When he talks about Pat Williams, former Montana Gov. Brian Schweitzer likes to retell a story he heard from Chuck Johnson.

As the story goes, Johnson, a political journalist, attended a forum in the Bitterroot where Williams fielded questions from the public. People stepped up, asked questions and Williams answered in 12-15 seconds, always ending by repeating the same statement: “Montanans demand clean places for hunting, for camping, for fishing.”

The reporter sitting next to Johnson leaned over to him and, as Schweitzer tells it, said, “Is that son of a bitch deaf?”

Johnson replied, “No, he’s going to be a congressman.”

Johnson, himself a storied figure in Montana for a journalism career that spanned five decades before he passed away in 2023, was spot-on. Williams understood access to public lands was a unifying issue for Montanans — but more to come on that later.

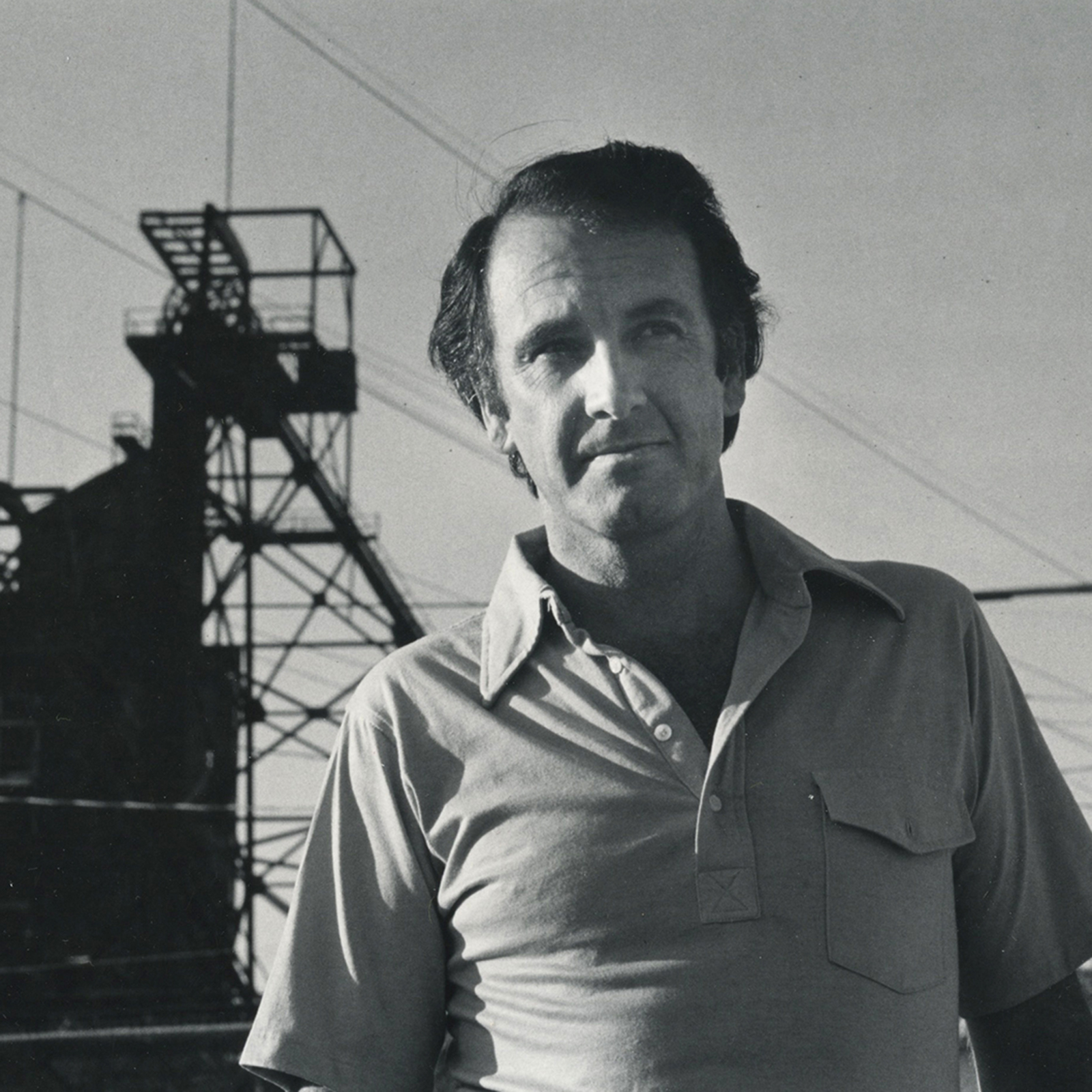

Montanans first elected Williams, a Butte Democrat, to the U.S. House in 1978. He became Montana’s longest-serving congressman. During his time in Congress, Williams was responsible for the passage of the Family and Medical Leave Act; the reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act; and is credited with saving the National Endowment for the Arts, among other legislative achievements. His political career was bookended by what many friends and colleagues described to be Williams’ first passion: teaching.

Williams passed away June 25. He was 87.

His family, friends and admirers say his legacy in northwest Montana lies with his advocacy for conservation and on behalf of Native Americans. But they emphasized Williams didn’t see the challenges of Native Americans, or conservationists, or people with disabilities, or the battle for the arts as different issues. They all connected. The through line was his belief that government could act as a partner to make things better for people.

