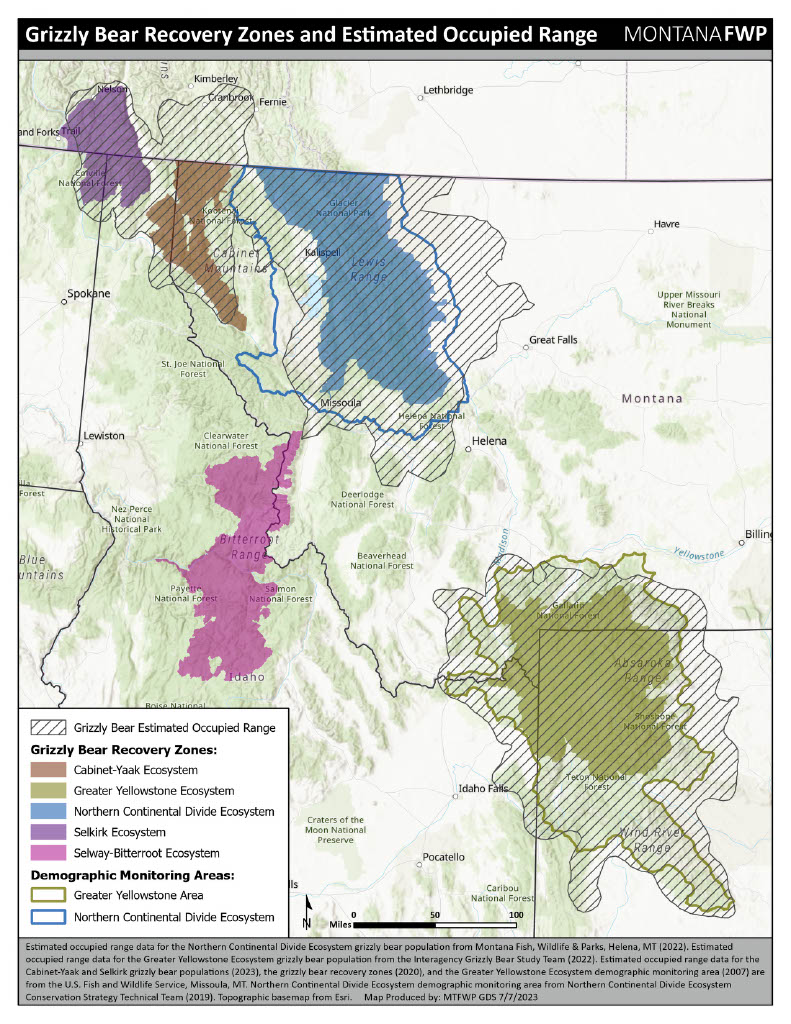

Since grizzly bears are listed as threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), the federal agency has final authority to approve all relocations and lethal removals, as well as to conduct investigations. But FWP is responsible for responding to conflict calls and determining a bear’s eligibility for relocation, and it is beholden to rules adopted by the Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission, as well as laws enacted by the Montana Legislature. Those statutes include Senate Bill 337, which lawmakers passed in 2021 requiring FWP to have all grizzly bear release sites pre-approved by the Commission. The law also prohibits FWP from relocating a conflict grizzly bear captured outside of a designated recovery zone, even as it recognizes that FWS still has the ultimate authority to relocate conflict bears inside or outside of the recovery zones.

In the recent case involving the dead bear in the Swan Valley, for example, state officials in mid-May captured the 2-year-old male grizzly after it was killing sheep on private land just outside of the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem’s designated recovery zone boundaries. Although FWP officials said the state does not typically relocate grizzly bears that have killed livestock, in this case the agency determined the bear should get a second chance.

FWP equipped the sheep-killing grizzly with a radio collar and recommended that FWS release it at a state-approved relocation site in a remote drainage of the Mission Mountains north of Seeley Lake. Roughly two weeks later, the bear was killed after it threatened livestock and charged the Condon-area landowner.

Following the incident, FWP Director Christy Clark, who previously headed the Montana Department of Agriculture and brings a livestock-production perspective to the wildlife management agency she now oversees, said multiple factors have prompted FWP to reconsider its philosophy when it comes to grizzly bear management, including its policy of relocating conflict bears.

“As the grizzly bear species continues to grow and expand, FWP’s long historied relocation efforts become less and less fitting to the circumstance on the ground,” Clark said in a statement to the Beacon. “More than ever, this once routine tool of relocating conflict bears is becoming an ineffective management response.”

