“Haven’t seen a real fire or smoke yet,” Edward Abbey wrote in the Numa Ridge Lookout logbook on July 12, 1975. “One craves a little excitement around this joint.”

Abbey, then 48, was at his day job in Glacier National Park. Working as an aspiring novelist in the 1970s didn’t pay all the bills, so Abbey spent a good portion of his life employed by the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service, working first as a ranger and then as a seasonal fire lookout.

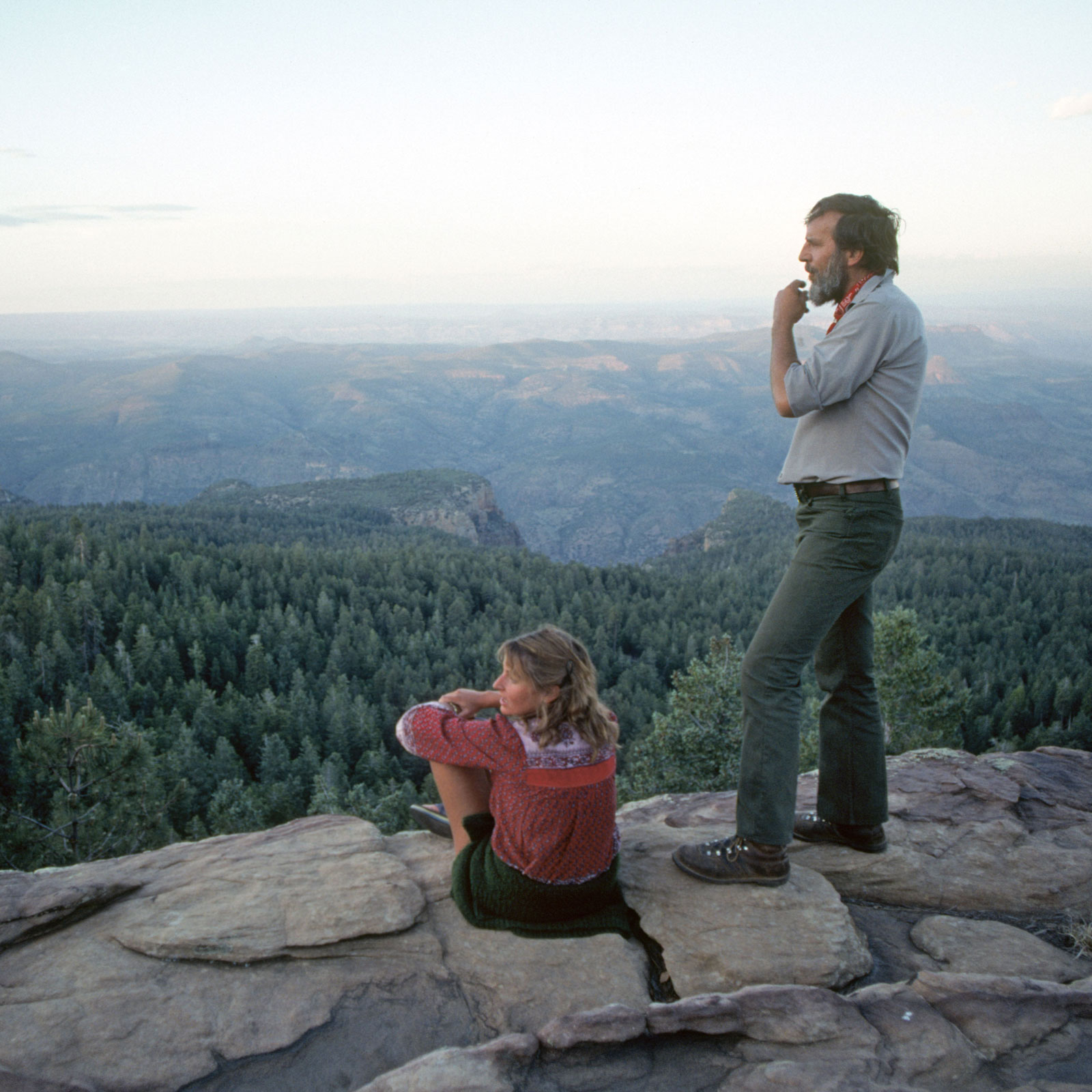

In 1975, his seasonal stints as a lookout took him to Numa Ridge in the northwestern corner of Glacier National Park.

Like a lot of people, Abbey didn’t always love his day job.

Abbey repeatedly attributed his distaste to a few culprits in the lookout’s official logbook: the presence of hikers and other visitors (“No hikers today. Good.”), the aforementioned lack of excitement due to an unusually wet summer in the park and the obnoxious prevalence of mosquitoes.

Many great works of literature have been written, or inspired, by summers spent manning fire lookouts across America, scanning the horizon day in and day out in search of smoke.

Jack Kerouac, the beatnik best known for writing “On the Road,” included accounts of his job as a fire lookout on Desolation Peak in the North Cascades in several of his books, and Norman Maclean, of “A River Runs Through It” fame, wrote about his time as a lookout in the Bitterroot National Forest.

Abbey, the ecological philosopher behind such works as “Desert Solitaire” and “The Monkey Wrench Gang,” spent the better part of a decade’s worth of summers as a lookout in Arizona, California and Montana.

Abbey’s accounts of those experiences are documented in both his nonfiction and fiction. His novel “Black Sun” featured a protagonist who served as a fire lookout, and many of his essays offer glimpses into his time on the job in Arizona.

Less well known is his summer in Glacier Park.

