‘It’s Not Perfect, But We’re Proud of This Plan’: Agency Specialists Detail Revisions to Wild and Scenic Flathead River Strategy

An "unrestricted, unlimited" permit system would produce key monitoring data to support long-range user-capacity thresholds and management triggers, while restrictions on motorized camping, human waste and fires aim to improve conditions in the near-term. The draft plan is up for public review until March 13.

By Tristan Scott

A half-century after Congress designated the Flathead River system for safeguards under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, staving off plans for dam construction and prohibiting development on its three forks, public resource officials are charting a management strategy they believe will preserve the waterway’s integrity for decades to come.

But with a range of public interests competing for management priority on a system that can only accommodate so much pressure, and with public agencies bounded by logistical and administrative limitations to their ability to manage access, the architects of the plan are seeking public feedback to fine-tune it.

“We’re at a very important milestone,” Rob Davies, the Flathead National Forest’s district ranger overseeing the Hungry Horse and Glacier View districts, said. “We have a draft plan and environmental assessment for public review. We’ve already incorporated a lot of public input into it, and now we’re at a point where we’re trying to refine the new plan and the environmental assessment that supports it. It’s not perfect, but we are proud of this plan and what we have accomplished in terms of trying to find a balance on a very complicated river system.”

As the public weighs in on the draft plan and environmental assessment, both of which are years in the making, planning officials and recreation specialists with the Flathead National Forest are encouraging community input and understanding as they puzzle out and complete the final document.

In interviews with the Beacon and during public meetings this week, agency staff described an adaptive strategy to steer future use of the waterways based on their classification as having wild, scenic or recreation values. The draft plan defines the system’s existing and desired conditions while establishing user-capacity limits designed to prevent those conditions from deteriorating. It also identifies thresholds and triggers for management action, and it implements new restrictions on motorized camping, human waste disposal and campfires.

Perhaps most notably, the plan creates an apparatus to gather more accurate monitoring and river-usage data by implementing an “unlimited, unrestricted” permit system on all three forks. Although the details of the permit system are not final, recreation specialists emphasized that it is not meant to be restrictive; not yet, anyway. Instead, it’s an opportunity to gather real-time data on river usage, as well as provide education and outreach by promoting Leave No Trace guidelines and river etiquette.

“The permit system that we’re proposing with this new plan is unlimited and unrestricted,” Davies said. “We want to make this as easy as possible, so when you’re on the river, we can start getting accurate counts of how many people are actually out there.”

Administrators said they hope to offer the permits for free, which wouldn’t be possible through Recreation.gov, the government’s centralized reservation website that charges users a $1 add-on fee. At Tuesday’s public meeting, some attendees also noted that Recreation.gov can have the unintended consequence of promoting a region to out-of-state markets. The planning team members said they’re exploring alternatives to Recreation.gov.

Even after agency officials issue a final decision for the plan and environmental assessment in May, they’ll be at least one year removed from implementing the unlimited permit system, which would most likely launch in June 2027.

In the meantime, the public has an opportunity to shape the plan by providing feedback through March 13.

“It’s going to take some time,” Davies said. “And when we do implement the permit system, our strategy is going to be education first. We’re not all about, like, ‘Oh, where’s your permit?’ Compliance and enforcement will come later if necessary. We just want to gather information and educate everyone on the changes, make sure they’re clear about what the new plan requires and some of the new regulations.”

