On Flathead Lake, Two Women Become One with the Water

Bella Seagrave and Tess Andres swam the length of Flathead Lake this summer, becoming the third and fourth women — and ninth and tenth people — to accomplish the endurance feat in nearly four decades. At 23, Seagrave is the youngest to complete the full crossing.

By Zoë Buhrmaster

As the founder of the Flathead Lake Open Water (FLOW) Swimmers, which promotes open water swimming in the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi, Mark Johnston was thrilled when he received a call inquiring about tips for swimming its length. When he received another inquiry a short while later from a swimmer interested in testing the same endurance waters, his enthusiasm turned to suspicion.

“It was almost like I was confused,” Johnston said. “Is this the same person calling? Because I don’t get calls like that very often.”

It wasn’t. Bella Seagrave, a 23-year-old Missoula-born swimmer, and Tess Andres, a seasoned marathon swimmer from Virginia, both happened to have their sights set on adding the lake to their personal accomplishments this summer. Neither knew of each other.

The first person on record to swim the 28-mile-long lake was Paul Stelter in 1986, with seven others trickling into the record book over the next nearly 40 years.

On July 19, Seagrave swam her way into the records as the youngest person to make the swim. Eight days later, Andres swam the length in 15 hours and 27 minutes.

“Eight people, it took forever, and then two people did it within like, eight days of each other,” Johnston said.

Seagrave has been swimming since she was 6 years old, continuing through high school and eventually into college at Long Island University – Brooklyn in New York. So much so that, now, swimming in a pool on a regular basis is as much a hair care routine as it is exercise, she said.

“I find it’s good for my hair and my skin, which is contradictory to what most people say,” Seagrave said. “I figure I’ve just been swimming for so long my body had to reroute and get used to the chlorine.”

In fall of 2024, a longtime coach and marathon swimmer, Monica Bender, reached out to see if Seagrave would attempt to swim Flathead Lake with her. Seagrave, having graduated earlier that year and missing the structure of a swimming schedule, agreed.

“It just seemed like the natural thing to do to fill that spot,” Seagrave said.

Seagrave put her bachelor’s degree in exercise physiology to use by building her own training regimen, which included being the first one in the pool most mornings at Missoula’s YMCA.

Shortly into her training block, Bender triggered an old shoulder injury, preventing her from finishing enough workouts in time. Instead, she joined Seagrave’s mom, dad, and uncle on the support crew, sharing her knowledge gleaned from past marathon swims, including the demanding 21-mile crossing of the English Channel.

Around the same time, Seagrave also began coaching 8-year-olds for her old club team.

“I’m helping them learn to like swimming and, in the process, reconnecting with why I like swimming,” Seagrave said. “There was a lot of mental training that went into it as well. You can’t just schedule a session in the mental gym.”

A few weeks before the scheduled swim, Seagrave ran the Missoula marathon, for which she’d simultaneously been training.

For the past five summers, Andres has set a personal goal of completing a marathon swim, which she defines as distance greater than 10 kilometers that is not current-assisted, each summer. She landed on Flathead Lake as her focus swim this summer, recalling a “big, pretty lake” from the first time she visited the Flathead Valley about 17 years ago. That time, she had broken her back jumping from a bridge at the end of a float along the Flathead River.

“This was like my comeback tour to Montana and Flathead Lake,” Andres said.

Andres swam in college and quickly fell in love with swimming in open water. As she got older, the theme of her challenges evolved, trending toward going further rather than faster. A science teacher and activity director at a Virgina middle school, Andres said her summers provided the opportunity to take time off and pursue longer trips to explore new places to swim.

She travels with a group of other swimmers, having visited and swam along St. Croix in the Caribbean, North Dakota, Vermont, California, and others.

“It’s a really fun way to kind of see new places and challenge ourselves in new bodies of water,” Andres said.

For Flathead Lake, Andres corralled a couple of swimmer friends as support crew and reached out to a friend in Montana for a boat captain connection. In April, Andres encountered a setback when she broke her elbow, requiring a six-week rest from swimming, which made training “tricky.” When she returned from healing, she resumed training, but limited her swimming to shorter periods and distances than she would normally log while training for a marathon swim.