In a separate incident that occurred one week later, more than 250 miles northeast of the Swan Valley, another landowner shot and killed a grizzly bear outside his residence in the Bear Paw Mountains, an island range that rises out of the prairie south of Havre. It was the fourth self-defense case involving a dead grizzly bear in Montana in two months, with “defense of life” mortalities representing half of all documented grizzly bear deaths in Montana so far this year.

The male grizzly bear in the incident near the Bear Paw Mountains didn’t have a recorded history of conflict and hadn’t been relocated; indeed, it marked the region’s first documented death of a grizzly bear at the hands of a landowner in a part of the state where sightings are extremely unusual. But the spate of self-defense shootings illustrates a broader point that livestock producers and other conflict-prone stakeholders have been raising for years — as the grizzly bear population grows and expands beyond the contours of designated recovery zones, there’s going to be more conflict on the landscape, and less tolerance for non-lethal management actions such as relocation.

Even so, on June 19, FWP asked the Fish and Wildlife Commission to approve additions to its list of approved grizzly bear relocation sites, a move that Clark said was aimed at giving the agency more flexibility in determining appropriate sites for conflict bears, not because it intends to increase its relocations.

“Like lethal removal, relocation is now and has long been an option available for potential implementation, if circumstances warrant,” Clark said. “Increased number of relocation sites does not necessarily speak to more or less relocations. It does however represent more sites to consider if relocation is the selected management response.”

During his June 19 presentation to the Fish and Wildlife Commission, FWP Wildlife Administrator Ken McDonald said “typically if we have a bear that is involved in a livestock depredation we don’t relocate it.”

“Fish and Wildlife Service has that option but we typically don’t, and if they get a food reward they are less likely to be relocated than if they hadn’t gotten into that kind of trouble,” McDonald said, describing the division of labor between the two agencies as fairly even, with relocations concentrated in FWP’s Region 1, which encompasses northwest Montana. Since 2009, 84% of grizzly bear relocations have been in Region 1, with 72% occurring in Flathead County.

According to McDonald, there were nine grizzly bear relocations across the state in 2023 — four by FWS and five by FWP — while 2024 saw 29 grizzly bear relocations, including 13 by FWS and 16 by FWP, “mostly in Region 1 where we have the highest density of bears and the greatest potential for relocation.”

After removing one of the relocation sites from the agency’s request due to its proximity to a private landowner, the Montana Wildlife Commission approved the agency’s request for additional site relocations. The full list of more than 400 approved relocation sites expires at the end of next year’s bear-conflict season and will need reauthorization.

For Trina Jo Bradley, a cattle rancher on the Rocky Mountain Front near Valier who served on former Gov. Steve Bullock’s Grizzly Bear Advisory Council in 2020, any bear caught killing livestock should be lethally removed from the population.

“They give too many grizzly bears too many chances,” Bradley said. “They keep getting into trouble, they keep getting into calving pastures and grain bins, and they keep passing along that learned behavior to their cubs.”

As chair of the Montana Stock Growers Association’s (MSGA) Endangered Species Subcommittee, as well as the Montana Conflict Reduction Consortium, Bradley led the charge in 2021 to adopt an official policy recommending “lethal removal of grizzly bears suspected or known to have killed a person or livestock after the first offense.” She also opposed adding “any new relocation sites for conflict grizzly bears anywhere in Montana.”

Despite her concerns surrounding grizzly bear management, Bradley credits FWP for “coming a long way in the last 10 years toward understanding that landowners and livestock producers are an important part of the landscape.”

In the roughly six months since Montana finalized its plan for managing grizzly bears, establishing a blueprint for how it will resolve conflicts between bears and people in preparation for the eventual delisting of the species, Bradley said FWP has demonstrated an increasing degree of sympathy toward landowners, attributing the tonal shift to Clark’s arrival at the helm of an agency that has historically placed the onus of conflict-mitigation on the landowner.

“It definitely helps to have her in office because she’s had a ranch and she lives where the bears live,” Bradley said, referring to Clark.

That change in attitude was evident on May 21, for example, when FWP announced that two mushroom hunters had shot and killed a female grizzly bear north of Choteau after the sow reportedly charged them at close range. The press release included a quote from Clark, who personally spoke to both men by telephone immediately after the incident, referring to them on a first-name basis in her statement.

