Still in the Hunt

At 95, Montana’s first hunter education instructor continues to pass on a beloved tradition to new generations and teach the ethics and safety for chasing big game

By Dillon Tabish

A big bull elk with antlers like tree branches and a golden hide that shines in the daylight is mounted in the cozy living room, its distinguished presence taking up an entire corner of the home.

Some hunters can spend a lifetime in the field and never witness an animal this grand. It took Pat McVay 89 years and a “long walk.”

The six-point bull now resides near the edge of the forest east of Kalispell, keeping McVay company in the longtime home of one of Montana’s great, visionary sportsmen.

It’s autumn, and McVay has this year’s tags ready along with “Maggie,” his beloved 300 H & H Magnum Model 70 rifle.

“She’s pretty faithful,” he says, clutching the rustic firearm that was made in 1938.

It’s almost time to resume the general hunting season, a Montana tradition dating back 120 years, one that is inextricably tied to the state’s identity. One of the first bedrock laws in the Montana territory in 1895 established regulations for hunting in an effort to protect big game populations for future generations.

Hunting is a journey that tends to follow five stages. Many hunters begin with an interest in marksmanship. As they learn the basic skills and tenants of the sport, they embark into the wild in the age-old pursuit of big game. With success, they graduate to a more selective stage, searching for that monumental triumph. After achieving success, they can become inspired to follow the sport to its challenging extremes in search of greater lessons and growth, such as bow hunting. And finally, after years of experiencing the thrill firsthand, seasoned hunters often arrive at what is called the philosopher stage, a point characterized by the desire to pass on a lifetime of lessons and knowledge to a new generation.

At 95, McVay is still going in the field each fall for hunting trips with family and friends, but more notably he is still relishing the final phase as a true mentor.

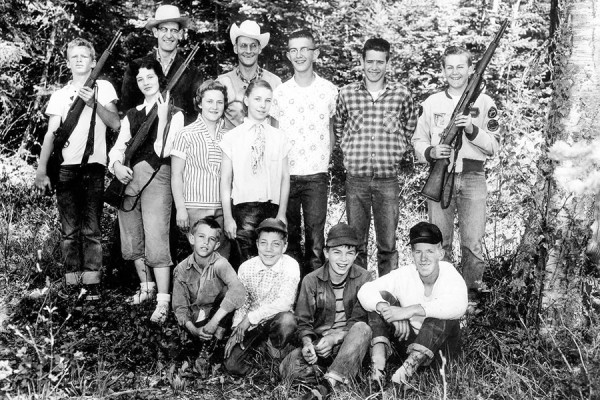

McVay holds the distinction of being the first official hunter education instructor in Montana. Every year since 1957, when Montana adopted a new law requiring all hunters under 18 to take a state-sanctioned educational course, he has volunteered to lead classes. He has taught three generations of hunters in the Flathead Valley the proper steps it takes to be a hunter, helping them undergo a rite of passage before they embark on personal journeys that often span lifetimes.

“There’s a lot of stuff in hunter safety, not only the four rules of gun safety, but about the outdoors, what’s out there and how to accept it,” he says.

McVay is a lifelong hunter who has chased game everywhere, from the plains of eastern Montana to the rugged Bob Marshall Wilderness, where he has logged over 7,000 miles.

You could say he has a few tips worth sharing.

A student must be at least 11 years old to become certified in hunter education. The courses are free and open to anyone. The courses often feature kids and adults, especially parents who want to accompany their child in the field. The classes vary in length depending on the instructor. McVay’s span five nights with a field day at the end. He holds the courses at his home in a basement that could double as a sportsmen museum, and spends time going over firearms safety, wildlife identification, the ethics of fair chase, laws and regulations and survival techniques for the outdoors.

“I’ve watched a couple hunting shows, and they climb up a tree and sit up there. And then they shoot a deer,” McVay says, shaking his head. “That’s not hunting. You got to get out there and give a fair chase.”

On the field day, he sets up a course in his backyard where students must properly carry firearms through fences and over obstacles. They also learn to shoot from various stances, taking into account all the surroundings.

“I feel that every kid has a natural curiosity about guns and if you can satisfy that in a safe and reasonable, careful way, then you’ve got that kid going down the right path,” McVay says.

Yet in the end, shooting ends up playing a minor role in hunting.

“Everything that you can see and enjoy, and everything out there — when you pull the trigger, the fun is over and the work starts,” he says. “All your pleasure is before that.”