Later in July, Andres and her friends flew out to Montana, right on schedule.

Seagrave and Andres are the third and fourth women on record to swim the lake’s length, with Seagrave recognized as the youngest at 23-years-old.

The other two women, Sarah Thomas and Emily von Jentzen, both have swimming resumés and records that defy gender. Thomas holds the fastest Flathead Lake crossing ever at 13 hours and 39 minutes, while Von Jentzen remains the only person on record to swim the length of Flathead Lake and back in a single, 56-mile push.

Johnston, whose roots in the open water and ultra-distance swimming world date back to the early 2000s, said that it’s common for women to excel at marathon swimming.

“Especially nowadays in swimming, the ultra-marathon events are tending to be more done and accomplished by women rather than men,” Johnston said.

Numerous studies over the years have found that when it comes to swimming long distances, women are often faster than men. According to studies by exercise researcher Beat Knechtle and others, it’s in part because the female body is better at burning fat over longer distances than the male body. Female bodies typically have around 31% body fat, while males usually have around 19% — and a higher fat percentage equals better buoyancy and insulation against cold water.

To do a marathon race at all requires a lot of work, which is part of why Johnston started FLOW Swimmers — to make information about swimming Flathead Lake more accessible. Hiring or finding a support boat and crew can also be time consuming and fiscally draining. Above all, however, Johnston said the mental challenge of preparing for a long swim is what makes it unique.

“It’s really that the mental challenge of doing anything for 17 hours is to me as hard as doing the swim,” said Johnston. “So that mental aspect of just hanging with anything for that long is what I try to convey to most people.”

When it came time for Seagrave to swim, the weather turned inclement. With limited time off for her and the crew and everything planned for that weekend, Seagrave said she felt it “pretty much had to happen that day,” despite the weather.

