WHITEFISH – At first blush, Richard Spencer doesn’t fit the conventions of a leading figure marching at the vanguard of a crusade to re-forge the iron face of white separatism and cast the movement into a more palatable mold, one that looks and acts a lot like him.

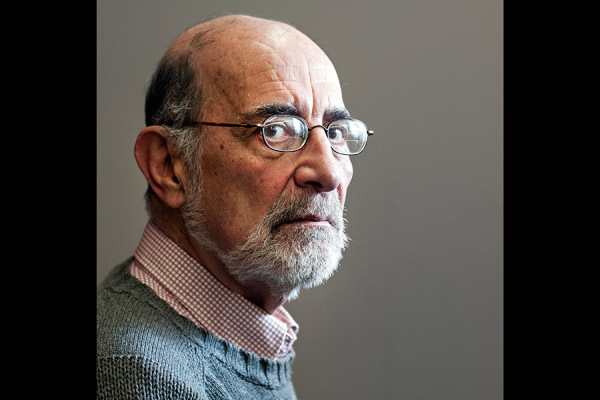

Spencer, 36, is clean-cut, well-heeled and pedigreed, and he shares the same suite of outdoors-themed interests that draws the majority of Whitefish’s residents to seek purchase in this mountain town. He is articulate, impeccably attired and he smiles easily.

He’s also at the fore of a movement to establish a white homeland in North America, an effort he believes would improve the genetic quality of the human population, which he says is being diminished by the rise of minority births in the United States.

Spencer migrated from the East Coast to Whitefish, he says, because of the allure of the mountain west – the quiet and the anonymity, the cycling and the skiing – and not, as some residents allege, to propagate the creation of a local white ethno-state, which, on a larger scale, he believes is fundamental to the human race’s success.

On its face, Spencer’s version of white nationalism is a more toothsome variant, a departure from what for generations has characterized the movement’s nebulous direction under the heavy hand of extremist hate groups, whose members have often resorted to violence, and whose legitimacy have increasingly been dismissed as vulgar fanaticism.

Conversely, a chance encounter with Spencer, a former quasi-mainstream, paleoconservative journalist originally from Texas, would not elicit a hateful string of racial epithets; he rejects the notion that he is promoting hatred and considers being labeled a “racist” a “slur.” More likely, he’d bring up the ideologies of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, or his opposition to the conflicts in the Middle East, or the snowpack on Big Mountain.

And until recently, nothing about Spencer’s local persona would reveal the fact that he occupies a prominent role in a global movement to reinvent white nationalism as a respectable class of intellectualism, which, in its cosmetically altered state, is increasingly appealing to the ranks of young, well-educated millennial-types who are disenchanted with the plodding traditions and tenets of neoconservatism and the stereotypes that pigeonhole the extremist, overtly racist right.

Under Spencer’s auspices, something less brash and unsightly has emerged, a nicely kempt, well-spoken figure, not a shadowy hatemonger, someone more difficult for the mainstream public to personify as the enemy.

A figure much like Richard Spencer.

But that reinvented image, local and national groups monitoring and protesting domestic hate groups say, is what makes his efforts so alarming.

For years, Spencer has worked in relative obscurity while promoting his views from various international platforms. But suddenly, Spencer is a household name in this small resort town, where he and his think-tank, the National Policy Institute, are headquartered, and he has become the subject of a proposed municipal ordinance to ban “hate-related” activities in Whitefish.

“Honestly, it’s easier to deal with a skinhead or someone whose hate is more overt, someone whose intolerance is uglier on the surface,” said Diane Smith, a Whitefish-based entrepreneur who is among the residents urging the Whitefish City Council to adopt a measure that would bar Spencer and the National Policy Institute (NPI) from conducting business here.

At a Nov. 17 council meeting, residents turned out in droves as more than 100 people packed the council chambers to decry Spencer’s residency and voice support for an anti-hate ordinance prohibiting groups like NPI from converging on the community.

The demonstration was organized by Love Lives Here, a Flathead Valley affiliate of the Montana Human Rights Network, and comes on the heels of renewed publicity for Spencer and NPI.

The not-for-profit NPI bills itself as “an independent think-tank and publishing firm dedicated to the heritage, identity, and future of European people in the United States and around the world,” and Spencer advocates “a White Ethno-State on the American continent.” Its Wikipedia page was recently amended to state that it is headquartered in Virginia, not Whitefish, though Spencer lives and works here during much of the year.

NPI’s publishing unit, Washington Publishing Summit, publishes “scientifically based” books like “Race Differences in Intelligence” and “The Perils of Diversity.” The group rejects calls for violence by extremists and encourages dialogue by organizing conferences around the world and inviting some of the most prominent thinkers in the fringe movement.

“Our goal is to form an intellectual community around European nationalism,” Spencer said.

His advocacy for white separatism creeps into conversation when pressed, but he just as easily articulates informed, mainstream arguments for conservation measures or healthy living. He says he’s never publicly advocated NPI’s views in the Flathead Valley, but rather works to promote them globally.