RUNNING FOR OFFICE

Williams’ early years are well-chronicled: He lived with his Irish grandmother, Elizabeth Keough. He worked at a candy shop. His cousin was Montana daredevil Evel Knievel. He attended the University of Montana, joined the National Guard in Colorado and eventually returned to Butte, becoming a teacher in the mining town.

In Butte, at a Young Democrats meeting, Williams met his wife, then Carol Griffith. Carol and Williams were married in 1965. They welcomed Griff, the oldest of their three children, in 1966, followed by Erin in 1969 and Whitney in 1971. The pair shared a commitment to public service and to teaching, Griff Williams said.

The same year Griff was born, Pat Williams won a seat representing Silver Bow County in Montana’s State House. Pat then cut his teeth working as an executive assistant to U.S. Rep. John Melcher and was a member of the Governor’s Employment and Training Council until 1978.

In 1974, Pat launched a primary election campaign for Montana’s 1st House District against future U.S. Sen. Max Baucus. Baucus bested Pat in the primary and went on to win the general election. But when Baucus stepped away from the House to run for his Senate seat in 1978, Pat put his name in the ring for the Democratic nomination — this time, successfully.

Pat personally knocked on 51,000 doors in western Montana during the 1978 campaign, and he brought the kids in tow. Griff recalled piling into a camper on the back of a pickup truck and traveling across the state as his dad tried to reach voters. He and his sisters would knock doors, lick envelopes and more in the effort to get their dad elected.

