Fading Away

As Montanans live longer, more families are dealing with the devastation of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease while research and medical facilities try to keep up

By Molly Priddy

Each morning, Glenn Mueller starts his day with Helen.

Well, that’s not entirely accurate – at 97, Mueller’s day starts at 5 a.m., when he wakes, showers, and dresses, all to be ready to see her by 8 a.m. Things that used to take no time at all seem to take all his time now, like putting on shoes and socks or getting his bearings immediately after standing.

It’s OK that he’s a bit slower now; Helen always waits for him.

Once he’s ready, he heads to the lobby of Buffalo Hill Terrace with his walker, and sets out for the building across the street. He used to only need a cane, but a fall last winter – hurting nothing but dignity, he says – spooked him.

But Glenn is quick with the walker, and makes brisk work of the path between his home and hers. Arriving at her building, Glenn uses his keycard to unlock the door, parks his walker in the hallway, and removes his ball cap.

And there she is, his wife of nearly 63 years, sitting in the middle of the comfortable TV room, dressed in pink and holding a pink teddy bear.

“Good morning, beautiful,” Mueller says as he leans over to kiss her forehead.

By the time he’s stood back up, he’s weeping, and then apologizing for the tears.

Helen, 91, registers that he’s there, but seems more interested in the visitors he’s brought with him. They don’t converse anymore, and he doesn’t know what she would have to say, what’s left of her memories.

The dementia hit a little over three years ago, and the result has been devastating, leaving Helen largely immobile and unable to feed herself. As her husband who, other than combatting the slow physical decline of being nearly 100, is in good health, Glenn feeds her yogurt and hot chocolate in the mornings, and otherwise watches as she slips further away. She’s in hospice care along with the other care she receives from the staff at the Immanuel Lutheran Communities in Kalispell.

Breakfast is a battle of wills, with Glenn almost begging Helen to open her mouth so he can feed her the yogurt.

“Helen. Helen, look at me please. Helen. Open your mouth. Please Helen. Please.”

Tears fall from Glenn’s face as he stoops with the spoon, cajoling the woman who brilliantly cooked for and fed their family of three daughters, and the eventual grandchildren.

They have had a wonderful life together, Glenn says, spending 50 years in Libby before moving here once her mind started its decline. She was one of the smartest people he’s known, he says multiple times.

“That’s the one smart thing I did in my life, was marrying that lady,” Glenn says.

Death is an inevitability we face as soon as our lives begin. What’s less certain is everything else around death, the how and the why and the when of it all. But in all its forms, one of the cruelest ways to lose someone is when it happens and yet their body remains.

Most everyone has a family member or knows a friend who has struggled with dementia; the Alzheimer’s Association estimated that one person is diagnosed with the disease every 67 seconds.

The emotional toll of dementia is painful enough for the families and friends of those affected, but there are other more-concrete costs associated as well.

Dementia is the general term for a “decline in mental ability severe enough to interfere with daily life,” according to the Alzheimer’s Association. The association’s namesake disease, Alzheimer’s, is the most common form.

More than 5 million Americans are afflicted, with 27,000 Montanans expected to be diagnosed in the next decade. Caregivers spend millions of hours caring for loved ones with Alzheimer’s, with a total of about $668 million worth of unpaid care.

If better treatment for the disease is not available, the Alzheimer’s Association estimated that by 2050, America will be spending $560 billion on Alzheimer’s treatment through Medicaid and Medicare, compared to the $153 billion already projected for 2015.

And while money is a huge concern, the real fear lies in knowing as the local community continues to live longer, more neighbors, friends, and family members will have to deal with dementia.

The draft State Plan on Aging for 2016 through 2019, which is still out for public comment through the Department of Public Health and Human Services, lists Montana’s 65-and-older population as 16.1 percent of the total population in 2014, already a 2 percent increase over 2010, and the state is consistently ranked as one of the oldest in the nation.

Kalispell and the rest of Flathead County are also favorites when it comes to rankings for the best places in the country to retire, and along with the natural beauty, the burgeoning health care industry here is part of the reason why.

With a rapidly aging population comes the health needs of such a group, and dementia is a major factor. A statewide committee, the Montana Alzheimer’s Dementia Work Group, is collecting information on the care needs of communities across the wide expanse of Big Sky Country.

Part of the problem, according to Holly Garcia, the study coordinator at the Center for Translational Research at Billings Clinic and coordinator of the dementia work group, is that Montana is largely made up of rural and frontier counties.

The study, which should be released in time to back up legislative action for the 2017 session, has only produced preliminary data so far, Garcia said, but what the work group has found backs up the idea that more aging Montanans means more dementia and Alzheimer’s, and more resources needed to help.

This means more memory-care facilities in more counties. All too often, Garcia noted, families must uproot their affected loved one to a new town for these services.

“Ideally, we’d like to keep people in their home communities as much as we can,” she said.

•

Helen and Glenn met in 1950, in Malta. He was a young man from Lewistown working for the U.S. Forest Service, and she was the home economics teacher, who had moved about 85 miles from her home in Nashua.

Their lives intersected at a bake sale, whether Glenn was aware of it at the time or not. Helen, in a letter she wrote to Glenn on his 80th birthday, said she spotted him first.

As the home ec teacher, she was also the advisor of the Future Homemakers of America club, which was hosting a bake sale fundraiser at the Montana Power Company offices.

