Fifty years ago, at the height of the civil rights protests, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. asked the Central Conference of American Rabbis to visit St. Augustine, Florida, to assist in efforts to end segregation.

Sixteen reform rabbis and a Jewish administrator answered King’s entreaty, knowing the civil rights leader had been arrested a week earlier at the Monson Motor Lodge, his life threatened repeatedly.

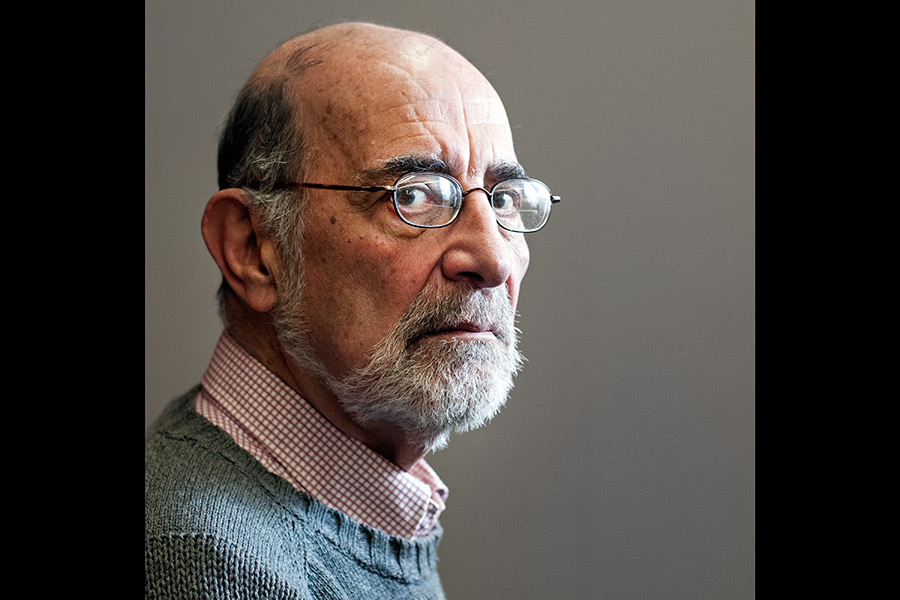

Among them was Allen Secher, a Whitefish rabbi at the Bet Harim Jewish community.

On June 17, 1964, Secher, then 29, marched at the vanguard of a group of 100 demonstrators, walking through segregated neighborhoods and enduring a torrent of racial slurs; in the wake of death threats and the shooting of a demonstrator, he also feared for his life.

“You’ll believe me when I tell you it was the scariest two hours of my life. When we reached the white neighborhoods there were groups waiting for us. They didn’t attack us, but we were taunted,” he said.

The demonstrators walked en masse to an historic slave market, braving mobs of segregationists wielding bricks and broken bottles. At the old slave market site, they held a prayer service and sang freedom songs before returning home.

“I remember it clearly, but the next day I witnessed one of the most shocking scenes I have ever seen. It has become indelible,” Secher, 79, said recently as he prepares to return to St. Augustine to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the historic occasion.

On June 18, 1964, Secher was among 16 rabbis arrested at the highly segregated Monson Motor Lodge in the largest mass arrest of rabbis in U.S. history. Moments before the arrest, Secher recalls looking on in horror as the motel owner, James Brock, poured hydrochloric acid into a whites-only swimming pool to drive out several black demonstrators, who were attempting to desegregate the motel pool by staging a wade-in along with two white hotel guests.

The little known event is considered a major turning point for the civil rights movement, and cleared the way for the passage of the Civil Rights Act two weeks later, at a time when the flagging movement desperately needed momentum.

Secher and the other rabbis spent three days in jail. It wasn’t the first time he’d been arrested while assisting King’s efforts.

“Historically, the Jewish community has always been leaders in the civil rights movement,” said Secher, who became involved with the movement in 1962, when he was arrested in Albany, Georgia, during one of King’s Freedom Rides protesting the segregation of a library.

Following that arrest, Secher spent a week in jail, and said King and the Freedom Riders inspired him to take part in the movement because of the gross injustices dealt to Jews, and also due to the hatred he experienced directly.

“My affiliation with the movement was motivated by the Holocaust, but personally I have additional motivation,” he said. “I grew up in very anti-Semitic town in Pennsylvania, where my head was busted open with a rock and I was called ‘Jew bastard.’”

He continued: “I was turned away from a Catholic hospital with an appendicitis attack and told there were no doctors available. I wasn’t allowed to be part of the high school golf team because the country club was restricted. I had girls’ parents saying that I can’t go to the dance with Barbara. I was the only Jew in my high school class.”

Perhaps the experience even led Secher to the clergy.

“It could be that my psychological response to this was, ‘OK, you’re going to call me a Jew, then I’m going to become super Jew,’” he said.

He did not hesitate to travel to St. Augustine for the protests at King’s behest.

Secher was in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on June 16, 1964, attending a convention along with 500 other rabbis when King telegrammed the group and, the following day, he made the trip to St. Augustine. After he arrived, Secher and the other demonstrators received their instructions from King, and spent hours learning about passive resistance and what to do if they were attacked.

“We were told that there had been a shooting by a segregationist who climbed up into a tree,” he said. “I was paired with a young black girl at the front of the line. It was absolutely terrifying.”

The next day, the rabbis accompanied a group of black activists to two restaurants and the swimming pool at the Monson Motor Lodge, where Secher witnessed one of the iconic images of St. Augustine’ civil rights struggles as Brock, the hotel manager, dumped a gallon of muriatic acid into the pool in which the demonstrators swam.

“He didn’t realize that the acid would dilute itself, and neither did the kids, and that’s the amazing courage of it,” he said. “The kids weren’t going to budge. And we witnessed all of this. It literally sucked the breath out of you.”

Armed with cattle prods, police segregated the black and white demonstrators and arrested many of them. According to an FBI report, the 16 rabbis, the swimmers, the two leaders of the march and nine other demonstrators were taken to jail to join the more than 200 people arrested earlier in sit-ins.

Secher said after he was arrested, an officer made him and other rabbis pose for a photo. Moments later, he witnessed another officer shove a cattle prod up a white female demonstrator’s skirt.

“It stands as the most gruesome thing I have ever witnessed,” Secher said of the mistreatment.

While jailed for three days, Secher and the rabbis wrote a letter to the St. Augustine community, explaining why they chose to participate in the demonstrations.

“We came to St. Augustine mainly because we could not stay away. We could not say no to Martin Luther King, whom we always respected and admired … We came as Jews who remember the millions of faceless people who stood quietly, watching the smoke rise from Hitler’s crematoria. We came because we know that, second only to silence, the greatest danger to man is loss of faith in man’s capacity to act.”

Secher is one of six rabbis who will return to St. Augustine to commemorate their role in achieving civil rights.

In addition to Secher, the rabbis returning for the June 17–18 event are Israel Dresner, Daniel Fogel, Jerrold Goldstein, Richard Levy and Hanan “Clyde” T. Sills.

The rabbis will read the famous “Why We Went” letter in the St. Augustine Visitor’s Information Center.

“Maybe we did have a role in ending segregation. It would be nice to think we did,” Secher said. “But we’re celebrating because it’s a reminder that we still have tons of work to do. There is still work, but would I do it again? You betcha.”