The Costly Quest to Save Smith Lake

Facing a $23.4 million price tag for a recreation easement that would preclude private development and preserve public access on 600 acres of Montana school trust land at the head of Whitefish Lake, local stakeholders are left wondering: What’s it worth to save Smith Lake?

By Tristan Scott

Last November, Heidi Van Everen could look toward Smith Lake north of Whitefish and watch the stars align above her organization’s flagship project to conserve 600 acres of some of the most sought-after land in the Flathead Valley. Pegging its value at $7.2 million, the state of Montana’s initial appraisal of the parcel guarding the head of Whitefish Lake was just within reach for Whitefish Legacy Partners, the local nonprofit organization Van Everen has led since 2010, racking up community-wide conservation and recreation wins stretching from Beaver Lakes to Haskill Basin while generating millions in revenue for Montana’s school trust.

Anyone who hikes, bikes, walks their dog, or picks berries in the woods around Whitefish is likely doing so on land that Whitefish Legacy Partners (WLP) has helped conserve, and on a 47-mile network of trails it’s helped develop. For the past eight years, Van Everen and her team at WLP have trained their focus on the conservation of Smith Lake, which is cradled between high-end residential development on Whitefish Lake and the steep, forested slopes of the Whitefish Range. With flat benches and unobscured views, Smith Lake offers some of the highest development potential of any state school trust land around.

It’s also the crown jewel in WLP’s mission to “close the loop” on a decades-old vision that laces together a recreation corridor of single-track trails circumambulating Whitefish Lake and Big Mountain while conserving 13,000 acres of state trust land.

Even though WLP has been laying the groundwork for the deal for nearly a decade, the organization, as well as the state administrators in charge of maximizing the land’s value, have faced a range of challenges through the years, including the effects of the pandemic, an extreme windstorm that in 2020 toppled hundreds of trees in the project area, and administrative shifts at the state and federal levels. But following last fall’s appraisal, and with a letter of support from the city of Whitefish in hand, Van Everen was growing more confident that WLP was poised to deliver another success for the community.

“We were ready to take action and close,” Van Everen said.

Having realized the benefits of past collaborations with WLP and the city of Whitefish, state administrators with the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC) were gaining confidence, too. In the past 20 years, WLP’s projects have generated more than $12 million to Montana school trusts.

It’s what Shawn Thomas, the DNRC’s forestry and trust land division administrator, likes to call a “win-win.”

“The recreational use easements really are a win-win,” Thomas said last week. “These are opportunities to provide long-term assurance to the community and public that this is going to be a place they can recreate moving forward in perpetuity even as we manage our forests to withstand fire and fulfill our obligation to the school trust. I have always viewed the Whitefish Trail as a win-win.”

But three months after the state’s initial appraisal seemed to set the stage for another community-driven conservation success story, DNRC administrators delivered some unsettling news. A problem with the appraisal report on Smith Lake had required them to conduct a re-appraisal, dividing the Montana School Trust Land into four smaller parcels, and thereby inflating the value to a cost of $24.3 million.

For Van Everen and WLP, as well as the donors and the community of stakeholders that had coalesced around the Smith Lake conservation campaign, the stars quickly fell out of alignment; indeed, the sky seemed to crash down on the community’s eight-year quest to save Smith Lake.

“We did all we could to negotiate a fair and reasonable price with the state,” Van Everen said last week, explaining that, short of raising an additional $18 million, the new price tag had forced WLP to consider alternative options that she described as “watered down.”