“During the morning a young man walked past our sale into the manager’s office. I commented to one of the girls that he looked like a ‘good family man’ and that she try to sell him something on his way out. He got away tho! It wasn’t until after Glenn and I were married and I was hanging up a yellow and black plaid jacket that I realized he was ‘that man.’ My first impression was certainly accurate and I’m glad I made ‘a sale’ even tho the FHA girls didn’t,” she wrote.

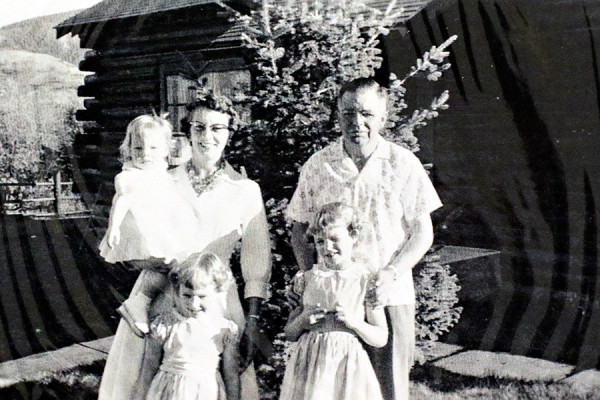

They moved to Libby, where they would settle and raise their three daughters. Glenn remembers a happy life, working for the Forest Service and fostering a love for the outdoors within his girls.

Helen was active in the community and her church, and was an avid quilter, doing all the stitching by hand. She was also very bright and a great cook, Glenn said, and a wonderful mother and wife.

As they aged, the couple began wintering in Arizona, and would for 20 years before Helen’s problems arose. He didn’t see the dementia at first, Glenn says, but the signs were there. Bouts of forgetfulness turned serious, like when Helen was not able to find the grocery store located just a block away.

“She went to get some food and couldn’t find it,” Glenn says. “And then she couldn’t find a friend’s apartment that was next door to ours. So I knew that was our last winter in Arizona.”

A doctor in Libby diagnosed Helen with dementia, and Glenn knew it was time to move to Kalispell, despite having planned on living out their days in Libby. But their small town didn’t have the care facilities Helen needed, and so they moved three years ago.

When they first arrived and Helen was placed in a separate building, she was confused about the separation from her husband. She was also using a walker, and could zip about.

She doesn’t ask about why she lives away from Glenn anymore, and about two months into her stay she transitioned to a wheelchair.

Now that he is so familiar with dementia, Glenn says he sees it everywhere.

“Many of the ladies that I’ve talked to (at the Terrace) have gone through what I’m going through now,” he says.

And even through his teary eyes and pain-etched face, Glenn is relentlessly positive about the life they shared together. It was good, he says.

“Why she ever married me I’m not sure,” Glenn says. “I’m glad she did. She was a sharp lady, she really was.”

In Kalispell, the Immanuel Lutheran Communities serve as one of the largest and most comprehensive memory care facilities in the area. But more services are needed, Carla Wilton, executive director at the assisted living center Buffalo Hills Terrace, said.

“Our plans are to build assisted-living memory care facilities,” Wilton said. “As the numbers are exploding over the next years, there’s just going to be an ongoing increased need for both community programs that assist caregivers at home, as well as residential placement.”

Home caregivers experience huge drains in emotional, financial, physical, and mental resources. Wilton, along with Flathead County Agency on Aging and A Plus Health Care, started a community group focused on addressing the needs of caregivers.

The idea is to assess how dementia-friendly Flathead County is, Wilton said, and then identify improvement areas.

Last week, the group, made up of caregivers and the people they care for, went on an outing to Lone Pine State Park. Another idea is to have a café for caregivers and their charges, where unexpected outbursts or other behaviors are OK.

“It gets embarrassing to eat or go out for coffee when you’re never sure what they’re going to say,” Wilton said. “There’s some stigma attached.”

Ideally, the county would become one where public service employees like the police are better able to identify dementia-related behaviors, so the caregivers and those suffering the dementia can leave what usually ends up being isolation at home and participate in the community once more.

“Physically, oftentimes they’re super healthy, so they don’t need to be locked in a house, but that isolation sometimes happens because there’s not a safe place to be,” Wilton said. “And, if it’s not working at home anymore, we want to provide a safe residential place.”

Fundraising for the project continues, and Wilton expects groundbreaking on the new memory-care facility by spring 2016.

On Oct. 24, Immanuel Lutheran will host a private screening of “I’ll Be Me,” a documentary following famed musician Glen Campbell and his family through his journey with Alzheimer’s.

Following the documentary screening, Campbell’s daughter, Ashley Campbell, will perform music.

Proceeds raised from the October screening will support the building of the Memory Garden at the new facility, and benefit the Memory Care Fund at the Immanuel Lutheran Communities.

•

Helen is asleep before Glenn can give her any of the hot chocolate. She spends most of her time asleep, he says, which is probably a blessing. Another blessing is that she still seems to recognize her daughters and grandchildren.

As for him, Glenn jokes that Helen likely thinks an old man is trying to feed her, but while he wheedles the spoon into her mouth, she looks at him – really looks, not just idly gazing the way she does at most everything else – her eyes wide and clear, trusting and gentle.

Most of what made Helen Helen may have slipped away, but her love for Glenn remains, as easy to see as the sun in the sky on a bluebird day.

She’s Helen, his Helen.