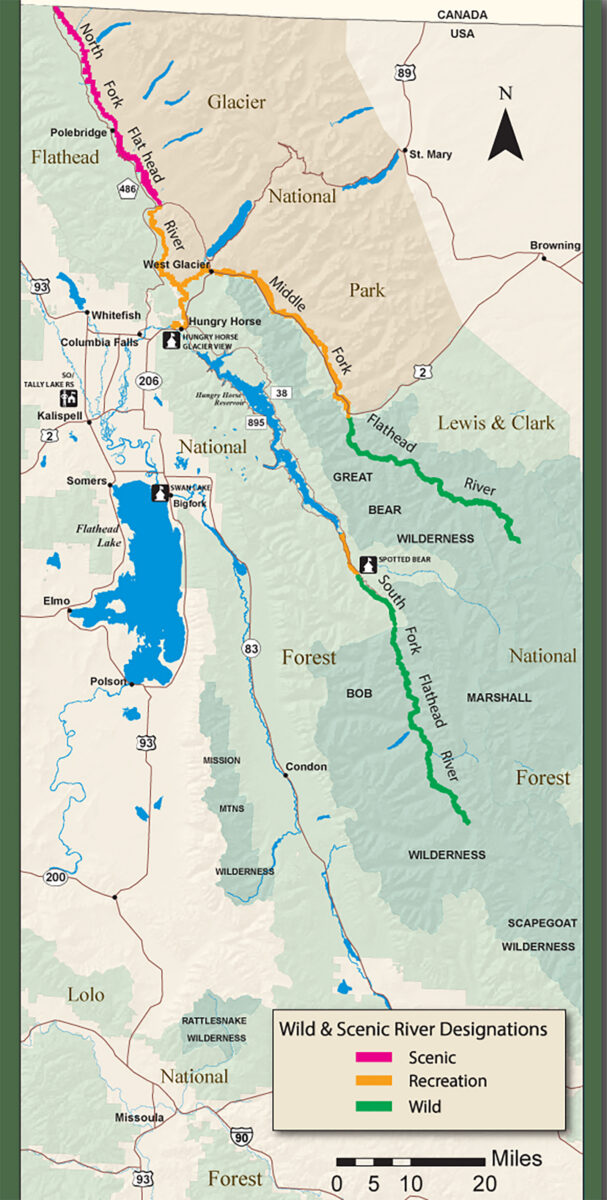

In 1976, Congress classified all 219 miles of the Flathead River’s three forks as wild and scenic under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, determining that the entire system meets the criteria because it is free-flowing, exhibits high water quality and features a suite of “Outstandingly Remarkable Values,” or ORVs. Under the designation, the three forks are protected from federally authorized dams and other major water resource projects that would compromise its free-flowing conditions, water quality and ORVs; however, the classification does not prohibit land-based activities, and still allows for management activities including timber harvests.

The three forks of the Flathead are currently managed under the 1980 Flathead River Management Plan. Since 2017, the Flathead National Forest and Glacier National Park have been updating the Comprehensive River Management Plan (CRMP) for a river system they cooperatively manage, while evaluating the significant increase of use (both on shore and by boat) and their obligation to protect the river system’s ORVs.

Unlike most other designated Wild and Scenic Rivers where one river falls under a single management jurisdiction, the Flathead River has three forks (North Fork, Middle Fork and South Fork) with different jurisdictions, even though the Flathead National Forest oversees most of the access sites; however, the Flathead National Forest shares management jurisdiction with Glacier National Park on the north and middle forks, portions of which are in recommended wilderness areas, while the South Fork and Middle Fork travel through two designated wilderness areas — the Great Bear and Bob Marshall Wilderness.

To parse out the diverse spectrum of wild and scenic values that define the three forks, the CRMP divides them into management units, assigning each segment its own set of desired conditions and classifications (wild, scenic and recreational) that “reflect management intent for different types of visitor experiences.”

“We have three forks, we have 219 miles of river that’s all wild and scenic, and there are 10 distinct segments. And among those segments, we have all the classifications of wild, we have scenic, we have recreational reaches, all managed for different desired conditions,” Davies said. “The opportunities for recreation are really diverse. You have remote areas and wilderness, you have incredible fishing opportunities, you have floating, you have whitewater, you have camping. There’s a whole diversity. So our plan, what we strive to do, is preserve some of the solitude in places where you expect solitude. There will be some segments that we’re managing for an uncrowded, quiet experience, and there’s other reaches we’re managing for freedom of access — that ability just to make a decision on the fly and go float after work without any restrictions or without any hoops to go through.”

Those management strategies will be determined by metrics such as capacity numbers and encounter standards, as well as thresholds and trigger points. The Flathead National Forest incorporated 20 years’ worth of encounter data into the plan, using it to set thresholds for “minimally acceptable conditions.” If the conditions fall below those standards, the agency would consider “corrective management actions to reverse the decline.”

“If we start to see a decline in conditions, we see more complaints, we start to have problems, we might have to institute some management actions,” Davies said. “Maybe we need more enforcement, maybe we need to write tickets. But at first, we’re going to be all about education.”

If it sounds as though many of the plans management directives have yet to be determined, Davies said it’s a feature, not a bug. The plan is designed to be adaptive and allow managers to be nimble in their implementation strategies. But the draft plan also sets forth several clear management actions.

Those include restrictions of motorized camping and parking on gravel bars; requirements that solid human waste be contained within 200 feet of the river’s edge; requirements of fire pans or fire blankets for all campfires below the high-water mark; an expansion of the “no stoppage” order for boats in the Goat Lick area (extending from the eddy below Staircase Rapid to one mile downriver of the Walton Goat Lick Overlook); and caps to outfitter and service days on sections of the Middle and North Forks.

As with most management plans for popular recreational river corridors, user capacity has been of primary interest to members of the public, with some critics of the proposed plan accusing managers of setting user capacities tand caps on commercial outfitters too high.