“We need a larger platform than Montana, and that platform is the Internet. What NPI does is not a Montana thing, to put it bluntly. I have never opined on NPI matters here, and on local issues I am more of a liberal tree hugger,” he said. “Living in New York or Washington can really be a drag, and it make sense for me personally because I love it here. I love skiing, hiking and biking. I love that you can walk out your front door and see the mountains. But I don’t want NPI to be associated with Montana. This is where I come to get away from it all.”

Spencer says he’s long held his radical views, but they began to evolve in earnest as an undergraduate at the University of Virginia and continued to shift to the right of the ideological spectrum in graduate school at the University of Chicago.

As an assistant editor at Pat Buchanan’s “The American Conservative” magazine, the radical-leaning shift continued as he left the publication to become executive editor of Taki’s Magazine (the publication of Buchanan’s co-founder in The American Conservative). He continued marching right, founding the webzine AlternativeRight before taking over as chairman of the National Policy Institute in 2010 and moving to Montana.

In April 2013, Spencer spoke at the American Renaissance conference, organized by a think tank of the same name, which promotes pseudo-scientific studies and research that purport to show the inferiority of blacks to whites.

In his speech, he advocated the creation of a white ethno-state on the North American continent, calling it an attainable goal.

“In the public imagination, ‘ethnic-cleansing’ has been associated with civil war and mass murder (understandably so). But this need not be the case,” he said.

In a recent conversation with the Beacon, the threads of Spencer’s ethnocentricism were slower to emerge during a lengthy discussion that ranged from the pitfalls of public education and social programs to Christopher Nolan’s space epic “Interstellar,” and from a ski-summit confrontation with a Washington, D.C. foreign policy adviser to the “biological realities of race” and the need for a white ethno-state.

His goal, he stressed, is to apply his philosophies globally, not in the Flathead Valley, and he balked at the recent public hearing in which attendees repeatedly labeled him a racist, accusing him of trying to realize NPI’s goals in the largely homogeneous community of Whitefish.

“Racist isn’t a descriptive word. It’s a pejorative word. It is the equivalent of saying, ‘I don’t like you.’ ‘Racist’ is just a slur word,” he said. “I think race is real, and I think race is important. And those two principles do not mean I want to harm someone or hate someone. But the notion that these people can be equal is not a scientific way of looking at it.”

The Southern Poverty Law Center has named Spencer and NPI one of the four leaders in the world of “academic racism.”

Spencer recently re-emerged in the national purview when he was arrested for 72 hours in Budapest, Hungary, and was subsequently banned from the country and most of the European Union for three years after trying to hold a conference expressing the group’s views.

In the wake of the renewed publicity, dozens of Whitefish residents banded together to urge council members to enact an ordinance barring hate-group activities in the community.

Organized by civil rights activist and local Rabbi Allen Secher, his wife, Ina Albert, and a host of other community advocates, the residents offered emotional testimony in an effort to “pass a no-hate ordinance so that hate organizations cannot do business in our town,” Albert said.

Brian Muldoon, a Whitefish attorney, said the proliferation of the views belonging to Spencer and NPI is dangerous.

“This isn’t about one individual, it is about a way of thinking that is despicable,” Muldoon said. “This community I believe is standing up strongly against the kinds of ideas that Richard Spencer and his ilk promotes … and it is time to deconstruct the ideas that are so insidious. It is time to take a very clear stance. An unambiguous one.”

At the end of the public testimony, which ran close to 90 minutes, Whitefish Mayor John Muhlfeld explained the procedural steps the council would have to take to consider such a measure, including advertising a hearing publicly, a planning board recommendation, and holding two council hearings for additional public comment.

“We will respond decisively, and I think we have multiple tools in our toolbox to consider this,” he said.

Similar anti-hate or anti-discrimination ordinances have been passed in other local communities, though infringing on First Amendment rights is a litigious issue, something that many of the speakers acknowledged.

Jan Metzmaker, former director of the Whitefish Convention and Visitors Bureau, which promotes tourism in the area, said she has known of Spencer’s presence for a couple of years, but thought giving him publicity would be counterproductive, harming the local economy and assigning him a level of notoriety that would buoy his public persona.

“We had this problem two years ago and I was shocked. But I didn’t want to bring more notoriety and press,” Metzmaker said. “Eventually you have to take a stand, but he’s allowed his freedom of speech. As abhorrent as his ideas are it will be difficult to find a place where he has his rights and we’re allowed ours. Still, I encourage the council to consider this issue.”

On Nov. 24, the Whitefish Convention and Visitors Bureau and the Whitefish Chamber of Commerce issued a joint statement supporting the passage of a “no-hate” ordinance, stating that they “adamantly disapprove of discrimination.”

At the end of the recent meeting’s public testimony, council member Richard Hildner offered his own emotional statement in support of a countermeasure to local “hate groups,” his voice choked with emotion as he fought back tears.

“Hate, racism, and bigotry are not community values in Whitefish and I promise you that I will do everything in my power to protect the city of Whitefish from racism, bigotry and prejudice,” Hildner said. “I want you to know that you have my pledge.”