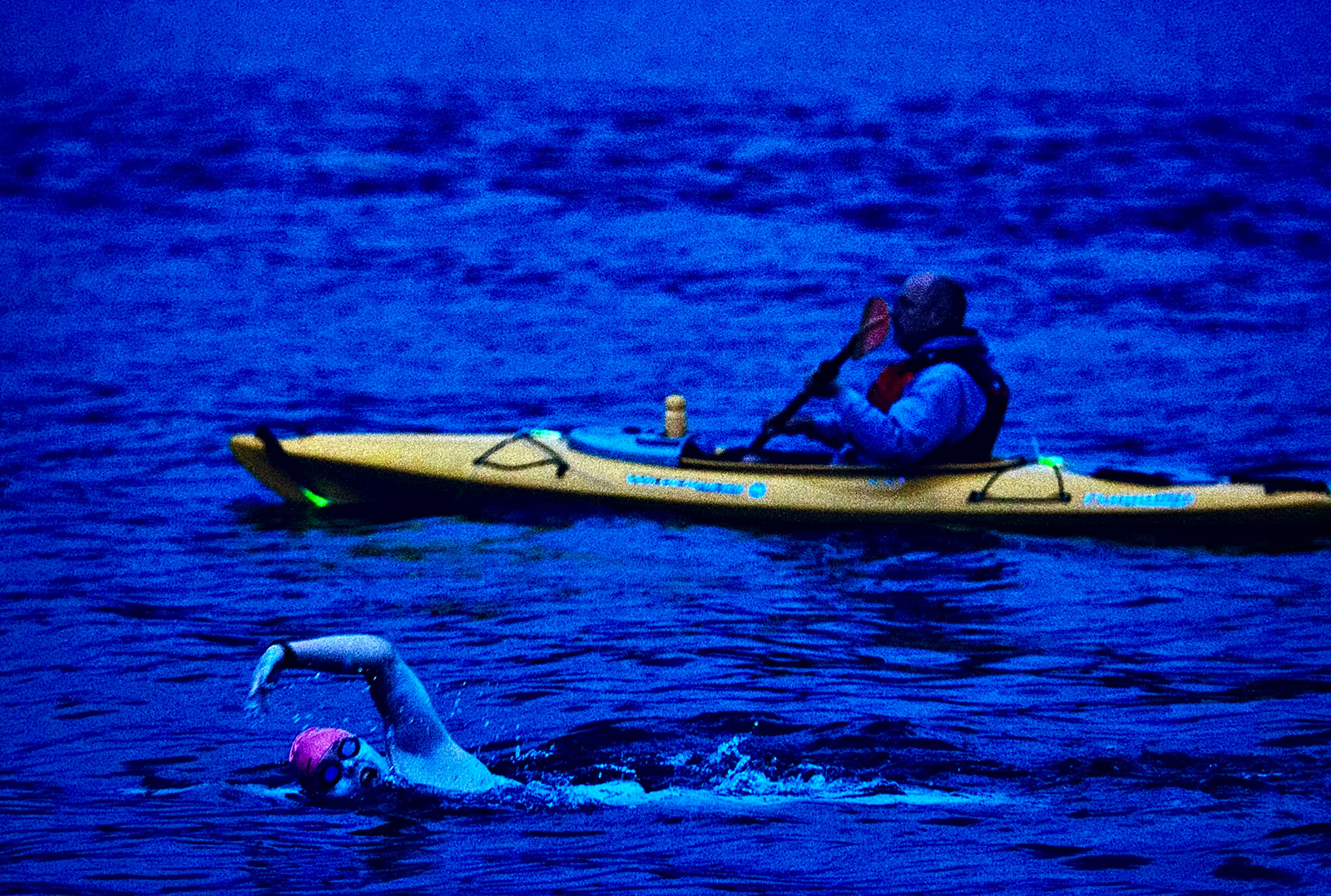

At 11:26 p.m., Seagrave dove into the water at Somers.

The waves were choppy, but bearable. She appreciated starting at night as a practiced pool swimmer, so she couldn’t see what was in the water. Her support team tossed her Swiss Rolls and Smucker’s Uncrustables to help keep her going.

Then somewhere in the middle of her swim, the wind shifted. Seagrave recalled her captain telling her the waves were six to seven feet tall. The large waves made it difficult for her to breathe, while adding distance to her to swim and requiring more energy — with every exertion, the swell would drag her back.

“If I had been swimming against those, I think I would have had to stop,” Seagrave said. “There was no practicing in those waves because I shouldn’t have been swimming in waves like that. But it’s what happened.”

Seagrave said the true mental strain came while in Polson Bay.

At 6:14 a.m. eight days later, Andres jumped in at Somers. Her weather was fortunately better. She tried to avoid looking at mountain peaks that seemed to inch by, relishing the chicken nuggets thrown to her every five or six hours from her support crew.

“I just got out there and you get into a zone and just keep going,” said the seasoned marathon swimmer.

Andres felt nervous about her elbow and told her friend Heather to not share stats from an online tracker until she reached the “Narrows,” a bottleneck feature separating Polson Bay from the northern part of the lake, in case she didn’t make it.

“Then she posted it, and I was like, ‘yay!’ Even though the Narrows to the finish was mentally the hardest part,” Andres said.

Both Andres and Seagrave described encountering the mental challenge of being so close to a finish line that seemed to linger the same distance away despite their steady strokes and relentless forward progress. Their respective support boats waved off the boats whizzing around the busy outlet.

In order to have the swim officially ratified by the Marathon Swimmers Federation, Andres swam without a wetsuit, without touching the boat and without wearing a watch. Seagrave, unconcerned about having her swim ratified, followed the same rules, but made an exception for wearing her watch.

Miscommunication between Seagrave and her support crew led her to believe she had a quarter left of the bay, when she was only a quarter of the way through. Her dad, following beside her in a kayak, began to sink as waves crashed over his boat, filling it with water.

“I can see the shoreline, but it’s not getting any closer, and my dad is sinking behind me,” Seagrave said. “But it worked out.”

After 17 hours and 36 minutes of swimming, Seagrave’s feet touched ground in Polson. As she walked out, her knees buckled, and a woman came out and helped her up.

Supported by good weather and experience, Andres finished at 15 hours and 27 minutes.

“I kind of want to do a redemption swim with good weather,” Seagrave said. “But it’ll have to be in a couple years.”