“I spoke to John and Justin shortly after the incident and they were both still shook up,” Clark stated. “They told me their story and it was clear it was very traumatic. What’s important here is they’re ok.”

The press release included a photo of the men on a cell phone, apparently speaking to Clark, as well as a caption that read: “Hours after their harrowing experience, John and Justin share their story with Director Christy Clark via phone.”

Bradley said it’s a welcome departure for ranchers and farmers who for too long have felt responsible for justifying their use of lethal force against grizzly bears, even as the presence of working lands enriches the landscape, including grizzly bear habitat.

“Working lands like ranches and farms provide important habitat for grizzly bears in the western part of the state,” Bradley said. “They live here because our land is healthy and it keeps the ecosystem intact, and it allows them to disperse further east. We are not the enemy. We’re not just out here shooting bears at random because we want to. We are doing the best we can, and sometimes we have to defend ourselves or our livestock or crops or whatever. Most of us don’t hate grizzly bears; we just want them to be managed in a way that distinguishes between good grizzly bears and bad grizzly bears.”

Grizzly bear advocates, however, say drawing that distinction is complicated, insisting that not every conflict involving a grizzly bear invading a grain bin or harassing livestock should result in its death.

Chris Servheen, who retired in 2016 after working as the FWS grizzly bear recovery coordinator for 35 years, acknowledged that the NCDE population has met the recovery goals he helped write. But as livestock predation and other conflicts with humans increase, so have grizzly mortalities, and management strategies need to evolve in a way that strikes a balance between conflict mitigation and conservation objectives. The state’s current management plan, he said, fails to achieve that.

“The bears live in a mine field of humans and human activities. They’re not out there looking for humans; they run across us and our attractants,” Servheen said. “We are very much a risk for bears, which is why we try to provide opportunities for bears to succeed, because we live in such a risky and human-filled environment.”

FWP relocates grizzly bears for a variety of reasons. In some areas, like the Cabinet-Yaak Ecosystem in northwest Montana, bears are relocated from the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem to help supplement the population. Bears can be relocated in response to conflict. They can also be relocated preemptively if the potential for conflict is high. Since grizzly bears are listed as threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, that agency has final authority to approve all relocations and lethal removals.

For decades, wildlife managers have followed relocation criteria detailed in the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) guidelines for conflict responses, which includes preemptive moves and also allows for the capture and relocation of grizzly bears to pre-approved release sites to prevent potential conflict, even those with a conflict history, albeit on a case-by-case basis. That’s what happened in the case of the Condon-area landowner who shot and killed the grizzly bear earlier this month.

But Servheen rejected the notion that the bear’s relocation represented the root of the problem.

“The guy in Condon getting charged by a bear has nothing to do with the relocation,” Servheen said. “Relocated bears don’t get into trouble because they’re relocated, they get into trouble because of what happened beforehand.”

The details of what happened beforehand aren’t entirely clear in the case of the Condon bear, however, nor are those of what happened afterward. That’s due in part to FWP’s tendency of only releasing scant details about a grizzly bear mortality, which Servheen called a missed opportunity for public education and outreach.

“The details of these self-defense killings in particular could be educational for the public,” Servheen said. “It help us learn so much about what happened. Was someone hiking into wind? Were they in thick brush? Did they see any tracks? By understanding what happened we can all learn from that and prevent things from happening in the future. Every one of these self-defense killings is a learning opportunity and not publishing the details of what happened is irresponsible, because it’s going to happen again and again.”

Asked about its policy of not disclosing the details of a self-defense killing, FWP officials deferred to FWS, the agency charged with investigating grizzly mortalities. Likewise, FWS declined to elaborate on the details of open investigations.

“We work with states, tribes, federal agencies, and the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee to provide consistent messaging on living and recreating in bear country,” according to a statement from Billy Stull, a senior special agent with FWS. Investigations undertaken by FWS into the “unpermitted and illegal take of grizzly bears” are all handled similarly, including self-defense killings, Stull said. The U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Attorney’s Office determines the prosecutions for each case.

Currently, management authority over grizzly bears rests with FWS because grizzly bears are a federally protected species. But Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte has advocated for a return of the species to state management, with FWP last fall completing its state grizzly bear management plan. Under the plan, “FWP would continue to ensure their long-term presence in Montana, recognizing that they are among the most difficult species to have in our midst.”

“FWP views grizzly bears as both ‘conservation-reliant’ — meaning the threats grizzly bears face can never be eliminated, only managed — and ‘conflict prone’ and embraces the challenges of ensuring the species’ healthy future, while ensuring the safety of people and their property,” according to the 326-page management plan’s executive summary.