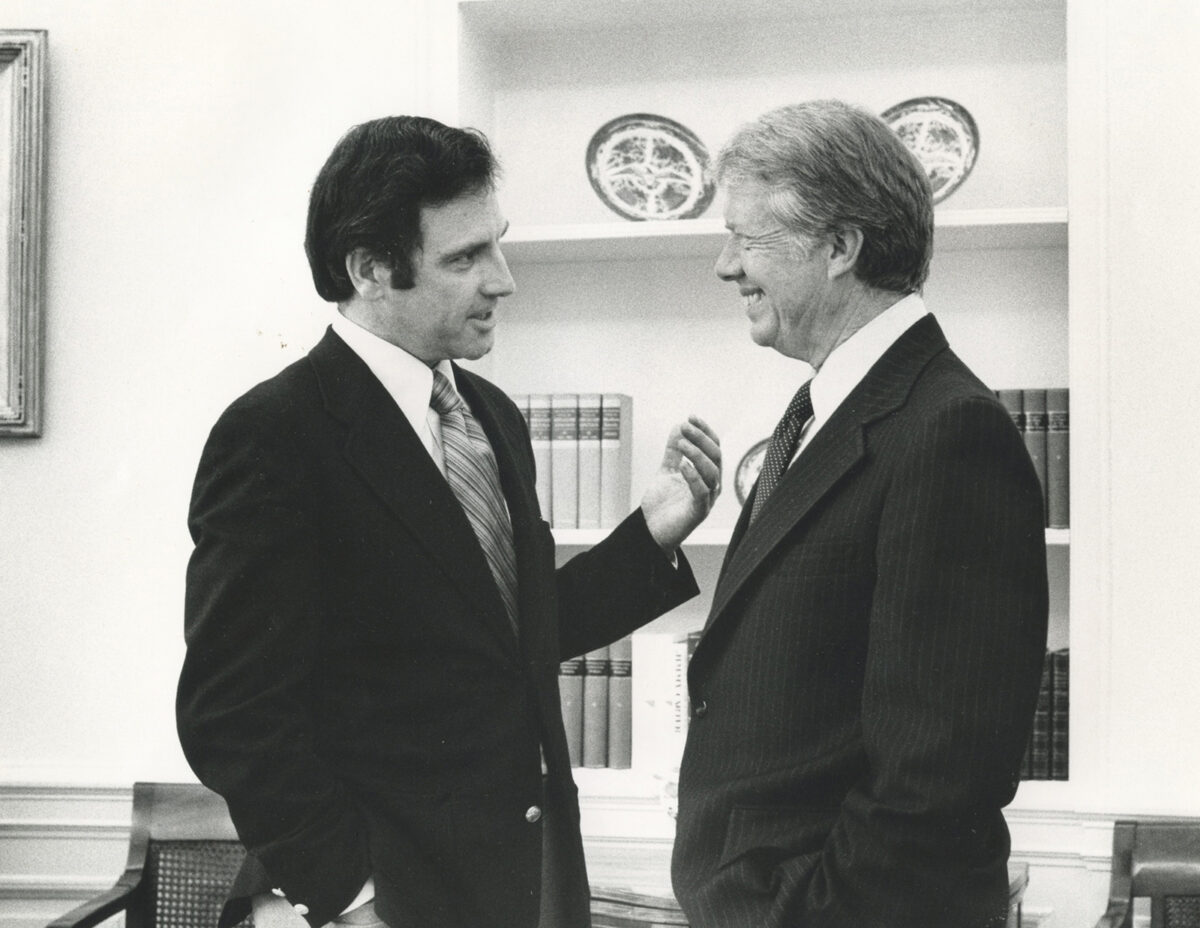

Pat won the 1978 election, prevailing over Republican Jim Waltermire and earning a commanding 57.3% of the vote to take the 1st District seat, representing the state’s western half.

Once Pat won, his family moved to Washington, D.C. But Griff remembers Pat returning to Montana most weekends to meet with constituents in his district.

“You kind of shared your parent with the world at that point,” Griff said. “You know, he’s not just yours.”

For many years, the same person helmed Pat’s campaign machine. Joe Lamson, a University of Michigan grad who moved to Montana in 1974, came onto Pat’s team as his state director in 1983.