Like all instructors across Montana, McVay teaches these classes for free.

“One of my mottos has been for many years that a minute was never lost when it was spent with a child,” he says. “And I just thoroughly enjoy watching the kids and seeing them react and learn. And then one of the big perks is when they come up grinning like a watered mule and hand me a picture of their first deer. I’ve got a few of them around the house. It just makes it all worthwhile.”

An estimated 1,800 instructors volunteer their time annually to train about 10,000 students each year in FWP’s hunter and bow hunter education programs.

McVay is among a small fraternity of hunters who have over 50 years experience. There are nine men in the entire state with plaques from Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks recognizing their volunteer service for over 50 years, including Bob Larsson in St. Ignatius, who has also been teaching hunter education since the first year, in 1957. Leonard Howke of Whitefish has taught classes since 1965.

“They have had such a big influence on our heritage of hunting in Montana,” says Ron Aasheim, spokesperson with FWP. “They have influenced generations of hunters in Montana.”

Hollister Pat McVay was born in 1920 in Oklahoma to a farming family. They moved to a homestead south of Great Falls, where McVay was raised.

“My granddad gave me a .22-caliber rifle when I was 6 years old. I was in first grade. My brother had one, too, and he was a few years older,” McVay said. “We were on our own out there on the ranch south of Great Falls. He just told me be damn careful. That’s the only advice we got.”

McVay developed a passion for adventuring in the mountains and for shooting. He started with gophers on the ranch but it evolved into a desire to chase deer and elk. Harvesting a deer was also an important source of food for families struggling through the Great Depression.

As a young man McVay trained with the Air Force before serving in the Army from 1942-1946. He earned a job at the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington, but in 1952, he transferred to Hungry Horse Dam. It was there that he became involved with a firearm safety program for young shooters through the National Rifle Association’s (NRA) Junior Rifle Program.

By the 1950s, the popularity of hunting was spiking across the U.S., but with that came an increasing number of accidents, primarily involving guns. There were no formal training programs and most hunters learned from rugged experience, similar to how McVay did. Some states began implementing hunter education courses, and that caught McVay’s attention.

He studied the programs and what other states were doing with gun safety and sent a letter to the NRA asking for materials he could use for a homemade course. The materials arrived in the mail, and in the mid-1950s he was holding a firearm and hunting safety class in Hungry Horse for young kids in the Junior Rifle Program. McVay’s close friend, Mel Ruder, the owner of the Hungry Horse News, detailed McVay’s upstart program in news stories and used it as an example of something that could benefit statewide hunters. By 1957, the Montana Legislature passed a law establishing the hunter education program.

“Mel Ruder called me at 10 p.m. from Helena, and said, ‘Pat, it passed.’ The next day I mailed all the stuff to Fish and Game,” he says.

On record with FWP, Pat McVay is listed as the first official instructor, starting Jan. 1, 1957.

“Pat was a visionary,” says John Fraley, spokesperson and education supervisor for FWP’s Region One. “He saw the importance of this over half a century ago. When I think of Pat, I think of Aldo Leopold.”

Leopold was a famed ecologist and conservationist credited with developing the modern environmental ethics through his writings and advocacy. He established the early science of wildlife management that still guides agencies across the U.S., including FWP.

“When you talk about Pat, you do hear the word ‘legend’ batted around a lot by the kids and parents,” Fraley says. “We’re privileged to have Montana’s first hunter education instructor in the Flathead.”

The way McVay describes it, the privilege has been all his own. Long before he shot the trophy elk of a lifetime that now hangs in his home, he had achieved rewards far greater than any single animal. Thank-you letters fill his home, from mothers and fathers who are grateful for passing on a love of the outdoors to their children. One man even showed up to McVay’s home a couple years ago and re-introduced himself. He was a student of McVay’s almost 40 years earlier and simply wanted to stop by and share his appreciation.

McVay says his best memories are afield with family and friends. Just last fall, he helped set up an annual hunting trip for its 50th year near Malta. Friends, family and nearby ranchers all came together one night inside a wall tent with fiddles, harmonicas and stories to share.

“Couldn’t have been a better bunch of people,” he says.

After 95 years, all the memories are hard to keep straight. All McVay needs to do is gaze at the big bull elk in his living room, and the stories start coming to life, adventures of a legendary lifetime.