As more bears and more people converge on a conflict-prone 21st century landscape, striking that balance amid intensifying development pressure has grown more challenging, and elected leaders in Montana are ramping up pressure on FWS to delist the species.

“It’s time for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to catch up with the science, follow the law, and return management of grizzlies to the states, where it belongs,” Gianforte said earlier this year after FWS rejected petitions by state governments in Montana and Wyoming to delist grizzly bears in their respective recovery zones — the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem (NCDE) and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) — moving instead to establish a single distinct population segment encompassing grizzly habitat in both states, as well as in Idaho and Washington.

U.S. Sen. Steve Daines, R-Montana, released a similar statement accusing the federal agency of “moving the goalposts on recovery” and promising to “push back every step of the way.”

The leading cause of grizzly death is management removals by state wildlife agencies in response to cattle depredations and bears getting into human foods and attractants. Historically, relocation has been a reliable strategy for maintaining a viable recovery population of grizzly bears while also resolving conflicts.

As grizzlies spread out in search of food and expand their range eastward, as well as to the southwest, they’re appearing on landscapes where they were uncommon a decade or two ago. Over the past few decades, grizzlies in the NCDE have lived mostly in a recovery zone that is 85% public land and includes Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. But that has changed in recent years as grizzlies disperse and their population edges into new territory. The area occupied by grizzly bears in the NCDE has increased by 42% since 2004, and by 25% since 2010, according to FWP.

Kristen Kipp, a rancher and member of the Blackfeet Nation, where agriculture far outstrips other sectors as the leading economic driver, said grizzly depredation can account for up to a 15% loss of a reservation rancher’s cattle.

Like Bradley, Kipp served on the governor’s grizzly bear advisory council five years ago, and is an advocate of non-lethal measures to deter bears, including bear-resistant infrastructure like electric fencing, as well as bear spray and livestock guardian dogs.

“I love electric fencing,” she said. “But a fence isn’t always going to stop a bear. And I love my dogs. I raised Karelian bear dogs for years. But I still don’t leave the house without two forms of protection; either a firearm and a dog, or bear spray and a dog. But on the east side, bear spray isn’t effective when the wind is blowing.”

Despite having gone, in her words, “above and beyond” what could reasonably be expected of landowners to bear-proof their properties, Kipp said landowners still “get shamed for putting the bottom dollar over valuing wildlife or the ecosystem.”

“I think there’s value in both,” Kipp said. “It’s not one or the other. Grizzlies are such a contentious subject, and there’s so much disagreement on both ends of the spectrum. But at the heart of it, landowners do value wildlife and the environment, they just need to make a living and care for the land. They have their own livestock and families to feed, and they don’t want to go under.”

Other landowners have given FWP plaudits through the years, praising the agency’s bear-conflict experts for helping transform rural outposts into bear-smart communities through education and outreach, and for relocating bears to appropriate environments, such as along the North Fork Flathead River.

“I have lived for 30 years in the North Fork area of the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem. Over the years we have been the recipient of many relocated bears,” Elizabeth Holycross, of Polebridge, told the Fish and Wildlife Commission in support of FWP’s list of approved relocation sites. “Overwhelmingly, they thrive up here and I urge you to retain all designated relocation sites in this recovery zone. They are all needed. The North Fork population density is extremely low and we are well accustomed to living in prime bear habitat.”

According to Clark, FWP’s director, “both tools, relocation and lethal removal, are in our management tool box.”

“What stands to change,” she continued, “is how much those two tools are used. Our policies must remain flexible as the landscape changes. More grizzly bears in areas that are fully recovered will continue to influence how frequently FWP relocates grizzly bears. Bear abundance, the impact of lethal removal on that abundance, and conflict history have been and remain among the factors considered as part of FWP’s conflict response process. As those and other situational variables change, FWP will continue to adaptively work towards a conflict response that is effective relative to conflict resolution and consistent with Montana’s established commitment to eventual state management.”

For Clark’s part, she said the agency’s tonal shift since being tabbed as FWP’s director last December is a feature of her leadership, not a bug.

“We want to make sure we recognize the traumatic nature of these events on the people who are involved. Our top concern is human safety and well-being and we want to make sure we’re communicating that,” Clark said. “This year there are more bears and more conflicts and with me being a new director it’s going to sound different.”