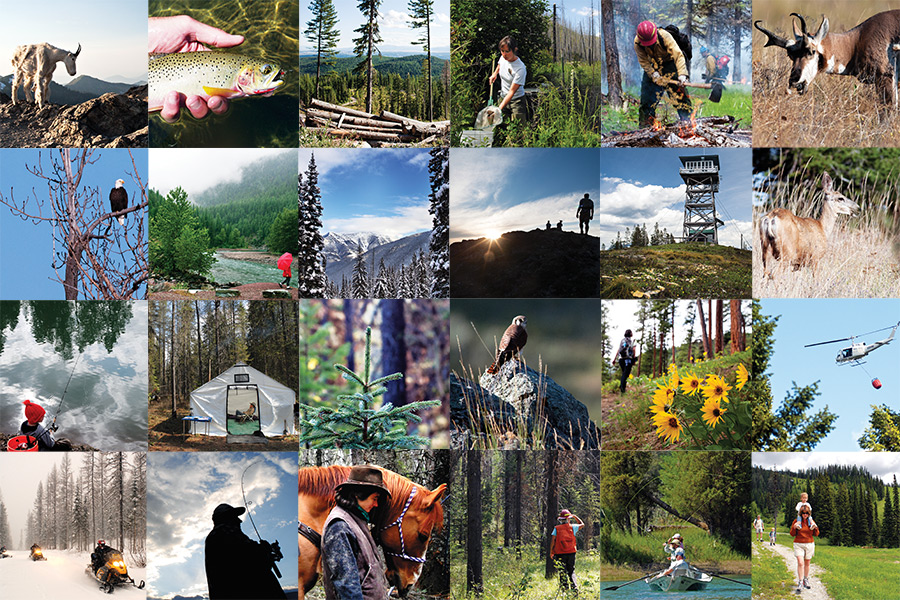

Hiking, camping and fishing. Harvesting timber. Sheltering a diverse collection of wildlife and fish species amid scenic rivers and wild forests.

The Flathead National Forest — spanning 2.4 million acres, making it the 10th largest national forest in the U.S. — plays a significant role in the cultural and ecological landscape.

Seeking “the greatest good” for the Flathead’s wild interior over the next two decades, the U.S. Forest Service is proposing a historic makeover of its broad management strategy.

After nearly two years of public meetings and analysis, the agency on March 5 released its proposed revision of the Flathead National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan, or forest plan. The agency’s current plan has not been revised since 1986 and this latest edition will guide management decisions for 15 years after it is formally adopted.

The public scoping period for the expansive 499-page document is 60 days. Both the plan and an interactive map detailing its various proposals are available online at http://www.fs.usda.gov/goto/flathead/fpr. A public meeting is scheduled for 5:30 p.m., March 17 in Kalispell at the Forest Service office at 650 Wolfpack Way. Other meetings will be held in Eureka, Seeley Lake and Missoula.

“This represents an important milestone for us, to start this next stage of the collaborative process,” project leader and forest planner Joe Krueger said.

“This is really the public’s plan for how we’re going to manage the forest, and we’ve been tooling and retooling standards, guidelines and objectives based upon a lot of the feedback we’ve already got.”

There are several significant aspects in the agency’s revised plan that could change recreation and timber harvest opportunities and alter the management strategy for wildlife and land resources.

In concurrence with the plan’s unveiling, the Flathead National Forest also released a conservation strategy for grizzly bears in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem. An amendment detailing how grizzly bears will be managed in the future is being added to the Flathead forest plan, as well as forest plans for the Helena, Kootenai, Lewis and Clark and Lolo national forests. The conservation strategy is required under the Endangered Species Act before a population can be delisted. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has said the population of grizzly bears in the NCDE has increased to a point where it is no longer threatened.

For the forest plan revision, agency officials did adopt recommendations of the Whitefish Range Partnership, a coalition of three dozen local interest groups, including timber executives and wilderness and recreation advocates, that began a multi-year planning effort aimed at reaching community consensus on the management of the Whitefish Range, which is part of the Flathead National Forest near Whitefish and Columbia Falls.

