Last month, Bike Walk Montana launched the inaugural statewide commuter challenge in an effort to encourage active transportation like bicycle commuting, and at the Beacon a handful of employees took part in the month-long competition, logging miles between our homes that pepper the Flathead Valley and our office in downtown Kalispell.

A week after the competition wrapped up, I was still pedaling my Raleigh single-speed to work from Whitefish most mornings, cruising a 20-mile route I cobbled together along a mix of rolling asphalt-and-gravel back roads, which are appealing as much for their dearth of traffic as for the valley views they afford.

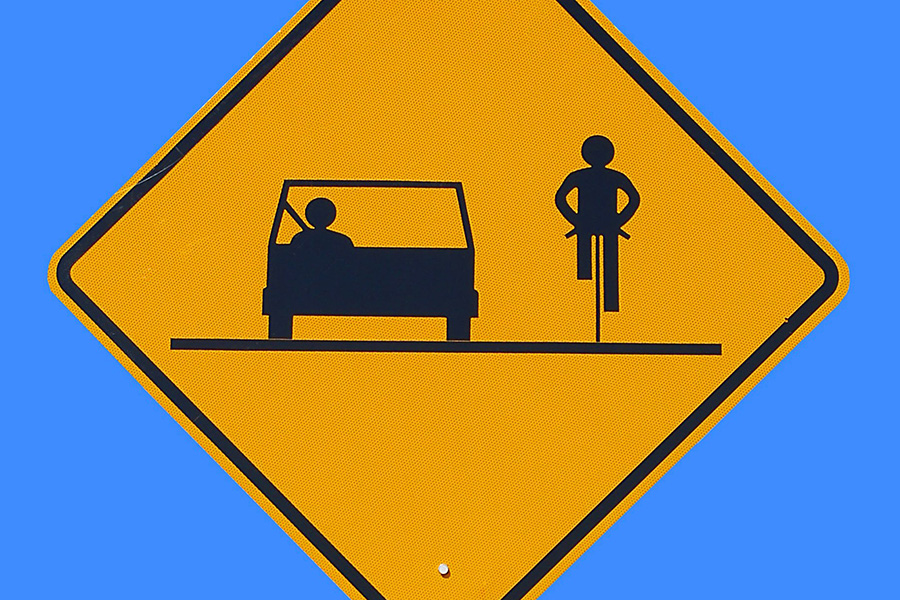

Sharing the road has its risks, and one element that unites all bicyclists is a fear of being hit by a car, a risk tempered by vigilance and safety practices but impossible to dispatch from the ever-present stock of cycling challenges. Except along roadways that incorporate separate bicycle-pedestrian facilities, cyclists need to share the same roads as motorists, simple as that.

And while many drivers take care to give cyclists a wide berth and respect our standing as roadway users, others don’t. In the sprawling Flathead Valley, many of us work and live in separate communities that are not connected by bike paths, and bike commuters are faced with a decision to pedal on busy highways or navigate a network of narrow back roads.

Biking is also an eco-friendly, healthy and fun alternative to commuting by car, and in that respect the benefits to me outweigh the risks.

But on the morning of June 8, I was forced to reevaluate that risk-benefit relationship when, exactly two blocks from the Flathead Beacon office’s front door, a motorist ran a stop sign and broadsided me with her Jeep.

She stopped, for which I’m grateful, but in those hyper-charged moments between spotting her oncoming rig, absorbing its 5,000 pounds of cast aluminum and sailing through the air like a ragdoll, a level of trepidation and vulnerability crept through me with a vigor I hadn’t experienced in a long time.

A potent mix of shock and adrenaline seized me as I struggled to wrest off my toe straps, untangle myself from the crumpled frame and stand up. The Reynolds tubing of my Raleigh was bent in such a way that I couldn’t fathom how my legs hadn’t been snapped. I didn’t hit my head or break any bones, and aside from some road rash and bruises, a banged up knee and a monumental degree of soreness, I am physically fine.

The bike was totaled, and while the accident stirred up an upsetting sense of my own mortality and left me feeling a bit indignant, the most lasting emotion has been an overriding sense of fear.

That feeling was reinforced when I recently interviewed Melinda Barnes, executive director of Bike Walk Montana, and learned more about the strides needed to promote safe cycling in the state.

In addition to her work as a tireless advocate for better bicycling in Montana, including promoting a host of proposed measures during the 2015 Legislative Session, I identified with Barnes because she was also recently hit by a car while riding her bike to work.

Barnes was struck from behind by an elderly driver and suffered a concussion. She was wearing a helmet, as well as a front-and-rear lighting system to make her more visible in the morning light. And while she recouped her medical expenses and the value of her bicycle, she said the experience left her shaken up.

“It’s terrifying and it just really reinforced my belief that we need separate facilities,” she said. “We need separated bike lanes, better education and more people out there riding to increase awareness.”

As a state, Montana consistently ranks among the least bicycle friendly in the country. In 2015, the League of American Bicyclists ranked Montana 46th in the nation for bike-ability, panning its lack of infrastructure and funding, its outmoded legislation and enforcement statutes.

The previous year, Montana ranked 49th.

Last session, the only bicycle-safety bill to fully pass the Legislature was House Bill 280, which cleans up antiquated and ambiguous language in the statutes explaining how people are allowed to ride bicycles on the roadways.

Barnes said because there are so few bicycle lanes across the state, bicyclists almost always share the roads with motorists, and it’s essential that they’re able to do so safely.

Still, another bill that would have required motorists to provide a minimum distance of four feet when passing a cyclist died in committee, and the state lacks a “vulnerable-user” statute that would make drivers more accountable if they hit a cyclist (the motorist who hit Barnes was fined $90).

“We have a long way to go as a state,” Barnes said.

For more information on Bike Walk Montana, visit www.bikewalkmontana.org.