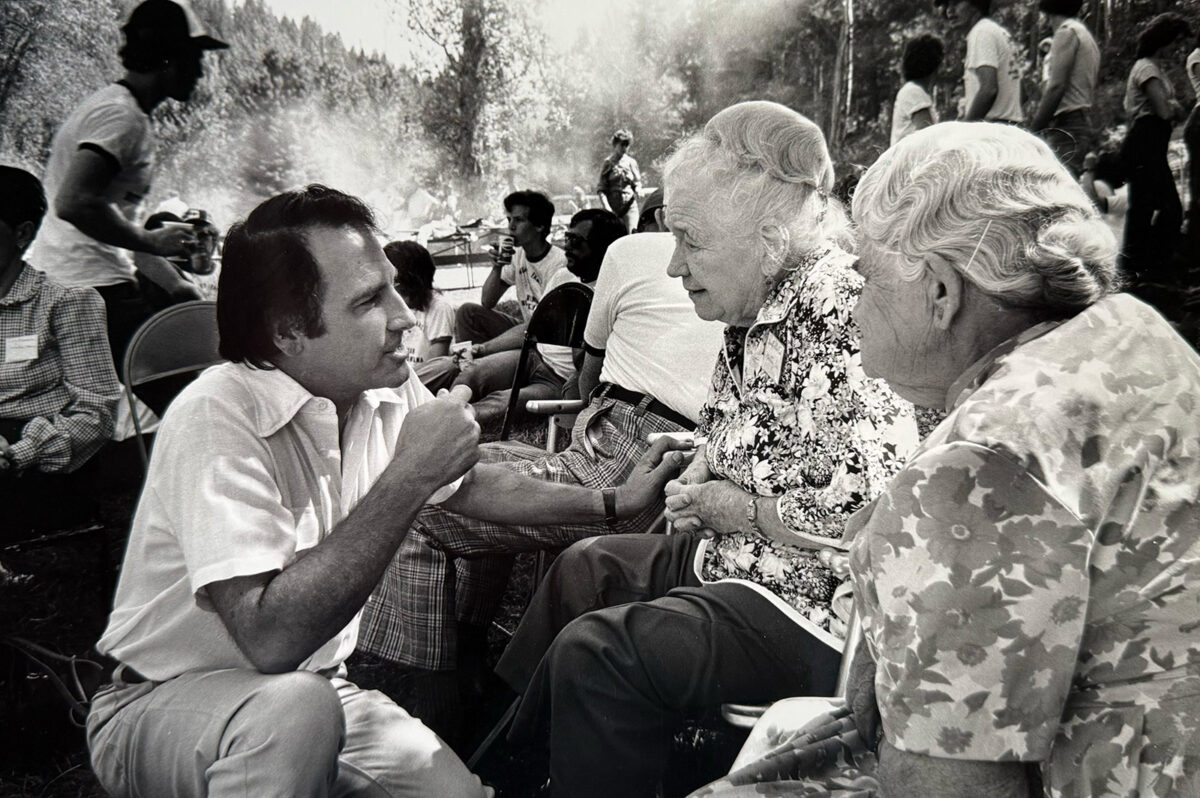

For the next 13 years, Lamson served as Pat’s state director in non-election years and his campaign manager during election years. Lamson said one of Pat’s great strengths as a politician was his ability to connect with people.

“Pat just had this infectious smile and, you know, would take people by the hands and look them in the eyes with that just great look and just, ‘hey pal, how you doing?’” Lamson said. “You were instantly his friend.”

Lamson ran Pat’s campaigns from 1984 through his last one in 1994. But in 1992, a curveball was thrown at Pat and Lamson: Montana lost one of its congressional seats following the 1990 census.

After representing the western half of the state for more than a decade, they were contending with a statewide race. It pitted Pat against Republican Ron Marlenee, who had served as Pat’s counterpart in the eastern half of Montana since 1977.

‘PAT DELIVERED’

The 1992 race was tight, said Celinda Lake, Pat’s pollster at the time. As she conducted polls throughout the race, Pat insisted that Lake include Native Americans. Pat’s insistence on tribal voters’ inclusion contrasted with Marlenee, she said, who had a record of statements considered to be racist.

That year, the Flathead Reservation and Blackfeet Nation entered a challenge to register voters on their reservations. The Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribal council and Blackfeet tribal council passed resolutions promising a buffalo to whoever won the contest for highest voter turnout.

“1992 will truly be the year that Montana discovers the Indian vote,” the resolution read.

Tribal turnout was huge that year, Lake said. Pat won by 14,000 votes, and credited the tribes’ turnout with his winning the race.

Anna Whiting-Sorrell, who worked as the tribal manager for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes while Pat was in Congress, said the tribes supported Pat because Pat was a friend to the tribes.

“You know, in Indian Country, there are a lot of politicians that come and ask for our vote,” she said. “They come every two years, and they still do that, and they come, and they come, and they come, and they ask and they ask. Pat delivered.”