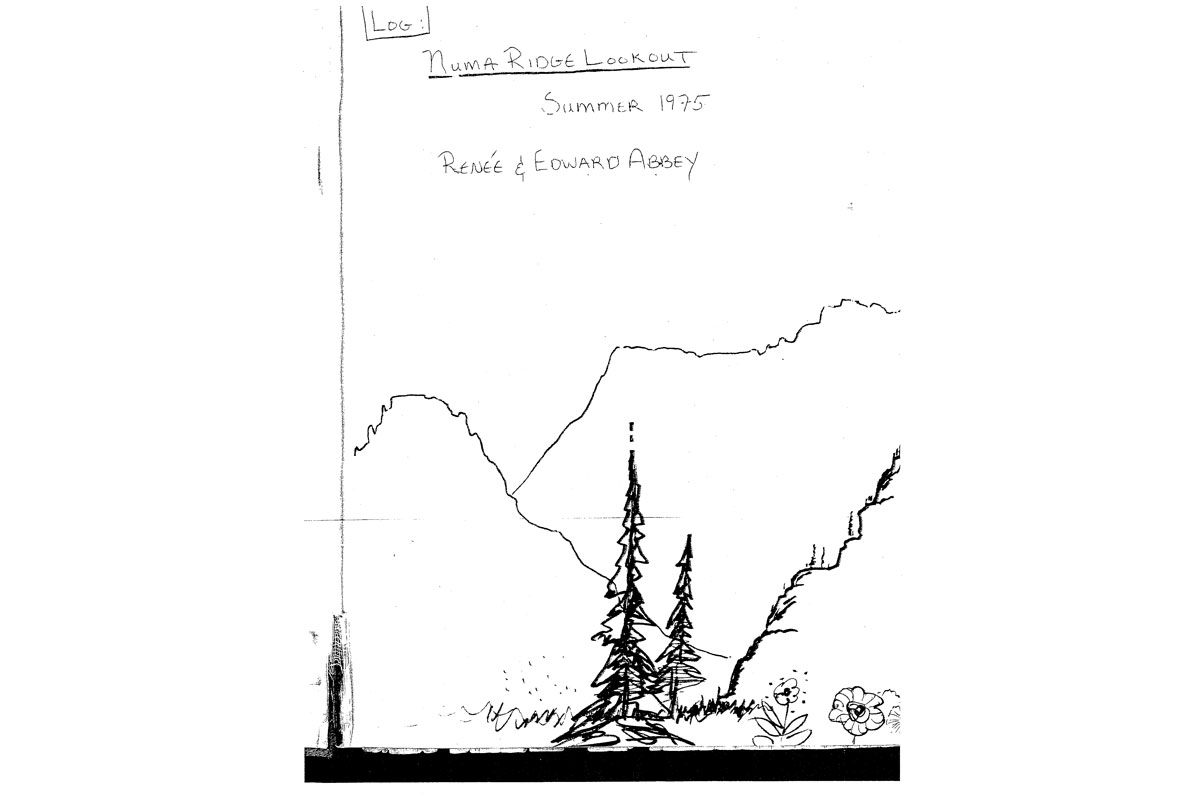

Abbey published just one short collection of journal entries from his summer in Glacier, in a chapter of his book “The Journey Home” entitled “Fire Lookout: Numa Ridge.”

The 20-odd pages of his notes are detailed, and written in the meandering metaphysical style that characterizes much of Abbey’s writing.

“We’ve been here ten days before I overcome initial inertia sufficient to begin this record,” Abbey wrote in “The Journey Home.” “And keeping a record is one of the things the Park Service is paying us to do up here. The other, of course, it to keep our eyeballs peeled, alert for smoke.”

Abbey and his fourth wife, Renee Downing, arrived at Numa Ridge on July 2, 1975, to spend the summer earning a “generous wage” of $3.25 an hour to watch for any hint of smoke or flame in the peaks surrounding Numa Ridge, which overlooks Bowman Lake and North Fork Flathead River vistas.

The account of his Glacier summer includes discussions of the books brought to the lookout (seven volumes of Proust and Robert Burton’s “Anatomy of Melancholy”), how he feels that he is cheating the solitary confinement of lookout life by bringing along his wife and many philosophical musings on the world.

“This is a remote place indeed, far from the center of the world, far away from all that’s going on,” Abbey wrote. “Or is it? Who says so? Wherever two human beings are alive, together, and happy, there is the center of the world.”

In contrast, entries from the logbook, which is held in the Glacier Park archives, offers a rawer, more intimate portrayal of life at the lookout.

Wed. July 16: “Have whipped wife in five games straight at chess now. She won’t play anymore. Have to think of something else.”

Tues. July 22: “Wife beats me two games of chess … Now she’s getting more interested.”

The prevalence, absence and return of the mosquitoes is well documented in the Numa logbook. In contrast, Abbey’s published journal spends a lot of time “thinking about GRIZ,” although he never manages to track down Glacier’s most iconic fauna that summer.

His published account of July 21 waxes poetic about being an uninvited guest in the homeland of the grizzly bear, but the official logbook for that day instead quotes a Ralph Hodgson poem.

“The days rush by with alarming speed. Why this headlong descent into oblivion? Must be some way to slow down that process of decay: need a higher tedium quotient in our daily round.

Time you ol gypsy man/

will you not stay/

put up ur caravan/

just for one day?

Etc.”

In truth, from the chore lists to wildflower identifications, many of Abbey’s words written in the logbook ring true nearly 50 years later, and not just his gripes about mosquitoes.

An entry from August 7 sums up an environmentally focused curmudgeon’s view of Glacier National Park with what is still a complaint from visitors today:

“Too many people; Not enough Grizz [sic].”

The working fire season of 1975 was cut short due to the wet weather and early arrival of winter — Abbey reported two inches of snow on August 24 — with a departure date moved up to September 5 and then August 28.

The last entry is from August 28, just before Abbey packed down the mountain.

“Departure day & naturally it’s raining! Ah well, what the hell, it was a damn sweet summer.”