Overdoses Rise in Flathead County, Stretching Local Resources and Leaving Families Reeling

With a record high of overdose-related EMS calls in Flathead County in 2025, grieving family members and recovering addicts cope with loss while drug enforcement officers and treatment experts seek to bring awareness to the valley’s growing opioid crisis

By Zoë Buhrmaster

A teenage boy begging for a dog, Riley McConnell made a pact with his parents. They’d buy him one – Zeus, a large Anatolian Shepherd and Black Mouth Cur mix – if he stayed sober.

That was when Riley was in high school, his mother Evermay Mitchell recalled. It was the first time Riley had stayed sober since he began experimenting with drugs around junior high, starting with “robotripping” from high amounts of cough syrup before turning to drinking, using cocaine, smoking meth and fentanyl.

He stayed sober for about a year and a half.

Despite his parents’ best efforts, Riley returned to a familiar pattern of substance abuse. On June 14, while the rest of his family was away on a weekend trip, Riley hung out with some friends and, after they had gone home, he smoked fentanyl. He died at 20 years old alone in his family’s basement where he lived. The coroner ruled his death an accidental overdose.

After spiking to peak levels in 2023, drug overdose deaths had trended down in the U.S. until last year, when a Centers for Disease Control (CDC) report showed that fatal overdoses had risen again, a reversal that drug and addiction researchers say is troubling.

The trend is also showing up in Montana.

The main driver of overdoses in the U.S. are opioids, a class of drugs that include prescribed pain relievers like oxycodone, morphine, and hydrocodone, and illegal substances like heroin and illicit fentanyl. Because of its potency, 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, and the low cost to make it, fentanyl has become one of the most common synthetic opioids responsible for overdoses around the country, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

