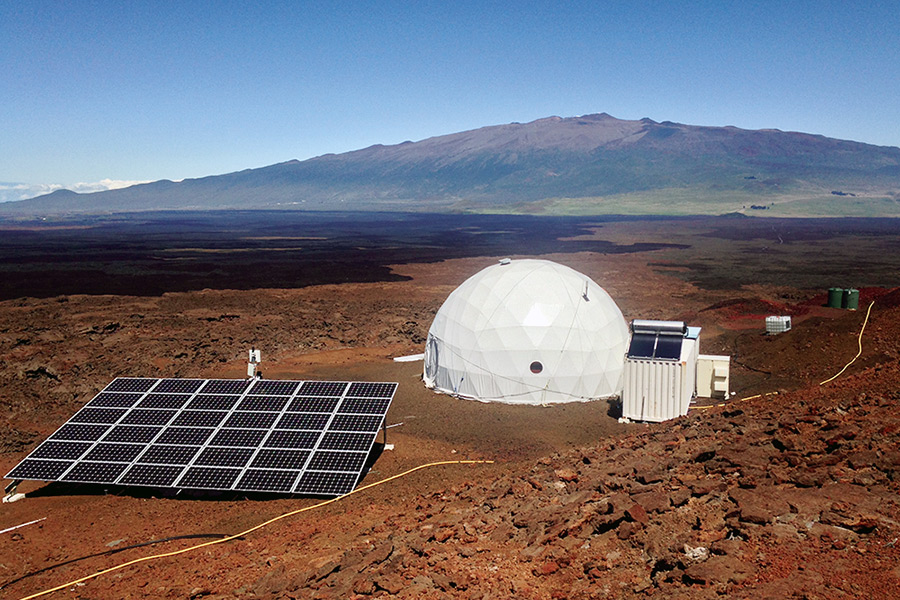

The email’s subject line read “Hello from Mars.” The email from 26-year-old Whitefish native Carmel Johnston was not from the red planet, exactly, but it was from the 36-foot-wide dome perched on Hawaii’s Mauna Loa, the largest subaerial volcano on Earth, which is the closest thing to Mars that exists on this planet.

Johnston is the commander of the fourth Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) Mars Mission crew. She and five other crewmembers are almost three months into a 365-day mission at the dome.

HI-SEAS, a NASA program, aims to understand how human factors like social, interpersonal, and cognitive dynamics contribute to an astronaut crew’s performance over time. Months spent isolated in a confined space can do weird things to the human psyche, and NASA researchers hope observations of life in the dome, designed as an analog habitat for human spaceflight to Mars, will provide insights for selecting and training the best crew for a future Mars voyage.

“We want to find out everything that can go wrong so that it doesn’t go wrong on the way to Mars,” said Johnston, who has a Master of Science in Land Resources and Environmental Sciences from Montana State University.

Though Johnston is a scientist, she’s also the test subject in this study. She doesn’t play a part in data collection or analysis, but much of her day is spent completing projects designed by HI-SEAS scientists back in civilization.

Johnston’s scientific specialty is soil and she is conducting some research of her own while sequestered. Though she can’t create an oxygen-deficient Martian atmosphere, she is simulating experiments with Mauna Loa soil, which is quite similar to Martian regolith.

The dome is an imperfect likeness of Mars in many other ways.

“Actually being on Mars will be something that no one will know until they are there,” Johnston said. “If you are 34 million miles and a seven-month long space flight away from home, you will feel a lot different than knowing that you are on a volcano in Hawaii. We don’t have the one-third gravity of Mars or the low O2 atmosphere to really give you the fear of getting a tear in your space suit.”

Still, Johnston and her crew “work under a lot of the same mental conditions that the Martians will live with,” like 20-minute delayed communication with Mission Support, daily scheduled tasks, and limited resources. She’ll have to work with the same five people every day for a year without pause. She also won’t be able to ski this winter or hike next summer. Her HI-SEAS bio reads, “My favorite things include being outside (yes it’s weird that I’m spending a year in a dome).”

But, Johnston says, she “wanted to be here so that I could do my part in the advancement of space exploration.” And in some ways, the dome is “actually just like being at home. My family has always done things the ‘hard’ way. Made food from scratch, fixed something if it was broken instead of buying a new one, made presents from the heart instead of from the wallet.”

Maybe there’s something special about how Montanans are raised – the crew’s architect, Tristan Bassingthwaighte, grew up just two hours away in Missoula. He stumbled across HI-SEAS while researching habitats in extreme environments for his Masters degree, and is now designing a Mars base as part of his doctoral project.

Though Bassingthwaighte, like most of the crew, wants to go to space, Johnston says she’s “happy here on Earth. There is more than a lifetime worth of stuff for me to do on Earth, so I’m keeping my feet planted here.”

As a teenager at Whitefish High School, she wanted to study how rivers change and participated in the Flathead River Educational Effort for Focused Learning in our Watershed, where she learned about water quality, stream health, and the influence of humans on water quality in the Flathead Valley.

While completing her masters, she studied carbon dynamics in permafrost soils in Alaska. Then, after finishing her thesis, she traveled to New Zealand and Australia to study the impact of climate change on livestock management. This past summer, she worked as a soil scientist in Glacier National Park for the Natural Resources Conservation Services.

“In high school, I wanted to be a fluvial geomorphologist,” Johnston said, “But now I really just want to learn about everything I can. Everything in our world is interconnected. So why not learn about all of it?”