Krueger said the agency considered the recommendations of the partnership valuable and adopted proposals that were considered worthy, although some were tweaked.

The revised plan recommends 188,000 acres of new protected wilderness, including the Jewel Basin, the Tuchuck-Whale area and additional sections in the Mission, Bob Marshall and Great Bear wildernesses. The total acreage is a few thousand acres less than the Whitefish Range Partnership recommended. To avoid “de facto wilderness” concerns, the agency would allow existing uses in these areas as long as they don’t degrade the wilderness character and the land’s potential to be designated, according to officials. Congress would need to authorize the formal wilderness designation.

The forest plan identifies 22 rivers and streams — stretching a total of 276 miles — that are eligible for protection under the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Those streams include the Danaher from the headwaters to Youngs Creek; Big Salmon from Lena Lake to the South Fork Flathead River; and Spotted Bear, from the headwater to the South Fork Flathead River.

“We looked at a whole suite of rivers on the forest and we looked at them for outstanding and remarkable values related to botanical, geological, recreational and scenic qualities,” Krueger said.

The wild and scenic designation means the agency would continue to manage the rivers to protect them as valuable resources, Krueger said. Congress would need to authorize the formal designation.

Nine potential bird and wildlife “species of conservation concern” are identified, as well as two potential aquatic species and 13 possible botanical species. To identify species of concern, agency officials looked at the state’s ranking system, which multiple agencies use to determine the status of wildlife populations that could be at risk of being threatened or endangered.

The agency has identified 637,419 acres of land that are suitable for timber production, an increase from its previous target amount. The agency identified areas near Tally Lake as having the highest amount of suitable timber, while other areas that are considered vital grizzly bear habitat were less emphasized, Krueger said.

The proposed plan would call for 28 million board feet of timber harvested each year, which is based on the current agency budget allotment, Krueger said.

“What we heard from industry is they want a number they can rely upon, instead of constant fluctuation,” Krueger said.

Responding to a growing interest in recreation opportunities, the agency has identified so-called front country areas, including around Lakeside, Bigfork, Whitefish and Hungry Horse Reservoir, where “untapped recreation potential” exists, according to Krueger.

“The public has really told us to provide front country recreation opportunities that have easy access. We’ve looked hard at this issue,” he said, listing sites such as Cedar Flats, Hungry Horse Reservoir and Crane Mountain, a popular mountain biking area, as examples.

The plan also proposes changes to areas that are considered suitable for over-snow vehicles, such as snowmobiles, by requesting to open access in the lower end of Big Creek from McGinnis Creek to the North Fork Road, south to Canyon Creek, while decreasing the same amount of open acreage in the upper end of Sullivan Creek, Slide Creek and Tin Creek.

Krueger said a primary goal of the new overall plan is to maintain “flexibility” and “to put in important safeguards to maintain a diverse landscape and ensure diversity of wildlife species in the face of a changing landscape as a result of disturbances, fires, disease, insects and climate change.”

As with most things related to the federal agency’s management of forestlands, the proposed revision is certain to garner scrutiny among environmentalists and others.

Keith Hammer, chair and founder of the Swan View Coalition, an environmental group based in the Swan, has been a vocal critic of the Forest Service and the Whitefish Range Partnership. He claimed the Whitefish partnership gained unfair influence during the agency’s forest plan revision process.

Hammer, who formed the Swan View Coalition during the contentious period when the 1986 forest plan was being crafted, said this new plan appears to take a step backwards instead of making positive progress for fish, wildlife and habitat. He raised concerns about the new recreation proposals, which could harm natural research areas and fragile wildlife habitat, while also trying to log more timber without analyzing the impacts to threatened and endangered species.

“This is playing politics over the scientific and biological needs of wildlife. That’s often what this comes down to,” Hammer said.