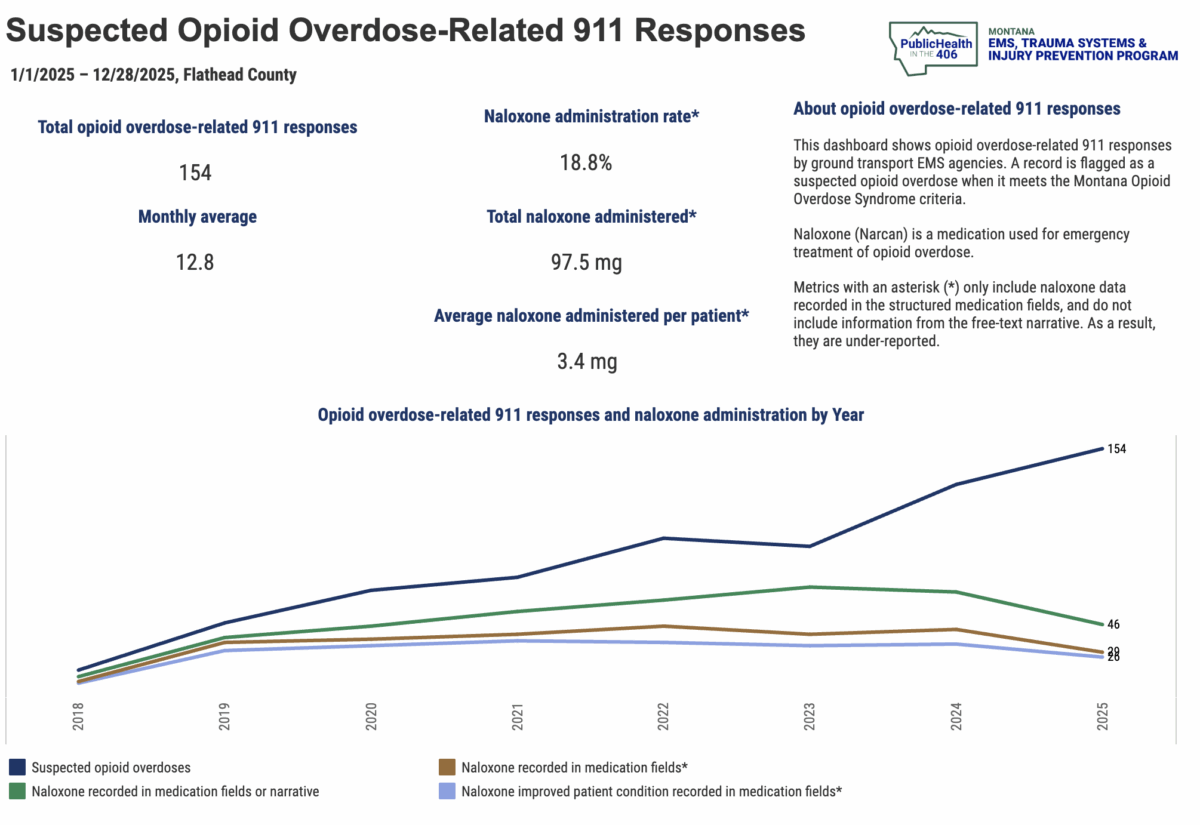

In March 2025, the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services (DPHHS) announced a significant increase in statewide overdoses, with 95 in one month. In May, the department recorded 104 suspected overdoses. While overdose-related calls for Emergency Medical Services (EMS) have gone down slightly in recent months, some counties, including Flathead, have continued to see record-high numbers for overdose-related calls.

This year marked a record high for overdose-related calls in Flathead County, with 154 suspected overdoses as of September, according to the Montana EMS Dashboard. (The dashboard has not been updated since September due to technical issues, according to DPHHS Communications Director Jon Ebelt.)

As a drug intelligence officer for Montana, William Janisch keeps a watchful eye on the state’s drug patterns. His team facilitates collaboration between federal and state agencies and local organizations to share information on drug seizures, overdoses, and other pertinent information to improve drug officers’ ability to report and alert the public to local trends.

The factors playing into rising overdoses are complex, he said.

“People think that a reduction in fentanyl equals a reduction in overdoses,” Janisch said. “That’s not the case, because no one knows how much fentanyl is in each pill to cause those overdoses.”

Statewide, he pointed to three major threats in the drug supply chain as likely factors contributing to the growing number of overdoses — poly-substance drug use, or the combined use of two or more substances; a transition from pills to powder; and an increase in carfentanil, a synthetic opioid more powerful than fentanyl.

Across Montana, officials have observed an increased use of more than one drug at the same time, or poly-drug use. In 2021, there were 15 cases of fatal overdoses in which both fentanyl and methamphetamine were found in the user’s system. This year, through the beginning of November, the State Crime Lab had autopsied 40 cases in which both fentanyl and meth were present.

Using multiple drugs at the same time is often a result of mixing to supplement different effects of stimulants, such as meth, with relaxing effects from opioids, like fentanyl. At Oxytocin, an addiction treatment center in the Flathead Valley, a man who had used opioids most of his life until joining the center in May explained that in his experience, using both meth and fentanyl had become common practice.

“It’s just chasing the dragon,” he said. “Everyone who uses kind of mixes it. I don’t really like meth, but I still used it.”

During one of his final encounters with the drugs, the man said he was high on meth and “already jacked up” when he took a hit of something “like a bong” before identifying the drug he was smoking as a strong form of fentanyl. After realizing what he’d done, he immediately began experiencing symptoms of overdose and passed out.

“I was wholly distracted,” he said. “I had the biggest hit of my life and then 15 minutes later I get revived by my friends’ 12-year-old.”

There’s also been a shift in the fentanyl market from pills to powder, “which is considerably stronger,” Alan Brooks said. Brooks is the commander for the Northwest Montana Drug Task Force, a High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) program that works on dismantling drug trafficking organizations and street level interdiction through partnerships with federal, tribal, state and local agencies.

“It also contributes to our overdoses because then on the user end, it’s a lot more potent and how they use it is still a variable, and we have unintended overdoses,” Brooks said about the trend toward powder. “That’s our biggest threat, and that’s what we’re trying to strategically focus on.”

A rise in carfentanil, a form of fentanyl that can be up to 100 times more potent, has also added to the increase in overdoses.

“On the user end, they don’t have the ability to really determine whether that’s present,” Brooks said.

In some cases, however, it has become the drug user’s preference to use carfentanil, especially if the person’s tolerance has risen. Narcan can be used to help reverse a carfentanil overdose, but because the potency of the drug is higher, it’s a higher risk that requires more naloxone — the generic name for the synthetic drug that blocks opioid receptors in users — and therefore loses its effectiveness.

“If you use carfentanil, you’re more likely to overdose,” Janisch said.

While those statewide trends have all been reflected in Flathead County, Brooks said the drug task force has also been finding fentanyl cut with other substances, such as xylazine. Xylazine is a powerful veterinary sedative and can’t be mitigated by Narcan, presenting a “considerable concern,” Brooks said.