Pat’s relationship with Montana’s Native American tribes kept him in Congress, as opposed to seeking other offices in the state. Lamson said people pushed Pat to run for governor after Democratic Gov. Ted Schwinden was termed out in 1988. People also encouraged Pat to run for the governor’s office in 1992 and 2010.

“In the course of going around the state and visiting the people on whether he should run or not, things like that, he decided to hike to the top of Siyeh Pass,” Lamson said.

Siyeh Pass, located in Glacier National Park, is named for a Blackfeet warrior. The view from the pass looks over the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, and the pass itself lies on traditional aboriginal territory for the Blackfeet.

“… And so, he went up there and he looked at (the land), and he sat there for the longest time looking at it, thinking about it. I said, ‘what you thinking Pat?’ He said, ‘who’s going to take care of our Indian friends?’ It was a big part of his decision, and he felt a real responsibility there to continue what he got started.”

Continuing what he got started meant securing funding for schools on the state’s reservations. On the Flathead reservation, Joe McDonald played a role in that, his son, Tom — now the vice chair of CSKT’s tribal council — remembered. Joe and Pat shared backgrounds as teachers, and Tom said the pair were quick friends. Joe was the founder and president emeritus of Salish Kootenai College.

During the 1970s, Native American students were struggling. The Char-Koosta News reported that in 1973, the dropout rate for Native American high school students was more than twice the state’s high school dropout rate. On the Flathead reservation, 63% of Native American students quit school before receiving their diplomas.

Joe McDonald, along with a slew of other tribal leaders, were appointed to a steering committee tasked with developing an alternative high school on the Flathead Indian Reservation.

Their efforts resulted in the Two Eagle River School, which Pat worked with them to help establish. The school teaches standard subjects but also offers lessons in tribal governance and language. Tom McDonald, Joe’s son, said it allows students to take pride in their tribal roots and has served as a model for other schools to embrace students’ Native American heritage.

“It’s actually incredible to know the number of people that have gone through that system, and that this has supported them,” Tom said. “And the alternative for them would have been something much more negative.”

Pat also sponsored a 1994 bill to provide land-grant status for certain tribal colleges and institutions. That status provides access to federal funding and support for programs in agriculture, tribal economies and more. Montana has seven land-grant institutions — one on each of the state’s reservations. Whiting-Sorrell, CSKT’s former tribal manager, said she thought Pat’s drive to secure that funding came from his understanding of education as an equalizing force.

“He wanted access for tribal people to hear locally, where they were, that education could be built on the foundation of our culture, and our language, and art and who we are as tribal people, which is really pretty landmark for his time,” she said.

Pat and his family’s relationship with the tribes continued after he left office. His wife, Carol, served in the Montana Legislature, including eight years in the Senate from 2004-2012. During that time, she co-sponsored legislation requiring the state to include Native American history as a part of all school curricula.

While Carol served at the state legislature, she and Whiting-Sorrell became close. In 2008, Gov. Schweitzer tapped Whiting-Sorrell to lead the Department of Public Health and Human Services. Carol and Whiting-Sorrell both broke glass ceilings. Whiting-Sorrell was the first Native American to lead a state health department. Carol was the first woman in Montana to serve as a party majority and minority leader in the state legislature.

Whiting-Sorrell remained close with the family for years afterwards, and said that in 2022, Pat’s daughter, Whitney, approached her with an idea.

Whitney wanted to surprise her parents with Indian names from CSKT. Whiting-Sorrell brought that idea to the people that she needed to and then she worked with the Williams family to come up with names for Pat and Carol.

The tribe honored them with the names in 2023. The names capture a person’s innate qualities, and Pat’s name, cikʷsšn, or “Shining Stone,” represented his charisma and the solid foundation he provided for his family and state. The “stone” part held a double meaning. It also reflected his connection to the land and his work on conservation.

CONSERVATION CHAMPION

There’s not a lot that people agree on in politics nowadays. But Schweitzer said if he walked into a bar in the Flathead and asked people who valued public lands, it’d be pretty unanimous.

“When people in the Flathead wonder who was responsible for maximizing wilderness area, and maintaining wilderness area, and public access for rivers and protecting watershed — that was Pat Williams,” Schweitzer said.

