After four years thrashing out the details of a proposed management plan for the Flathead National Forest, a blueprint has emerged to guide a wide range of uses on 2.4 million acres of ecologically and economically productive land for the next decade or more.

Land managers hope the final product will strike an accord that balances wilderness, timber production, recreation, wildlife conservation, and other interests, but said divisions will undoubtedly prompt objections from user groups in the next two months.

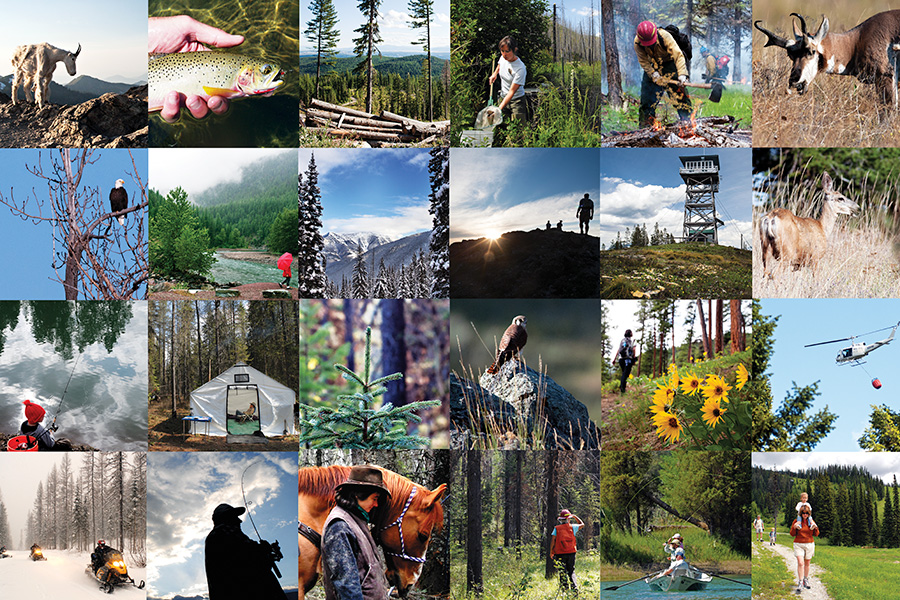

Still, although he acknowledges that land-use disputes will continue as long as public land exists, Flathead National Forest Supervisor Chip Weber said the proposed plan considered the needs of all stakeholders — tree huggers and tree cutters, hikers, horsemen, mountain bikers, snowmobilers, cabin owners, boaters, anglers, grizzlies, and nearly everyone else with a stake in the management of public lands on the Flathead National Forest.

“This plan does the job for the environment and it does the job for the people,” Weber said. “It’s a comprehensive plan to manage the Flathead National Forest, which is 2.4 million acres of what I would consider highly cherished lands and one of the best-functioning and intact ecosystems in the world.”

The sheer size of the Flathead National Forest ranks it as the 10th largest national forest in the U.S., but the significance of its role in the region’s cultural, economic and ecological landscape is difficult to quantify, such is its vast importance.

In a nod to U.S. Forest Service’s founder, Gifford Pinchot, the plan seeks “the greatest good” for the Flathead’s wild interior over the next decade or more, and proposes a historic makeover of its broad management strategy, which hasn’t been updated since 1986.

After four years of public meetings and analysis, including more than 33,000 comments on the draft environmental impact statement, the agency on Dec. 14 released its final environmental impact statement (EIS) and record of decision for the Flathead National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan, or forest plan. The latest edition is designed to guide management decisions for 10-15 years after it is formally adopted.

The release of the forest plan initiates a 60-day objection period, which applies to stakeholder groups, agencies and individuals who have already filed objections and raised concerns.

Weber said any sweeping changes to the plan are unlikely, but said the agency will determine that once it has received and reviewed the final round of input. The agency will have until mid-May to review the objections and respond.

In crafting an update of its so-called forest plan, the Forest Service is recommending dramatic changes to recreation and timber harvest opportunities, as well as the management strategy for wildlife and land resources.

In concurrence with the plan’s unveiling, the Flathead National Forest also released a conservation strategy for grizzly bears in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem. An amendment detailing how grizzly bears will be managed in the future is being added to the Flathead forest plan, as well as forest plans for the Helena, Kootenai, Lewis and Clark and Lolo national forests. The conservation strategy is required under the Endangered Species Act before a population can be delisted. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has said the population of grizzly bears in the NCDE has increased to a point where it is no longer threatened.