“We know when a bad load gets into the valley because we will have a cycle of overdoses,” Brooks said. “Say over a weekend, you’ll have multiples — whether fatal or not — reported and that’s obviously indicative to us of a strong load of fentanyl that has come into the valley.”

Staff at Oxytocin have also encountered more cases in which urinary analysis reveals traces of xylazine mixed in with meth or fentanyl, particularly among patients who are new to treatment, the addiction treatment center’s director, Pamela Liccardi, said.

“If fentanyl is cut with xylazine, Narcan is not effective,” she said. “It’s so fast acting, in and out of the system quickly, that the fact that we have a positive is astounding. But a lot of dealers are cutting their product with xylazine.”

Part of the discrepancy in overdose numbers between Montana and the rest of the country is that, in general, trends often take a while to reach the northern state. The other aspect that Brooks has discussed with colleagues in the drug enforcement world is whether or not the national downward trend will continue.

“We definitely believe there’s a level of underreporting for non-fatal overdoses because of the lack of interaction with first responders,” Brooks continued. “On a regular basis I’ll talk to users and they’ll tell me that they’ve overdosed half a dozen times and been revived by a peer who is administering naloxone and that is never known by a reporting person such as the first responder or EMS.”

For Flathead County, drugs are often trafficked in from larger cities in Washington such as Seattle or Spokane via the Highway 93 corridor or the passenger rail service Amtrak, which in the drug task force world is often referred to as the “Fentanyl Express,” Janisch said.

“It’s a day trip to get them,” he noted.

Brooks also said that though the street prices for drugs in northwest Montana will fluctuate depending on the available supply, it is often a profitable place for larger drug organizations to sell.

“The pricing here is extremely lucrative for these large traffic organizations,” Brooks said. “For instance, a fentanyl pill in Spokane is like 50 cents. In Kalispell, it’s $5 to $10. When it’s taken over the divide to the [Blackfeet] Reservation, it’s worth as much as $40.”

Opiates, however, also enter the drug supply in the Flathead Valley by other means, including through overprescriptions.

For Dr. Jennifer Gemmill, an emergency room doctor at Logan Health, opioids have figured prominently into the substance-use-disorder picture ever since she started practicing 20 years ago. She recalled the way narcotics were prescribed freely in the early 2000s, touted as a kind of “wonder drug.”

“That created a really unfortunate downstream effect of use and has really extended into a number of generations,” Gemmill said. “It’s been something that, for most of us who are practicing, we’ve seen throughout our whole career.”

Overdoses usually present similar symptoms no matter the opioid, Gemmill said. Patients are unresponsive, not breathing well, and their oxygen levels are extremely low. Medical professionals will administer Narcan, potentially multiple doses, to immediately reverse an overdose. Then they’ll try to determine what opioid the patient used to understand how best to continue treating them.

Fentanyl is the most common opioid they’ve seen lately, Gemmill said. It’s additionally concerning, she said, for those who have had addictions to narcotics like hydrocodone and oxycodone for years and run the risk of an overdose by using pills laced with fentanyl, which is notably stronger.

Patients entering the emergency room are often prescribed opioids for pain relief. For many people, it only takes three to four days to become addicted because of the drugs’ strength, Gemmill said.

That’s how Brittany Chumley’s addiction to opioids started, when a doctor prescribed Percocet for her at 15 years old after she sustained an injury from gymnastics. Having other family members with opioid addictions, she eventually tried a range of other drugs, including oxycodone, hydrocodone and morphine. Then in 2015, a doctor in her hometown Libby with a reputation for overprescribing had his license suspended, and suddenly opioids became harder to get. A few years later, her mom passed away.

“I’d never really been much of a meth user, I was always more narcotics,” Chumley said. “But after they were impossible to get, and after mom died, then I started using meth. At the end, for about the last year, I was shooting it.”

“That’s a terror that will never go away, the hallucinations that come with it and even months after,” she continued. “It holds on for a long time.”

With scarce homeless shelters and housing resources in Libby, Chumley wound up at a shelter in Flathead County. She’s been sober since November 2023, and in March 2024 a court order for addiction treatment placed her at Oxytocin. She now has a job and is living in her own apartment while working through treatment. Chumley said she’s grateful for the center’s peer-groups, which provide an opportunity for her to connect with and feel supported by other people going through similar steps to work through their own addictions.

“They’ve been the only one there for me, when nobody else has,” Chumley said.

At the hospital, Gemmill said that prescriptions depend on a patient’s need and a doctor’s assessment. Still, from a prevention standpoint, she thinks that systemwide there would be a benefit to having a stringent standard for prescriptions and better communication with patients about the risks involved.