Joe Basirico, a former commercial outfitter who’s been floating the Flathead River system since before the Wild and Scenic Act was written, said he’s concerned about the degree to which the conditions of the three forks have deteriorated in the past 20 years. Specifically, he said commercial use has reached unsustainable levels, and the plan doesn’t provide any consequential guardrails.

“My concerns are with the capacity numbers. I started one of the first two commercial river companies in Glacier Park the year before the Flathead was declared a Wild and Scenic River,” Basirico said Feb. 17 during a public information meeting. “So when one talks about outstanding remarkable values I know what they are and they do not exist anymore, not anywhere near what they were back then.”

Outfitter and guide service days for fishing are currently capped by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at 4,002 on all segments of the Middle Fork and North Fork, a restriction that went into effect last year to protect struggling bull trout populations.

Outfitter and guides would continue to be permitted to operate on all segments where currently allowed based on their authorized user days. No additional river outfitter permits would be issued for floating and fishing opportunities.

But the draft CRMP would still allow up to 73,810 commercial user days for the new Middle Fork management unit from Cascadilla to West Glacier, and 45,980 on the section from West Glacier to Blankenship, for a combined total of 119,790 user days across the two management units with the highest concentration of commercial use.

“The new CRMP gives the commercial outfitters a 70% increase in their user days between Paola Creek and Blankenship,” Mike Burr, a Columbia Falls resident and longtime river runner. “That’s quite a bonus to the raft companies.”

According to Davies, the plan restricts the share of outfitter and guide service days on the North Fork’s recreational segment, where river use is increasing substantially, to a total of 8,712 service days. That cap is meant to ensure commercial use will not exceed 20% of the total user capacity estimate for the North Fork. The proposed authorized service days would include all current permitted service days, which account for approximately 641 service days, according to the plan.

The remainder of the service days allocated will be held in a priority use pool and will be available for use if biological and social resource conditions allow,” the draft plan states. “Outfitters may request an increase of service days up to 5% of their prior year actual use annually, if monitoring shows there are no impacts to social and biological resources, until the cap of 8,712 is met. The authorized official can restrict use to address resource conditions as warranted.”

Denny Gignoux, the owner of Glacier Guides and Montana Raft, said the volatility of floating season and tourism in northwest Montana often dictates whether his company approaches its permitted cap.

“We deal with gas prices, weather, wildfire, river flows, you name it,” Gignoux said. “It’s extremely difficult to predict and prepare for any given season, but our permit numbers are set. That doesn’t mean we’re going to hit that cap every year. And as a small business owner, I accept that there’s a lot that I can’t predict. But this notion that commercial outfitters are driving all the increased use on the river ignores the fact that our numbers are set, and the public’s numbers are not.”

To that end, the new CRMP does set capacity limits for public use.

The draft report sets the user capacity for the 46.6-mile section of the Middle Fork from its headwaters to Bear Creek, which is designated “wild,” at 150 people per day. It sets the 23-mile section from Bear Creek to Cascadilla (Management Unit 1) at 310 people per day, which is up from its estimated existing use of 235 people. The plan sets user capacity for the 16-mile section of the Middle Fork from Cascadilla to West Glacier (Management Unit 2) at 1,220 people per day, which is up from its estimated existing use of 947 people. The plan sets the capacity for the 15-mile section from West Glacier to the South Fork confluence (Management Unit 3) at 1,900 people, up from its estimated existing use of 476 people for a 300% increase.

On the North Fork, from the Canadian border down to Polebridge (Management Unit 1), the plan sets the user capacity at 310 people, up from the estimated existing use of 235 people; at 480 people from Polebridge to Camas Bridge (Management Unit 2), up from its estimated existing use of 185 people; and at 360 people from Camas Bridge to Blankenship, up from its existing use of 160. A user capacity of only 30 people would be prescribed on the South Fork section from the confluence of Youngs and Danaher creeks to Mid Creek in the Bob Marshall Wilderness.

For Basirico, the user capacities on the Middle Fork, especially, are already too high; allowing for a 300% increase makes it “impossible to think that isn’t degrading the outstanding remarkable values that we’re talking about.

“I need to reinforce that I am not speaking against commercial companies getting their fair share, and I’m not trying to start an argument,” Basirico said at Tuesday’s public meeting. “But I am saying your numbers are unreasonable to begin with on those two stretches of river. And I want to also compliment you on what you did as far as fire pans, [human waste containment] and camping on the river banks. those are three very good decisions that you made there.”

According to Davies, resource managers will continue to refine capacity limits moving forward, working with partners such as the Flathead Rivers Alliance to improve monitoring data.

“Capacity is not a calculated number based on scientific formulas. It really is a management determination,” Davies said. “We’re determining that if we reach that level of capacity, we’ll likely have impacts to the values, the outstandingly remarkable values, and what we’re ultimately trying to protect. That’s why we’re all here.”