For the forest plan revision, agency officials did adopt recommendations of the Whitefish Range Partnership, a coalition of three dozen local interest groups, including timber executives and wilderness and recreation advocates, that began a multi-year planning effort aimed at reaching community consensus on the management of the Whitefish Range, which is part of the Flathead National Forest near Whitefish and Columbia Falls.

In the last decade, trends in forest management have tended more toward stakeholder engagement and community-based collaboration to provide input on the management of national forests nationwide. The 2012 National Forest Management Planning Rule codifies the trend with a requirement that national forests provide an opportunity for citizens to collaborate both with other stakeholders and forest managers on future management of national forests.

The Flathead National Forest is one of the first forests to implement the new rules.

Weber said the agency considered the group’s recommendations valuable, and while they weren’t adopted wholesale, they helped inform the proposed management plan, as did input from a broad range of interests and cooperative agencies.

“I believe this plan is a very balanced approach to providing for values that are on the table for what is currently and will continue to be a healthy functioning ecosystem,” Weber said. “We have some of the best of the best in terms of wildlife habitat, fish habitat, recreation, and timber resources, and this plan allows us to maintain those qualities and make improvements.”

Among its many proposals, the forest plan recommends 190,000 acres of land for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System, including the Jewel Basin, the Tuchuck-Whale areas and additions to the Mission Mountain, Great Bear and Bob Marshall wilderness areas.

It provides for timber output of approximately 28 million board feet annually on 637,419 acres of “suitable timber base.” In comparison, the 2006 proposed revision plan identified 529,000 acres of “suitable timber base” and the 1986 plan identified 707,000 acres.

It identifies 22 rivers and streams — stretching a total of 276 miles — that are eligible for protection under the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Those streams include the Danaher from the headwaters to Youngs Creek; Big Salmon from Lena Lake to the South Fork Flathead River; and Spotted Bear, from the headwater to the South Fork Flathead River.

“We looked at a whole suite of rivers on the forest, and we looked at them for outstanding and remarkable values related to botanical, geological, recreational and scenic qualities,” Joe Krueger, forest planner and project leader, said.

The wild and scenic designation means the agency would continue to manage the rivers to protect them as valuable resources, Krueger said. Congress would need to authorize the formal designation.

Nine potential bird and wildlife “species of conservation concern” are identified, as well as two potential aquatic species and 13 possible botanical species.

To identify species of concern, agency officials looked at the state’s ranking system, which multiple agencies use to determine the status of wildlife populations that could be at risk of being threatened or endangered.

Among the nearly 640,000 acres of land identified as suitable for timber production, the agency named areas near Tally Lake as having the highest amount of suitable timber, while other areas that are considered vital grizzly bear habitat were less emphasized, Krueger said.

The proposed plan would call for 28 million board feet of timber harvested each year, which is based on the current agency budget allotment, Krueger said.

“What we heard from industry is they want a number they can rely upon, instead of constant fluctuation,” Krueger said.

Responding to a growing interest in recreation opportunities, the agency has identified so-called front-country areas, including around Lakeside, Bigfork, Whitefish and Hungry Horse Reservoir, where “untapped recreation potential” exists, according to Krueger.

“The public has really told us to provide front-country recreation opportunities that have easy access. We’ve looked hard at this issue,” he said, listing sites such as Cedar Flats, Hungry Horse Reservoir and Crane Mountain, a popular mountain-biking area, as examples.

The plan also proposes changes to areas that are considered suitable for over-snow vehicles, such as snowmobiles, by requesting to open access in the lower end of Big Creek from McGinnis Creek to the North Fork Road, south to Canyon Creek, while decreasing the same amount of open acreage in the upper end of Sullivan Creek, Slide Creek and Tin Creek.

Paul McKenzie, land and resource manager for F.H. Stoltze Land and Lumber Co. in Columbia Falls and a participant in the Whitefish Range Partnership, said he hasn’t finished reviewing the sprawling plan, which totals about 3,000 pages. McKenzie said he hopes the final proposal captures most of the elements the group agreed upon during the collaborative process.

“I hope they listened to us,” McKenzie said. “There were a lot of people who spent a lot of time providing good substantive input to the Forest Service for how to craft this plan in a way that benefits a wide range of interests.”

Two conservation groups critical of the forest plan are the Swan View Coalition and Friends of the Wild Swan, both of which said the proposal rolls back protections for threatened and endangered species like bull trout and grizzly bears.

Keith Hammer, chair and founder of the Swan View Coalition, formed the group during the contentious period when the 1986 forest plan was being crafted. He said the new plan does less for fish, wildlife and habitat, taking a step backwards in terms of conservation.

“The revised plan is an irresponsible rollback in essential protections and reflects the political haste to remove Endangered Species Act protections from the grizzly bear,” Hammer said.