“I think we need to have more open communication with our patients about what these medications do and why we are limiting the number that we’re prescribing,” Gemmill said.

In addition to increased awareness, there is a need for more resources to help people already struggling with substance use disorders, she said. With all the other priorities in the Flathead Valley, funding for addiction resources has often been limited.

“Having more robust treatment is really necessary, but those types of programs don’t get a lot of funding and certainly out here they’re on the lower end of the priority list, which is really unfortunate,” Gemmill said.

Wellness kiosks are a strategy that Gov. Greg Gianforte took up in 2024, when he announced that the state would invest $400,000 to install 24 of those kiosks throughout the state in response to 2023’s increase in overdoses.

Inside the Flathead City-County Health Department in Kalispell, a wellness kiosk offers naloxone, fentanyl test strips, hygiene items, and other wellness supplies at zero cost to community members. Mandie Fleming, harm reduction manager for the county health department, said that the department has received more people interested in those products.

“Our harm reduction team has been working to increase community awareness about how naloxone works, and who should carry it,” Fleming wrote in an April email to the Beacon. “As a result, we’ve seen more people requesting naloxone and wanting to be prepared in case they witness an overdose. We recommend that anyone who uses opioids or may witness an overdose carry naloxone.”

James Pyke leads the Crisis Assistance Team (CAT), a program born in 2020 to help assist law enforcement in behavioral health calls, which at times includes drug-related calls. Most often, they’re called onto the scene at the request of dispatch or the responding EMS unit on site. Once any medical emergency has been resolved, care coordinators might do an assessment and craft a safety plan, or connect someone with a suspected overdose to immediate resources.

“We’re trying to connect with that individual regularly over the coming days and up to 14 days to get them that help that they need or that they’re willing to accept,” Pyke said. “And probably in the substance use category, the care coordination piece would be the most powerful part of our program.”

Care coordinators will follow up either in person or over the phone, putting those with substance use disorders in touch with relevant resources in the community based on a person’s interest and need. With a release signed by the patient, CAT coordinators can help set up appointments for them at local treatment centers like Oxytocin or others in town for long-term treatment.

Oxytocin has provided outpatient addiction services and mental health services since the clinic’s doors opened in 2019. It’s one of several outpatient treatment centers in the Flathead Valley.