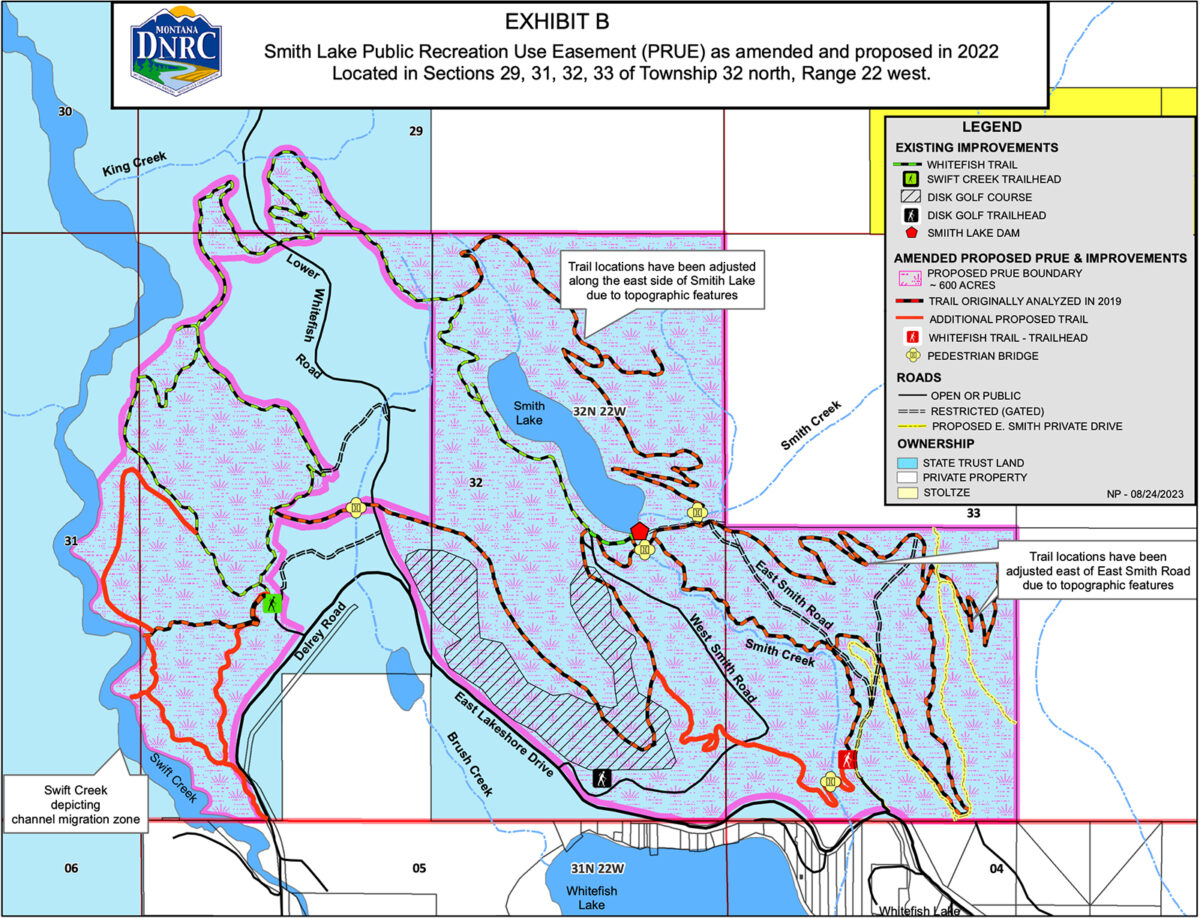

The city originally submitted a proposal for the project in March 2017 seeking to purchase a 480-acre easement on the land ringing Smith Lake. That easement would have permanently secured the existing trail system between Swift Creek and Smith Lake, while separate 16-foot-wide easements would have allowed the construction of new trail and pedestrian bridges to connect the Swift Creek and North Beaver Lake trailheads. In 2022, the city amended its application to include an additional 120 acres under the same easement, which included the section of trail between Swift Creek and Smith Lake but abandoned the connection to North Beaver. Van Everen said those amendments were proposed to ease public concerns that the addition of new trail would disturb wildlife habitat.

Imagining WLP’s next steps following the recent reappraisal, Van Everen said it would likely involve securing trail conservation easements that help close the loop on the trail system, but don’t preclude development rights beyond the 16-foot wide trail corridor.

Delivering the sobering news to her board members and the roster of donors who had already committed millions to the project in good faith, Van Everen said it was among the most difficult moments in her career.

“It’s a huge blow to stakeholders and donors that were intent to conserve critical wildlife habitat and ensure watershed protection in an area with some of the highest developments potential in the valley,” Van Everen said.

“After so many years, we believed we had another big win for the city of Whitefish, the Whitefish Trail and permanent public access, and Montana schools,” she said, adding that completing the loop trail remains a priority, even if the project is stripped of its conservation value. “We are optimistic that trail connectivity is still a possibility and continue working to close the loop of the Whitefish Trail.”

Montana school trust lands are managed to maximize revenue for public schools and other beneficiaries through a mix of uses, including timber sales, commercial development, real estate, agriculture, and recreation. The state is constitutionally obligated to determine the “highest and best use” of each parcel of state trust land based on factors like location, market conditions and potential revenue generation.

The “highest and best use” can include conservation and recreation easements, as well as land leases, which the Whitefish School Trust Lands Neighborhood Plan formalized as a conservation strategy more than 20 years ago. Adopted by the city of Whitefish, Flathead County and the Montana State Land Board, the DNRC was instrumental in crafting that plan, which acts as a sort of roadmap setting forth creative conservation and recreation strategies for the management of 13,000 acres of Montana State Trust Lands surrounding Whitefish, empowering the community to put together deals locally that meet the state’s trust obligations.

In 2014, for instance, WLP and the city of Whitefish permanently secured over 1,500 acres in the treasured Beaver Lakes area for public recreation and conservation in the form of a Public Recreation Use Easement (PRUE). The project’s $7.3 million cost was funded in large part by philanthropist Michael Goguen, with about $2 million coming from the community and WLP.