A love for the land is baked into Montana’s culture — and it was baked into Pat. Griff said his dad loved northwest Montana, specifically the Mission mountains, Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

During his career in Congress, Pat fought battles for preservation of the Rattlesnake Wilderness, outside of Missoula, and the Lee Metcalf Wilderness in southwest Montana. He also helped pass the 1988 Wilderness Bill, which would have protected around 2 million acres of land as wilderness. President Ronald Reagan pocket-vetoed that bill.

But what conservationists remember Pat for were his efforts to find compromise among all stakeholders when it came to land use.

Tracy Stone-Manning, the president of the Wilderness Society and former director of the Bureau of Land Management under President Joe Biden, said in the 1970s and 1980s, compromise when it came to conservation wasn’t a commonplace approach.

She recalled meeting Pat for the first time at an event in Missoula after finishing grad school at the University of Montana. The first time they met, he told her about how the “false wedge” being driven between industry and conservation could pose issues for conservationists moving forward.

“(Pat) understood that the state had the capacity for both and making the false dichotomy of either/or was dangerous,” Stone-Manning said. “Dangerous politically, truly dangerous culturally.”

Pat applied that belief in practice, too. Michael Jamison, now the executive director of the National Parks Conservation Association, used to work as a journalist for the Missoulian covering the Flathead. In that role, he recalled attending a meeting Pat spoke at.

The meeting’s focus, Jamison said, was the Kootenai-Lolo Accords, a 1990s-era effort to balance wildlife protection and forest job creation. Those accords came on the heels of the “timber wars” of the 1970s and 1980s, which pitted loggers and conservationists against each other as conservationists aimed to protect the northern spotted owl from extinction. The timber wars led to the creation of the Northwest Forest Plan, passed in 1994, which provided a management approach for 24.5 million acres of land on the West Coast. A depletion in the number of available jobs in the timber industry came as a side effect of the plan.

The crowd in attendance at the meeting mostly consisted of environmentalists, Jamison said. They were people likely to be part of Pat’s “base,” and they were advocating for more wilderness and conservation lands.

“Pat said, ‘here’s the deal, folks. The timber wars are over, and you won. And it’s your obligation now to go back out on the field and to take care of the dead and the dying,’” Jamison said. “He’s like, ‘folks are down. You can’t be kicking on them. You need to take care of these people who have been displaced, who have lost jobs, who have been economically dispossessed, who have been there their whole career, their career that they hope for their kid to take over — you got to take care of those people.’”

The point: There needed to be a middle ground.

“It didn’t really matter whether you were industry or conservation,” Jamison said. “At the end of the day, if you were rolling over people, he was going to be there to call your bullshit, bullshit.”

Today, the conservation community prides itself on its collaboration with industry, Stone-Manning said. In both Stone-Manning’s and Jamison’s eyes, that approach is part of Pat’s legacy, though Jamison said it didn’t mean Pat couldn’t play hardball when necessary.

“He knew how to play politics,” Jamison said. “You don’t run that many years in the U.S. House without having some sharp elbows and knowing exactly how to apply them, right? But at the end of the day, you can apply a sharp elbow, and if the guy you applied that elbow to still wants to go have a beer with you, you know you accomplished something.”

BACK TO HIS ROOTS

In 1996, Pat chose not to run for Congress again.

“Carol and I made the decision that it would be ’96, that we would come home and decided to tell you in the manner in which we did,” he said at the time of the decision. “I think the timing of it is okay. My leaving is okay. It’ll be all right.”

For supporters, the decision was a tough blow.

“Well, you know, the thing about Pat was you didn’t want to see him stop,” Tom McDonald said. “You wondered what would happen. I mean, how could you ever find someone that was as wonderful of a man as Pat to fill his shoes? When he was done with representing Montana, that was a supreme loss for Montana, and that was a supreme loss for all of us, but you had to respect his choice.”

Pat retired from Congress in 1997. Many members of Congress, upon retirement, choose to remain in D.C., taking up work as lobbyists. Not Pat.