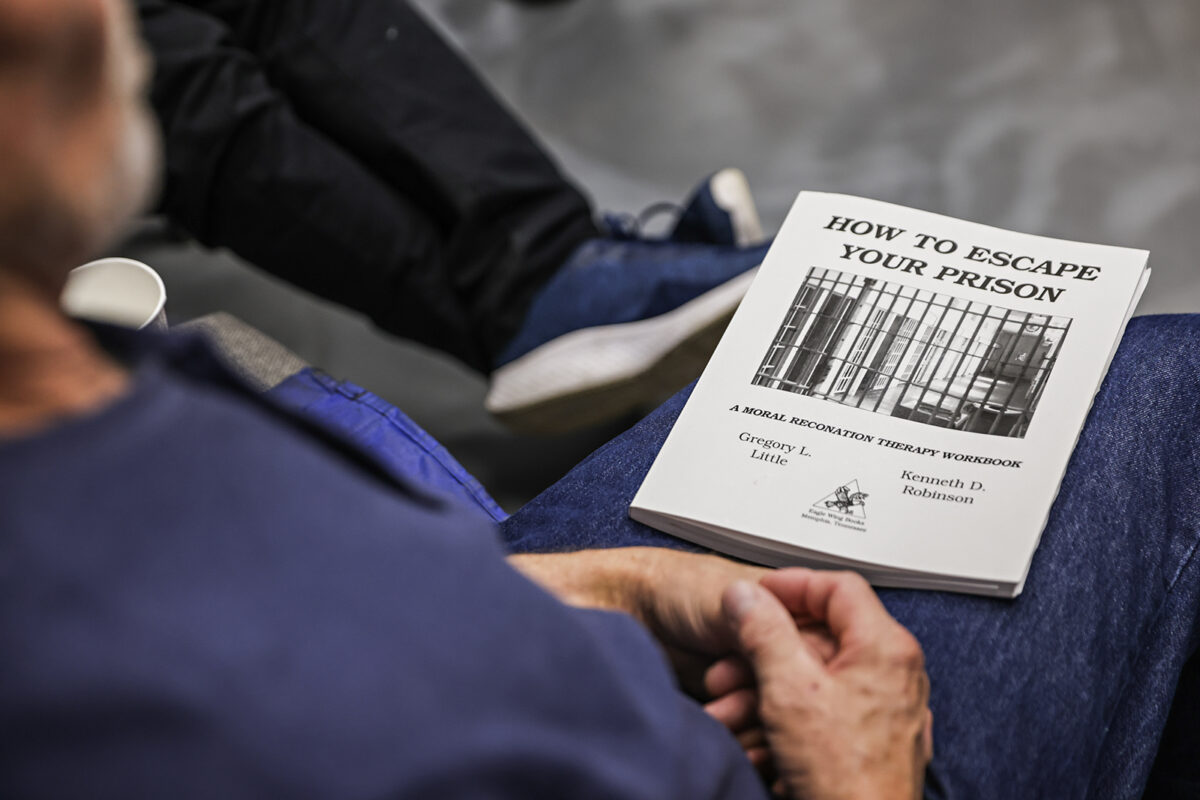

Those that survive an overdose and are connected with resources like Oxytocin — either through CAT, a court-order or self-admittance — undergo an assessment process that informs the treatment plan staff craft for them. While each is designed to a person’s need, all require complete sobriety, per clinic policy.

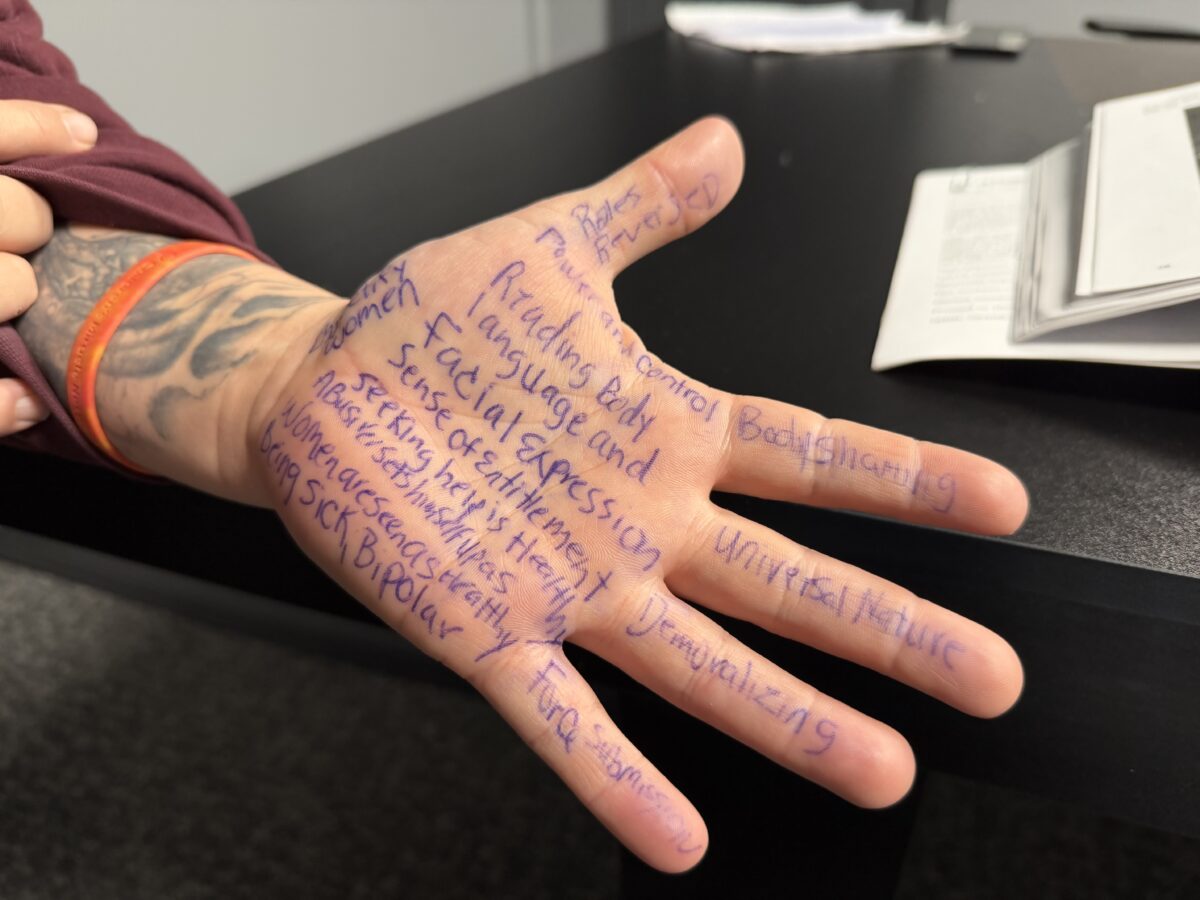

Part of Oxytocin’s goal is to destigmatize addiction by removing the idea of addiction as a reflection of bad morals and teaching the brain the science of how addiction works, Liccardi, the clinic’s director, said.