By agreeing to a PRUE on Smith Lake, the DNRC would surrender the development rights in perpetuity, maintaining the ability to manage the forest for hazardous fuels mitigation while injecting the interest from the sale of the easement directly into public schools, year after year. The four beneficiaries of the PRUE would be the School for Deaf and Blind; Montana State University; Montana State University – Morrill; and the School of Mines.

For the DNRC’s Thomas, the Beaver Lakes PRUE was proof of concept that recreation easements were a valuable tool in the state’s school trust toolbox.

“Ever since adopting the Whitefish School Trust Lands Neighborhood Plan, the idea has been what can we do to monetize the trust at full market value as we are constitutionally mandated to do while still finding conservation values for the community and building recreation opportunities through the trail system,” Thomas said. “Beaver Lakes was the first time we had achieved all those goals.”

Since then, the Beaver Lakes project has continued to produce revenue through interest payments, 95% of which get paid out to trust beneficiaries “year after year,” Thomas said.

“In total, that’s over $3 million so far in interest rates alone,” he said. “It’s been a good deal for the beneficiaries and for the community. And since 2017, we’ve been working hard getting the Smith Lake PRUE going.”

And yet, the going just got a lot tougher for local advocates of the Smith Lake PRUE.

Van Everen understands that land values have increased in recent years, and she said she wasn’t surprised when the DNRC’s initial appraisal of the Smith Lake project assigned a value that matched that of Beaver Lakes, despite Smith Lake’s smaller footprint.

These days, Whitefish is a resort destination, and its ski slopes and golf courses have made it a prime location for second-home development. As property values rose, so has the risk that the state might be forced to sell the property under the same constitutional obligation that requires them to derive the highest best use.

Still, she expected the cost of the Smith Lake PRUE would be somewhat comparable to the Beaver Lakes price tag, and said she certainly did not expect it to multiply exponentially.

Pointing to the success of the Beaver Lakes PRUE, as well as the multitude of other community conservation projects that have emerged out of the Whitefish School Trust Lands Neighborhood Plan, Van Everen said it felt as though the state plucked the football away from WLP just as it was closing in on a field goal.

It’s not just the price tag that’s changed, Van Everen said, but the formula for assessing land, and the conservation strategies formalized in Whitefish’s neighborhood plan for state trust land.

That formula was arrived at more than 20 years ago, and it was reinforced a decade ago, when the city of Whitefish renewed the plan following the success of Beaver Lakes, Whitefish Mayor John Muhlfeld traveled to Helena to present the Montana Board of Land Commissioners, which consists of the state’s five top elected officials, with a 10-year assessment and progress report. A decade later, Muhlfeld said Whitefish has continued to pursue projects that “meet the spirit and intent of the neighborhood plan by providing increased revenue for the beneficiaries of the school trusts while maintaining the economic, environmental, recreational and cultural vitality of Whitefish and the surrounding areas.”

“That hasn’t changed,” Muhlfeld said. “What’s shifted is the administration.”

“We used to have the ear of former Governors Brian Schweitzer and Steve Bullock and their respective land boards who shared in our mutual responsibility to keep these lands working and open to public use and recreation, and now we are seeing the consequences of a fundamental shift in those priorities,” Muhlfeld said. “Now it seems like we’re back to the drawing board. It seems like we’re returning to where we started more than 20 years ago when we first assembled these partners to manage these lands in a way that benefits the trust beneficiaries, preserves public recreation access, allows these parcels to continue to generate revenue as working lands, and precludes development at the head of Whitefish Lake.”

Asked whether the state remains committed to completing the PRUE on Smith Lake, the DNRC’s Thomas said “100 percent yes.”

“We have committed countless hours from staff at our headquarters in Helena who have been working on this project diligently. And we would really like to move this forward,” Thomas said. “I have had a number of conversations with land board members — the land board has actually changed since we started working on this — but what we are trying to do is put a project together for the land board and we are 100 percent committed to it. We would not be spending the time working on it if we were not.”

Thomas said the state was under a fiduciary responsibility to conduct a second appraisal after the initial report contained a discrepancy, with one paragraph describing a range of land values based on different market scenarios, including a high end of $32.7 million if the land was divided into separate parcels. When they ordered the reappraisal, the state modified its appraisal instructions to evaluate the land as four parcels instead of one contiguous parcel.

In the case of Smith Lake, Thomas said it would have amounted to an abdication of duty not to consider the commercial real estate value of the parcels by splitting them into four separate valuations for each of the trust’s beneficiaries.

“We just don’t have any wiggle room on this,” Thomas said. “The trust has to be compensated at full market value.”