Krueger disagreed with Hammer’s assessments. He said the Whitefish Range Partnership provided healthy dialogue among interest groups that have not historically seen eye to eye and broke through decades of gridlock.

“I was very impressed with the diversity of that group,” Krueger said. “It was a collaborative in every sense of the word and I disagree that it was out of balance.”

Michael Jamison of the National Parks Conservation Association, who helped organize the Whitefish Range Partnership, said the coalition appreciated the Forest Service considering its ideas. Members of the group were still reviewing the forest plan revision earlier this week and planned to meet in the coming weeks to discuss the various proposals in the document.

“It’s difficult to know the details yet but from what I’ve seen so far it’s encouraging,” Jamison said. “We certainly never had any delusions that we would hand them our ideas and they would accept them wholesale. That was never our plan. Our plan was to be part of a process where our ideas hopefully were good ideas because they were arrived at with a lot of different perspectives working together in the same room.”

Krueger also disagreed with Hammer’s claim that the agency is risking sound science by proposing new recreation opportunities or areas of suitable timber.

“I would argue that this (plan revision) has the strongest protections for wildlife that you can find anywhere, and it’s reflected by the way we have been managing wildlife here,” Krueger said.

“That’s why we have so many native species here. We have the best habitat and the best managed forest you will find.”

»»» Click here for several documents detailing previous revised forest plans and analyses.

Flathead National Forest Plan Revision

A Few Key Proposed Actions

Source: Flathead National Forest

— Emphasize “front country” recreation and increase opportunities around Lakeside, Bigfork, Whitefish and Hungry Horse.

— Recommend 188,000 acres for inclusion into the National Wilderness Preservation System, including the Jewel Basin, the Tuchuck-Whale areas and additions to the Mission Mountain, Great Bear and Bob Marshall wilderness areas.

— Identify areas that are suitable for over-snow vehicle uses. Increase suitable acres open to snowmobiles in the lower end of Big Creek from McGinnis Creek to North Fork Road, south to Canyon Creek. Decrease equivalent amount of acres open to over-snow vehicles in the upper end of Sullivan Creek, Slide Creek and Tin Creek. Proposed changes would need to undergo site-specific analysis in order to be implemented.

— Continue management standards for lynx habitat but with clarification and consideration of long-term desired conditions at a landscape level.

— Identify 22 rivers and streams eligible for inclusion into the National Wild and Scenic River System: Aeneas, Big Salmon, Clack Creek, Danaher, Elk, Gateway, Glacier, Graves, LeBeau, Lion, Little Salmon, Logan, Spotted Bear, Schafer, Strawberry, Lower Swan River, Whale, White River, Nokio, Yakinikak, Trail and Youngs.

— Recommend nine potential wildlife species of conservation concern: common loon, fisher, flammulated owl, harlequin duck, western big-eared bat, northern bog lemming, black swift, veery, Clark’s nutcracker.

— Provide for timber output of approximately 28 million board feet annually on 637,419 acres of “suitable timber base.” In comparison, the 2006 proposed revision plan identified 529,000 acres of “suitable timber base” and the 1986 plan identified 707,000 acres.

— Continue management standards for riparian habitat conservation areas, but with modifications that provide more flexibility to treat vegetation within conservation areas to achieve desired conditions.

— Ensure habitat protections specific to grizzly bears that are consistent on key forest lands within the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem, by incorporating the relevant habitat management direction rom the grizzly bear conservation strategy.

Clarification: The Flathead National Forest’s 2006 forest plan proposed revision initially identified 328,328 acres suitable for timber production. After the public scoping period, the agency modified the plan and increased that figure to 529,000 acres, which was cited above. According to Krueger, the agency identified additional access to existing roads and areas where the agency wanted to conduct “vegetation treatment.”

Correction: The black-backed woodpecker is not being listed as a species of conservation concern, as was previously stated. The black-backed woodpecker is being recommended as a species of public interest for viewing.