“When we’re high or drunk, our front lobe is offline — our decision-making center — so we should expect poor decisions, expect impulsivity,” Liccardi said. “It’s rewired to using as the new normal.”

When there’s someone accessing Oxytocin’s services who is overdosing on a frequent basis, Liccardi tries to get them into an inpatient facility in the state, though spaces are often limited, she said. If that fails, staff will keep up with them regularly to help ensure they don’t relapse — a situation that can also lead to an overdose.

“When you’re not using a substance, your tolerance goes down,” she said. “Then we use again, to the tolerance that we’re used to — thus the overdose.”

When he died in June, Riley had been enrolled in drug treatment court for his second felony offense for drug possession.

He would often use between urinalysis testing, leaving enough time in between highs to register as clean by the time he had to test again, his mother, Evermay, said. She called his probation officer and his therapist, begging them to recommend inpatient treatment. Instead, Riley’s lawyer had his sentence reduced to drug court.

“I knew it wasn’t going to happen with him free,” she said, referring to Riley staying sober.

While in drug court, he was allowed to continue living in his family’s basement, with requirements to meet weekly with the same counselor he’d seen since he was 15. He also met monthly with a drug court treatment coordinator in Polson, and regularly attended Narcotics Anonymous meetings.

Riley was charged with his first felony when he was 16. He had been driving when a friend in the passenger seat pulled out a gun and shot at an ex-girlfriend’s house. Later caught by police, Riley confessed to what happened. He was placed on juvenile probation while his friend went to juvenile detention. When the friend got out, he came by Riley’s family’s home and, in the early morning hours, shot at the house. He was arrested and sentenced to 20 years in Montana State Prison with 13 years suspended.

After the incident, Evermay noted that Riley’s behavior changed and his drug use increased. Bullets had gone through his parents’ bedroom, where his mom, stepfather, and little sister normally slept; fortunately, they had been gone that weekend and no one was hurt.

“That really took a toll on Riley, emotionally,” Evermay said.

Whenever Riley did open up, his mother would talk to him about his depression and difficulty sleeping. She’d suggest seeing a doctor who could potentially prescribe a course of antidepressants. But Riley didn’t want to take more pills because he said that he’d be inclined to crush them up and smoke them instead, Evermay recalled.

Before Riley’s drug use increased, he got straight A’s in school, Evermay said. He hung out with family, teasing his little sister Adalyn by gifting her a banana-related object each year for her birthday, an inside joke that he wouldn’t let go. He rode four-wheelers and spent time outdoors with his dog, Zeus.

“It’s just so hard to explain the grief or the pain,” Evermay said. “It’s just indescribable.”

Evermay recalled when she first found tinfoil in Riley’s room, a Google search led her to believe it was for meth. It wasn’t until later when the father of a friend of Riley’s came over and said he knew that both of their sons were using fentanyl.

“I mean really before I knew Riley was doing it, I had never heard of fentanyl,” Evermay said. “My hope is to get more awareness that it is in the valley.”

In addition to investigating drug patterns and supply in the northwest corner of the state, Brooks and his team also work on increasing awareness about substance use disorders and pertinent drug patterns in the state, through public talks at school districts and community organizations.

Last year, the team secured a trailer that simulates a teenager’s room. It’s intended for parents to walk through and point out things indicative of drug use, and after educate them on what they missed. With a current team of five, however, Brooks said it’s difficult to split time between public outreach and other casework or investigations.

“There’s a lot of lack of awareness,” Brooks said. “I can tell you honestly that I wish I had double the resources to be able to do that.”

In the field, he often encounters people who use. In those instances, his strategy is heavy on engagement, light on enforcement.

“A big part of it is just having the conversation and planting the seed that there are alternatives out there,” Brooks said. “But a lot of the times, we’re just having the conversation saying, ‘hey, you’re not alone, you’re not a bad person because you’re stuck in his, and there is hope.’”