Spencer’s presence is not the first time that a fringe group has found purchase in the Flathead Valley, or made headlines. Both Secher and Albert referred in their testimony to a spate of Holocaust-denial films shown publicly in the Flathead Valley in 2009 and 2010. The events were organized by well-known white supremacists seeking to transform the valley into a bastion for those who share white separatist ideologies.

The films prompted the formation of Love Lives Here, and residents attending the council meeting clutched posters bearing the group’s motto.

“I love this town. I adore it and I want to keep adoring it,” Secher told the council. “Let’s not even open the door to this guy.”

But the door has been opened, and Spencer doesn’t intend to leave, calling the notion of banning a person for his views ridiculous.

“I think the notion of banning me from a town is illegitimate,” Spencer said. “In any kind of activism, you want to personify an enemy. And I think that I have become that in some ways. I am kind of an easy target for them at the moment. But it seems more than a little bizarre that they are doing this. It seems that their end goal is totally misguided and I think it would be something they have a difficult time supporting morally and legally. Any time you talk about banning someone who is a law-abiding citizen, you are supporting what you oppose, which is fascism.”

Supporters of a measure, as well as leaders of Montana’s Human Rights Network, say his goals are obvious, and accuse him of soft-pedaling his intent. They claim he is trying to achieve a white ethno-state in the Flathead Valley, and that his and his mother’s construction of a building on Lupfer Avenue in Whitefish is proof of his plan to promote his agenda here.

NPI tax forms reveal a Whitefish P.O. Box, and state that its accomplishments include hosting a conference in Seattle on the matter of genetics, publishing a biannual journal on cultural matters and developing and maintaining a website “dedicated to original writing on social, cultural and scientific matters.”

But Spencer laughs at the notion that he’s trying to promote his agenda in Whitefish, describing his goals as loftier than a local ethno-state.

“I don’t really engage in activism and I’m not trying to take over a town. That is not what I do. I am more interested in connecting with people around the world and changing people’s minds,” he said. “I have never been interested in starting a movement here. That sounds a bit fantastical. Obviously I am trying to build a movement of people around the world and including the United States, but when I talk about an ethno-state I am not interested in maintaining a status quo. You can find an all-white suburb and say it is an ethno-state, but that is not what I am talking about. You could look at the Flathead Valley and call it an ethno-state because it’s 96 percent white. But the ethno-state I envision will arise as a future society.”

He continued: “What really makes European people special and our heritage special is that we reach for the stars and we believe in something higher than ourselves. I don’t want a society based on equality. I want a society that reaches for the stars. If you want to ask me about what am I thinking about at 2 a.m., that’s it. Reaching for the stars. In a way that is what an ethno-state is. It is an ideal. It is something to shoot for and strive for. It is not just about being in a place where you are amongst white people.”

He also dismissed the notion that he was drawn to the Flathead Valley in part because of the potential to find traction with like-minded white nationalists in the region, which has at times gained notoriety as an incubator for such groups; Spencer called those people extreme, and added that he is not a “white supremacist.”

“I am a radical. I am not an extremist. An extremist is someone who takes things too far. A radical is someone who wants to get to the root of something,” he said.

Spencer says he harbors no desire to advertise his views to his neighbors. “I don’t want to get in big disputes with anyone in Whitefish,” he says. “I would like this to be a place where I have a little bit of an anonymous status.”

But a recent report by The Daily Beast detailed a confrontation in early 2013 between Spencer and former John McCain advisor Randy Scheunemann, who owns a vacation home in Whitefish. At the time, both men were members of the private Big Mountain Club, and were riding a chairlift together when, upon realizing Scheunemann’s identity, Spencer began berating the man.

Scheunemann subsequently quit the Big Mountain Club when, he told reporters, it refused to oust Spencer from its ranks. Riley Polumbus, spokesperson for Whitefish Mountain Resort, said the claim that Scheunemann made a call for an ultimatum is untrue, and that both Scheunemann and Spencer resigned on their own accord.

According to a statement from the ski resort: “Whitefish Mountain Resort and the Big Mountain Club are not political organizations and will remain that way. That being the case, we won’t tolerate hate or inappropriate conduct. With regard to Richard Spencer, Randy Scheunemann and the Big Mountain Club, those individuals have submitted their resignations and thus neither will be a member of the Big Mountain Club for the 2014-15 season and beyond. Any suggestion that the Big Mountain Club has sided with a white supremacist in this matter is false, defamatory and contrary to what the Big Mountain Club and Whitefish Mountain Resort stand for.”

Spencer called the confrontation with Scheunemann and its aftermath unfortunate, and said he intends to avoid Scheunemann in the community. He also called the confrontation an aberration from his normal behavior.

Diane Smith, the local entrepreneur, encouraged the Whitefish City Council to think outside the box and use its power and intellect to craft a solution that distances NPI and Spencer from the community, even if that means challenging legal precedent. She pointed to the council meeting’s turnout and the textured political spectrum of its attendees as evidence of the strong support for such a measure.

“Sunlight really is the best deterrent, and this needs to be something the community discusses,” she said. “We are all here, from the right, the left and the center, banding together through a sense of justice and sensibility. You have other tools in your toolbox. We prohibit porn shops, jaywalking and marijuana head shops, and we can regulate hate. Some issues are worth being sued over.”