To Muhlfeld, the DNRC’s commitment to the project feels disingenuous if it’s now contingent on a speculative price tag that’s so clearly out of reach for Whitefish.

“It’s just shocking that we had an appraisal last fall that assessed those land values in the realm of about $7 million, and now we are well above that,” Muhlfeld said. “We felt that as a city we had a good faith agreement to make sure this deal happened. It’s a critical piece connecting the trail system to the trail around Whitefish Lake and it’s important to our economy.”

Scott Crosby is a certified general real estate appraisal who has conducted appraisals for numerous state and federal agencies, as well as private farm, ranch and commercial property owners, and various private institutions. He was recently hired by WLP to review the state’s appraisal report on the Smith Lake PRUE. His review found that the valuation portion of the report “is considered to be acceptable.”

“Though higher than one would expect,” Crosby wrote that the appraiser provides “support for the values he arrived at in his report.”

“However,” Crosby continued in his review, “the statement of work provided by the State of Montana has him divide and appraise the land into 4 different parcels, even though it is one contiguous parcel, under one ownership, and being encumbered under one easement. By doing this, the State of Montana does cause, whether intentional or not, the values to be inflated. Generally speaking, smaller parcels will sell for a higher dollar per acre compared to larger parcels. By appraising one parcel as four separate parcels, the result is a value that is higher than you would expect to see on the open market. It would have been more appropriate and standard appraisal practice to appraise the parcel as a whole and then provide the contributory values to the whole of each parcel. You would only expect to see four separate parcels being appraised if there were separate PRUEs being placed on each parcel. For example, when appraising a ranch with 10 sections of land for a conservation easement, you do not value each section of land separate or even each entity separate if the landowner has land under different entities. It is all valued as one 10 section parcel. However, this was an assignment condition in the Statement of Work and not an error by [the appraiser.]”

Crosby also reported in his review that the state’s appraisal included a $6 million error, arriving at a before-and-after diminution value of $23,680,000 ($32,680,000 before the PRUE and $8,300,000 after the PRUE). However, Crosby found that based off his calculations and statements he made in his report, the total diminution value should have been $18,253,000 ($32,680,000 – $14,427,000).

Thomas said the DNRC has “always maintained that the value of this project would be dependent on a valid generally certified appraisal” and said WLP and its donors should have understood that condition when they set their fundraising goals. The DNRC did not press its thumb on the appraisal scales to alter its outcome, he said.

“We don’t influence the appraisal. They are what they are and land values are accelerating at a rapid rate, particularly on these large land projects. They are going up at extremely high rates, so there should have been a caveat that the goal would be the actual market value of this land,” Thomas said. “We have been working on this for a very long time and when you’re working on anything that’s tied to land values, time is not on your side.”

Still, Thomas said the DNRC remains “excited to keep working on this” if there’s a willing partner in Whitefish, and is open to exploring alternative options, including trail easements, with WLP and the city.

“I am from the Flathead originally. I recreate on those trails when I go home to visit family. We would love to continue to work on these projects,” he said. “But the reality is that these projects are going to be more expensive and communities need to tie their fundraising goals to pace of land inflation.”

Based on the direction from WLP’s board, even a $6 million math error doesn’t bring Van Everen any closer to securing money toward the PRUE. And while WLP’s application for the PRUE doesn’t expire until next July, she said a hail-mary fundraising blitz is unlikely.

Reid Sabin, chairman of WLP’s board of directors, said the organization is crestfallen, but it is already taking the temperature of its supporters and mapping out the path forward.

“It is a huge disappointment that Smith Lake and Swift Creek will not be the community legacy we had hoped,” Sabin said. “It’s a tough decision to pivot from a permanent solution at the head of Whitefish Lake, but our donors have encouraged us to shift our energies to secure permanent trail easements and seek other conservation and recreation projects that will benefit the community, now and in the future.”

A statement from the city of Whitefish confirmed that it remains “committed to working with our partners to secure permanent trail easements for the Whitefish Trail and ensure trail connections to close the loop.”

“Successful projects are often years in the making, requiring collaboration, constant reevaluation, and persistence to reach a final outcome that is beneficial for all parties,” according to the city. “It is well known that land values in Montana have increased dramatically over the past five years, especially in the Flathead Valley. Unfortunately, these increases are now impacting projects like the Smith Lake Public Recreation Use Easement.”

As the mayor of Whitefish since 2010, Muhlfeld was more blunt.

“These conservation and recreation projects have generated $12 million to the school trust and over $8 million in consumer spending in Whitefish, which is directly related to the Whitefish Trail. The DNRC needs to uphold its commitment articulated in the neighborhood plan. Instead, it’s being short-sighted by simply looking at the value of flipping these properties to the highest bidder rather than creating a long-term revenue stream. It’s critical that we take a much longer view at this from an economic and environmental standpoint.”