“Oh my gosh, he loved Montana,” Stone-Manning said. “Deeply, profoundly loved Montana.”

He returned to Montana and to his original profession, teaching courses in the University of Montana’s political science department and serving as a senior fellow and regional policy associate at the Center for the Rocky Mountain West.

Griff and his siblings would sit in on their dad’s classes from time-to-time. Griff described his dad as a “gifted storyteller.” He said it was “illuminating” to listen to Pat talk about current events.

During Pat’s time at the university, Carol, his wife, ran for office. She was the lieutenant governor candidate on the Democratic ticket with Mark O’Keefe in 2000, but they lost to Republican Gov. Judy Martz.

Carol then ran for a seat in the state house, which she won. She served two terms in the Senate following that, from 2004-2012. Whiting-Sorrell said Pat supported his wife in that role, the same way she supported him in his.

Pat sat on several national education-related boards after retiring from Congress. In 2012, Gov. Schweitzer appointed Pat to serve on the Board of Regents, which governs the state’s university system. He came under fire at that time for a statement he made calling some members of the University of Montana’s football team “thugs” when referring to the high-profile Jordan Johnson rape trial. During his hearing for the position, Pat said it was important the Board of Regents take action against students who assault women. The state Senate did not confirm Pat for the Board seat. Johnson was eventually found not guilty of sexual intercourse without consent.

Pat and Carol spent their later years in Missoula. After he died on June 25, Pat laid in state in the Capitol rotunda in Helena on July 2 and July 3. The Williams family hosted a celebration of his life at the University of Montana’s Dennison Theatre on July 15. A recording of that celebration is available online. Speakers included Schweitzer, Stone-Manning, former Gov. Steve Bullock and all three of Pat’s children.

LEAVING A LEGACY

Pat was the last Montana Democrat to hold a seat in the U.S. Congress.

Montana’s federal delegation was split between Democrats and Republicans for years, but since 2020, Montana has become a Republican stronghold. Montana’s last Democratic statewide officeholder, former U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, lost his most recent reelection bid in 2024.

Montana gained back a second congressional seat after the 2020 census. When the state was approving a map for the new congressional districts, an option emerged that placed Lewis and Clark County (Helena) and Park County (Livingston) in the state’s eastern district. Pat told Nonstop Local he was “deeply disappointed” at that option, because no tribal councils in the state agreed with it. That map was approved.

Republican Ryan Zinke now represents the western district Pat used to. Zinke shared a statement on his social media when Pat passed away in June.

“Montana lost an iconic public servant and champion who loved our State and the people he so faithfully served,” Zinke wrote. “His legacy of exceptional leadership shall endure. My prayers and best wishes to Carol and family.”

Both Republican and Democratic state officials shared similar sentiments following Pat’s death.

Pat’s friends, family, supporters and colleagues say his legacy didn’t lie with his party. Instead, they argue it laid with his desire to fight for the good of everybody, regardless of partisan affiliation.

Whiting-Sorrell said, in a time when hate feels normalized, Pat’s memory gives her hope. Lake, his pollster, said he was a “happy warrior” for many important causes. Jamison said his fingerprints remain all over the landscapes he helped preserve in the state. Tom McDonald described him as an optimist.

His son Griff said it was more complex than that. Griff described trying to shield his father from the news in recent years. He said Pat would have viewed it as a personal failure to see politics be as “toxic” as they are today.

Many shared they thought Pat’s approach — which they described as an approach of decency and empathy, even in the face of political battles — is rare in today’s environment.

Still, Griff said Pat tended not to show his anxieties publicly, and he appreciated people remembering Pat as an optimist. Since his father passed away, Griff said he keeps returning to the idea of politics being about “we, not me.”

“I think for Dad, you know, one of the legacies was just this idea of compassion and kindness,” Griff said. “I think he led with that as a kind of motivating guidepost for him. He really wanted to respect people, even ones that disagreed with him, and I saw it firsthand all the time … He truly believed that the things that he was advocating for were going to make the lives of working people better.”